https://dx.doi.org/10.24016/2026.v12.493

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Preliminary Psychometric

Properties of the Gratitude Questionnaire in Peruvian College Students: A

Comparison of the GQ-6 and GQ-5

Andrei Franco-Jimenez 1*

1 Universidad Nacional

San Luis Gonzaga, Ica, Peru.

*

Correspondence: andrei.franco@unica.edu.pe

Received: November 30, 2025 | Revised: January 22, 2026 | Accepted: February 11, 2026 | Published Online: February 14, 2026.

CITE IT AS:

Franco-Jimenez, A. (2026). Preliminary Psychometric

Properties of the Gratitude Questionnaire in Peruvian College Students: A

Comparison of the GQ-6 and GQ-5. Interacciones,

12, e493. https://doi.org/10.24016/2026.v12.493

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Gratitude is associated with psychological well-being and reduced

psychopathology; however, the widely used Gratitude Questionnaire-6 (GQ-6) has

shown inconsistent psychometric performance across cultures, particularly due

to Item 6. In Latin America, evidence suggests that the abbreviated GQ-5

performs better, but no validation study has been conducted in the Peruvian

context.

Objective: This study examined the psychometric properties of the Gratitude

Questionnaire-6 (GQ-6) and its revised version, the Gratitude Questionnaire-5

(GQ-5), in a sample of 444 Peruvian college students.

Method: Participants completed the Spanish version of the Gratitude

Questionnaire adapted by Quezada Berumen et al. (2023), along with additional

measures to assess convergent validity. We conducted Exploratory Graph Analysis

(EGA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to evaluate the dimensional

structure and model fit. We also assessed measurement invariance by sex and

internal consistency.

Results: The GQ-6 demonstrated poor fit indices; therefore, we removed Item 6,

and the remaining items constituted the GQ-5. The initial GQ-5 model still

required modifications; correlating the error terms between Items 4 and 5

yielded a good fit (χ²(4) = 8.762, CFI = 0.998, RMSEA = 0.052, TLI = 0.995,

SRMR = 0.018). The final GQ-5 model demonstrated acceptable internal

consistency (ω = 0.73) and measurement invariance across sex. It also showed

good convergent validity, correlating positively with self-efficacy (r = 0.31),

mindfulness (r = 0.34), and well-being (r = 0.20), and negatively with

depression (r = –0.26).

Conclusion: This adaptation underscores the importance of cultural adjustments and

supports the GQ-5 as a reliable tool for assessing gratitude among Peruvian

students in research and clinical contexts.

Keywords: gratitude, psychometrics,

students, factor analysis, surveys and questionnaires.

INTRODUCTION

Gratitude can be defined as the appreciation of what is valuable and

meaningful to oneself; it reflects a general state of thankfulness or

appreciation (Sansone & Sansone, 2010). Research has shown that gratitude

uniquely predicts psychological well-being beyond other personality traits, contributing

to dimensions such as environmental mastery, positive relationships, and

self-acceptance (Wood et al., 2009). Moreover, gratitude has been associated

with higher subjective well-being and reduced psychopathological symptoms

(Jans-Beken et al., 2018).

In recent decades, psychological research has increasingly focused on

gratitude in clinical contexts. The demonstrated effectiveness of gratitude

interventions in enhancing well-being (Kirca et al.,

2023), along with their accessibility and ease of implementation—ranging from

verbal or written expressions of gratitude to simple reflective practices—make

them valuable tools for promoting mental health (Diniz et al., 2023). Given

these implications, accurate measurement of gratitude is important for both

research and clinical practice, as it deepens our understanding of well-being

and informs targeted intervention strategies (Youssef-Morgan et al., 2022).

The Gratitude Questionnaire-6 (GQ-6), developed by McCullough et al.

(2002), is one of the most widely used instruments for measuring dispositional

gratitude, originally conceptualized as a unidimensional construct. It

comprises six items designed to capture the frequency and intensity of grateful

feelings. Subsequent research has evaluated the factorial structure of the GQ-6

using confirmatory factor analysis in diverse cultural contexts. While several

studies have replicated the proposed unidimensional structure, others have

reported poor global fit indices, thereby questioning the adequacy of the

original six-item model (Chen et al., 2009; Rey et al., 2018; Valdez et al.,

2017; Hudecek et al., 2020).

Consistent problems have been reported with Item 6, “Long amounts of

time can go by before I feel grateful to something or someone” (Hudecek et al.,

2020; Valdez et al., 2017; Rey et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2009). To address

these fit-related problems, researchers have removed this item, yielding a

modified version such as the GQ-5, which has shown improved psychometric

properties (Balgiu, 2020; Chen et al., 2009; Ling et

al., 2021).

The GQ-5 has demonstrated acceptable internal consistency across

different populations, with Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.70 to 0.80 (Balgiu, 2020; Chen et al., 2009; Ling et al., 2021). It has

also shown good convergent validity, correlating positively with life

satisfaction and positive affect, and negatively with depression (Balgiu, 2020; Hudecek et al., 2020; Langer et al., 2016).

These findings highlight the need to re-evaluate the factor structure of the

GQ-6 across different cultural settings and to consider adopting the GQ-5 when

appropriate.

Despite its extensive use, the GQ-5 and GQ-6 have not been

psychometrically evaluated in the Peruvian context. Given cultural variations

in the expression and experience of gratitude, validating these instruments in

Peruvian populations is important to ensure their appropriateness and accuracy.

Previous validations in Latin American countries, such as Chile (Langer et al.,

2016), Mexico (Quezada Berumen et al., 2023), and Ecuador (Lima-Castro et al.,

2019), provide a foundation but also highlight the need for country-specific

assessments due to cultural nuances.

Beyond cultural differences, it is also important to consider potential

gender variations in gratitude expression. Research indicates that women tend

to report higher levels of optimism and gratitude (Yue et al., 2017), whereas

men are less likely to experience and express gratitude (Kashdan et al., 2009).

Assessing measurement invariance across gender ensures that the instrument

provides valid and comparable results for both men and women, thereby

strengthening the robustness of the findings.

This study aims to evaluate the psychometric properties of the GQ-5 and

GQ-6 in a sample of Peruvian university students. Assessing these measures in

this context has important implications for both research and practice. A

reliable and valid gratitude scale enables researchers and practitioners to

develop targeted interventions to enhance well-being. Moreover, validating this

instrument facilitates cross-cultural comparisons and strengthens its

applicability across diverse populations. These adaptations highlight the need

to ensure that psychological assessments are culturally relevant to maintain

their accuracy and reliability (Chen et al., 2009; Hudecek et al., 2020; Ling

et al., 2021).

METHODS

Design

The study follows an instrumental design to analyze the psychometric

properties of a self-report instrument (Ato et al., 2013).

Participants

The sample consisted of 444 students from two private universities and

one public university in the city of Ica. The questionnaires were completed

virtually via Google Forms. The sample comprised 277 women (62.4%) and 167 men

(37.6%), with ages ranging from 18 to 48 years (M = 20.37; SD = 3.30).

Exclusion criteria included being at least 18 years old and completing all

requested data. A non-probabilistic convenience sampling method was used, as

individuals were selected based on the researcher's accessibility and study

requirements (Kerlinger & Lee, 2002), consistent with the study's

preliminary and exploratory nature.

Measures

Gratitude Questionnaire-6 (GQ-6): The GQ-6,

developed by McCullough et al. (2002), is a self-report six-item scale that

assesses individual differences in the tendency to experience gratitude in

daily life. In the present study, we used the Spanish version adapted by

Quezada Berumen et al. (2023). Responses range from 1 to 7 on a 7-point

Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree). Example items

include "I have so much in life to be thankful for" and "If I

had to list everything that I felt grateful for, it would be a very long

list." In Latin American contexts, internal consistency of the GQ-6, as

measured by Cronbach's alpha, has been reported as 0.75 in Chile (Langer et

al., 2016), 0.84 in Ecuador (Lima-Castro et al., 2019), and 0.79 in Mexico

(Quezada Berumen et al., 2023).

It is important to note that Item 6, "Long amounts of time can go

by before I feel grateful to something or someone," has been identified as

problematic in previous studies (Hudecek et al., 2020; Valdez et al., 2017; Rey

et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2009). Consequently, the GQ-5 is a modified version

of the GQ-6 that excludes this item. In Chile, this five-item version

demonstrated a Cronbach's alpha of 0.72, while in Ecuador it showed a

reliability coefficient of 0.93 among adolescents and adults.

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9): In this study,

we used the PHQ-9 as a self-administered scale to assess depressive symptoms.

The scale consists of nine items addressing depressive symptomatology

experienced during the two weeks prior to administration. Items are rated on a

Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). Example items

include "Little interest or pleasure in doing things" and

"Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless." The PHQ-9 has demonstrated

adequate reliability in Peruvian samples, with a reported Cronbach's alpha of

0.87 (Villarreal-Zegarra et al., 2019). In the current study, Cronbach's alpha

was 0.85.

General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSES): The GSES was

used to assess beliefs about personal competence in effectively responding to

various stressful situations (Baessler & Schwarzer, 1996). The GSES

consists of 10 items with a unidimensional structure and response options

ranging from 1 (incorrect) to 4 (exactly true). Example items include "I

can always manage to solve difficult problems if I try hard enough" and

"I am confident that I could deal efficiently with unexpected

events." The GSES has shown good internal consistency, with a Cronbach's

alpha of 0.81 in a Peruvian sample (Grimaldo et al., 2021). In the present

study, Cronbach's alpha was 0.91, indicating excellent reliability.

Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS-5): We used the

five-item brief version of the MAAS-5, as suggested in previous studies (Osman

et al., 2016; van Dam et al., 2010). The MAAS-5 assesses attention to

present-moment experiences through five items rated on a scale from 1 (almost

always) to 6 (almost never). Higher scores indicate greater mindfulness. We

used the Spanish translation by Caycho-Rodríguez et al. (2019a). The MAAS-5 is

suitable for assessing mindfulness in populations without prior meditation

experience. In a Peruvian college sample, the scale demonstrated good

reliability, with an omega coefficient of 0.83 (Caycho-Rodríguez et al.,

2019b). In the present study, Cronbach's alpha was 0.87, indicating strong

reliability.

World Health Organization-Five Well-Being Index (WHO-5 WBI): We used the

Spanish version of the WHO-5 WBI, developed by Simancas-Pallares et al. (2016),

as a brief screening measure of well-being. It consists of five items (e.g.,

"I have felt cheerful and in good spirits") with four Likert-type

response options (0 = never, 1 = sometimes, 2 = often, 3 = always). The total

score is obtained by summing item scores, with 0 indicating the absence of

well-being and 15 indicating high well-being. This scale has demonstrated

adequate psychometric properties in a Peruvian sample, with good internal

consistency (α = 0.85) (Caycho-Rodríguez et al., 2020). In the present study,

Cronbach's alpha was also 0.85.

Procedures

The instruments were administered virtually using Google Forms.

Participants were students from one public university and two private

universities in Ica, Peru, recruited through social media platforms. Informed

consent was obtained online, with participants informed that participation was

voluntary and anonymous. It was also specified that the data would be used

exclusively for academic purposes. Completion of the questionnaire required

approximately 10 to 15 minutes.

Data Analysis

The psychometric evaluation was conducted using R software version 4.1.2

(R Core Team, 2021) and the lavaan package (Rosseel

et al., 2012). Given the ordinal nature of the data, we used polychoric correlations to estimate relationships among

items, yielding more accurate factor loadings in factor analysis (Pendergast et

al., 2017).

We conducted confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to assess the fit of the

hypothesized factor structure using the weighted least squares mean and

variance adjusted (WLSMV) estimator. We evaluated model fit using RMSEA, SRMR,

CFI, and TLI. Acceptable fit was defined as RMSEA ≤ 0.07, CFI and TLI ≥ 0.95,

and SRMR ≤ 0.08 (Hair et al., 2010). We also reported the χ² statistic but did

not emphasize it due to its sensitivity to sample size.

In parallel, we implemented Exploratory Graph Analysis (EGA) using the EGAnet package (Golino & Christensen, 2021) to assess

dimensionality from a network psychometrics perspective. We estimated EGA using

the Gaussian Graphical LASSO (GLASSO) method with EBIC model selection (γ =

0.5) (Christensen & Golino, 2021) based on a polychoric

correlation matrix. The optimal penalty parameter (λ) was selected from a grid

of 100 values (ratio = 0.1). We conducted community detection using the Louvain

algorithm (Blondel et al., 2008) and assessed unidimensionality

by examining the number of detected communities. Additionally, we used the

Total Entropy Fit Index (TEFI) to evaluate global model fit.

We calculated reliability using the omega coefficient (McDonald, 1999)

as an alternative to Cronbach's alpha, addressing its limitations such as the

assumption of tau-equivalence (Cho, 2016; Sijtsma,

2009).

To examine measurement invariance, we followed the procedures

recommended by Wu and Estabrook (2016) and Svetina et al. (2020). We compared

configural invariance and threshold invariance across gender groups using the

WLSMV estimator. We evaluated invariance based on changes in CFI < 0.010 and

SRMR < 0.005 (Chen, 2007).

We examined convergent validity using Pearson correlations between the

GQ scores and the PHQ-9, GSES, MAAS-5, and WHO-5 WBI. Additionally, to assess

the relationship between the GQ-6 and its shortened version (GQ-5), we applied

a corrected Pearson correlation to account for spurious variance due to shared

items (Levy, 1967).

Ethical Aspects

This study adhered to the ethical principles outlined by the American

Psychological Association (2017). Before completing the survey, participants

received an informed consent form stating that participation was voluntary,

responses were anonymous, and data would be used exclusively for academic

purposes. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of

the Universidad Nacional San Luis Gonzaga (CEI-UNICA No017). All participants

were informed of the study and signed a consent form prior to participation.

RESULTS

We performed a polychoric correlation analysis

on the instrument's items, as presented in Table 1. The results indicate that

the correlations of Item 3, "When I look at the world, I do not see much

to be grateful for," and Item 6, "Long amounts of time can go by before

I feel grateful to something or someone," with the remaining items were

all below .40. This suggests weak correlations between these items and the rest

of the instrument.

Table 1. Descriptive

statistics of the GQ-6 items

|

Items |

Polychoric

correlations of the items |

M |

SD |

g1 |

g2 |

ri-t |

ω if item

deleted |

|||||

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

- |

5.61 |

1.63 |

-1.45 |

1.52 |

0.56 |

0.55 |

|||||

|

2 |

0.75 |

- |

5.28 |

1.52 |

-0.95 |

0.55 |

0.62 |

0.55 |

||||

|

3 |

0.16 |

0.16 |

- |

4.73 |

1.70 |

-0.45 |

-0.82 |

0.18 |

0.75 |

|||

|

4 |

0.56 |

0.58 |

0.08 |

- |

5.16 |

1.51 |

-0.91 |

0.49 |

0.49 |

0.61 |

||

|

5 |

0.61 |

0.56 |

0.17 |

0.61 |

- |

5.52 |

1.49 |

-1.24 |

1.23 |

0.52 |

0.61 |

|

|

6 |

-0.08 |

0.01 |

0.34 |

-0.07 |

-0.13 |

- |

3.90 |

1.59 |

0.13 |

-0.80 |

0.10 |

0.76 |

Note. M =

mean; SD = standard deviation; g1 = skewness; g2 = kurtosis; ri–t = corrected item–total correlation; ω = McDonald’s

omega.

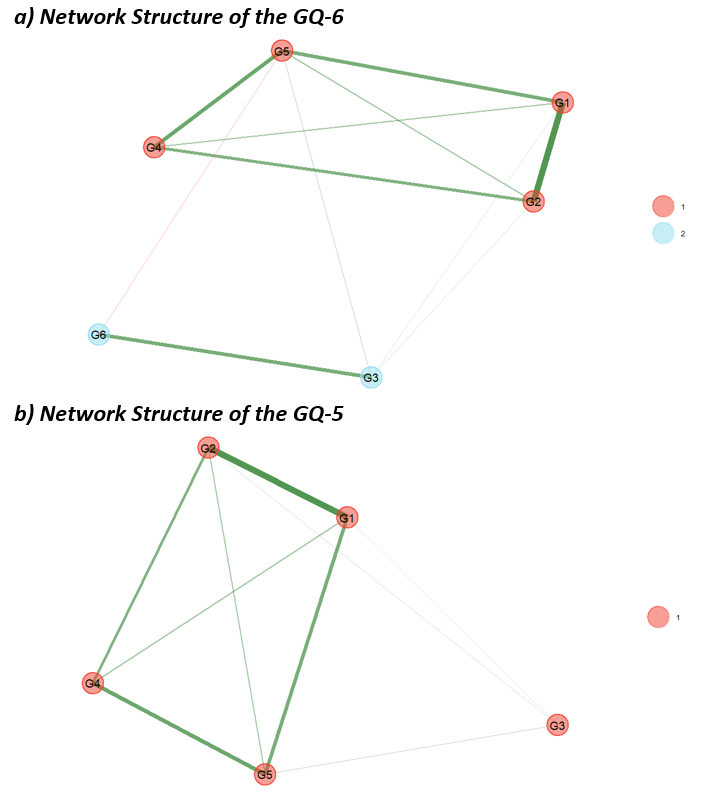

We conducted an Exploratory Graph Analysis (EGA) on both the six-item

(GQ-6) and five-item (GQ-5) versions. Figure 1a displays the network structure

of the GQ-6, whereas Figure 1b illustrates the GQ-5 version, which excludes

Item 6. The GQ-5 yielded a clear, unidimensional network: all five items formed

a single Louvain community, with a high edge density (0.900) and a TEFI of 0,

indicating no competing community solutions. In contrast, the GQ-6 produced a

two-community partition, a lower edge density (0.733), greater variability in

edge weights (Min = –0.062), and a negative TEFI (–3.102). These results

indicate reduced cohesion and suboptimal global fit. Together, these findings

suggest that Item 6 introduces noise or structural inconsistency, thereby challenging

the theoretical unidimensionality of the whole

questionnaire.

Figure

1. Exploratory Graph Analysis of the Gratitude

Questionnaire: Comparison between GQ-6 and GQ-5 Structures.

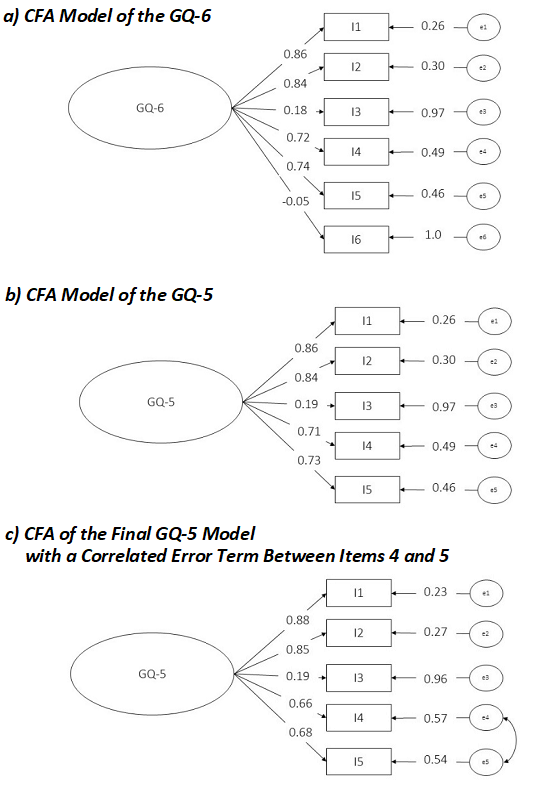

Table 2 presents the results of the CFA. The original unidimensional

GQ-6 model exhibited poor fit indices. These indices improved after removing

Item 6, as suggested in previous literature, resulting in the revised GQ-5

model. However, the RMSEA remained high. Therefore, we correlated the error

terms of Item 4, "I am grateful to a wide variety of people," and

Item 5, "As I get older, I find myself more able to appreciate the people,

events, and situations that have been part of my life history" (MI = 14.96).

We freely estimated this parameter in the final model.

Table 2. Fit Indices

of Three One-Factor Models for the GQ-5 and GQ-6

|

Models |

χ² |

df |

CFI |

TLI |

RMSEA |

SRMR |

|

GQ-6 |

196.11 |

9 |

0.918 |

0.864 |

0.217 |

0.086 |

|

GQ-5 |

39.84 |

5 |

0.984 |

0.969 |

0.125 |

0.035 |

|

GQ-5 model

with correlated errors terms between Items 4 and 5 |

8.76 |

4 |

0.998 |

0.995 |

0.052 |

0.018 |

Figures 2a–2c present the tested models. Figure 2a illustrates the

original GQ-6 model, Figure 2b depicts the GQ-5 model after removing Item 6,

and Figure 2c shows the final GQ-5 model, which includes correlated error terms

between Items 4 and 5. Across all models, Item 3 consistently exhibited low

factor loadings. Internal consistency analysis using the omega coefficient

indicated weak reliability for the GQ-6 (ω = .69), acceptable reliability for

the GQ-5 (ω = .76), and slightly lower reliability for the final model with

correlated error terms (ω = .73).

Figure

2. Comparison of Confirmatory Factor Analysis Models for

the Gratitude Questionnaire.

We conducted a measurement invariance analysis of the final GQ-5 model,

including correlated error terms, across two groups defined by sex, as

presented in Table 3. Configural invariance was supported based on the fit

indices. We then tested more restrictive levels of invariance, specifically

equal thresholds and equal loadings and thresholds across sex. These analyses

met the acceptable criteria for changes in CFI and SRMR (Chen, 2007).

Table 3. Measurement

Invariance of the Final GQ-5 Model Across Sex.

|

Model invariance |

χ2(df) |

CFI |

TLI |

SRMR |

ΔCFI |

ΔSRMR |

|

Configural |

26.254(8) |

0.992 |

0.981 |

0.030 |

- |

- |

|

Equal

thresholds |

45.205(28) |

0.993 |

0.995 |

0.030 |

0.001 |

0.000 |

|

Equal loadings

and thresholds |

38.745(32) |

0.997 |

0.998 |

0.030 |

0.004 |

0.000 |

Finally, we assessed convergent validity by examining the correlations

of the GQ-5 and GQ-6 with other psychological measures, as presented in Table

4. These measures included the PHQ-9 for depression, the GSES for

self-efficacy, the MAAS-5 for mindfulness, and the WHO-5 WBI for subjective

well-being. The GQ-5 showed significant correlations with these measures,

closely aligning with those of the GQ-6. A corrected Pearson correlation (Levy,

1967) indicated a strong association (r = .70) between the GQ-5 and GQ-6. Despite

the GQ-6's previously poor fit indices, we included it in this analysis for

comparison purposes.

Table 4. Correlations

of the GQ-5 and GQ-6 with Other Psychological Measures

|

Scale |

GQ-5 |

GQ-6 |

|

PHQ-9 |

-0.26 |

-0.27 |

|

GSES |

0.31 |

0.30 |

|

MAAS-5 |

0.34 |

0.35 |

|

WHO-5 WBI |

0.20 |

0.21 |

DISCUSSION

The present study aimed to evaluate the psychometric properties of the

GQ-5 and GQ-6 in a Peruvian sample, thereby contributing to the cross-cultural

validation of this widely used instrument. The findings indicate that the GQ-5,

derived from the GQ-6 by removing Item 6, demonstrates satisfactory

psychometric properties. Furthermore, correlating the error terms between Items

4 and 5 improved the model fit, supporting the utility of the GQ-5 for

assessing gratitude in the Peruvian context.

Consistent with previous studies across different cultures, Item 6,

"Long amounts of time can go by before I feel grateful to something or

someone," showed very low correlations with the other items, negatively

affecting the overall model fit. Removing Item 6 significantly improved the fit

indices, as reported by Hudecek et al. (2020), Valdez et al. (2017), and Balgiu (2020). This finding suggests that Item 6 may not

adequately capture the gratitude construct across cultural contexts, possibly

due to cultural nuances, differences in interpretation, or its reverse-scored

format. In addition, Chen et al. (2009) proposed that undergraduate students'

limited life experience may contribute to poor performance on Item 6. In

contrast, Langer et al. (2016) found that the five-item version was more

appropriate for younger populations.

In the final GQ-5 model, we correlated the error terms of Items 4 and 5.

We made this decision because both items explicitly refer to appreciation of

other people and share overlapping content, whereas the remaining items refer

to gratitude in more general terms. Notably, Fung (2024) also correlated these

error terms in his GQ-5 study, resulting in improved fit indices. Allowing this

residual correlation does not alter the unidimensional structure of the GQ-5 or

compromise the scale's construct validity.

The network analysis provides additional evidence of the GQ-6's

structural limitations. The EGA revealed a two-community solution for the

six-item version, with Item 6 clustering separately alongside Item 3. This

result is consistent with the CFA findings, which showed that Item 6 had poor

fit and was a candidate for removal. Notably, Item 6 was nearly disconnected

from the core gratitude cluster, and its strong association with Item 3 may

explain the low factor loading and residual correlations observed for Item 3 in

the CFA. In contrast, the reduced GQ-5 yielded a clear unidimensional

structure, with all five items forming a single cohesive community and showing

optimal global fit indices. Together, these findings support the exclusion of

Item 6 and reinforce the structural integrity of the five-item model.

Item 3, "When I look at the world, I do not see much to be grateful

for," exhibited a notably low factor loading in both the GQ-5 and GQ-6,

likely due to its reverse-scored format. Reverse-worded items often introduce

methodological challenges, such as increased cognitive load, which can lead to

misunderstanding or acquiescence bias (Suárez-Alvarez et al., 2018). Similar

issues with Item 3 have been reported in studies conducted in Chile (Langer et

al., 2016), Mexico (Quezada Berumen, 2023), Romania (Balgiu,

2020), Taiwan (Chen et al., 2009), and among Chinese and American adolescents

(Ling et al., 2021), where Item 3 consistently showed low factor loadings. This

low loading indicates that Item 3 did not contribute substantially to the

underlying gratitude construct in these samples. The consistency of this

pattern across cultures highlights the potential limitations of reverse-scored

items in the GQ-6. Future revisions of the questionnaire could consider

rephrasing or removing reverse-scored items to improve clarity and factorial

validity.

The analyses indicate that the GQ-5 demonstrates measurement invariance

between male and female participants. This finding is consistent with Balgiu (2020) and Rey et al. (2018), who also reported

measurement invariance across sex. Establishing measurement invariance allows

meaningful comparisons of gratitude levels between sexes in the Peruvian

context. It supports the use of the GQ-5 in both male and female samples in

cross-cultural research.

The internal consistency of the GQ-5, as indicated by McDonald's omega,

was acceptable and higher than that of the GQ-6. This result aligns with

previous studies reporting strong internal consistency for the GQ-5 (Balgiu, 2020; Ling et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2009; Fung,

2024), further supporting its reliability in assessing gratitude. These

findings suggest that, despite its small number of items, the GQ-5 provides a

reliable measure of gratitude across diverse populations.

The GQ-5 also demonstrated good convergent validity, as indicated by a

correlation of .34 with mindfulness. This association is consistent with

previous findings (Azad Marzabadi, Mills, & Valikhani,

2021; Swickert et al., 2019) and supports the

established relationship between these constructs. Mindful individuals are

generally more aware of and engaged in their present experiences, which

facilitates the recognition and appreciation of positive aspects of life and,

in turn, promotes gratitude. Similarly, individuals with higher levels of

gratitude may experience lower stress and fewer negative emotions, thereby

fostering a more mindful perspective (Azad Marzabadi

et al., 2021). In addition, we found a correlation of .31 between gratitude and

self-efficacy, indicating a meaningful association between these constructs.

This result is consistent with theoretical expectations, as both constructs are

positively related to adaptive psychological functioning (Datu & Yuen,

2020; Cousin et al., 2020).

Furthermore, we observed a correlation of .20 between gratitude and

subjective well-being, consistent with that reported by Kong et al. (2021).

According to Alkozei et al. (2018), two mechanisms

may account for this association. First, the cognitive framework proposes that

gratitude enhances the positive interpretation and recall of experiences,

thereby reducing negative thought patterns and promoting a healthier cognitive

style. Second, the psychosocial framework suggests that gratitude strengthens

interpersonal relationships and social support, thereby enhancing emotional and

physical well-being.

Consistent with previous research, we found a negative correlation

between gratitude and depression, comparable to the results reported by Langer

et al. (2016) (r = –.35), Rey et al. (2018) (r = –.47), and Dixit and Sinha

(2021) (r = –.30). Gratitude may enable individuals to reinterpret negative

experiences more positively, thereby reducing depressive symptoms through

increased resilience and personal growth. Moreover, gratitude enhances positive

emotions such as joy and satisfaction, which may counteract the reduced

positive affect commonly observed in depression (Lambert et al., 2012).

The findings of this study indicate that the GQ-5 has strong

psychometric properties, supporting its use as a reliable measure of gratitude.

This result is particularly relevant given the growing body of research

demonstrating the effectiveness of gratitude interventions in improving

well-being and reducing symptoms of depression and anxiety (Diniz et al., 2023;

Kirca et al., 2023). A rigorously validated

instrument supports both clinical practice and research by enabling accurate

assessment of gratitude and its association with mental health outcomes.

Limitations

Despite its strengths, this study has several limitations. The sample

may not fully reflect the diversity of the Peruvian population, limiting the

generalizability of the findings. Future research should include larger, more

diverse samples and employ longitudinal designs to examine the stability of the

gratitude construct over time and across demographic groups.

Conclusion

Removing Item 6 from the GQ-6 improved the scale's factor structure and

reliability, yielding the GQ-5, a version supported by the literature and

demonstrating satisfactory psychometric properties in a Peruvian context. In

addition, establishing measurement invariance across sex enables meaningful

comparisons between male and female participants. The scale also shows

appropriate correlations with related psychological constructs, supporting its

use in research and clinical practice. Overall, the GQ-5 represents a reliable

instrument for assessing gratitude among Peruvian students in both research and

clinical settings.

ORCID

Andrei Franco-Jimenez: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8648-834X

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

Andrei Franco-Jimenez:

Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data Curation,

Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization.

FUNDING SOURCE

This study was self-funded

by the author. No external financial support or institutional funding was

received.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Not applicable.

REVIEW PROCESS

This study has been reviewed by two external reviewers in double-blind

mode. The editor in charge was David Villarreal-Zegarra. The review process is

included as supplementary material 1.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The author declares that the

data supporting this study are available from the author upon reasonable

request.

DECLARATION OF THE USE OF GENERATIVE ARTIFICIAL

INTELLIGENCE

ChatGPT was used exclusively for minor

language polishing and wording refinement.

The final version of the manuscript was entirely

reviewed and approved by the

author.

DISCLAIMER

The authors are responsible for all statements made in this article.

REFERENCES

Alkozei,

A., Smith, R., & Killgore, W. D. S. (2018). Gratitude and subjective

wellbeing: A proposal of two causal frameworks. Journal of Happiness

Studies, 19(5), 1519–1542. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-017-9870-1

American

Psychological Association. (2017). Ethical principles of psychologists and

code of conduct (2002, amended effective June 1, 2010, and January 1,

2017). https://www.apa.org/ethics/code/

Ato,

M., López-García, J. J., & Benavente, A. (2013). Un sistema de

clasificación de los diseños de investigación en psicología. Anales de

Psicología, 29(3), 1038–1059. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.29.3.178511

Azad

Marzabadi, E., Mills, P. J., & Valikhani, A.

(2021). Positive personality: Relationships

among mindful and grateful personality traits with quality of life and health

outcomes. Current Psychology, 40(3), 1448–1465. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-0080-8

Baessler,

J., & Schwarzer, R. (1996). Evaluación

de la autoeficacia: Adaptación española de la Escala de Autoeficacia General [Measuring generalized self-beliefs: Spanish adaptation of the General Self-Efficacy Scale]. Ansiedad

y Estrés, 2(1), 1–8.

Balgiu,

B. A. (2020). The reliability and the construct validity of the Gratitude

Questionnaire (GQ-6) in a sample of Romanian undergraduates. Journal of

Educational Sciences and Psychology, 10(1), 101–109.

Blondel,

V. D., Guillaume, J.-L., Lambiotte, R., & Lefebvre, E. (2008). Fast

unfolding of communities in large networks. Journal of Statistical

Mechanics: Theory and Experiment, 2008(10), P10008. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-5468/2008/10/P10008

Caycho-Rodríguez,

T., García Cadena, C. H., Reyes-Bossio, M., Cabrera-Orosco, I., Oblitas

Guadalupe, L. A., & Arias Gallego, W. L. (2019b). Evidencias

psicométricas de una versión breve de la Mindful Awareness Attention Scale en estudiantes universitarios [Psychometric evidence of a brief version of

the Mindful Awareness Attention Scale in college students]. Revista Argentina de Ciencias del Comportamiento, 11(3), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.32348/1852.4206.v11.n3.24870

Caycho-Rodríguez,

T., Ventura-León, J., Azabache-Alvarado, K., Reyes-Bossio, M., &

Cabrera-Orosco, I. (2020). Validez e invariancia factorial del Índice de

Bienestar General (WHO-5 WBI) en universitarios peruanos. Revista Ciencias

de la Salud, 18(3), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.12804/revistas.urosario.edu.co/revsalud/a.9797

Caycho-Rodríguez,

T., Ventura-León, J., Martínez-Munive, R., & Barboza-Palomino, M. (2019a).

Traducción y validez de contenido de una escala breve de mindfulness para

adolescentes peruanos. Enfermería Clínica, 29(5), 308–312.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enfcli.2018.10.002

Chen,

F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit

indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A

Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(3), 464–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701301834

Chen,

L. H., Chen, M.-Y., Kee, Y. H., & Tsai, Y.-M. (2009). Validation of the

Gratitude Questionnaire (GQ) in Taiwanese undergraduate students. Journal of

Happiness Studies, 10(6), 655–664. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-008-9112-7

Christensen,

A. P., & Golino, H. (2021). On the equivalency of factor and network

loadings. Behavior Research Methods, 53(4), 1563–1580. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-020-01500-6

Cho,

E. (2016). Making reliability reliable. Organizational Research Methods, 19(4),

651–682. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428116656239

Cousin,

L., Buck, H., Benitez, B., Mills, P., & Redwine, L. (2020). A structural

equation model of gratitude, self-efficacy, and medication adherence in

patients with stage B heart failure. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 35(6),

E18–E24. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCN.0000000000000721

Datu,

J., & Yuen, M. (2020). Students’ connectedness is linked to higher

gratitude and self-efficacy outcomes. Children and Youth Services Review,

116, 105210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105210

Diniz,

G., Korkes, L., Tristão, L. S., Pelegrini, R., Bellodi,

P. L., & Bernardo, W. M. (2023). The effects

of gratitude interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Einstein,

21, eRW0371. https://doi.org/10.31744/einstein_journal/2023RW0371

Dixit,

S. K., & Sinha, J. (2021). Adaptation and validation of the Gratitude

Questionnaire (GQ-6) for the Indian context. Current Psychology. Advance

online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02143-2

Fung,

S.-F. (2024). Evaluating the psychometric properties of the Gratitude

Questionnaire in a Chinese sample: Comparing the 6-item and 5-item versions. Mindfulness,

15(9), 2321–2329. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-024-02433-3

Golino,

H., & Christensen, A. P. (2021). EGAnet:

Exploratory Graph Analysis – A framework for estimating the number of

dimensions in multivariate data using network psychometrics (R package

version 1.2.4). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=EGAnet

Grimaldo,

M., Correa, J., & Calderón-De la Cruz, G. (2021). Evidencias psicométricas

de la Escala de Autoeficacia General (EAG) en universitarios peruanos. Ansiedad

y Estrés, 27, 132–139. https://doi.org/10.5093/anyes2021a18

Hair,

J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate

data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson.

Hudecek,

M. F. C., Blabst, N., Morgan, B., & Lermer, E. (2020). Measuring gratitude in Germany:

Validation study of the German version of the Gratitude Questionnaire–Six Item

Form (GQ-6-G) and the Multi-Component Gratitude Measure (MCGM-G). Frontiers

in Psychology, 11, 590108. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.590108

Jans-Beken,

L., Lataster, J., Peels, D., Lechner, L., &

Jacobs, N. (2018). Gratitude, psychopathology and subjective well-being:

Results from a 7.5-month prospective general population study. Journal of

Happiness Studies, 19(6), 1673–1689. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-017-9893-7

Kashdan,

T. B., Mishra, A., Breen, W. E., & Froh, J. J. (2009). Gender differences

in gratitude: Examining appraisals, narratives, the willingness to express

emotions, and changes in psychological needs. Journal of Personality, 77(3),

691–730. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00562.x

Kerlinger,

F. N., & Lee, H. B. (2002). Investigación

del comportamiento: Métodos de investigación en ciencias sociales. McGraw-Hill Interamericana.

Kirca,

A., Malouff, J. M., & Meynadier, J. (2023). The effect of expressed

gratitude interventions on psychological well-being: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled studies. International Journal of

Applied Positive Psychology, 8, 63–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-023-00086-6

Kong,

F., Yang, K., Yan, W., & Li, X. (2021). How does

trait gratitude relate to subjective well-being in Chinese adolescents? The

mediating role of resilience and social support. Journal of Happiness

Studies, 22(4), 1611–1622. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-020-00286-w

Lambert,

N. M., Fincham, F. D., & Stillman, T. F. (2012). Gratitude and depressive

symptoms: The role of positive reframing and positive emotion. Cognition & Emotion, 26(4),

615–633. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2011.595393

Langer,

Á., Ulloa, V., Aguilar-Parra, J. M., Araya-Veliz, C., & Brito, G. (2016). Validation

of a Spanish translation of the Gratitude Questionnaire (GQ-6) with a Chilean

sample of adults and high schoolers. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 14,

1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-016-0450-6

Levy,

P. (1967). The correction for spurious correlation in the evaluation of

short-form tests. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 23(1), 84–86.

https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679(196701)23:1%3C84::AID-JCLP2270230123%3E3.0.CO;2-2

Lima-Castro,

S., Peña-Contreras, E., Aguilar-Sizer, M., Bueno-Pacheco, A., &

Arias-Medina, P. (2019). Adaptación y validación del Cuestionario de Gratitud

GQ-6 para el contexto ecuatoriano. Avaliação

Psicológica, 18(2), 129–137. https://doi.org/10.15689/ap.2019.1802.15689.03

Ling,

Y., Yang, Q., Zeng, Y., & Huebner, E. S. (2021). Assessing

the measurement invariance of the Gratitude Questionnaire–5 in Chinese and

American adolescents. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 24, Article

e17. https://doi.org/10.1017/SJP.2021.19

McCullough,

M. E., Emmons, R. A., & Tsang, J.-A. (2002). The grateful disposition: A

conceptual and empirical topography. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 82(1), 112–127. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.1.112

McDonald, R. P. (1999). Test theory: A unified treatment.

Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Osman,

A., Lamis, D. A., Bagge, C. L., Freedenthal, S.,

& Barnes, S. M. (2016). The mindful attention awareness scale: Further

examination of dimensionality, reliability, and concurrent validity estimates. Journal

of Personality Assessment, 98(2), 189–199.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2015.1095761

Pendergast,

L. L., von der Embse, N., Kilgus, S. P., &

Eklund, K. R. (2017). Measurement equivalence: A non-technical primer on

categorical multi-group confirmatory factor analysis in school psychology. Journal

of School Psychology, 60, 65–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2016.11.002

Quezada

Berumen, L. (2023). Estudio de validez y confiabilidad

del Cuestionario de Gratitud-6 (GQ-6) en México. Acta de Investigación

Psicológica, 13(1), 42–52. https://doi.org/10.22201/fpsi.20074719e.2023.1.476

R

Core Team. (2021). R: A language and

environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical

Computing. https://www.R-project.org/

Rey,

L., Sánchez-Álvarez, N., & Extremera, N. (2018). Spanish

Gratitude Questionnaire: Psychometric properties in adolescents and

relationships with negative and positive psychological outcomes. Personality

and Individual Differences, 135, 173–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.07.005

Rosseel,

Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural

equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48, 1–36. https://doi.org/10.18637/JSS.V048.I02

Sansone,

R. A., & Sansone, L. A. (2010). Gratitude and well being:

The benefits of appreciation. Psychiatry (Edgmont),

7(11), 18–22.

Sijtsma,

K. (2009). On the use, the misuse, and the very limited usefulness of

Cronbach’s alpha. Psychometrika, 74(1), 107–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11336-008-9101-0

Simancas-Pallares,

M., Díaz-Cárdenas, S., Barbosa-Gómez, P., Buendía-Vergara, M., &

Arévalo-Tovar, L. (2016). Propiedades psicométricas del Índice de Bienestar

General-5 de la Organización Mundial de la Salud en pacientes parcialmente

edéntulos. Revista de la Facultad de Medicina, 64(4), 701–705. https://doi.org/10.15446/revfacmed.v64n4.52235

Suárez-Álvarez,

J., Pedrosa, I., Lozano, L. M., García-Cueto, E., Cuesta, M., & Muñiz, J.

(2018). Using reversed items in Likert

scales: A questionable practice. Psicothema,

30(2), 149–158. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2018.33

Svetina, D., Rutkowski,

L., & Rutkowski, D. (2020). Multiple-group invariance with

categorical outcomes using updated guidelines: An illustration using Mplus and the lavaan/semTools packages. Structural Equation Modeling, 27(1),

111–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2019.1602776

Swickert,

R., Bailey, E., Hittner, J., Spector, A., & Brittaney, B. (2019). The

mediational roles of gratitude and perceived support in explaining the

relationship between mindfulness and mood. Journal of Happiness Studies, 20(3),

815–828. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-017-9952-0

Valdez,

J. P., Yang, W., & Datu, J. A. (2017). Validation of the Gratitude

Questionnaire in Filipino secondary school students. The Spanish Journal of

Psychology, 20, e45. https://doi.org/10.1017/sjp.2017.51

Van

Dam, N. T., Earleywine, M., & Borders, A. (2010). Measuring mindfulness? An

item response theory analysis of the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale. Personality

and Individual Differences, 49(7), 805–810.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.07.020

Villarreal-Zegarra,

D., Copez-Lonzoy, A., Bernabé-Ortiz, A.,

Melendez-Torres, G. J., & Bazo-Alvarez, J. C. (2019). Valid group

comparisons can be made with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9): A

measurement invariance study across groups by demographic characteristics. PLOS

ONE, 14(9), e0221717. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0221717

Wood,

A., Joseph, S., & Maltby, J. (2009). Gratitude predicts psychological

well-being above the Big Five facets. Personality and Individual

Differences, 46(4), 443–447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2008.11.012

Wu,

H., & Estabrook, R. (2016). Identification of confirmatory factor analysis

models of different levels of invariance for ordered categorical outcomes. Psychometrika,

81(4), 1014–1045. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11336-016-9506-0

Youssef-Morgan,

C. M., van Zyl, L. E., & Ahrens, B. L. (2022). The Work Gratitude Scale:

Development and evaluation of a multidimensional measure. Frontiers in

Psychology, 12, 795328. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.795328

Yue,

X. D., Hiranandani, N. A., Jiang, F., Hou, Z., & Chen, X. (2017). Unpacking

the gender differences on mental health: The effects of optimism and gratitude.

Psychological Reports, 120(4), 639–649. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294117701136