http://dx.doi.org/10.24016/2019.v5n1.160

ARTÍCULOS ORIGINALES

Are Believers Happier than Atheists? Well-being Measures in a Sample of Atheists and Believers in Puerto Rico

¿Realmente son los creyentes más felices que los ateos? Medidas de Bienestar en una Muestra de Ateos y Creyentes en Puerto Rico

Juan Aníbal González-Rivera 1 *, Adam Rosario-Rodríguez 2, Eduardo L. Rodríguez-Ramos 3, Idania Hernández-Gato 2, Lourdes M. Torres-Báez 4

1 Ponce Health Sciences University, San Juan University Center, Puerto Rico.

2 Universidad Carlos Albizu, San Juan, Puerto Rico.

3 Universidad de Puerto Rico, Recinto de Bayamón, Puerto Rico.

4 Universidad de Puerto Rico, Recinto de Ciencias Médicas, Puerto Rico.

* Correspondencia: 500 West Main Suite 215, Bayamón, P.R 00961. Tel.: 787-315-6034. Email: jagonzalez@psm.edu

Recibido: 27 de septiembre de 2018

Revisado: 31 de noviembre de 2018

Aceptado: 03 de diciembre de 2018

Publicado Online: 01 de enero de 2019

CITARLO COMO:

González-Rivera, J. A., Rosario-Rodríguez, A., Rodríguez-Ramos, E., Hernández-Gato, I., & Torres-Báez, L. M. (2019). Are Believers Happier than Atheists? Well-being Measures in a Sample of Atheists and Believers in Puerto Rico. Interacciones, 5(1), 51-59. http://dx.doi.org/10.24016/2019.v5n1.160

ABSTRACT

Currently, not much has been written about the empirical psychological well-being of the atheist community in Puerto Rico and Latin America. The objective of the present study is to analyze if there are statistically significant differences in the levels of life satisfaction and psychological flourishing between believers in God and self-identified atheists. For this purpose, a sample of 821 participants (415 believers and 406 atheists) ranging from the ages of 19 to 85 years was selected. The results show that there is a slight average difference regarding life satisfaction and psychological flourishing between these groups; however, the difference is not substantial enough to ensure that believers in God or atheists have a better quality of life. Both believers and atheists exhibit high levels of life satisfaction and psychological flourishing. This study provides empirical evidence to demystify certain traditional assumptions about the supremacy of religious beliefs over secular convictions or vice versa. We hope that these findings create social awareness and could be used as a basis for future research concerning the population of non-believers.

KEY WORDS

Atheism; religiosity; well-being; psychological well-being; subjective well-being.RESUMEN

Existe poca literatura en Puerto Rico y América Latina que trate empíricamente asuntos relacionados al bienestar psicológico de la comunidad ateísta. El presente estudio tuvo como propósito analizar si existen diferencias estadísticamente significativas en los niveles de satisfacción con la vida y florecimiento psicológico entre creyentes en Dios y ateos identificados. Con este fin, se reclutó una muestra de 821 participantes (415 creyentes y 406 ateos) entre las edades de 19 y 85 años. Los resultados evidenciaron una ligera diferencia significativa en las medias de satisfacción con la vida y florecimiento psicológico entre los grupos, pero no lo suficientemente distante como para afirmar categóricamente que los creyentes o los ateos tienen una mejor calidad. Tanto creyentes como ateos, presentaron niveles robustos de satisfacción con la vida y florecimiento psicológico. El estudio aporta evidencia empírica a la desmitificación de ciertos postulados tradicionales sobre la supremacía de las creencias religiosas sobre las convicciones seculares o vice versa. Esperamos que estos hallazgos despierten la atención social y sirvan de base para futuras investigaciones con la población de no-creyentes.

PALABRAS CLAVE

Bienestar; bienestar psicológico; bienestar subjetivo; ateísmo; religiosidad.

Throughout history, the study of human well-being has been one of the most compelling and scrutinized subjects for a significant number of philosophers, theologians, and intellects. Nevertheless, it was not until four decades ago that this subject reached the thresholds of behavioral sciences and became an empirical and academic research topic in positive psychology (González-Rivera, Quintero, Veray-Alicea, & Rosario-Rodríguez, 2016). The main intent of this trend was to understand the factors and psychological processes that underlie the search for happiness and the development of a better quality of life. Wide empirical evidence consistently indicates that people, communities, and even countries with subjective well-being and happiness usually feel more satisfied with their lives, tend to live longer, and have a robust quality of life (Martínez-Taboas & Orellana, 2017).

The association of religiosity and spirituality with subjective and psychological well-being has been an emerging subject matter. There has been a continuous debate over whether religiosity has a direct effect on the well-being of individuals. The investigations available on this subject matter are characterized by a certain degree of discordance and empirical inconsistency. On one hand, there is scientific literature which substantiates that religious people are often more pleased with life than non-believers (Park & Slattery, 2013; Rule, 2006) or that there is a positive correlation between religiosity, life satisfaction, and well-being (Achour, Grine, Nor, & Yusoff, 2014; Harari, Glenwick, & Cecero, 2014). On the other hand, there are other studies which suggest that this connection is confusing or non-existent (Eichhorn, 2011; González-Rivera, Veray-Alicea, & Rosario-Rodríguez, 2017; Leondari & Gialamas, 2009). For example, even though Leondari and Gialamas (2009) indicate that religious beliefs and attending church could be associated to life satisfaction, they found that a belief in God is not related to any psychological well-being measure used in this study.

Within this context, in-depth, serious academic research should be conducted to determine how atheists describe their well-being and life satisfaction compared to the level of well-being of believers. This type of research would be helpful in clarifying certain assumptions, as of yet lacking empirical evidence, about the supremacy of religious beliefs, which permeates in common thinking as well as in behavioral disciplines. In fact, Martínez-Taboas, Varas-Díaz, López-Garay and Hernández-Pereira (2011) conducted a review of the literature in which they demonstrated that many behavioral professionals have historically characterized atheists as empty, lacking purpose in their lives, and being neurotic, antisocial, egotistical, and immoral. There is also a widespread belief at the grass-root level that atheists are insensible, satanic, cynical, and lustful people (González-Rivera, Pabellón-Lebrón, & Rosario-Rodríguez, 2017). Unfortunately, these types of stereotyped stances are simple personal opinions, are common in theistic societies and are lacking scientific validity. For that matter, Martínez-Taboas and Orellana (2017) explain that, prior to the year 2010, there was no empirical literature concerning the well-being of atheists.

Secular stigma and atheist identification

The lack of scientific literature in relation to the atheist community demonstrates the absence of interest that has prevailed throughout decades in the field of psychology. It is important to establish that an atheist does not adhere to the core principles of theism and does not believe in God or gods (Cliteur, 2009). In fact, as explained by Martínez-Taboas et al. (2011), not only do atheists not believe in God, they also assess God’s inexistence with absolute certainty. Furthermore, atheists have been classified into two categories by the scientific literature: (a) theological atheists: referring to people whom do not believe in God or gods; and (b) self-identified atheists: people whom identify themselves as atheists compared to other non-religious categories such as agnostics (Doane & Elliott, 2015).

Numerous national surveys suggest that approximately 5% of the American population does not believe in God or gods (Zuckerman, 2009). Providing that these countries are mainly Christian, there is plenty of literature available which identifies atheists as one of the most marginalized groups in the United States (Cragun, Kosmin, Keysar, Hammer, & Nielsen, 2012; Gervais & Norenzayan, 2013; Doane & Elliott, 2015). Also, it has been shown that there are approximately 32 countries in which the rights of those who openly identify themselves as atheists have been seriously violated (Sánchez, 2015). A study carried out in Puerto Rico with a sample of 348 atheists reported that 82% of the participants have perceived significant levels of discrimination (González-Rivera et al., 2017a). These results are not surprising, providing that distrust towards atheists is directly linked and significantly correlated with the belief in God (Gervais, 2008).

Religion, atheism and well-being

It is important to highlight the most outstanding results found in the limited research sources available dealing with the well-being and life satisfaction of both atheists and believers. Several research studies associate religiosity and spirituality with an increase in psychological well-being (Dierendonck, 2005; González-Rivera, Quintero, Veray-Alicea, & Rosario-Rodríguez, 2017; Piedmont & Friedman, 2012). The results may vary when the elements of well-being are limited to institutionalized religion and exclude spiritual aspects or the search for the sacred or transcendental. Similarly, there has been a well-established reassertion in research that religious people report a higher level of well-being and life satisfaction (Abdel-Khalek, 2011; 2013). The question that arises is whether those high scores are statistically distant from the ones obtained from atheists and non-religious people. In this regard, Rule (2006) found that people with a favorable attitude towards religion show a remarkably higher level of satisfaction towards life than non-practitioners. Furthermore, a study carried out in India found that religiosity is positively associated with happiness, life satisfaction, self-esteem, and optimism (Abdel-Khalek & Singh, 2014).

Similarly, Edling, Rydgren and Bohman (2014) performed a study in Sweden to examine the relationship between religion and happiness in a sample of 2,942 youngsters. The results of the investigation indicated that having religious beliefs did not have a significant impact on happiness. In fact, the effect on happiness was due to variables related to the sense of belonging to a group or organization, regardless of religious affiliations. Moreover, Lim and Putnam (2010) suggest that the connection between religion and life satisfaction could be a result of the social support networks that emerge within church groups. The authors’ argument is that support networks based on religious faith are often more important in life satisfaction than other social links. The reason for this could be that people tend to find more meaning in things when the social exchange comes from someone with whom they share overall basic values and beliefs.

It has also been proven that culture and society have a powerful influence on the level of religiosity, spirituality, and subjective well-being (Diener, Tay, & Myers, 2011; Eichhorn, 2011). Since many individuals live in highly religious localities, they would like to obtain a certain degree of acceptance within their cultural framework, resulting in greater involvement in this type of activity. This association will, therefore, positively influence the level of subjective well-being (Eichhorn, 2011). On the other hand, in a study in Puerto Rico, Martínez-Taboas and Orellana (2017) performed a preliminary study with the participation of 190 individuals (55 = non-believers; 135 = believers) with the purpose of assessing the psychological well-being, life satisfaction, and psychological flourishing of religious believers and non-believers. The results indicated that the average differences reported in the three scales, between both groups, were not statistically significant.

There are very few investigations that elucidate topics on the well-being and quality of life of the atheist community; nevertheless, there are some studies worth highlighting and reviewing. For example, Moore and Leach (2016) administered various well-being and mental health measures to a substantial sample of subjects (n = 4,667) from diverse religious beliefs. They found that there are no significant differences between atheists and believers in these variables. The authors, therefore, concluded that their results do not empirically affirm the existence of mental health disparities between religious and secular individuals. Likewise, another study with a sample composed of atheists, Christians, and Buddhists by Caldwell-Harris, Wilson, LoTempio and Beit-Hallahmi (2011) did not find any significant difference among these groups in terms of psychological well-being measures and empathy. On the other side, in a study conducted by Baker, Stroope and Walker (2018), atheists demonstrated a better physical health and fewer psychiatric symptoms (e.g., anxiety, paranoia, obsession, and compulsion) compared to other secular people and believers in God.

Given the inconsistency of the comparative measures between atheists and believers in terms of their well-being and life satisfaction, Zuckerman, Galen and Pasquale (2016) decided to revise, analyze, and challenge these findings. The authors found that in prominently secular countries, atheists usually report strong levels of subjective well-being and life satisfaction, whereas in countries that are dominantly theists or Christians, believers usually attain slightly higher scores than those of atheists in life satisfaction and well-being measures. This outcome is not surprising given that, in strongly religious cultures, theist faith could lead to discrimination, hostility, intolerance, and violence towards atheists (Silberman, 2005), resulting in a disruption in the development of a good quality of life.

Research Justification and Purpose of the Study

Historically, Christianity has exercised a substantial influence on Puerto Rico. It has also been a significant cultural aspect in most Latin American countries. For the year 2010, 96.7% of the Puerto Rican population identified themselves as Christians (Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion & Public Life, 2012). Since colonial times, the Christian religion with most influence over Puerto Rican society has been Catholicism (69.7%), followed by Protestantism (25.1%). The rest of the Christian religions account for 1.9%, meaning the portion of Puerto Ricans who belong to either non-Christian or non-Protestants churches or sects. Given that Christians make up the majority groups in both Latin America and Puerto Rico, it can be said that they tend to feel more support among the population and that the focus has been towards them.

Thus, providing the scarcity of research in both Puerto Rico and Latin America concerning how the atheist community perceives their subjective and psychological well-being, the main objective of the present study is to analyze if there are any statistically significant differences in the level of life satisfaction (H1) and psychological flourishing (H2) between believers in God and self-identified atheists. This study aims to extend the scope of the preliminary findings reported by Martínez-Taboas and Orellana (2017) and to encourage the Latin American scientific community to explore these variables in future research using believer and non-believer samples.

METHODS

Participants

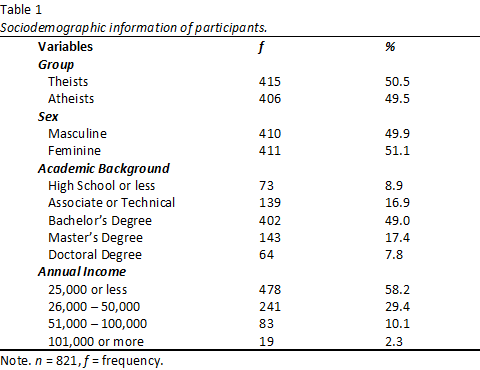

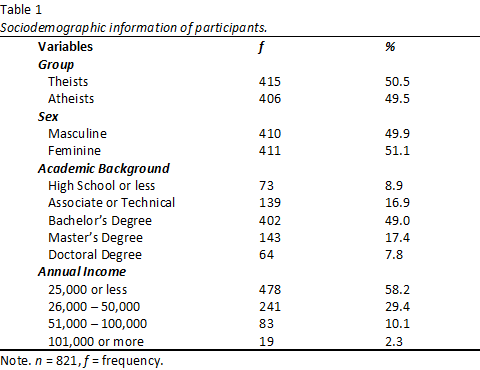

A non-probabilistic sample, consisting of 821 participants ranging from the ages of 19 to 85 years old, was selected by availability, of which 415 identified themselves as believers in God and 406 as atheists. Out of the 415 theist participants, only 215 attend church or regularly congregate with faith groups. The average age of the participants was 37.24 (DE = 13.30). The sociodemographic data of the sample is presented in Table 1. The following inclusive criteria was established for participation in the study: (1) being 21 years old or more, (2) being a Puerto Rican resident, and (3) being self-identified as a believer in a personal God (theist) or as an atheist (self-identified atheist). In this sample, agnostics, non-religious people, and deists (believers in one universal God who does not interact with humans) were excluded.

Measurement

Psychological Flourishing. We used the flourishing scale developed by Diener et al. (2010), which consists of eight items, to assess the psychological well-being from an eudaemonic perspective (e.g. I lead a purposeful and meaningful life; I am optimistic about my future). Each item has a scale of response of seven points which fluctuate from “fully disagree” to “fully agree”. The possible range is from 8 to 56 points. A high score characterizes a person with resilience and psychological resourcefulness. In the present study, the scale obtained an internal consistency index of .92 in Cronbach’s alpha.

Satisfaction with Life. The Spanish version of the satisfaction with life scale (SWLS) from Diener, Emmons, Larsen and Griffin (1985) was utilized. These authors believe that life satisfaction constitutes the cognitive component of subjective well-being. The instrument consists of five items in total (e.g., I am very satisfied with my life; In most ways my life is close to my ideal) with a response scale of seven points fluctuating from “totally disagree” to “totally agree”. The lowest score that can be obtained is 5 and the highest is 35. High scores suggest high life-satisfaction. In our study, the scale obtained an internal consistency index of .88 in Cronbach’s alpha.

General Data Questionnaire. To define the study sample, a sociodemographic questionnaire was elaborated to obtain age, sex, academic background, and annual income information, among other variables. It also contained dichotomous questions concerning the religious beliefs of the participants for theological identification: theist or atheist.

General Procedures

Once the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Carlos Albizu University (San Juan, Puerto Rico) approved the procedures for this study, the participant recruitment stage started. The data compilation was carried out through an online questionnaire using the PsychData platform for psychology research, which was active throughout the year 2017. During that period, a paid advertisement was circulated amongst popular social networks (such as Facebook, Twitter, Google+, WhatsApp, Instagram, among others) containing general information about the study and a link to access the online survey. Participants were authorized to share the advert, which resulted in a snowball effect throughout the social networks, speeding up the recruitment phase. Also, thanks to the collaboration of Atheists of Puerto Rico, an atheist activism organization who shared the advert in all their social networks, the participation of the non-believer community increased significantly.

Once the participants were able to access the online survey, they had to read the informed consent statement, which comprised the following clauses: (a) the purpose of the study, (b) the voluntary nature of the study, (c) possible risks and benefits, (d) the right to end the participation at any moment, (e) the name of the institution, and (f) the identification data and contact information of the researchers. It also indicated the participation duration time, as well as the right to obtain the results of the study once completed. To guarantee the privacy and confidentiality of the participants, the questionnaires were answered anonymously. Participants also had the choice to print the informed consent sheet.

Data Analysis

The current study is based on a descriptive non-experimental cross-sectional exploratory design. The computer software IBM SPSS Statistics (version 23) was used for the data analysis. Sample descriptive measures were obtained as part as the result analysis, the distribution of data normality and the reliability of the scales were analyzed, and group comparison and correlation analyses were carried out.

RESULTS

Before making the analysis to identify if there are significant differences in the levels of life satisfaction and flourishing between believers in God and atheists, an evaluation was performed regarding whether there was a normal data distribution of the variables mentioned. For this analysis, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov statistic with Lilliefors significance correction was used. The obtained results indicate that the data did not meet the normality distribution for life satisfaction between believers in God (KS(415) = .128, p < .001) and atheists (KS(406) = .143, p < .001), nor for flourishing in believers (KS(415) = .213, p < .001) and atheists (KS(406) = .201, p < .001). Since it did not meet the normality data distribution, a non-parametric analysis was used to test the hypothesis of this research.

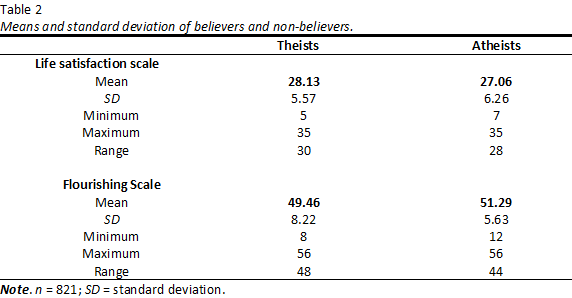

The Spearman correlation coefficient analysis was then performed for the life satisfaction and flourishing for the overall sample of the study. The results indicate that there is a moderate relation between life satisfaction and flourishing (rs = .63, p < .001). In addition, the descriptive data of both measures were calculated (see Table 2).

Life Satisfaction

The initial hypothesis sought to analyze if there are significant statistical differences between the level of life satisfaction between believers in God and atheists. For this, a group differences analysis using the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test was carried out. When analyzing if there are significant differences of life satisfaction between believers in God (Mrange= 429.87) and atheists (Mrange= 391.71), significant differences were observed, U = 76,412.50, Z = -2.311, p = .02, r = .08. These results imply that life satisfaction is higher among believers than in atheists, but this result has a small effect size. However, both groups are within the range of what is considered a high level of life satisfaction (Diener, 2006).

Having obtained the results and observing that both groups are within a high level of life satisfaction, an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was performed to determine if the results found in the Mann–Whitney U test were not biased by any other variable such as sex, age, income and academic background. Subsequently, a post hoc ANCOVA was conducted, introducing the participants' sex, age, income and academic background as covariants. In the Levene test, it was found that there is equality in the variance errors of the variables used (p > .05). The analysis showed that all covariates did not interfere in the statistically significant differences between believers in God and atheists. This confirms that there are statistically significant differences in the level of life satisfaction between believers in God and atheists [F (1, 815) = 8.27, p < .01, = .05]. Although the effect size for this analysis is small, and both groups are positioned at a high level of life satisfaction, statistically significant differences are evidenced in favor of believers in God, with slightly higher scores.

Psychological Flourishing

The second hypothesis sought to discover if there are statistically significant differences between the level of psychological flourishing between believers in God and atheists. Once more, the Mann–Whitney U test was used, given the lack of a normal data distribution for these variables. The results obtained indicate that there are statistically significant differences in the level of psychological flourishing between believers in God and atheists U = 97,776.00, Z = 4.017, p < .001, r = .14. Unlike the data obtained in the life satisfaction analysis, in this case, atheists (Mrange = 444.33) have a level of psychological flourishing which is statistically greater than that of believers in God (Mrange = 378.40). Nevertheless, the effect size is small and both groups are within a high level of psychological flourishing.

Since both groups have a high level of psychological flourishing, a post hoc ANCOVA was conducted, introducing the participants' sex, age, income and academic background as covariants. In the Levene test, it was found that there is equality in the variance erors of the variables used (p < .05). The results indicate that, by controlling the sex, age, income and academic background, there are statistically significant differences between the level of psychological flourishing between believers in God and atheists [F(1, 815) = 10.01, p < .01, = .04]. These results indicate that sex, age, income and academic background were variables that did not interfere in levels of psychological flourishing between believers in God and atheists. Although, the effect size is small and both groups are positioned at a high level of psychological flourishing, statistically significant differences are evidenced in favor of atheists, with slightly higher scores.

DISCUSSION

The objective of our research was to examine whether there are statistically significant differences in the levels of life satisfaction and psychological flourishing between believers in God and self-identified atheists. This is a particularly important issue due to the limited research within the Puerto Rican socio-cultural context on the subjective and psychological well-being of the country's atheist community. Studies such as this one serve to demystify the popular misperception regarding the emotional well-being of atheists, which has permeated in behavioral sciences, as well as academic settings. We emphasize that we do not intend to disparage the importance of faith in God nor understate the positive effects of religiosity that has been evidenced in many investigations. We rather intend to provide enlightenment on topics related to the well-being of atheists and believers and how they differ.

We have found statistically significant differences in the means of life satisfaction between atheists and believers, nevertheless, that differences has a small effect size. This result is in harmony with those reported by Park and Slattery (2013) and Rule (2006), who affirm that believers tend to be more satisfied with life than non-religious people. Nevertheless, this finding must be analyzed carefully so as not to reach previous conclusions. According to the categories developed by Diener (2006) for SWLS interpretation, scores between 25 and 29 reflect a high level of life satisfaction. According to these categories, in our study, the averages of atheists (M = 27.06) and believers (M = 28.13) yielded a high life satisfaction, since they only differ by one point. This means that the differences are statistically significant, yet not sufficiently pronounced as to categorically affirm that believers have a better quality and life satisfaction than atheists, that has confirmed by the small effect size. For Diener (2006), similar scores to the ones obtained in both of our groups (atheists and believers) represent a positive assessment of the main aspects of life: work, family, friends, leisure, and personal development. The author augments that people with this level of satisfaction can seek motivation and direction to address the areas of dissatisfaction in their life. Our study demonstrates that both groups possess this quality.

This leads us to question which common factors (if any) atheists and believers have that makes them feel satisfied with their lives. Authors such as Gallego, García and Pérez (2007) suggest that the freedom of people to be able to choose their beliefs, whether religious or non-religious, plays a transcendental role in their lives value and well-being. These authors found that the sense of freedom and meaning of life affirmed the religious self-definition of the participants as being either exceedingly firm believers or totally atheists. In this sense, the self-determination to be able to choose a religious or non-religious stance and the conviction in that belief makes people feel more secure, positive and satisfied with their life. In fact, there is evidence that conviction in religious or non-religious beliefs correlates with psychological health and with a positive worldview of life (Baker & Cruickshank, 2009; Wilkinson & Coleman, 2010). It has also been found that people who exhibit insecurity in their religious beliefs are those who report having a poorer quality of life (Brinkerhoff & Mackie, 1993). Since our study’s sample is composed of theists and self-identified atheists, this therefore strengthens and contributes evidence for those statements.

On the other hand, statistically significant mean differences were observed in psychological flourishing between atheists and believers with a small effect size. Our results are not aligned with the findings of Martínez-Taboas and Orellana (2017), Moore and Leach (2016), and Caldwell-Harris et al. (2011), who did not find differences in well-being and mental health measures between these groups either. We therefore infer that there must be other psychological variables that mediate the relationship of religious well-being and atheist well-being. Diener, Tay and Myers (2011) propose that having a defined purpose in life serves as a mediating factor between the variables of religiosity and happiness. Religious beliefs might satisfy the need for meaning and motivation of life; however, it should be stressed that they are one of the many optional paths to achieve a life with meaning. In this sense, atheists give meaning to their life by other means such as living in the present, sharing time with important people, loving their loved ones, or by directing their efforts towards a valuable goal without any divine or transcendental interventions.

Another aspect that must be taken into consideration is the sense of belonging and security that is obtained by sharing time with people who have similar beliefs. Various research has already proven that beyond religiosity itself—or the absence of it—there are variables linked to the sense of belonging to an organization or group, whether religious or not, which directly and positively impact the subjective assessment of happiness (Edling et al., 2014; Gervais, Shariff, & Norenzayan, 2011; Ten Kate, de Koster, & van der Waal, 2017). In other words, it is not the belief in God or atheism per se that makes people happy, but rather the social environment and sharing with people with the same convictions. Thus, it can be presumed that positive emotions, the increase of general well-being, and the feeling of belonging are attained through the social interaction among individuals of similar beliefs (Powell, Shahabi, & Thoresen, 2003). Even though atheists are one of the most marginalized groups in the world, they are emerging from anonymity and are unifying into groups and organizations to openly defend and share their beliefs. In fact, there has been a significant increase of secular, atheist, and politically active organizations, both locally and internationally, that identify themselves with the atheistic community (González-Rivera et al., 2017a).

At the theoretical level, our study makes a significant contribution to the insufficient literature available in Puerto Rico and Latin America on the subjective and psychological well-being of the atheistic community. Contrary to the dominant stereotypes in eminently Christian cultures, our results confirm that atheists exhibit robust levels of life satisfaction and psychological flourishing, therefore refuting popular beliefs of the apparent lack of meaning and purpose of atheists. Martínez-Taboas et al. (2011) reported that the international literature suggests that atheists tend to be inquisitive, liberal, undogmatic, non-authoritarian, and open to diversity. These attributes are important to qualify their lives as valuable, meaningful, and thriving at a psychological level. Our results demonstrate that, despite the constant marginalization atheists undergo in Puerto Rico (González-Rivera et al., 2017a), they have surprising psychological strength to face discrimination, while simultaneously maintaining high levels of well-being and happiness.

Regarding the practical implications, our study empirically strengthens certain postulates that are worth reviewing. First, it suggests that, in terms of psychological and subjective well-being, religiosity is useful, but it is not an essential factor in the pursuit of happiness. This outcome should promote respect and equanimity between people who profess different beliefs or seek different ways of attaining happiness. According to Zuckerman (2007), an atheist can make sense of life just by the pleasure of living it or because it is meaningful for his/her loved ones. In fact, he found that atheists find happiness and meaning in their lives through family relationships, in affinity with their community, highlighting unique and pleasurable moments of their lives, without waiting for any eschatological reward or eternal punishment after death. In this sense, our study provides empirical evidence against the preconceived biases that presume that atheists are miserable people, lacking meaning, and are devoid of hope and purpose. Such affirmations perpetuate discrimination against atheists and promote the supremacy of faith over non-traditional or non-religious beliefs.

Another important practical implication highlighted in our study is the need for behavioral professionals to include topics related to atheists, agnostics, non-believers, and secular life in their academic discussions. This step would contribute to the construction of a more multicultural and pluralistic society, where respect for diversity, different thinking, and non-traditional beliefs stands out. As Martínez-Taboas and Orellana (2017) explain, “social scientists must take the lead in this matter to break old schemes and replace them with credible and reliable information; moreover, we need theoretical models that fully explain the mind and lifestyles of non-believers” (p. 275).

Limitations and Recommendations

It is worth mentioning that the present study is the first in Latin America and the Caribbean that compares the levels of well-being of atheists and believers with such a strong sample size (n = 821). However, some limitations have been identified that readers and future researchers should take into consideration. First, the sample was collected by availability and not randomly. This type of sampling limits the generalization of the findings, which means that these results are only relevant to the participants in the study. Second, although it has been demonstrated that the collection of data over the internet is reliable, valid, reasonably representative, profitable, and efficient (Mayerson and Tryon 2003), this can affect the means of the study and increase the standard error. Lastly, since the study has a transversal design, readers should be careful with causal inferences, since it is unknown whether the results will be sustained over time.

Given the lack of research dealing with issues related to atheists and non-believers, we recommend further studies with this population from different perspectives and psychosocial approaches that may reveal a more complete profile of the atheist community. It is also necessary to carry out research and surveys and to collect statistical data that help us to establish a better profile and to learn the specific needs of the atheist community in Puerto Rico. A viable alternative is to encourage psychology graduate students to consider this topic for their dissertation work.

Conclusions

In summary, our results exposed that there are differences in the psychological and subjective well-being of the atheists and theists who were interviewed for the present study. The analysis revealed that believers show higher scores in life satisfaction, while atheists demonstrate higher scores in psychological flourishing. However, both believers and atheists presented robust levels of life satisfaction and psychological flourishing. This study breaks traditional assumptions, lacking empirical evidence, on the supremacy of religious beliefs that permeates within the popular imaginary and behavioral disciplines. We hope that these findings will awaken social attention and serve as a basis for future research with the non-believer population.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

FUNDING

The present study was self-financed.

REFERENCIAS

Abdel-Khalek, A. (2013). The relationships between subjective well-being, health, and religiosity among young adults from Qatar. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 16(3), 306-318. doi:10.1080/13674676.2012.660624

Abdel-Khalek, A.M., & Singh, A.P. (2014). Religiosity, subjective well-being and anxiety in Indian college students. The Arab Journal of Psychiatry, 25(1), 201-208. doi:10.12816/0006768

Achour, M., Grine, F., Nor, M. R. M., & Yusoff, M. Y. Z. (2014). Measuring religiosity and its effects on personal well-being: A case study of muslim female academicians in Malaysia. Journal of religion and health, 54(3), 984-997. doi:10.1007/s10943-014-9852-0

Baker, J. O., Stroope, S., & Walker, M. H. (2018). Secularity, religiosity, and health: Physical and mental health differences between atheists, agnostics, and nonaffiliated theists compared to religiously affiliated individuals. Social Science Research 75(1), 44-57. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2018.07.003

Baker, P. & Cruickshank, J. (2010). I am happy in my faith: The influence of religious affiliation, saliency, and practice on depressive symptoms and treatment preference. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 12(4), 339–357. doi:10.1080/13674670902725108

Brinkerhoff, M. B., & Mackie, M. M. (1993). Casting off the bonds of organized religion: A religious careers approach to the study of apostasy. Review of Religious Research, 34(3), 235–258. doi:10.2307/3700597

Caldwell-Harris, C.L., Wilson, A. L., LoTempio, E., & Beit-Hallahmi, B. (2010). Exploring the atheist personality: well-being, awe, and magical thinking in atheists, buddhists, and christians. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 14(7), 659-672. doi:10.1080/13674676.2010.509847

Cliteur, P. (2009). The definition of atheism. Journal of Religion and Society, 11(2), 1-23.

Cragun, R. T., Kosmin, B., Keysar, A., Hammer, J. H., & Nielsen, M. (2012). On the receiving end: Discrimination toward the non-religious. Journal of Contemporary Religion 27(1), 105-127. doi:10.1080/13537903.2012.642741

Diener, E. (2006). Understanding scores on the Satisfaction with Life Scale. Available in http://internal.psychology.illinois.edu/~ediener/Documents/Understanding%20SWLS%20Scores.pdf

Diener, E., Tay, L. & Myers, D. (2011). The religion paradox: If religion makes people happy, why are so many dropping out? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(6), 1278-1290. doi:10.1037/a0024402

Dierendonck, D. (2005). The construct validity of Ryff's Scales of psychological well-being and its extension with spiritual well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 36(1), 629-643. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00122-3

Doane, M. J., & Elliott, M. (2015). Perceptions of Discrimination Among Atheists: Consequences for Atheist Identification, Psychological and Physical Well-Being. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 7(2), 130-141. doi:10.1037/rel0000015

Edling, C. R., Rydgren, J., & Bohman, L. (2014). Faith or Social Foci? Happiness, Religion, and Social Networks in Sweden. European Sociological Review, 30(5), 615-626. doi:10.1093/esr/jcu062

Eichhorn, J. (2011). Happiness for believers? Contextualizing the effects of religiosity on life-satisfaction. European Sociological Review, 28(5), 583-593. doi:10.1093/esr/jcr027

Gallego, J. F., García, J. & Pérez, E. (2007). Factores del test purpose in life y religiosidad. Universitas Psychologica, 6(2), 213-229.

Gervais, W. M. (2008). Do you believe in atheists? Trust and anti-atheist prejudice (Disertación doctoral inédita). University of British Columbia,

Vancouver, Canadá. Available in https://open.library.ubc.ca/cIRcle/collections/ubctheses/24/items/1.0066560

Gervais, W. M., & Norenzayan, A. (2013). Religion and the origins of anti-atheist prejudice. In S. Clarke, R. Powell, & J. Savulescu (Eds.), Intolerance and conflict: A scientific and conceptual investigation (pp. 126–145). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof: oso/9780199640911.003.0007

Gervais, W. M., Shariff, A. & Norenzayan, A. (2011). Do you believe in atheists? Distrust is central to anti-atheist prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(6), 1189-1206. doi:10.1037/a0025882

González-Rivera, J. A., Pabellón-Lebrón, S., & Rosario-Rodríguez, A. (2017a). El rol mediador de la identificación ateísta en la relación entre discriminación y bienestar psicológico: Un estudio preliminar. Revista Puertorriqueña de Psicología, 28(2), 406-421.

González-Rivera, J. A., Quintero, N., Veray-Alicea, J., & Rosario-Rodríguez, A. (2016). Adaptación y Validación de la Escala de Bienestar Psicológico de Ryff en una Muestra de Adultos Puertorriqueños. Salud y Conducta Humana, 3(1), 1-14.

González-Rivera, J. A., Quintero, N., Veray-Alicea, J., & Rosario-Rodríguez, A. (2017). Relación entre Espiritualidad, Prácticas Religiosas y Bienestar Psicológico en una Muestra de Creyentes y No Creyentes. Revista Ciencias de la Conducta, 32(1), 25-56.

González-Rivera, J. A., Veray-Alicea, J., & Alicea, & Rosario-Rodríguez, A. (2017b). Relación entre la Religiosidad, el Bienestar Psicológico y la Satisfacción con la Vida en una Muestra de Adultos Puertorriqueños. Salud y Conducta Humana, 4(1), 1-12.

Harari, E., Glenwick, D. S., & Cecero, J. J. (2014). The relationship between religiosity/spirituality and well-being in gay and heterosexual Orthodox Jews. Mental Health, Religion and Culture, 17(9), 886-897. doi:10.1080/13674676.2014.942840

Leondari, A. & Gialamas, V. (2009). Religiosity and psychological well-being. International Journal of Psychology, 44(4), 241-248. doi:10.1080/00207590701700529

Lim, C., & Putnam, R. D. (2010). Religion, Social Networks, and Life Satisfaction. American Sociological Review, 75(6), 914-933. doi:10.1177/0003122410386686

Martínez-Taboas, A., & Orellana, E. (2017). Satisfacción con la vida, florecimiento y bienestar psicológico en personas ateas/agnósticas y personas teístas/deístas. In J. Rodríguez-Gómez (Ed.), La relevancia de las categorías de la espiritualidad y la religiosidad en la psicología contemporánea: Investigaciones puertorriqueñas (pp. 259-279). San Juan, PR: Publicaciones Gaviota.

Martínez-Taboas, A., Varas-Díaz, N., López-Garay, D., & Hernández-Pereira, L. (2011). Lo que todo estudiante de psicología debe saber sobre las personas ateas y el ateísmo. Revista Interamericana de Psicología, 45(2), 203-210.

Meyerson, P., & Tryon, W. W. (2003). Validating Internet research: A test of the psychometric equivalence of Internet and in-person samples. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 35(4), 614-620.

Park, C. L., & Slattery, J. M. (2013). Religion, spirituality, and mental health. In R. F. Paloutzian & C. L. Park (Eds.), Handbook of the psychology of religion and spirituality (pp. 540-559). New York, NY, US: Guilford Press.

Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion & Public Life. 2012. The global religious landscape: A report on the size and distribution of the world’s major religious groups as of 2010. Available in www.pewforum.org/files/2014/01/gl obal-religion-full.pdf

Piedmont, R. L. & Friedman, P. H. (2012). Spirituality, religiosity, and subjective quality of life. In K. C. Land, A. C. Michalos & M. J. Sirgy (Eds.), Handbook of Social Indicators and Quality of Life Research (pp. 313-329). EUA: Springer Netherlands. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-2421-1_14

Powell, L. H., Shahabi, L. & Thoresen, C. E. (2003). Religion and spirituality: Linkages to physical health. American Psychologist, 58(1), 36–52. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.58.1.36

Rule, S. (2006). Religiosity and Quality of life in South Africa. Social indicators Research, 81(2), 417-434. doi:10.1007/s11205-006-9005-2

Sánchez, A. (2015, 2 de abril). Ateos confesos: Entre la discriminación y la pena de muerte. InfoLibre. Buscado en http://www.infolibre.es

Ten Kate, J., de Koster, W., & van der Waal, J. (2017). The Effect of Religiosity on Life Satisfaction in a Secularized Context: Assessing the Relevance of Believing and Belonging. Review of Religious Research, 59(2), 135–155. doi:10.1007/s13644-016-0282-1

Wilkinson, P. J. & Coleman, P. G. (2010). Strong beliefs and coping in old age: A case-based comparison of atheism and religious faith. Ageing & Society, 30(2), 337-361. doi:10.1017/S0144686X09990353

Zuckerman, P. (2009). Atheism, secularity, and well-being: How the findings of social science counter negative stereotypes and assumptions. Sociology Compass, 3(6), 949-971. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9020.2009.00247.x

Zuckerman, P., Galen, L. W., & Pasquale, F. L. (2016). The Nonreligious: Understanding Secular People and Societies. New York: Oxford University Press.