http://dx.doi.org/10.24016/2024.v10.439

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Psychometric properties of the sexual machismo scale (EMS-SEXISMO-12) in

adults

Propiedades psicométricas de la escala de machismo sexual

(EMS-SEXISMO-12) en adultos

Esther Gonzales Ortiz 1*

1 Universidad

César Vallejo, Lima, Peru

* Correspondence: egonzalesortiz96@gmail.com

Received: November 22, 2024 |

Revised: November 30, 2024 | Accepted: December 30,

2024 | Published Online: December 31, 2024

CITE IT AS:

Gonzales

Ortiz, E. (2024). Psychometric properties of the sexual machismo scale

(EMS-SEXISMO-12) in adults. Interacciones,

10, e439. http://dx.doi.org/10.24016/2024.v10.439

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Machismo is

explained as the system of beliefs, attitudes and behaviors based on the

polarization of the sexes and the superiority of the male gender. In the sexual

sphere, it is the control that is exercised over a woman in relation to the

expression of her sexuality under what is considered acceptable. Therefore, it

is considered convenient to have instruments to measure this variable. Objective:

The objective of this study was to determine the psychometric characteristics

of the sexual machismo scale (Ems-sexismo-12) in adults. Method: The

methodology used was of an applied nature, with a non-experimental approach and

instrumental design, applying the instrument to a sample made up of 530 adults

(M=308 and F=222) aged between 18 and 65 years, obtained through

non-probabilistic sampling by quotas of the districts of Piura. The content

validity, confirmatory factor analysis (WLSMV estimator), internal consistency

and reliability of the scale were evaluated. Results: The results showed

content validity in the items (Aiken's V > .70). For its part, after the confirmatory factor

analysis, a unidimensional structure was revealed with satisfactory

goodness-of-fit indices (CFI = .96; TLI = .95; RMSEA = .08; SRMR = .06). Likewise,

reliability is evidenced with acceptable values (ω = .83). Conclusion:

The EMS-12 scale proved to be a valid and reliable instrument for adults.

Keywords: Sexism, Adults,

psychometrics, validity, reliability.

RESUMEN

Introducción:

El machismo se explica como el sistema de creencias, actitudes y

comportamientos basados en la polarización de los sexos y la superioridad del

género masculino. En la esfera sexual, es el control que se ejerce sobre una

mujer en relación con la expresión de su sexualidad bajo lo que considera

aceptable. Por ello, se considera conveniente disponer de instrumentos para

medir esta variable. Objetivo: El objetivo de este estudio fue

determinar las características psicométricas de la escala de machismo sexual (Ems-sexismo-12)

en una muestra peruana. Método: La metodología utilizada fue de carácter

aplicado, con un enfoque no experimental y diseño instrumental, aplicando el

instrumento a una muestra conformada por 530 adultos (M=308 y V=222) con edades

entre 18 y 65 años, obtenida mediante muestreo no probabilístico por cuotas de

los distritos de Piura. Se evaluó la validez de contenido, análisis factorial

confirmatorio (estimador WLSMV), la consistencia interna y la confiabilidad de

la escala. Resultados: Los resultados mostraron validez de contenido en

los ítems (V de Aiken > .70). Por su

parte, tras el análisis factorial confirmatorio se reveló una estructura

unidimensional con índices de bondad de ajuste satisfactorios (CFI = .96; TLI =

.95; RMSEA = .08; SRMR = .06). Asimismo, la confiabilidad se evidenció con

valores aceptables (ω = .83). Conclusión: La escala EMS-12 demostró ser

un instrumento válido y confiable para adultos.

Palabras claves: Sexismo, Adultos, psicometría, validez, confiabilidad.

INTRODUCTION

Machismo is understood as the conviction, attitudes and behaviors that

are based on the polarization of the sexes or the radical distinction between

the feminine and the masculine and the conviction in the superiority of the

masculine in significant areas(Castañeda, 2019).

Sexual machismo is defined as the control of the man over a woman in

relation to the expression of her sexuality under what he considers acceptable;

It manifests itself through a lack of empathy, jealousy and even imposition

during the sexual relations (Silva and Zavala, 2020). Some authors consider

sexual machismo a manifestation of sexism that degrades women and is related to

several factors that negative affects the mental health (Mamani and Herrera,

2020).

Sexism can also be understood as a behavior that discriminates based on

the erroneous belief about the inferiority of women in general (Cameron in Moya

& Expósito, 2001). It occurs through jealous

behaviors, lack of empathy with the partner and sexual submission regardless of

the woman's desire (Silva and Zavala, 2020).

Glick and Fiske (1996) suggest that sexism is shown through two general

concepts represented by favorable and unfavorable attitudes towards women. In

this sense, unfavorable behaviors are considered hostile sexism, which

encompasses the classic and traditional form of sexism characterized by

antipathy and negative stereotypes towards women. Unlike benevolent sexism,

which despite being guided by positive feelings, are still sexist attitudes

that position women based on positive feelings such as protecting them and

providing them with the role of mother and wife. Likewise, benevolent sexism

could be used to cover up hostile sexism, however these may vary according to

the context in which the subjects relate. This theory considers a model that

constitutes hostile and benevolent sexism. These dimensions are classified into

paternalism, which refers to the distribution of power, also the gender

difference, and the last dimension that is related to sexuality when it focuses

on lack or dangerous sexuality, placing the man himself in a risk situation.

In our current reality, the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA, 2020)

in its report on the state of World Population announced that approximately 50%

of women in developing countries do not see their right to decide if they want

to maintain sexual relations with their partner, demonstrating how women lack

autonomy and freedom to choose the use of a contraceptive method or seek

medical attention.

On the other hand, the National Institute of Statistics (INEI, 2023)

indicates that 55.7% of women suffered some type of violence perpetrated by

their partner or romantic partner at some point in their lives. In Peru, sexist

positions are supported, as shown by the survey carried out by the Institute of

Peruvian Studies (IEP, 2023), which reflects that 37% of Peruvians consider it

appropriate for women to ask their partner's permission to go out, and a 14%

justify attacks by men.

The impact of machismo is not limited only to women since according to

the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO, 2019) the mortality rate in men is

related to masculinity behavior. dominant, which includes unprotected sexual

practices, violent relationships that can culminate in homicides, substance use

and other actions that put their health at risk. This is why the sexual

behaviors of a sexist man represent a risk factor for women, since it is

characterized by behaviors lacking responsibility, respect and consideration

(Díaz et al., 2010). Added to this, the culture associated with sexist gender

roles are factors associated with a greater risk of violence and HIV infection

for women (Cianelli et al., 2013).

Given this reality, the authors of the EMS-Sexism-12 scale considered it

pertinent to create a scale to evaluate beliefs and attitudes linked to

machismo to identify risk levels associated with the practice or tolerance of

it. This scale has research aimed at analysis and adaptation in international

contexts, such as Álvarez and Noreña (2023), who carried out an analysis of the

scale on machismo in a Colombian population; Camacho (2020) who conducted a

study on a sample of students from northern Mexico. On the other hand, in

Brazil López-Silva et al. (2020) conducted a study that sought to adapt a Scale

on Sexual Machism within the Brazilian population and

finally Herrera, et al. (2019) who analyzed psychometric properties of said

scale using a Chilean and Peruvian sample.

For its part, there are some contributions from national research such

as that of Huamani, et al (2023) who carried out a psychometric analysis in an

Arequipa population. Likewise, in the city of Lima, Sánchez (2022) investigated

the psychometric properties in the Lima population, as did Cajachagua

and Díaz (2022), who used a sample of young university students from the same

city. However, it is verified that despite the relevance of the topic, there

are few documents that have studied this variable within our context, which is

why the need arises to carry out an analysis on the validity of said instrument

on sexual machismo in a sample from Piura. Therefore, the following question

arises.

As described above, the present analysis mainly sought to determine

psychometric characteristics of the sexual machismo scale (Ems-sexismo-12) in

adults from the city of Piura, 2024. Likewise, specific purposes were sought

such as obtaining evidence based on the content of the EMS scale, also finding

evidence of the internal structure through confirmatory factor analysis of the

EMS and finally reviewing the reliability of the scale.

METHODS

Design

This study adopted a non-experimental design, which implies that no

stimulus or conditions other than their own are applied. Likewise, participants

are evaluated in their natural environment without modifying the situations or

the variable itself (Hernández-Sampieri & Mendoza, 2018). Likewise, this

study is considered instrumental or also known as psychometric, since within

this typology it is considered the study that examines psychological evaluation

instruments, whether they are new tests or to establish validation standards

(Ato, 2013).

Participants

The sample calculation was based on the general rule proposed by the APA

where it recommends working with samples of at least 300 participants as a

minimum sample (White, 2022). A non-probabilistic quota sampling was carried

out, including 530 adults, women (n= 308; 58.11%) and men (n= 222; 41.89%),

aged between 18 and 65 years, belonging to the 10 districts of the city of

Piura. Adults with cognitive or literacy difficulties and those who did not

consent to participation were excluded.

Instruments

The scale used was EMS-Sexism-12, developed by the authors Cecilia Díaz,

María Rosas and Mónica González in 2010 in Nuevo León-Mexico. The creation of

the scale was with the purpose of evaluating sexist behaviors, identifying

risks to sexual health and their levels of risk when tolerating sexism. This

scale demonstrated adequate levels of reliability through Cronbach's alpha

coefficient of 0.80. Furthermore, it showed adequate adjustment in CFI, GFI and

TLI validity indices, since they were greater than 0.9, an RMSEA value less

than .08 and a x2/df ratio = 0.3 (Díaz et al., 2010).

Procedure

Initially, a sample of 50 participants was taken for the purpose of a

pilot test and to verify the understanding of the items previously evaluated

through Aiken's V. Subsequently, we traveled to the city districts to access

the participants in person. Likewise, questionnaires were applied virtually

through Google forms, previously obtaining informed consent from each of the

participants.

Data analysis

A detailed examination was carried out, in which the relevant data were

analyzed and interpreted (Sánchez, et al., 2018). The present study was

subjected to the evaluation of seven judges specialized in the corresponding

area using Aiken's V coefficient, which allows verifying the relevance of the

items in relation to their content, based on the evaluations made by the

experts which, the closer Let the value be 1, it is understood as greater

content validity that will have greater content validity. (Ruiz and

Cornejo,2021)

The internal structure was evaluated through confirmatory factor

analysis (CFA), which allows identifying factors and analyzing their

relationship with each other (Segura, et al., 2014). In addition, indices that

indicated the level of fit to the model were

considered. Among them we find the square root of the mean of the squared

residuals (SRMR), for which a value of 0.08 is recommended for samples greater

than 100. Other relevant indices are the goodness of fit index (GFI), which

suggests a value greater than or equal to 0.93 (Cho et al, 2020), the RMSEA

index, whose value must be equal to or less than 0.05, the comparative fit

index (CFI), which must be greater than or equal to 0.95 (Lai, 2020), and the

Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), which is suggested to be greater than 0.90 (Xia &

Yang, 2019). Regarding incremental fit indices, such as the GFI, CFI and TLI,

it is established that a score equal to or greater than 0.90 is considered

adequate, while a score greater than or equal to 0.95 is considered optimal (Escobedo

Portillo et al., 2016). On the other

hand, there are authors who offer a more flexible perspective regarding the

main fit indices used in the analysis of models, Whittaker and Schumacker

(2022) argue that greater and equal scores consider scores greater than .90 for

CFI. and TLI as appropriate; On the other hand, RMSEA and SRMR indices less

than and equal to .80 are considered acceptable and those less than and equal

to .05 are considered optimal.

Ethical aspects

The research study presented is in accordance with the necessary

permissions to use the instrument from compliance with the ethical foundations

already established by the César Vallejo University (2022), which suggest

respecting and maintaining honesty throughout the research, as well as respect

for intellectual authorship and rights of researchers to avoid plagiarism. The

protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the César

Vallejo University. All participants were informed about the study and signed a

consent form before participating.

Likewise, the corresponding permissions will be requested from the

participants, respecting the guidelines recommended by the College of

Psychologists of Peru (2018), thus ensuring that the present study does not

entail unpleasant consequences or risks for the participants, and the

protection of their rights throughout the entire process. In addition, data

will be obtained through real processing respecting moral values and principles

during the study.

RESULTS

Table 1 presents the content validity of the

EMS-Sexism-12 in adults, assessed using Aiken's V coefficient. Seven judges

evaluated the items, determining all to be valid. The items demonstrated

adequate sufficiency, clarity, and relevance. Aiken's V is a measure used to

evaluate the relevance of items concerning their content based on the assessments

of multiple judges. The coefficient ranges from 0 to 1, with values closer to 1

indicating higher content validity. These results confirm the robust content

validity of the scale (Ruiz and Cornejo, 2021).

Table 1. Validity

indicators 95% CI for the scale items.

|

Items |

Sufficiency |

Clarity |

Coherence |

Relevance |

||||

|

IA |

p |

IA |

p |

IA |

p |

IA |

p |

|

|

1 |

1 |

0.008 |

1 |

0.008 |

1 |

0.008 |

1 |

0.008 |

|

2 |

1 |

0.008 |

1 |

0.008 |

1 |

0.008 |

1 |

0.008 |

|

3 |

1 |

0.008 |

1 |

0.008 |

1 |

0.008 |

1 |

0.008 |

|

4 |

1 |

0.008 |

1 |

0.008 |

1 |

0.008 |

1 |

0.008 |

|

5 |

1 |

0.008 |

1 |

0.008 |

1 |

0.008 |

1 |

0.008 |

|

6 |

1 |

0.008 |

1 |

0.008 |

1 |

0.008 |

1 |

0.008 |

|

7 |

1 |

0.008 |

1 |

0.008 |

1 |

0.008 |

1 |

0.008 |

|

8 |

1 |

0.008 |

1 |

0.008 |

1 |

0.008 |

1 |

0.008 |

|

9 |

1 |

0.008 |

1 |

0.008 |

1 |

0.008 |

1 |

0.008 |

|

10 |

1 |

0.008 |

1 |

0.008 |

1 |

0.008 |

1 |

0.008 |

|

11 |

1 |

0.008 |

1 |

0.008 |

1 |

0.008 |

1 |

0.008 |

|

12 |

1 |

0.008 |

0.86 |

0.008 |

1 |

0.008 |

1 |

0.008 |

Note. IA: Agreement Index

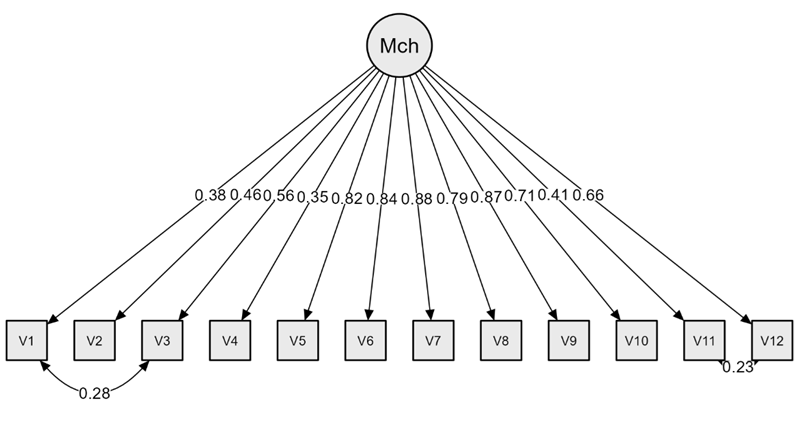

Figure 1 illustrates the confirmatory factor

analysis (CFA) of the EMS-Sexism-12. The evaluation followed the

goodness-of-fit criteria recommended by Whittaker and Schumacker (2022).

According to their guidelines, a Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis

Index (TLI) greater than 0.90 are considered acceptable for evaluating model

fit quality. Similarly, root mean square error of

approximation (RMSEA) and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) values

of ≤0.08 are deemed acceptable, with values ≤0.05 considered optimal.

Figure 1. Confirmatory

factor analysis with the DWLS method.

The original model yielded the following fit

indices: χ²/df = 6.5, p < .001; CFI = .94; TLI =

.92; RMSEA = .107; SRMR = .07. These results indicated that the unidimensional

model of the EMS did not fit the data adequately.

DISCUSSION

The present research had machismo as a study variable, which is defined

as the control exercised by a man over a woman in relation to the expression of

their sexuality (Silva and Zavala, 2020). These types of attitudes and

behaviors of superiority represent a latent risk due to their relationship with

violence (Huamani et al., 2019) and the increase in this in recent years (INEI,

2022; INEI 2023; MIMP, 2024). Likewise, it affects the right to sexual freedom,

decision-making and access to health, generating more inequality between

genders (UNFPA, 2020).

In our Peruvian context, it is important to validate a scale related to

machismo according to the indicators of violence and the machista

positions that justify it (IEP, 2023). That is why, under this premise, the

present study analyzed the psychometric properties of the EMS -12 by the

authors Díaz Rodríguez et al. (2010) in a Piura sample where both sexes were

considered, given that machismo is a problem that is not limited only to women

(PAHO, 2019).

To achieve the research objectives, the scale was subjected to

evaluation by a group of judges, the CFA and a reliability test. Based on the

results obtained, it was evident that the instrument is suitable for

application in Piura.

Likewise, it reflects a model that adjusts to the acceptable values of

the different analyses. Which agrees with the study by Huamani et al. (2019)

where the version of this unidimensional questionnaire is made up of 12 items

that represent the sexual machismo variable that obtained similar validity and

reliability values in a considerable sample of both sexes in the city of

Arequipa, a context belonging to the Peruvian reality and differs from the

study. In the same way, similar results were obtained to the study by Silva et

al., (2020) since the authors validated the unidimensional scale with

satisfactory adjustment indicators taking indicators such as CFI, RMSEA

obtaining a scale suitable for the Brazilian population. At a specific level,

we sought to obtain content validity of the EMS, through Aiken's V where the

elements of the scale were subjected to expert judgment, where values from 0.86

and 1.00 were found. This means that the items are valid as suggested by Ruiz

and Cornejo (2021), the values closest to 1 are understood as elements with

greater content validity, coinciding with the study carried out by Cajachagua and Díaz (2022) where the scale was subjected to

analysis by 7 expert judges who considered the reagents to be appropriate,

which implies adequate sufficiency, clarity, relevance and coherence for

application in the sample.

In the analysis of the validity of the internal structure through the

CFA with the unidimensional model, modifications of residual covariances were

made in items 1 “That only the man has sex before marriage” with Item 3 “That

only the man has sexual experience ” and Items 11 “The man must start his

sexual life in adolescence and 12” The man must make his son start his sexual

life” obtaining a respecified model. This residual covariance process coincides

with what was applied in the research of Herrera et al., (2020) where they

considered correlating items 1 and 3, managing to improve the model fit indices

in a Peruvian population, however, they were unable to confirm the model.

This final model achieved adequate fit indices, reporting indicators of

X2(df) = 219.02(52), p = .001; IFC = .96; TLI = .95;

RMSEA = .08; SRMR = .06. Taking as reference the goodness-of-fit measures

suggested by Whittaker and Schumacker (2022), who argue that scores greater

than 0.90 for CFI and TLI are considered adequate to evaluate the quality of

model fit. Likewise, the RMSEA index and SRMR that are less than or equal to

0.08 are considered acceptable. In turn, RMSEA and SRMR with values less than

or equal to 0.05 are classified as optimal.

The results of this finding differ from what was reported by Herrera

(2020) where, despite obtaining adequate validity indices, the original 12-item

model was not confirmed after eliminating one of them. However, it coincides

with the studies of Álvarez and Noreña (2023) in their research in the

Colombian Caribbean with satisfactory goodness-of-fit indices; GFI=.98;

CFI=.98; TLI=.97; RMSEA=0.08 and SRMR=.05. However, it differs from what was

obtained in the research study by Silva et al. (2020) in which the

goodness-of-fit indices are results.

Finally, the last objective was to establish the reliability of the

instrument applied to adults in the city of Piura, using the Omega coefficient,

obtaining from its only dimension a reliability score of .83 with a confidence

interval of 95%; being highly favorable for exceeding levels greater than 0.8,

this indicates that the scale is consistent over time and is within acceptable

reliability indices.

The result of the present study is supported by the various

investigations carried out previously that have shown that the EMS has

acceptable reliability values (Álvarez and Noreña, 2023; Herrera et al., 2020;

Huamani, et al., 2023). On the other hand, studies based on Cronbach's alpha

coefficient were observed that obtained adequate reliability values (Camacho,

2020; López-Silva et al., 2020). By observing these results, it can be

confirmed that this scale has stability in its results despite the time in which

it was created in the different populations in which it has been applied, both

young people and adults, as evidenced by studies carried out to date

demonstrating that it has a level of reliability that is applicable in various

Latin American populations.

Strengths and limitations of the study

Despite showing adequate validity and reliability of the scale, it is

necessary to consider some limitations, such as using non-probabilistic

sampling due to its accessibility to the sample; Considering probability

sampling could ensure a more representative sample, less risk of bias, and

better generalization of results. On the other hand, it is also considered

necessary to reduce the virtual application that may generate some biases in

the responses; however, a large part of the sample were in-person applications;

likewise, it would be ideal for these findings to complement each other. in our

context with invariance analysis and with other sources of validity, such as,

for example, evidence based on the relationship with other variables.

In clinical contexts, its application helps to identify problems related

to sexist attitudes or gender violence. The validation of the scale provides an

important basis that allows the design and implementation of prevention and

intervention programs in vulnerable populations, promoting relationships based

on mutual respect and reducing inequality gaps. Likewise, in social contexts,

it is useful to raise awareness among the population about gender equality,

prevent sexual violence and guide public policies.

Conclusion

Based on the previously established objectives, it is determined that

the psychometric properties of the sexual machismo scale have validity and

reliability indices, so it is concluded that the sexual machismo scale is a

valid and reliable instrument for its application in the Piura´s population.

ORCID

Esther Gonzales Ortiz https://orcid.org/0009-0008-8129-5213

AUTHORS’

CONTRIBUTION

Esther Gonzales Ortiz: Conception of the

manuscript, data collection, statistical analysis, interpretation of the data,

writing of the manuscript.

FUNDING

This research was self-funded.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author declare that he don’t have conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Not applicable.

REVIEW PROCESS

This study has been reviewed by external peers in double-blind mode.

The editor in charge was David

Villarreal-Zegarra. The review process is included as

supplementary material 1.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The authors attach the database as supplementary material 2.

DECLARATION OF THE USE OF GENERATIVE ARTIFICIAL

INTELLIGENCE

The author declares that he has not used tools generated by artificial

intelligence to create paper, nor technological assistants for writing. The

final version of the paper was reviewed and approved by the same author.

DISCLAIMER

The author is responsible for all statements made in this article.

REFERENCES

Álvarez, N., & Noreña ,

M. (2023). Psychometric Analysis of the Sexual Machism

Scale (EMS-12) in Colombian Caribbean university students. Avances en Psicología, 31(1), e2760. https://doi.org/10.33539/avpsicol.2023.v31n1.2760

Ato, M., López, J., & Benavente, A. (2013). A classification system for research designs in

psychology. Anales de Psicología / Annals of Psychology,

29(3), 1038–1059. http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.29.3.178511

Camacho, D. (2020). Propiedades psicométricas de la Escala de

Machismo Sexual (EMS-Sexismo-12) en una muestra del norte de México. Enseñanza

e Investigación en Psicología, 2(3), 424-429.

Castañeda, M. (2019). El machismo invisible. España: Editorial

Debolsillo.

Campo-Arias, A., & Oviedo, H. C. (2008). Psychometric properties of a scale: internal

consistency. Revista de salud pública, 10(5), 831-839.

Cho, G., Hwang, H., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, Ch. M.

(2020). Cutoff criteria for overall model fit indexes in generalizedstructured component analysis. Journal

of Marketing Analytics, 8, 189–202. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41270-020-00089-1

Colegio de Psicólogos del

Perú (2018). Código de ética profesional. Perú: Colegio de

Psicólogos del Perú.

Cianelli R, Villegas N, Lawson S, Ferrer L, Kaelber L,

Peragallo N, & Yaya A. (2013). Unique factors that place older Hispanic

women at risk for HIV: intimate partner violence, machismo, and marianismo. Journal

of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 24(4):341-54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jana.2013.01.009

Díaz, C., Rosas, M. & Gonzales, M. (2010). Escala de machismo

sexual (EMSSexismo-12). Summa Psicológica

UST, 7(2), 35-44. http://dx.doi.org/10.18774/448x.2010.7.121

Escobedo Portillo, María Teresa, Hernández Gómez, Jesús Andrés, Estebané Ortega, Virginia, & Martínez Moreno,

Guillermina. (2016). Structural

equation modeling: Features, phases, construction, implementation and results. Ciencia

& trabajo, 18(55), 16-22. https://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-24492016000100004

Etikan,

I., & Bala, K. (2017). Sampling and sampling methods [Muestreo y

Métodos de Muestreo]. Biometrics & Biostatistics

International Journal, 5(6), 215-217. https://doi.org/10.15406/bbij.2017.05.00149

Fondo de la Población de las Naciones Unidas. (2020). Tracking women’s decision-making for sexual

and reproductive health and reproductive rights.

https://www.unfpa.org/resources/tracking-womens-decision-making-sexual-and-reproductive-health-and-reproductive-rights

Glick, P. & Fiske, T. (1996). The Ambivalent

Sexism Inventory: Differentiating Hostile and Benevolent Sexism. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 70(3), 491-512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.3.491

Hernández-Sampieri, R. & Mendoza, C (2018). Metodología de la investigación: las rutas: cuantitativa y

cualitativa y mixta. México: Mc Graw

Hill- educación.

Herrera, D., Mamani, V., Arias, W.., & Rivera, R. (2019).

Análisis psicométrico de la Escala de Machismo Sexual en estudiantes

universitarios peruanos y chilenos. Revista de psicología (Santiago), 28(2),

64-74. https://dx.doi.org/10.5354/0719-0581.2019.55806

Huamani, J., Ojeda, E., Arias, W., Ceballos, F. & Calizaya, J.

(2023). Análisis psicométrico de la Escala de Machismo Sexual (EMS-Sexismo-12)

en estudiantes universitarios de Arequipa, Perú. Interacciones, 9, e301.

https://dx.doi.org/10.24016/2023.v9.301

Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática (2022). Perú:

Encuesta Demográfica y de Salud Familiar Endes 2022.

Instituto nacional de Estadística e Informática (25 de noviembre

del 2023). El 35,6% de mujeres de entre 15 y 49 años ha sido víctima de

violencia familiar en los últimos 12 meses [Nota de prensa]. https://m.inei.gob.pe/media/MenuRecursivo/noticias/nota-de-prensa-n-180-2023-inei.pdf

Instituto de estudio peruanos. (2023). Informe de Opinión –

Edición especial por el Día Internacional de la Eliminación de la violencia

contra la mujer. https://iep.org.pe/noticias/iep-informe-de-opinion-noviembre-2023-edicion-especial-25n/

Lai, K. (2020). Fit Difference Between Nonnested Models Given Categorical Data: Measures and

Estimation. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 28(1),

99–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2020.1763802

Lopes, F, Gomes, L., Veloso, V., Najda de Medeiros.,

& Florencio A. (2020). Escala de

Machismo Sexual. Evidências Psicométricas em Contexto

Brasileiro. Avaliaçao Psicologica

Interamerican Journal of Psychological Assessment. 19(4). 420-429. http://dx.doi.org/10.15689/ap.2020.1904.15892.08

Lloret-Segura, Susana, Ferreres-Traver,

Adoración, Hernández-Baeza, Ana, & Tomás-Marco, Inés. (2014). El Análisis

Factorial Exploratorio de los Ítems: una guía práctica, revisada y actualizada.

Anales de Psicología, 30(3), 1151-1169. http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.30.3.199361

Ministerio de la mujer y poblaciones vulnerables. (2024). Boletín

estadístico febrero 2024. https://portalestadistico.aurora.gob.pe/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/BV-Febrero-2024.pdf

Moya M, Expósito F. (2001). Nuevas formas, viejos intereses. Neosexismo en varones españoles. Psicothema.

13(4): 643-49.

Organización Panamericana de la Salud. (2029).

Masculinities and Health in the Region of the Americas. https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/51804

Sánchez, J. (2022). Análisis de las propiedades psicométricas de

la escala de machismo sexual (EMS-Sexismo - 12) en jóvenes de Lima

Metropolitana, 2022. [Tesis de pregrado, Universidad Cesar Vallejo].

Repositorio Institucional. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12692/109385

Silva, C. & Zavala A.( February

29, 2020). Sexual machism and Marianism in couple relations. A

bibliographical review.[ Congreso]. IV International

Congress of Research in Health Sciences and I International Seminar on

Nutrition and Food Safety.Ambato, Ecuador. Medwave,

20(1), 3. http://doi.org/10.5867/Medwave.2020.S1.CS06

Universidad Cesar Vallejo. (2020). Código de ética en

investigación de la Universidad Cesar Vallejo.

Whittaker, T. y Schumacker, R. (2022). A beginner’s

guide to Structural Equation Modeling. (5th ed). Routledge Taylor y Francis

Group

Xia, Y., & Yang, Y. (2019). RMSEA, CFI, and TLI in

structural equation modeling with ordered categorical data: The story they tell

depends on the estimation methods. Behavior Research Method, 51, 409 - 428. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-018-1055-2