http://dx.doi.org/10.24016/2018.v4n2.120

ORIGINAL PAPER

The decision of becoming a mother: Why some girls in foster group homes become adolescent mothers and others don’t?

La decisión de ser madre: ¿Por qué algunas jóvenes tuteladas se convierten en madres adolescentes y otras no?

Nair Elizabeth Zárate Alva 1 *, Josefina Sala-Roca 1 y Laura Arnau-Sabatés 1

1 Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, Spain.

* Correspondencia: nirzaranirzara@gmail.com

Recibido: 05 de marzo de 2018

Revisado: 22 de abril de 2018

Aceptado: 27 de abril de 2018

Publicado Online: 01 de mayo de 2018

CITARLO COMO:

Zárate-Alva, N., Sala-Roca, J., & Arnau-Sabatés, L. (2018). The decision of becoming a mother: Why some girls in foster group homes become adolescent mothers and others don’t?. Interacciones, 4(2), 71-79. http://dx.doi.org/10.24016/2018.v4n2.120

ABSTRACT

The aim of this research is to analyze which factors can explain why some girls in foster group homes become adolescent mothers and others do not, exploring the contraception use, life and motherhood expectations and their family models. The study also analyzes how teen mothers in foster group homes experience motherhood and analyze the experience of becoming mothers in their lives while in care. A total of 36 girls from foster group homes (18 mothers and 18 non-mother girls) were interviewed. The results show that the need to fill their emotional emptiness, their lack of professional life expectations, their unrealistic expectations about parenthood and the role of their partner, and the undervalue of the conditions necessary to raise their children are the main factors involved. Most of the girls in the mother group were teen mothers who were sent to foster homes because of their premature motherhood. This shows that the educative work done by caseworkers can help girls to be more conscious about getting the suitable conditions before becoming mothers. The role of foster parents, social educators, social workers and mentoring programs with the purpose to empower mothers to prevent children neglect is discussed.

KEY WORDS

Foster care, adolescent motherhood; contraceptives; life expectations; family relationships.

RESUMEN

El objetivo de esta investigación es analizar qué factores pueden explicar el por qué algunas jóvenes tuteladas se convierten en madres adolescentes y otras no. Explorando en ellas las temáticas relacionadas con el uso de anticonceptivos, sus expectativas de vida, la maternidad y sus modelos familiares. El estudio también analiza lo que implica una maternidad adolescente y estar tutelada. Se entrevistaron a 36 chicas tuteladas (18 eran madres y 18 no lo eran). Los resultados muestran que la maternidad adolescente a veces refleja la necesidad de llenar su vacío emocional, la falta de un proyecto de vida profesional, de expectativas poco realistas sobre la paternidad, el papel de su pareja, y la infravaloración de las condiciones necesarias para criar a sus hijos. La mayoría de madres adolescentes, fueron tuteladas a partir de su embarazo. Esto refleja que el trabajo educativo realizado por los educadores sociales, es de vital importancia para ayudar a las chicas a ser más conscientes sobre las condiciones adecuadas que se ha de tener antes de ser madre, y la necesidad de empoderarlas para prevenir posibles maltratos.

PALABRAS CLAVE

Jóvenes tuteladas; maternidad adolescente; anticonceptivos; expectativas de vida; relaciones familiares.

Teenage pregnancy continues to be a worldwide issue; where some adolescents become pregnant intentionally, while others don’t. Some international researches demonstrate that the poorer or less educated is the community, the higher is the chance for girls to become teenage mothers (Hobcraft & Kiernan, 2001; WHO, 2012). In Spain, adolescent pregnancies are 40% more likely to take place in those regions that are less developed (Delgado, 2011).

The rate of teenage pregnancy among girls in foster care is also often two to three times higher than the general adolescent population pregnancy rate (Mendes, 2009; Svoboda, Shaw, Barth, & Bright, 2012).

The teen pregnancy rate in the US for girls that are on foster care is twice higher than the US national teen pregnancy rate (Pecora et al., 2003). Courtney and coworkers (Courtney & Dworsky, 2005; Courtney et al., 2005), found in the Midwest Study that one third of the girls in foster care (33%) had been pregnant by the age of 17 and nearly half (48%) by the age of 19 and also were more than twice as likely to have one child by the age of 19 compared to their peers outside of the care system. Two years later, by the age of 21, two thirds (71%) of the females reported having been pregnant at least once and 62% had been pregnant more than once (Courtney, Dworsky & Pollack, 2007).

In Catalonia the rate of teenage motherhood in girls who are on foster care is higher than the teenage motherhood rate associated to their peers who are not in care. In a study done with a Catalan sample of young people in foster group homes, 30% of the teen girls in foster group homes became adolescent mothers (authors, 2009) whereas the motherhood rate among teens from the general population aged between 15 and 19 years was 8.1% in 2012 (INE, 2013).

Due to the high number of young women in foster care who got pregnant and the higher birth rates in girls that have been in care longer and have been sent to foster care (King, Putnam-Hornstein, Cederbaum, Needell, 2014), it seems important to consider what factors underlay these high rates of teenage motherhood. Different studies show that there are different factors that increase the risk of pregnancy, such as high sexual risk behaviors (Courtney, Dworsky, Lee, & Laap, 2010; James, Montgomery, Leslie, & Zhang, 2009) or being sexually active in an early age (Carpenter, Clyman, Davidson, & Steiner, 2001).

International studies also show evidences on different triggered factors underlying the teenage pregnancy and motherhood in girls in foster care, such as disrupted relationships with family and caregivers, poor educational access and attainment; and factors associated with abandonment and rejection in their relationships and the need “to be loved” (Chase, Maxwell, Knight & Aggleton, 2006).

The desire to have a family they did not have, to have a partner, to prove that they can be good parents who do not abandon their child and to raise a new adult identity by themselves are also factors that could have an influence on their decision to become mothers. Motherhood gives them a sense of stability, increased attachment and permanence (King, Putnam-Hornstein, Cederbaum, Needell, 2014; Love, McIntoch, Rosst, & Tertzakian, 2005; Pryce & Samuels, 2010).

Another factor could be associated with the lack of information and inconsistent education and sexual education (Boonstra, 2011). In the same vein, Connolly, Heifetz, & Bhor (2012), in their meta-synthesis reported that the lack of sexual education, the filling of wanting to do better, and the need of filling an emotional void through the child emerged as contributing factors to the teenage pregnancy and motherhood among girls in foster care. In a previous study, pointed out that the adolescent motherhood in girls in residential care seem to be more related to a lack of affective bonds than to difficulties accessing information and contraceptive methods. They highlighted other factors influencing motherhood including the favorable attitude of girls in care towards adolescent motherhood.

Nevertheless, a study carried out by Dworsky & Courtney (2010) shows that young people who remain in foster care beyond the age of 18 have a lower incidence of pregnancy than those who do not. Moreover, having the necessary supports contribute to positive motherhood experience (Connolly et al., 2012).

Despite all the factors mentioned above, it is important to note that for some of the girls in care, becoming mothers is a desire or a purpose in their life plans. In the Midwest study, 35% of girls who got pregnant between the age of 17 and 19 years old, wanted to get pregnant (Dworsky & Courtney, 2010). Similarly, in a subsample of girls in foster group homes in Catalonia, 28% of them reported that their main priority in their current life was to become a mother. In fact, motherhood and having a partner were the main priorities in their life even though they did not report any career expectations.

Teen motherhood seems to be associated with a number of negative consequences. Delgado (2011) highlighted the difficulties that Spanish teenagers experienced after becoming mothers in terms of low school performance and less job access and stability. These difficulties are higher for those young girls already belonging to a vulnerable group at high risk of social exclusion and marginalization such as young mothers who have grown up in foster care homes.

Some of the main adversities that teen mothers have to face with are related to the social isolation, the economic dependence, and the lack of emotional and practical support from their families and their partners, having in many cases problematic and sometimes violent relationships with them (Barn & Mantovani, 2007; Mendes, 2009). All these problems affect their life chances and possibilities of being economically independent and makes mothers in care and their children a highly vulnerable population. Several factors have been associated with infant neglect by young mothers (income, partner violence, smoking, mental health, etc) (Bartlett, Raskin, Kotake, Nearing & Easterbrooks, 2014). In fact, Peregrino (2014) found in Catalonia that the mothers of 11.8% of girls on foster care had also been on foster care.

Many studies also highlight the risk that young people on foster care have at establishing insecure affective bonds and attachment patterns (Cyr, Euser, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & van Ijzendoorn, 2010, Oriol, Sala-Roca & Filella, 2014) due to their previous story of trauma and maltreatment. The difficulties of building up secure attachment could be also a factor to explain the challenges in motherhood. On the other hand, most of the adolescent mothers in care have unrealistic child-raising expectations that are related to later parenting stress (Budd, Holdsworth & HoganBruen, 2006).

However, although they need to deal with many challenging situations during the motherhood, for many young mothers, motherhood has seen as a positive and stabilizing event in their lives (Connolly, et al., 2012). For many teen mothers, motherhood was seen as a “new beginning” that gave them a sense of purpose and belonging in their lives (Haight, Finet, Bamba, & Helton, 2009; Pryce & Samuels, 2010). For others, motherhood was also seen as a source of motivation in assuming a new role as mothers and a chance to give and receive love (Aparicio, Pecukonis, & O’Nale, 2015).

Some researchers have analyzed the high rates of adolescent motherhood comparing girls who are on foster care to girls who are not; nevertheless not all of the girls on foster care become adolescent mothers. Knowing what are the differences between girls on foster care who are mothers and those who are not could enrich our understanding of adolescent motherhood among this population. So, the aim of this research is to analyze which factors can explain why some girls in group homes become young mothers and why others don’t, exploring the contraceptive use, life and motherhood expectations and their family models references. Moreover, the study seeks to examine how teen mothers in foster group homes experience motherhood and analyze the experience of becoming mothers in their lives while in care.

METHODS

Participants

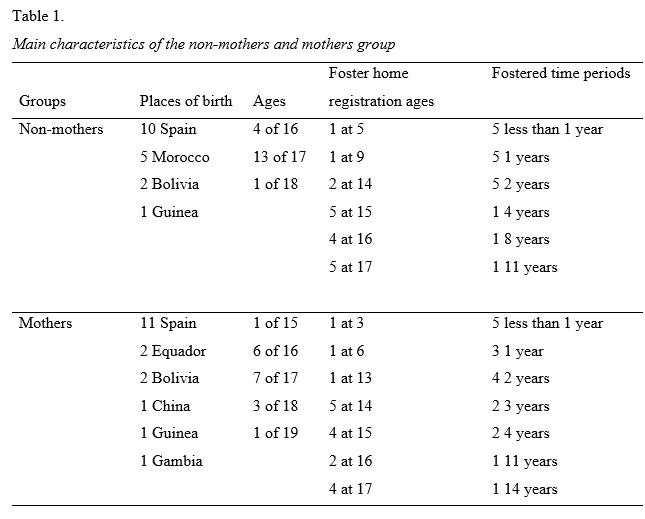

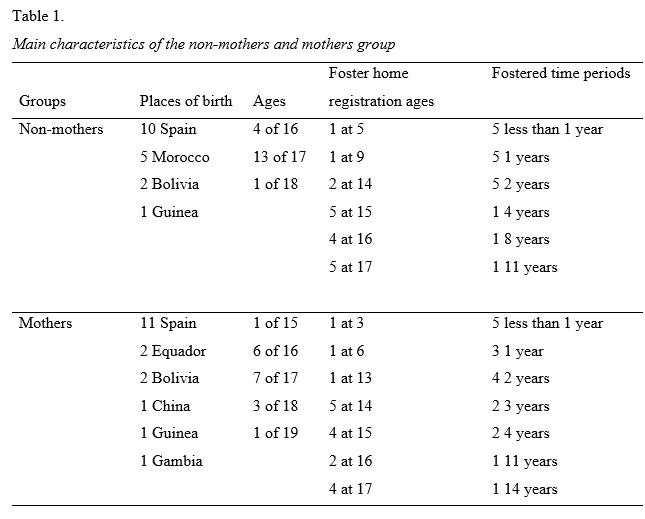

The sample consisted on 36 girls divided into two groups. The first group included 18 girls from two foster group homes (non-mother group), and the second group included 18 teen mothers from two foster group homes (mother group). The girls were between 15 and 19 years old. In the sample there were more Spaniard girls than foreigners. Most of the girls went to foster group homes after the age of 13. The main characteristics of the sample are summarized in table 1.

Instruments

The selected method to obtain information was the qualitative interview. This method was suitable for examining the adolescents’ beliefs, ideas and opinions. A semi-structured interview was designed. The topics of the qualitative interview were based on general data (age, nationality, etc.), information about beliefs, opinions, emotions, expectations and experiences about motherhood and family and about cultural models. This interview was validated by 16 experts.

Procedure

The girls were contacted through the group home managers. Their voluntary consent participation was requested, and they were informed that they could leave the interview at any time if they didn’t feel comfortable, they didn’t need to answer all the questions and the information they provided would be confidential. As they were minors, permission from their legal tutors was requested. The DGAIA (Direcció General d’Atenció a la Infància i Adolescència) gave permission to researchers to carry out the study. All the interviews were recorded so that they could be literally transcribed later. A content qualitative analysis was used by means of an inductive classification process using descriptive analysis scales.

RESULTS

Both groups have a mixture of Spaniard girls (10 non-mothers and 11 mothers) and immigrant girls (8 non-mothers and 7 mothers), with a range of ages between 15 and 19 years (average age 16.8 years old both groups) (table 1).

The average age at which the non-mother girls were sent to the foster care homes was 14.8 (SD 2.9). Similarly, the average age for their peers who were mothers was 14 (SD 3.6). But 14 of the mother girls were fostered because of the lack of support for their teen pregnancy.

Analyzing the ‘raw’ data collected from the interviews, four content dimensions emerged inductively: Family, lack of affection, cultural factors and family planning.

Family planning

Most of the non-mothers and teen mothers in foster care were familiar with condoms (14 and 16) and birth control pills (13 and 15) for contraception purposes. 11 non-mother girls used condoms and 8 of them used hormones. But fewer girls in the mother group used to use contraception methods before they got pregnant (7 out of 18 sexually active girls) than in the non-mother group (12 out of 15 sexually active girls).

When the girls who used to use contraception methods were enquired about the reasons to use them, most of them answered “to prevent pregnancy” (17 mothers and 10 non-mothers girls). Some non-mother girls also said “to prevent diseases” but none of the teen mothers did (7 vs 0, respectively). In fact 14 of the non-mothers in care used condoms and only 3 of the mothers did.

“The condom, because prevents pregnancy...” (Case 6-non-mother).

“The condom […] especially for not getting a sexual transmitted disease”. (Case 5-non-mother)

Eleven mothers said they didn’t used contraception methods before getting pregnant because they didn’t have enough information (4), they gave their partners the responsibility of using condoms and they didn’t use them (2), or they decided not to use them (2), or they didn’t have access to any contraception method (1), or they used the morning after pill (2). There were seven mothers who used contraception methods but two of them had their condom broken, and four of them stopped using the contraception methods (4). Four mothers reported that their decision for not using contraception methods was because they desired to get pregnant.

“No, because the first sexual relation I had was when I was 13 years old, and neither never got pregnant, nor I had the information”. (Case 11 – mother)

“I didn’t use nothing, but he used condoms sometimes”. (Case 16-mother)

When mothers were demanded to prioritize in their current life project motherhood, work, studies, partner, friends, leisure, 15 selected motherhood in the first place. The options selected in the first three positions were: motherhood (16), work (14), school (14), partner (8), friends (2) and leisure time (0). The non-mother girls selected in the first position; school (6). The options selected in the first three positions were: work (16), partner (13), school (12), motherhood (7), friends (6) and leisure time (0).

When mothers were enquired about how they see themselves in ten years, most of them pointed out that they would be with children (13) and partner (10). Some of them also mentioned work (12), having their own place (9), attending school (1) and making money (1). There were only three mothers that mentioned a professional project naming specific professionals areas where they would like to work or to study. The non-mother girls pointed out that they would be with partner (16) and children (15). Some of them also mentioned work (5), having their own place (6), and making money (2). None of them mentioned school and just one of them specified the kind of job she would like to perform.

“Well, be working and keep doing my best to raise my son”. (Case 11-mother).

“I would like to have 3 children […] I wouldn’t mind working, but I would prefer to do house work, raise my children and all that stuff”. (Case 4-non-mother).

When they were asked about what they would like to do when they become mothers, all the teen mothers said they would work and take care of their homes, but only 11 of the non-mother girls stated that. The other non-mother girls said that they will only work (4), or will only be housewife (3).

“I would work doing the house work and also work outside, trying to combine both. (Case 3-non-mother).

When they were enquired about the conditions necessary to have a baby, the teen mothers and non-mothers pointed out the need of having financial stability (17 and 18, respectively), partner support (7 and 8), responsibility (3 and 6) and have finished school (5 and 5) to become mothers. Mothers also pointed out their desired for not aborting the babies (7), the need of family support (5) and not feeling alone (2).

Family“Of course, I need to buy diapers, prepare the porridge, and that if I need to buy clothes, footwear, are all the things that the child needs, and without money, what can I do? The crib, the bathtub, his things. Without money you can’t have a child. It is an out of pocket cost…my God! (Case 2-non-mother).

Both groups have a traditional family concept. In fact teen mothers and non-mother girls have a negative attitude towards single-parent families (12 and 13, respectively).

“[Talking about the single-parent families] Terrible...Because I only had a mother and I feel bad for that...I would like to have my father at my side...my father and mom together...I think that is very important in a family relationship” (Case 1-non-mother)

Mothers and non-mother girls mentioned that the role of the fathers in a family is to be the financial provider (10 and 7, respectively), the main authority (3 and 7), care provider (7 and 6), educator (5 and 5) and affection provider (5 and 4). Both groups, mothers and non-mothers, believe that the mothers’ roles are: care provider (13 and 14), educator (8 and 6), affective provider (6 and 5) and financial provider (6 and 5).

“… [Talking about the father role] working and also being with the family, not everything is work ”. (Case 8- non-mother)

“[Talking about the mother role] being a housewife, both of them (mother and father) need to assume the responsibility in child education but this is frequently more suitable for the mother than the father. Mothers should take care of their child, watch them and be a housewife for both, the child and their husband. ” (Case 4-mother)

The family model experienced by mothers and non-mothers participants was a family where the mother had her first baby when she was young (20 and 18 years old, respectively). Most of them were abandoned by their husband (9 and 5) and some of them were also victim of domestic violence (2 and 6).

“I think my mother had her first baby at may age…I think she was 17 or 15 years old”. (Case 17-mother).

“… He came home drunk, argued with the child and did whatever he felt like…” (Case 31-non-mother).

Five of the non-mothers said they felt that they were prepared to become mothers; and 6 of the mothers felt that they were prepared before they became mothers.

“I was ready to have a child, because before being in foster care, I was baby-sitting my cousins and I already knew what that was”. (Case 17-mother)

When they were enquired about how they see their relationship with their children in the future, most of the mothers and non-mothers answer was “it would be good” (8 and 11), their relationship will be based on care (11 and 10), trust (9 and 6); and few of them described it as educative (3 and 4) or affective (4 and 4). Also some of the mothers said it was going to be stressful (4).

“…I think I will be a good mother because I will do everything in my power to have a good relationship with my son”. (Case 4-non-mother).

“I don’t think he will be attached to me but at least I would like him to trust me. I would let him know that I will always be there”. (Case 18-mother).

Lack of affection

Teen mothers stated that motherhood has helped them to feel better with themselves (15). Non-mothers also believe that (10).

“My life...I thought that I would be a looser as I had been lonely most of the time, but my son helped me to be more focused and also to be more mature... (Case 21-mother)

In fact most of non-mothers girls believe that they will succeed if they become adolescent mothers (10). The mother girls said that when they got pregnant they believed they would be able to take care of their child, and most of them reported that motherhood had bring them lots of positive emotions (13).

“Very happy... because having a child was what I wanted”. (Case 22-mother)

Twelve of the non-mothers girls have boyfriend. The nationalities of their boyfriends were: Spaniard (6), Latin-American (3), African (2) and French (1). All of the mothers have a boyfriend. Their nationalities were: Latin-American (10), Spaniard (5), African (2) and Chinese (1).

Cultural factors

The mothers said that in their culture the normal age to become a mother is 18 years old, and the non-mothers said 16.5. Most of them are in disagreement with that age (14 and 13).

“At 16, they are too Young, they are going too fast, they are not right, they have the excuse on the puberty age ...but you need to have a well-set head on your shoulders ”. (Case 3-non-mother)

Motherhood experience

Eleven mothers explained that they didn’t feel prepared to become mothers when they got pregnant, but 16 of them felt prepared when they were interviewed. Moreover, half of them experienced mainly negative emotions when they got pregnant such as being worried, overwhelmed, but after becoming mothers these emotions changed and turn into positive (13)

“I felt happy… it was what I wanted”. (Case 22-mother)

“My life… I thought that… as I have been lonely most of the time … that I would be a lost cause and my son made me settle down”. (Case 21-mother)

Most mothers explained that after getting birth their relationship with their partners got worse (13).

“Yes, always you have mistrust... thinking maybe he won’t love me...all his attention will be focused to the child... there were moments in which I felt very jealous... I can’t deny that...”. (Case 18-mother)

Some mothers explained that their expectations about partner relationship and family support after motherhood hadn’t been fulfilled. So 15 mothers believed that their partner would support them after motherhood, but only 8 received this support. Nevertheless three explained that the relationship with their partner became closer or that he had been more involved with their child. And all of the mothers believed that their families would support them, but only 11 received their support.

“Yes, at the beginning I had that support ... well… not really… to be honest I have never had his support… I would like that the father of my son helped me with the baby… because although a father is not as important as a mother like I said before, he could help… and all children love being with mom and daddy” (Case 21-mother).

DISCUSSION

Levels of teen pregnancy and adolescent motherhood in care are high in relation to the young people who are not in foster care (Courtney & Dworsky, 2005; Courtney, Dworsky & Pollack, 2007; Mendes, 2009; authors, 2009; Svoboda, Shaw, Barth, & Bright, 2012). Teen motherhood could be a difficult life event even when the person has support and favourable circumstances (Delgado, 2011), but it can be really challenging for young people in foster care due to their situation and the difficulties they need to face (housing, work, etc.) that increase their risk of being socially excluded.

Results of this research show that most of the mothers in foster group homes did not plan to get pregnant, even though some of them did express their desire to become a mother. Contrary to Bonostra (2011) and Connolly (2012) the lack of information was not one of the main factors for them for not using contraception methods. In the majority of the cases, the baseline seems to be related to the inconsistent and incorrect use of contraceptions, delegating in some cases the responsibility of that decision to their sexual partners. In the same vein, previous research showed that some young woman in foster care had a lack of self-confidence in communicating with their partners regarding safe sex (Chase, Maxwell, Knight, Aggleton, 2006).

It is worrying that most of the mothers and non-mother girls only reported using contraception methods for reducing pregnancy while just one third of the non-mother girls and none of the teen mothers said that they used contraception to prevent the risk of sexual transmitted disease. This fact could become problematic because girls in foster care and teen mothers in foster care chose a contraception method just to prevent pregnancy but not to protect themselves against sexually transmitted infections.

Regarding their current life priorities, mothers in care prioritized motherhood, work and school whereas girls in foster care prioritized work, having a partner and school and just a quarter of them prioritized motherhood. However, when they explained their future plans for the next 10 years, all of them (mothers and non-mothers) mentioned that motherhood and having a partner would be the main aim in their future life expectations to the detriment of their professional life. In fact, for the non-mother girls, work was just mentioned by 5 of them out of 18. They kept the desire to have the family they did not have with the traditional gender roles (Love, McIntoch, Rosst, & Tertzakian, 2005; Pryce & Samuels, 2010.

Authors found that girls in foster care don’t show any career project as their peers who are not in foster care. In our study only one non-mother teen gave some details about her profession project specifying the kind of work she wanted to have in the future. Our results show that many girls in foster care expect the male partner to assume the role to provide the financial support in the family even though many of them have seen their own mother was abandoned by their father. Actually, according to the literature, many girls when they became mothers, experience total financial dependency of their partners and families(Barn & Mantovani, 2007, Mendes 2009). It is also surprising that few mothers and non-mothers mention friends in their current life priorities if we consider that is one of the main adolescence sources of wellbeing (Navarro et al., 2015). In fact most of care leavers don’t have a peer social support network (Montserrat, Casas & Sisteró, 2016).

Nevertheless, two thirds of the teen mothers in foster care prioritized work as a way of sustaining themselves and their children; even though most of them stated that the role of the father is to provide financial resources. So, it seems that motherhood helped them adjust to their life/family expectations and made them more pragmatic and realistic. In fact less girls of the non-mother group pointed out that the father has the role of financial provider in a family. It’s possible that the more conscious the girls in foster care are about the need to have financial resources to become mothers, the stronger is the commitment with the use of contraception methods to prevent motherhood. In fact Author (2013) found that girls in foster care who used contraceptions express that their main objective to use them was to prevent pregnancy, even more than girls who are not in foster care.

Putnam-Hornstein & King (2014) found significant variations in the teen motherhood rate for girls in foster care depending on race/ethnicity. Mateos et al. (2014) also found that the sexual behaviors of girls at social risk are influenced by cultural factors and the family history. In this study most of the girls in foster care explained that in their culture, adolescent motherhood is quite usual. The age of reference is even lower for the girls in the non-mother group. In fact the age in which their mothers got birth for the first time was even lower for the girls in the non-mother group than the age of the girls in the mother group (18 vs 20). Nevertheless both groups stated that they don’t agree with that age. Actually, in both groups, mothers and non-mothers had similar proportion of girls from Spain and girls from other countries where adolescent motherhood is more usual. So even though the cultural factor can have some influence, it cannot explain by itself their decision to become mothers.

King, Putnam-Hornstein, Cederbaum, Needell (2014) also found higher birth rates in girls that have been in foster care longer and were fostered when they were adolescents. In the sample of our study this relationship has not been found; the ages in which they were sent to a foster care home and the time they had been in foster care were quite similar in both groups. Nevertheless, as these authors found, most of the girls in the mother group seem to have been sent to a foster care home because of the circumstances surrounding their teenage pregnancy. So it seems quite plausible to think that social educators in foster group homes try to make girls aware of the need to have financial stability to raise their children and provide girls with contraception methods. This is one of the variables that must be considered in future studies.

The mothers in foster care have a traditional idea of the family, they consider that the main father role is to provide financial resources, and the main mother role is to provide care and few of them pointed out to provide education or financial support. They wanted both parents at home, even though they didn’t have this experience and fewer than half pointed out the partner support as a condition to have their child, now that they have their baby. In fact most of the non-mother girls have boyfriends, when at their age most of the girls who are not in foster care don’t have any. As we have seen partners had an important place in their live project, but most of the mothers had experienced that their partners had not been involved in parenthood. In spite of the partners had abandoned them or their relationship had gotten worse, they said that motherhood made them feel better with themselves.

Another annoying question about their perception of the family role is that few of them pointed out the educative role. They see themselves as care providers, but do not seem to be conscious about the educative role of the parents. It seems that they don’t weight the responsibilities and real difficulties of parenthood. In fact most of the non-mother girls believe that they will succeed if they become adolescent mothers, however this doesn’t seem to be realistic as they don’t have family support, a job and a house to live.

The study provides evidences that motherhood is for girls who live in foster care, mothers and non-mothers, a way to feel better with themselves. The idea that motherhood helps to fulfill an emotional void has been also pointed out by other studies (Zárate, Arnau-Sabatés & Sala-Roca, 2017). .Pryce & Samuels (2010) pointed out also that motherhood can become a factor that can help girls to get over their trauma giving meaning to their life and a new identity because they realize that they can be good mothers and would not abandon their baby. It seems like the bonds that they created with their child could repair the insecure attachment style that they had with their own parents (Chase, Maxwell, Knight & Aggleton, 2006; Knight, Chase, & Aggleton, 2006).

Summarizing, for both groups of girls in care, mothers and non-mothers, motherhood would bring them some emotional wellbeing and don’t have other professional or vocational plans that widen their life expectations. Most of them have a traditional model of the family were the main role of father is to be the financial provider and the mother take care of the children. Most of them find teen motherhood something usual in their environment even though they don’t agree with that; and nearly all have enough information about contraceptive methods.

It seems that the main difference is that the non-mother group are more engaged with the correct use of contraceptive methods than the mothers. In the non-mother group there are also more girls who don’t expect a partner that become the financial provider and some of them don’t have a boyfriend. The non-mother girls have also a strong desire to become mothers, but it seems that motherhood is not the present priority in their lives.

So both groups of girls in care have common factors that could push them to an early motherhood, but the non-mother group seem to have to be more conscious about the motherhood responsibilities, and they seem to be less emotional dependent of their boyfriends. Most of the mothers group became pregnant when they were not in foster care. In fact, a few of the girls in the mother group come from foster group homes, so the social-educative intervention probably have an important role in reducing teen motherhood among girls in foster care.

Finally this study supports the need to introduce programs to help girls in foster care and in social risk to develop career projects that do not reduce their life projects only to motherhood and emotional partners; and to advocate for a responsible parenthood: making them awared about their responsibility as future mothers and to get an financial and suitable environment before becoming pregnant and having a baby. Most of the girls in foster care have parents that haven’t been able to provide them with education, financial and emotional stability. So they don’t have enough references to weight if they have reached the suitable conditions to grow up their children. Social educators, social workers and foster parents have an important role in this matter. Most of them are parents, and they can use their own experience to explain in the daily life what are their duties as parents, the importance of stability for the emotional and psychological development, etc. Foster parents and social educators must get conscious about their role to become key models for the future parenthood of the children in foster care whom they are responsible for. They cannot prevent the girls’ expectations and need to improve their emotional well being through building new attachment bonds with their own children, but they can show that to do it successfully they must get the necessary conditions before getting pregnant.

It seems that there is a consensus about the need to implement coordinated programs in multiple scenarios (educational, community and health) to prevent teen pregnancy (Molina et al., 2013). In the community approach one kind of promising program is motherhood mentoring since this kind of mentoring programs could increase not only the parenting knowledge, but also parenting skills, social support network, empower mothers and prevent parenting stress and neglect.

FUNDING

This study was financed by the Ministry of Education (EDU2010-16134). We want also to thank participant girls, their foster group homes and the Direcció General d’Atenció a la Infància I Adolescència (DGAIA).

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The author expresses that there are no conflicts of interest when drafting the manuscript.

REFERENCES

Aparicio, E., Pecukonis, E.V., & O’Nale, S. (2015). “The love that I was missing”: Exploring the lived experience of motherhood among teen mothers in foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 51, 44-54. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.02.002.

Barn, R., & Mantovani, N. (2007). Young mothers and the care system: Contextualizing risk and vulnerability. British Journal of Social Work, 37, 225-43. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bcl002.

Bartlett, J.D., Raskin, M., Kotake, C., Nearing, K.D. & Easterbrooks, M.A. (2014). An ecological analysis of infant neglect by adolescent mothers. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38, 723–734. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.11.011.

Boonstra, H. (2011). Teen Pregnancy Among Young Women In Foster Care: A Primer. Policy Review, 14(2), 8-19.

Budd, K.S., Holdsworth, M.J.A., & HoganBruen, K.D. (2006). Antecedents and concomitants of parenting stress in adolescent mothers in foster care. Child Abuse & Neglect, 30, 557–574. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.11.006.

Carpenter, S.C., Clyman, R.B., Davidson, A.J., & Steiner, J.F. (2001). The association of foster care or kinship care with adolescent sexual behavior and first pregnancy. Pediatrics, 108(3), e46. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.3.e46.

Chase, E., Maxwell, C., Knight, A. & Aggleton, P. (2006). Pregnancy and parenthood among young people in and leaving care: What are the influencing factors, and what makes a difference in providing support? Journal of Adolescence, 29(3), 437-451. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.01.003.

Connolly, J., Heifetz, M., & Bhor, Y. (2012). Pregnancy and Motherhood Among Adolescent Girls in Child Protective Services: A Meta-Synthesis of Qualitative Research. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 6(5), 614-635. doi: 10.1080/15548732.2012.72397.

Courtney, M., & Dworsky, A. (2005). Midwest evaluation of the adult functioning of former foster youth: Outcomes at age 19. Retrieved February 3, 2014 from Chapin Hall Center for Children at the University of Chicago web site: http://www.chapinhall.org/.

Courtney, M., Dworsky, A., & Pollack, H. (2007). When Should the State Cease Parenting? Evidence from the Midwest Study. Retrieved April 3, 2014 from Chapin Hall Center for Children at the University of Chicago web site: http://www.chapinhall.org/.

Courtney, M., Dworsky, A., Lee, J.S., & Raap, M. (2010) Midwest evaluation of the adult functioning of former foster youth: Outcomes at ages 23 and 24. Retrieved February 3, 2014 from Chapin Hall Center for Childrenat the University of Chicago web site: http://www.chapinhall.org/.

Courtney, M., Dworsky, A., Ruth, G., Keller, T., Havlicek, J., & Bost, N. (2005). Midwest evaluation of the adult functioning of former foster youth: Outcomes at age 19. Retrieved April 3, 2014 from Chapin Hall Center for Childrenat the University of Chicago web site: http://www.chapinhall.org/.

Cyr, C., Euser, E.M., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J., & van Ijzendoorn, M.H. (2010). Attach- ment security and disorganization in maltreating and high-risk families: A series of meta-analyses. Development and Psychopathology, 22, 87–108. doi: 10. 1017/S0954579409990289.

Delgado, M., Zamora F., Barrios Álvarez, L., & Cámara Izquierdo, N. (2011). Pautas anticonceptivas y maternidad adolescente en España. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas.

Dworsky, A., & Courtney, M. (2010). The risk of teenage pregnancy among tranistioning foster youth : Implications for extending state care beyond age 18. Children and Youth Services Review, 32(10), 1351-1356. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.06.002

Haight, W., Finet, D., Bamba, S., & Helton, J. (2009). The beliefs of resilient African- American adolescent mothers transitioning from foster care to independent living: A case-based analysis. Children and Youth Services Review, 31, 53–62. http://dx.doi. org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2008.05.009.

Hobcraft, J., & Kiernan, K. (2001). Childhood Poverty, Early Motherhood and Adult Social Exclusion. British Journal of Sociology, 52(3), 495–517. doi: 10.1080/00071310120071151.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística. (2013). Encuesta de fecundidad. Madrid: Instituto Nacional de Estadística.

James, S., Montgomery, S. B., Leslie, L. K., & Zhang, J. (2009). Sexual risk behaviors among youth in the child welfare system. Children and Youth Services Review, 31, 990–1000. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.04.014.

King, B., Putnam-Hornstein, E., Cederbaum, J.A., Needell, B. (2014). A cross-sectional examination of birth rates among adolescent girls in foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 36, 179–186. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.11.007.

Knight, A., Chase, E., & Aggleton, P. (2006). Teenage pregnancy among young people in and leaving care: Messages and implications for foster care. Adoption & Fostering, 30(1), 58–69. doi: 10.1177/030857590603000108.

Love, L., McIntosh, J.,Rosst, M., & Tertzakian, K. (2005). Fostering hope: Preventing teen pregnancy among youth in foster care. Washington: National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy.

Mateos, A., Balsells, A., Molina, M.A., Fuentes-Peláez, N., Pastor, C. & Amorós, P. (2014). Necesidades educativas para promover la salud afectiva y sexual en jóvenes en riesgo social. Reire 7(2), 14-27.

Mendes, P. (2009). Improving outcomes for teenage pregnancy and early parenthood for young people in out-of-home care: A review of the literature. Youth Studies Australia, 28(4), 11-18.

Molina, M.A., Amorós, P., Balsells, M.A., Jané, M., Vidal, M.J. & Díez, E. (2013). Sexual health promotion in high social risk adolescents: The view of ‘professionals’. Revista de cercetare, 41, 144-162.

Montserrat, C.; Casas, F. & Sisteró, C. (2016). Estudi sobre l’atenció als joves extutelats: 21 Evolució, valoració i reptes de futur. Barcelona: Departament de Benestar i Familia.

Navarro, D., Montserrat, C., Malo, S., González, M., Casas, F. & Crous, G. (2015). Subjective well-being, what do adolescents say? Child & Family Social Work. doi: 10.1111/cfs.12215

Oriol, X., Sala-Roca, J., & Filella, G. (2014). Emotional competences of adolescents in residential care: Analysis of emotional difficulties for intervention. Children and Youth Services Review, 44, 334-340. doi: 10.1080/13691457.2014.892475.

Pecora, P., Williams, J., Kessler, R., Downs, A., O’Brien, K.,Hiripi, E., & Morello, S. (2003). Assessing the effects of foster care: Early results from the Casey National Alumni Study. Seattle: Casey Family Programs.

Peregrino, A. (2014). Anàlisi del sistema de protecció dels infants i adolescents a la província de Lleida entre els anys 1990 i 2000. Tesi Doctoral. Barcelona: Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

Pryce, J., & Samuels, G. (2010). Renewal and risk: The dual experience of motherhood and aging out of the child welfare system. Journal of Adolescent Research, 25(2), 205–230. doi: 10.1177/0743558409350500.

Putnam-Hornstein, E. & King, B. (2014). Cumulative teen birth rates among girls in foster care at age 17: An analysis of linked birth and child protection records from California. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38, 698–705. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.10.021.

Svoboda, D., Shaw, T., Barth, R., & Bright, C. (2012). Pregnancy and parenting among youth in foster care: A review. Children and Youth Services Review, 34, 867–875. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.01.023.

WHO (2012). Adolescent pregnancy. Geneva: WHO.

Zárate, N.; Arnau-Sabatés, L. & Sala-Roca, J. (2017). Factors influencing perceptions of teenage motherhood among girls in residential care. European Journal of Social Work. doi: 10.1080/13691457.2017.1292397