http://dx.doi.org/10.24016/2024.v10.434

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Ten years of the Inventory

of Family Integration (IFI)

Diez años del Inventario de Integración Familiar (IIF)

Walter L Arias

Gallegos1*, Renzo Rivera1

1 Universidad

Católica San Pablo, Arequipa, Peru.

*

Correspondence: warias@ucsp.edu.pe

Received: May 05, 2024 |

Revised: November 29, 2024 | Accepted: December 20,

2024 | Published Online: December 30, 2024

CITE IT AS:

Arias

Gallegos, W., Rivera, R. (2024). Ten years of the Inventory of Family

Integration (IFI). Interacciones, 10, e434.

http://dx.doi.org/10.24016/2024.v10.434

ABSTRACT

Background: In Peru, various instruments have been validated to evaluate variables

associated with the family, but until recently there was no psychological test

aimed at evaluating the family that had been created in the country. This study

presents the psychometric development and applications of the Inventory of

Family Integration (IFI) after ten years of construction, and this being the

first and only instrument created in Peru that evaluates the family. Method: This

research is a theoretical study. Results: It starts first from the

review of the theoretical assumptions on which the instrument rests based on

the construct of family integration that is inspired

by the systemic family approach. Then, the studies carried out on the

psychometric properties of the IFI are presented in chronological order, from

its construction in 2013 to the recently published dyadic analysis in fathers

and mothers. Finally, the planning of future psychometric research with this

instrument is explained in a new stage of applied explorations in the field of

psychometrics and the family, both nationally and internationally. Conclusions:

The IFI has proven to be a robust and consistent instrument for assessing

family integration, but its psychometric properties still need to be evaluated

at national and international levels.

Keywords: Family integration, family

systemic approach, family, psychometrics.

RESUMEN

Antecedentes:

En Perú se han validado diversos instrumentos

para evaluar variables asociadas a la familia, pero hasta hace poco no existía

ninguna prueba psicológica orientada a la evaluación de la familia que haya

sido creada en el país. En el presente estudio se presenta el desarrollo

psicométrico y las aplicaciones del Inventario de Integración Familiar (IIF) a

sus diez años de construido, y siendo éste, el primer y único instrumento

creado en el Perú que evalúa la familia. Método: Está investigación es

un estudio teórico. Resultados: Se parte primero de la revisión de los

supuestos teóricos en los que reposa el instrumento en base al constructo de

integración familiar que se inspira en el enfoque familiar sistémico. Luego se

presentan en orden cronológico los estudios realizados sobre las propiedades

psicométricas del IIF, desde su construcción en el 2013 hasta el análisis

diádico en padres y madres recientemente publicado. Finalmente, se explica la

planificación de futuras investigaciones psicométricas con este instrumento en

una nueva etapa de exploraciones aplicadas en el campo de la psicometría y la

familia, tanto a nivel nacional como internacional. Conclusiones: El IIF

ha demostrado ser un instrumento robusto y consistente para evaluar la

integración familiar; pero aún así se deben de

evaluar sus propiedades psicométricas a nivel nacional e internacional.

Palabras claves: Integración familiar, enfoque sistémico familiar,

familia, psicometría.

In Peru, the

topic of the family has been constantly investigated from various disciplines,

from different approaches and through various methods. The Political

Constitution of Peru of 1993 as well as the Peruvian Civil Code protect the

family in various articles, not only promoting its protection and development,

but also recognizing the right of parents in making decisions regarding

education, care and upbringing of children, among other aspects (Torres et al.,

2023). Hence, different Peruvian universities, mainly, but not only, have

created research institutes specialized in the family.

Thus, for

example, the Institute for Marriage and

Family of the Universidad Católica San Pablo, in Arequipa, was created in

1998, beginning the work of psychological guidance and legal advice to the

population on family issues, until the year 2014 had a more academic

orientation with an emphasis on research, so that in 2016 the journal Perspectiva de Familia began to be published as a

dissemination organ of said institute (Arias et al., 2019). Another family

research center is the Family Institute

of the Universidad Femenina del Sagrado Corazón

(UNIFÉ), which has a markedly legal orientation, and which has existed since

2001, prior to the creation of the first Master's Degree in

Civil Law with a Mention in Family that was dictated in the country.

Likewise, since 2012 it has edited the journal Persona y Familia, one issue per year (Vidal, 2014). Thirdly, in

2005, the Institute for Family Sciences

was created at the Universidad de Piura, which promotes the publication of

books and studies on the family, and also offers the Master's

Degree in Marriage and Family (Corcuera, 2013). Fourthly, in 2008 the

Universidad Santo Toribio de Mogrovejo founded the Institute of Sciences for Marriage and Family, which also promotes

research on the family and various associated variables (Arias et al., 2022). All of these institutions are part of the Network of Latin American Family Institutes

(Red de Institutos Latinoamericanos

de Familia, REDIFAM), which was created in 2008, and which follows the

guidelines of the Catholic Church (Klaiber, 2016). Likewise, they organize

scientific research conferences on the family from the year 2010 (Castro, &

Arias, 2013).

In that sense, it has been, preferably, Catholic

universities that have promoted research on the family in the country, because

Peru has a strong religious identity and the Catholic

Church has issued various ecclesiastical documents that focus on the family.

from a traditional vision (Juan Pablo II, 1981). However, it is worth

mentioning that other non-Catholic institutions have made substantial

contributions to family research in Peru. For example, since 1994 the Peruvian

Institute of Psychological Guidance ( Instituto Peruano

de Orientación Psicológica,

IPOPS) was created, which provides psychological guidance to the population,

carries out training courses in psychological guidance and counseling, as well

as in family psychotherapy from a systemic approach, since it maintains links

inter-institutional meetings with the European and Latin American Network of

Systemic Schools (Red Europea y Latinoamericana de Escuelas

Sistémicas, RELATES). They have also published

several books on systemic family therapy (Villarreal-Huertas, &

Villarreal-Zegarra, 2016) and have edited since 2015 the journal Interacciones: Revista de Familia, Psicología Clínica y de la Salud, with a periodicity of three issues per year in the

continuous publication modality, which is indexed in various databases such as PsycINFO, Scielo, Redalyc, Dialnet, Doaj, Latindex, etc.

It can also be

said that the universities that have investigated the family the most in Peru,

from their respective Professional Schools of Psychology, have been Pontificia

Universidad Católica del Perú, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos,

Universidad de Lima, Universidad Nacional Federico Villareal, Universidad

Católica de Santa María, Universidad Católica San Pablo and Universidad Autónoma del Perú, among others. In this sense, the most

researched topics on the family in the country have addressed family

functionality (Galagarza, & Arias, 2017; Laurie

et al., 2018; Reusche, 1995; Villarreal-Zegarra, 2015); the impact of family in

education (Arias et al., 2016; Beltrán, 2013; Sotil, 2002); domestic violence (Arias et al., 2017; Delgado, 2016; Castro,

& Rivera, 2015; Castro et al., 2017; Miljánovich et al., 2010; Miljánovich et al., 2013); family and mental health

in children with respect to mood disorders, anxiety disorders, suicidal

ideation, antisocial behavior and psychoactive substance abuse (Araujo, 2005; Capa et al., 2010; Costa et al., 2020; Mallma, 2016; Mayorga, & Ñiquen,

2010; Pérez, 2016; Rivera et al., 2018; Rivera, & Cahuana, 2016; Rosas,

2014; Tirado et al., 2008; Yucra, 2016); femily and

well-being (Alarcón, 2014; Arias et al., 2014; Cárdenas, 2016; Caycho et al.,

2016; Pliego, & Castro, 2015); relationships between family, work and

economy (Arias et al., 2018; Castro et

al., 2013; Castro et al., 2016; Castro, Rivera, & Seperak,

2017; Muñoz, 2004; Prado, & Del Águila, 2010; Riesco, & Arela, 2015);

family structure (Chuquimajo, 2017; García, & Diez Canseco, 2019; Laguna, &

Rodríguez, 2008; Oporto, &

Zanabria, 2006; Prado, & Del

Águila, 2004; Silva, & Argote, 2007; Villarreal-Zegarra, &

Paz-Jesús, 2017), parenting styles and communication between parents and

children (Araujo, 2007, 2008; Muñoz, 2016; Reusche, 1999; Sobrino, 2008); marital

satisfaction (Dianderas, 2017; Núñez, 2018; Rebaza,

& Julca, 2009); social climate or family environment (Cruz, 2013; Matalinares et al., 2010; Oruna,

2016) and various psychological variables in families with children with

physical or mental disabilities (Cahuana et al., 2019; Cahuana et al., 2022;

Delgado, & Arias, 2022).

However,

despite this academic interest in family research in Peru, there are no

psychological tests created in the country; although various measurement

instruments that evaluate various variables associated with the family have

been validated. In this sense, in Peru various psychometric studies have been

carried out on various psychological tests that measure some family variables

such as the Family Satisfaction Scale

(Arias, Rivera, & Ceballos, 2018; Arias et al., 2019; Villarreal-Zegarra et

al., 2017), the Family Functionality

Scale (Bazo-Álvarez et al., 2016), the Steinberg

Parenting Styles Scale (Merino, & Arndt, 2004), the Parental Behavior Perception Inventory

(Merino et al., 2003; Merino et al., 2004), the Parenting Styles Scale (Matalinares et

al., 2014; Manrique et al., 2014), the Family

Interaction Quality Scale (Dominguez, & Alarcón, 2017; Dominguez et al.

, 2013), the APGAR-Family Scale

(Castilla et al., 2014), the Marital

Satisfaction Scale (Arias, & Rivera, 2018), the Satisfaction with Family Life Scale (Caycho-Rodríguez et al., 2018

) and the Work-Family Interaction

Questionnaire (SWING) (Chuquilin et al., 2021).

Considering

this absence of psychological tests created in the country that evaluate the

family, in 2012, two researchers from the city of Arequipa created the

Inventory of Family Integration (IFI from now on). Walter Arias, at that time a

psychologist by profession, Master in Educational Sciences

with a mention in Cognitive Psychopedagogy and

specialist in Psychological Counseling and Family Psychotherapy; and Rodolfo

Castro, at that time a Bachelor of Administration and a Master of Marriage and

Family Sciences from the Universidad Lateranense de

Roma. Both created the IFI from a theoretical vision that combines the systemic

approach and the Catholic perspective of the family. From 2013 to 2024, various

investigations have been published that have tested the psychometric properties

of this instrument, so this article briefly reviews the construction and

development process of the IFI and the results of the

research published in the span of approximately ten years. It is important to

mention this theorical review shows how the IFI was created and validated along the last ten years.

IFI

THEORETICAL FOUNDATIONS

The

IFI has been designed based on the theoretical principles of systemic family

therapy, considering the evolutionary cycles of the family, the family

structure, the different subsystems or family holons and the family dynamics

with respect to family limits and roles (Haley, 2002; Minuchin, & Fishman,

1996). Hence, the authors of this test defined family integration as “the

degree of health, balance and harmony of the relationships that arise from the

marital bond and that are naturally oriented to satisfy the needs of personal

transcendence based on respect, dialogue and the communion between its members

considering their responsibilities, and according to the life cycle of the

family” (Arias et al., 2013, p. 196, translated by the authors).

We will

briefly explain the principles of family therapy and the concepts on which the

IFI rests. Firstly, systemic family therapy began in the 1950s, especially with

the founding of the Mental Research

Institute in Palo Alto (California), in which various authors such as

Nathan Ackerman, Gregory Bateson, Donald Jackson and Paul Watzlawick, among

others; they apply the concepts of Bertalanffy's

(1976) general systems theory and Wiener's (1985) cybernetics postulates to

work with families, explaining how family interaction and communication

processes constitute the causal or triggering factors of mental pathology. Soon

these ideas and their corresponding practices were adapted by other therapists,

as happened with the Milan group led by Mara Selvini,

or the approaches of Maurizio Andolfi, who develops

an interactional approach (Andolfi, 1991) mediated by

cultural factors (Andolfi, 2009), or the narrative

approach developed by White and Epston (1990), among

others. In this way, several systemic schools are usually distinguished, such

as communication, relational, structural, strategic, etc.

With respect

to the principles from which the systemic family approach emanates, the family,

when considered as a system, must be seen as a totality in which the actions of

each of its members can influence the others or the entire system, hence, as

its members are connected, circular communication is established, and this

communication is also open, that is, it is influenced by the external

environment (Bertalanffy, 1976). Likewise, Watzlawick

(2014) explains that the axioms of communication applicable to the study of the

family are: first, that it is not possible not to communicate; second, the

relational and content levels of communication must be distinguished; third,

the family experience is lived individually; fourth, take into account both

verbal (digital) and non-verbal (analog) communication; and fifth, the

coexistence of symmetry and complementarity between its members.

On the other

hand, the family systemic conception suggests that

families can be considered as living systems that evolve and go through various

periods or stages over time. Although authors such as Habermas (1983, 1996)

have opposed “transplanting” concepts that emerged in the natural sciences to

the social sciences, or equating biological organisms with social systems,

because they operate with a different logic and their nature is

epistemologically different; from a systemic family approach, four evolutionary

periods are usually recognized in the family. These stages are determined by

each culture, which defines the roles and tasks of each stage (Arias, 2012). In

our culture, marked by a clear Western influence, four basic stages are

distinguished:

Couple

formation. Every family

system emerges as a vital marital unit, in which the contribution of each of

the members of the couple is combined with the pressures and influences that

will be exerted by both the respective families of origin and the sociocultural

environment in which they will develop (Ríos, 2005). In this first stage, the

couple must learn to relate, negotiate and communicate equitably and in a

concrete way, seeking at all times equality for both

the man and the woman (García-Méndez et al., 2010).

Family with

young children. A second

moment is given by the birth of the first child. The presence of a new member

in the family can destabilize the family order, however, if the first stage has

been overcome through the fulfillment of roles and functions defined for each

of the spouses; it is easier to adjust to the changes inherent in this stage by

following the guidelines for negotiating responsibilities with the newborn. As

children grow, parents face new and varied problems arising from parenting in

relation to the particularities of the child, at each stage of development

(Deater-Deckard, 2004). As for children, it is infancy and childhood, the

period in which children internalize the patterns of socialization and

coexistence that are experienced within the family and the spaces of school

life (Zevallos, & Chong, 2004).

Family with

teenage children. Adolescence

does not inherently represent a period of rebellion without cause or reason,

since a well-oriented adolescent who has begun a process of emotional growth

since childhood will continue to develop orderly and calmly during adolescence

(Bowen, 1998). It is necessary, however, that roles in the family be

redistributed, granting greater freedom to adolescent children to the same

extent that their responsibilities increase. It is a priority of upbringing and

parental action to consolidate the adolescent's identity, promote their

autonomy, respect their individuation, and support their independence;

allowing their emotional expression in balance with their responsible behavior.

All of this depends on the effective negotiation of roles in the family.

Family with

adult children. When children

grow up they inevitably leave home. Parents accustomed

to their presence do not always know how to deal with this new situation,

because frequently one of the children has been “triangulized,”

acting as a link between the parents (Minuchin, & Fishman, 1996). To

describe the absence of children, the metaphor of the “empty nest” is used

(Ríos, 2005), and although it is painful for parents to separate from their

children, according to the customs and values of each culture, it can also be

an opportunity for fulfillment of parents in their professional and marital

lives. Without having to worry about taking care of the children, the parents

have more time and have the experience and maturity necessary to embark on projects

that they left forgotten or that they postponed due to dedicating themselves to

their children.

In this scheme

of the life cycle, it must be kept in mind that the transition from one stage

to the other represents a period of crisis, but it contains within itself an

opportunity for the growth of the family (Ríos, 2005). It is also necessary to

highlight that in addition to the crisis that causes the transition from one

stage to another (evolutionary accidents of the family), multiple tragic events

can be identified in family history that are classified, following the

terminology of Thomas Holmes, as life events. stressors (Holmes, & Rahe,

1967). The wide variety of stressful life events includes divorce, migration,

death or loss of a family member, accidents, incurable illnesses, financial

crises or any other situation that shakes the stability of the structure and

functioning of the family; apart from the difficulties

inherent to the family life cycle. In this sense, Carter and McGoldrick (1989)

usually differentiate between four types of crises that families go through:

developmental crises correspond to the crises of evolutionary periods,

circumstantial crises would be analogous to the life events that arise from

external causes to the family, structural crises are associated with patterns

of dysfunctional relationships and communication between family members, and

crises of helplessness occur when a member of the family requires permanent

support because he or she depends on the other members for various reasons.

With respect

to family structure, this concept refers to the “link of social relationships

that determines the organization of family life. (…) In this framework, the

elements that define the family structure are the following: dynamics of

authority, normativity as a right, and degree of stability or transition”

(Castro et al., 2016, p. 89, translated by the authors). Likewise, based on the

family structure, four types of family are usually distinguished: the nuclear

or traditional family, which is made up of parents and children; single

parenthood is made up of only one parent and one or more children; the extended

or composite family, made up of two or more families, generally with ties of

blood, who cohabit in the same home; and the reconstructed family, in which,

for various reasons, a parent with or without his or her children forms a new

family with another person, who may also have children (Villarreal-Zegarra,

& Paz-Jesús, 2015). Although some authors suggest that we should not talk

about types of families (Guerra, 2004), or that on the contrary, nuclear

families should not be prioritized and other types of families should not be

pathologized (Chettiar, 2015); evidence suggests that nuclear family structure

is associated with greater physical health (Langton, & Berger, 2014; World

Family Map, 2014) and emotional well-being of children (Becker, 1987; Brown,

2004; Brown et al., 2015; Demo, & Acock, 1996; Merçe, 2015; Pearce et al., 2014), greater well-being and

mental health of parents (Burgos et al., 2014; Castro et al., 2016; Pliego,

& Castro, 2015), as well as with higher income and greater economic

stability (Huarcaya, 2011; Muñoz, 2004; Riesco, &

Arela, 2015) compared to single-parent families.

Now, the

family structure can also be considered as the “relational framework of

functional hierarchies determined by the roles played by the members of a

particular family” (Arias, 2012, p. 35). Thus, within each family system,

subsystems or holons can be distinguished made up of

levels of functioning that entail an inherent hierarchy in the order in which

they occur temporally and relationally (Minuchin, & Fishman, 1996). These

family subsystems or holons are:

The individual

holon is given by the individual contents that each member

of the family contributes. It includes the concept of self in the family

context and contains the personal and historical determinants of each individual, which are poured into the relational fabric

of the family; while, at the same time, specific interactions with others shape

and/or reinforce aspects of the individual personality of its members.

The marital

holon, specifically encompasses male-female relationships

between husband and wife. These are the exclusive responsibility of the couple

and children should not interfere in their parents' affairs. According to Bert

Hellinger (2002, 2005), the principle that determines harmony in the marital

holon is balance. Man and woman must be on the same level: both must give and

receive in the same measure for their relationship to prosper and last. Here,

marital satisfaction comes into play as a key construct that has allowed the

measurement of the marital subsystem (Arias, & Rivera, 2018).

The parental

holon is defined as the relational context that includes

interactions between parents and children. These have directly to do with the

upbringing and socialization of children (Manrique et al., 2014). This

subsystem changes as children grow, as their needs change, and their

possibilities for independence develop; so parents

must grant them more freedom while demanding more responsibility (Zevallos,

& Chong, 2004). Unlike the marital holon, in the parental holon there is

imbalance due to the nature of the relationship between parents and children,

since the parents are the ones who give and the

children always receive. Nothing a child does can repay what his parents have

done or do for him (Hellinger, 2005).

The fraternal

holon is determined by the relationships between siblings

and constitutes the most important subsystem for the socialization of the child

(Aldeas Infantiles, 2022). Children support each

other, attack each other, have fun, share their experiences, their moments and

thus learn from each other. The brothers are ordered in a temporal hierarchy

that goes from oldest to youngest, but despite this,

all brothers as children are at the same level. In the fraternal holon, trust

between brothers is fundamental. Just as the affairs of the parents are not the

concern of the children, there are things about the children that should not

leave the fraternal holon.

Between each

holon there are limits, determined by the rules and roles of the members that

compose them, whose function is to protect the differentiation of the

subsystem. For the harmonious integration of the family and the internalization

of functional forms of socialization, it is essential that each member takes

his place, locating himself in the subsystem and in the order that corresponds

to him to play his role as father, mother, older sister, or younger brother

(Minuchin, & Fishman, 1996). This will depend, however, on whether the

hierarchical ordering of its members is respected in the family, that

relationship rules are established and that the limits between family

subsystems are well differentiated. According to Minuchin (2003), if these

principles are ignored, intra-family relationships are altered, which results

in a distortion of social behavior patterns.

Another

important principle within the structure of the system is that of belonging to

the family. As has been proven by various authors such as Maslow (1968) and his

hierarchy of needs, or studies on conformism (Asch, 1964), people have the need

to feel that they belong to certain social groups, which can have some impact

on their behavior. Since the family is the most essential human group for the

development of the person, it is to be expected that similar rules come into

play as a web of conscious and unconscious motivations that move and are

installed in the core of the family structure.

All these

aspects are evaluated by the IFI from a systemic approach; hence the test has a

structure of five factors corresponding to each holon or family subsystem, and

within each one, aspects related to the roles and functions of each member of

the family are considered. the family according to its location within the

limits demarcated by each holon. With respect to the family perspective that is

based on Christian anthropology, it is neither contrary nor opposed to the

systemic approach, but first of all, it highlights the formation of the family

as a divine design, according to which, man is a being created by God for the

encounter with his fellow human beings and to live in communion (Caffarra,

2011), one of these spaces being the family, and the marital union; whose

purpose according to natural law is the procreation and education of children.

Hence, the family has a deeply theological meaning (Kasper, 1980), which is

safeguarded by the acatholic Church through various

ecclesiastical documents, papal encyclicals, and primarily, by the holy

scriptures (Diez Canseco, 2020). Secondly, the Catholic Church promotes a

traditional family structure, that is, nuclear, but is not opposed to other

forms of family organization, but instead suggest members of the Church to

strive to establish a nuclear family model, in as far as possible, where each

member also assumes their biologically and culturally determined roles and

functions (Melina, 2010). Likewise, thirdly, from the family perspective,

various family subsystems are also recognized, at the individual level (Tamés, 2011), at the marital level (Rodríguez, 2008, 2015;

Scola, 2001), at the parental level (Connolly, 2015; Palet,

2007) and at the fraternal level (Rodríguez, 2006); that remain open to their

relationships with other systems in different contexts in which the family

interacts, such as work (Kampowski, & Gallazzi, 2015) and social contexts (Perriaux,

2011), to mention a few. Hence, both approaches have similarities, facilitating

their complementarity, although they also present certain differences, since,

for example, from a Catholic perspective the excessive emphasis that systemic

therapy places on relationships rather than on content has been questioned

(Lego, 2010).

STUDIES

CARRIED OUT WITH THE IFI

It is on the

theoretical bases previously stated that the IFI was constructed, whose

psychometric processes and analysis of the results are presented below. First,

a chart of 64 items was generated that were distributed in five dimensions

corresponding to each of the holons or family subsystems: individual, marital,

parental, fraternal and family. The items were evaluated by three family expert

judges who gave them a score from 1 to 4 on a Likert scale, where the highest

score represents a favorable opinion. These values were analyzed using

Aiken's V test, obtaining scores above 0.7, therefore, all items were

considered valid since none were eliminated. Next, the items were arranged in a

response protocol to be filled out by the subjects who made up the sample on a

five-level Likert-type response scale from “Always” to “Never.” In this way,

the IFI was applied to 334 people who live in the city of Arequipa, considering

as inclusion criteria that they are heads of nuclear families (men or women),

over 18 years of age, who wish to participate voluntarily and who sign the

informed consent.

The

psychometric analysis followed the criteria of classical test theory, and

item-test correlations with values greater than 0.2 in most cases were

reported, but nine items were eliminated due to obtaining correlation

coefficients with lower scores. On the other hand, although the KMO score was

high (.922) and Bartlet's sphericity test was significant (p < .001), the

factor analysis performed showed four factors that explained 64.18% of the

total variance of the test, Likewise, three items that had factor loadings less

than 0.3 were eliminated. In the end, 52 items and only one dimension were

considered, since the first factor explained 29.48% of the variance (Burga,

2006). The reliability index was calculated using Cronbach's alpha test,

obtaining a score of .739.

Scales were

also obtained for their qualification with three levels: the low level is

between values of 94 to 200 and is located in a

range of 204 to 235, the high level of family integration takes scores from 237

to 260 (Arias et al., 2013). These results were published in 2013 in the

journal Avances en Psicología of the Universidad Femenina

del Sagrado Corazón. But based on these psychometric results, some studies were

carried out with different samples in the city of Arequipa. Firstly, the IFI

was applied to 844 people with different marital statuses, from 13 districts,

and it was found that 62.6% had a low level of family integration. Moreover,

the level of higher education, married marital status, and evangelical religion

were the sociodemographic variables that had greater predictive power on family

integration. This study was published in the Revista de Investigación of the Universidad

Católica San Pablo (Castro et al., 2013).

That same

year, a paper was also presented at the III

Congress of Scientific Research in Family reporting the descriptive results

of the previous study, emphasizing that married people obtained slightly higher

scores than cohabitants in family integration and that economic income, as well

as the degree of instruction are associated with family integration (Castro,

& Arias, 2013). In another study with a sample of 395 people from Arequipa,

it was reported that family integration is positively and significantly

correlated with happiness, understood as subjective well-being. Furthermore,

the number of children and satisfaction with life had predictive power on

family integration. This research was published in 2014 in the Revista de Psicología de

Arequipa published by the Colegio de Psicólogos

del Perú Consejo Regional Directivo III (Arias et

al., 2014).

In 2016, in an

organizational context, another study was carried out with a sample of workers

from a department store in Arequipa, in which married workers with children

were evaluated, finding that they had severe levels of burnout syndrome and a

medium level of family integration, in addition, family integration had a

cushioning effect on burnout syndrome, which allowed raising the levels of job

satisfaction of the evaluated workers. This research was published in the

journal Illustro

of the Universidad Católica San Pablo (Arias, & Ceballos, 2016). Also, in

an organizational context, another predictive type of research was carried out

in which a battery with various instruments that evaluated family and work

variables was applied, within the framework of the family-work conflict topic.

The results indicated that after the application of the IFI, the Family

Satisfaction Scale of Olson and Wilson, the Marital Satisfaction Scale of Pick

and Andrade, the Job Satisfaction Scale of Warr, Cook and Wall and the Maslach

Burnout Inventory in 213 workers from a private university; marital

satisfaction, family satisfaction and family integration are not only related

to each other, but also had a positive impact on job satisfaction, moderating

the effects of burnout syndrome in workers (Arias et al., 2018). These results

provided evidence of the convergent validity of the IFI by positively

correlating with marital satisfaction and family satisfaction,

and were published in the journal Perspectiva de Familia of the Universidad Católica San Pablo.

For the year

2019, new psychometric studies were carried out with the IFI, with the purpose

of determining its internal structure and reliability, in increasingly numerous

samples, and with the participation of psychologist Renzo Rivera, who is a

specialist in psychometrics and he works as a teacher

at the Universidad Católica San Pablo. In this sense, 420 married or cohabiting

people from Arequipa with at least two children were evaluated, and a new

exploratory factor analysis was carried out with the optimal implementation

method of parallel analysis, with which a four-factor structure was found that

explained 55.2% of the total variance of the test, and internal consistency

indices calculated using McDonald's Omega test were obtained, which fluctuated

between ω= .867 and ω= .932.

Likewise, the interfactor correlations were all

greater than .455 and less than .683. Likewise, item 24, which says “We respect

the decisions our children make,” was eliminated (Arias et al., 2019). In this

way, the four-factor structure was closer to our initial theoretical approaches

of five holons or family subsystems. The results of this research were

published in the journal Ciencias Psicológicas

of the Universidad de la República de Uruguay.

Next,

considering that the family structure has changed a lot in recent years, it was

decided to do a new psychometric study with the IFI, to determine its

psychometric properties in nuclear families with children and without children.

For this, 502 people were evaluated, 48.2% men and 58.1% women with an average

age of 40 years, and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was applied. Firstly, a

unidimensional structure was determined for the 17 items (corresponding to the

marital holon and the personal holon) that were used to measure family

integration in couples without children, and secondly, the internal structure

of four factors was corroborated in the nuclear families evaluated, with high

reliability indices that were calculated with the ordinal alpha test, whose

values fluctuated between .869 and .932; while the unidimensional version for

couples without children obtained a reliability index of .993. In both cases,

the goodness of fit indices were adequate, so it can

be said that the IFI can be used to evaluate nuclear families with and without

children. These results were published in 2022 in the Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios en Familia published by the Univeridad

de Caldas in Colombia (Arias et al., 2022).

This year, 2024, three new activities have been carried out, which close a

stage of evaluation of the psychometric properties of the IFI, and begin

another. Firstly, with data collected in a probabilistic sample from the city

of Arequipa of approximately 1,500 people with diverse family structures,

various instruments have been applied in order to analyze the convergent and

divergent validity of the IFI. Among the tests used, the Family Cohesion Scale

(FACES III), the Marital Communication Inventory, the Parenting Styles

Questionnaire and the Marital Instability Scale have been applied. Surely, in

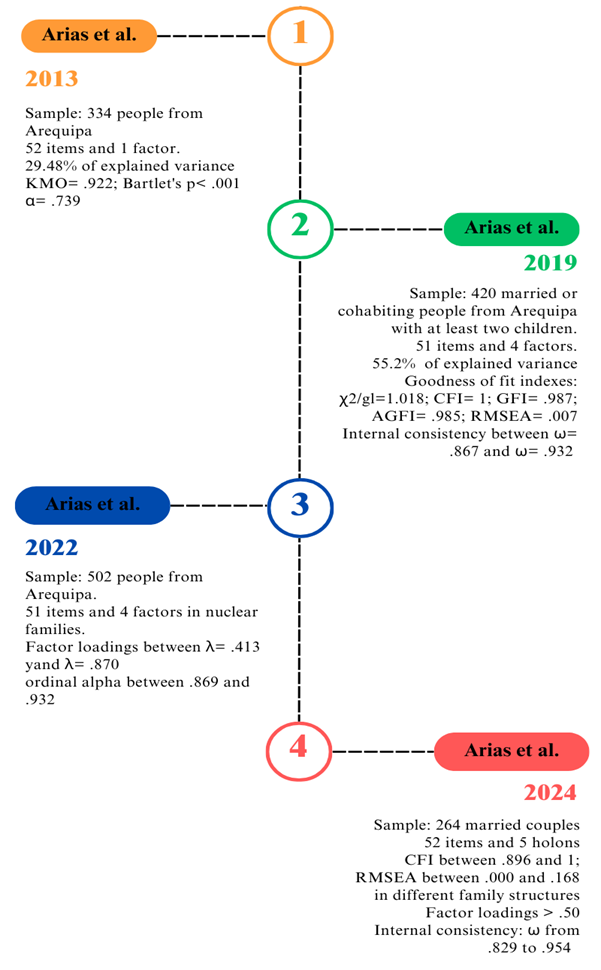

the coming months the results of this study will be obtained (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Change of

psychometric properties of IFI.

Secondly, a new study was published in which a dyadic analysis of the test

was carried out, depending on whether those tested are the father or the

mother. This analysis was carried out to determine if significant changes were

recorded in the responses of some or others, depending on gender differences

(García, & Nader, 2009) since various studies have reported that

differences could appear in the responses of the members of the couple in

aspects such as the assumption of their individual roles that is evaluated by

the personal holon (Bowen, 1998; Tamés, 2003), the perception of the couple’s

relationship that is evaluated by the marital holon (Eguiluz et al., 2012;

Villegas, & Mallor, 2012), parenting that is evaluated by the parental

holon (García, 2021; Pérez et al., 2021; Rodríguez et al., 2009;

Rodríguez-Sánchez et al., 2020; Santander et al., 2020), the attitudes towards

the relationships between siblings that are evaluated by the fraternal holon

(Aldeas Infantiles, 2022) and about their conceptions about the family, its

arrangements and dynamics inherent to it that are evaluated through of the

family holon (General Directorate of Childhood, 2022; Valdez et al., 2014).

The results of this research were published in 2024 in the journal Terapia

Psicológica de Chile. In this study, 264 married couples with nuclear families

who were purposively selected were assessed with the IFI. First, moderate

correlations were reported between the values of fathers and mothers in each

family holon: personal, marital, parental, fraternal and family. Secondly, the

dimensionality adjustment of each holon in fathers and mothers was adequate

with acceptable magnitudes through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Thirdly,

the reliability indices calculated with Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega

tests were between .784 and .942 in the first case, and .829 and .954 in the

second. Fourthly, an invariance analysis and a comparative analysis were

carried out between fathers and mothers, corroborating that the differences in

their responses were not significant (Arias et al., 2024).

Thirdly, the process has begun to adapt the IFI at the national level,

specifically in the cities of Arequipa, Cajamarca, Cusco, Huancayo, Ica,

Lambayeque, Trujillo, Lima, Puno, Ucayali, Tarapoto, and Tumbes; which include

the coast, mountain and jungle regions of the country, as well as the north,

center and south. In this way, through its application, it is intended to

establish at the national level, a standardized version, which allows us to

know its psychometric properties, such as validity, reliability and their

respective rating scales, in addition to others such as criterion validity and

factorial invariance. Likewise, one aspect that will be considered is

determining the internal structure of the test based on family composition,

that is, in nuclear families with children, nuclear families without children,

single-parent families and extended families at the national level. Finally, it

is also intended to analyze the scores obtained and analyze them based on

certain sociodemographic variables such as level of education, marital status,

number of children, etc.

DISCUSSION

In Peru, as in

many other Latin American countries, the topic of the family has been

extensively researched from various disciplines, approaches and theoretical

approaches (Arias, 2020; Jiménez-Torres et al., 2020; Rivera et al., 2023). As

previously stated, there are various lines of family research that have been

carried out, one of them being the evaluation of family variables or variables

associated with the family such as family satisfaction, family functionality,

work-family conflict, parenting styles, parenting styles, etc. However, to date

there are no tests created in Peru that evaluate family variables, since most of

them have been designed abroad and have only been validated in our country.

In

that sense, the IFI is a test designed and validated in Arequipa, a city

located in the south of Peru, which over ten years has been used in various

local or regional investigations, in which its psychometric properties have

been demonstrated. This article has presented its theoretical foundations and the results of the research carried out to

date with this instrument. Firstly, the test is based on the systemic family

approach, which, although it is known in Peru, has been very little studied,

since there is very little research based on systemic family therapy models.

Although there are some theoretical works that have disseminated the scope and

principles of this therapeutic approach (Arias, 2012; Sobrino, 1999;

Villarreal-Zegarra, & Paz-Jesús, 2015), and others of an empirical nature,

which have been based in Olson's circumplex model, which is, together with

McMaster's family functioning model and Beavers' systemic model, the most used

in family research from systemic approaches (Ortiz, 2008).

Likewise, the

empirical work on systemic approaches that has been carried out in Peru,

although it has generated important information regarding family functionality

and various psychosocial variables (Alarcón, 2014; Bazo-Álvarez et al., 2016;

Capa et al., 2010; Ferreíra, 2003; Mayorga, & Ñiquén, 2010), have only taken the circumplex model, with

the purpose of making psychometric adaptations of the Olson Family Satisfaction

Scale, or to assess family satisfaction with this scale, but without

necessarily sharing the theoretical assumptions of systemic family therapy.

Thus, the IFI can contribute to promoting and internalizing the systemic model

in the approach and evaluation of various family variables, which constitutes

another of its benefits.

On the other

hand, the results obtained in the latest psychometric studies of the IFI have

allowed us to corroborate its internal structure of five factors with adequate

reliability indices (Arias et al., 2022), even though the dyadic analysis of

the instrument, which allows us to assess whether the responses of fathers in

relation to those of mothers who belong to the same family nucleus can explain

possible differences with respect to the psychometric properties of the IFI.

The results obtained from said study lead us to affirm that, regardless of

whether the instrument is answered by fathers or mothers, it can offer us valid

and reliable measures in each of its dimensions or factors that evaluate family

holons, since the comparative analysis and factorial invariance showed scores

that suggest that there are no significant differences between the respondents

and therefore the IFI is not a biased instrument based on the sex of the

parents or their role in the family (Arias et al., 2024).

All the

results presented together suggest that the IFI is a test that has evidence of

validity and reliability, and therefore can be applied at the national level.

Precisely for this reason, a new stage of analysis of the psychometric

properties of this instrument has been undertaken, but considering samples from

all of Peru, in order to have a standardized version

of the IFI that can be used at the national level, and then also obtain

evidence of validity and reliability in other Latin American countries.

However, despite the theoretical, practical and psychometric benefits of the

IFI, a limitation is that it has been designed to evaluate nuclear families

with children, although in a previous study, its psychometric properties have

also been reported in married couples without children (Arias et al., 2022).

However, considering that in recent decades the structure of families has

changed, so that many couples no longer usually marry (Pearce et al., 2014;

Sigle-Rushton, & McLanahan, 2002) and have fewer and fewer children than in

the past (Espinoza, & Colil, 2015; Huarcaya, 2011; Merçe, 2015;

Mitchell et al., 2015; Pugliese, 2009), divorce rates have increased and

nuclear families have registered a decrease (Pinzón, & Vanegas, 2018; Tay-Karapas et al., 2020; Ullman et al., 2010), while

single-parent families have increased (Jociles, 2008;

Domínguez et al., 2019; Puello et al., 2014; Rodríguez, & Luengo, 2003;

Salvo, & Gonzálvez, 2015); it is necessary to

apply the instrument in samples with different family structures.

Therefore, in

the second stage of research into the properties of the IFI, it will not only

be applied to samples from several cities in Peru, but its psychometric

properties will also be assessed based on various family structures, that is,

single-parent families, extended and restructured families; analyzing whether

the marital, parental and fraternal holons replicate their internal structure

regardless of the type of family in question, or if they are related to

associated variables such as marital satisfaction (Arias, & Rivera, 2018;

García-Méndez et al., 2010; Eguiluz et al., 2012), parenting styles (Raimundi et al., 2017; Tur-Porcar

et al., 2015), etc. In addition, IFI results will be compared with instruments

created in other countries such as the Family

Adaptability and Cohesion Scale (FACES III), the Marital Communication

Inventory, the Parenting Styles Questionnaire and the Marital Instability

Scale. In conclusion, the IFI is the first test created in Peru to

evaluate the family, and it is also one of the few tests created in Peru that

has psychometric evidence sustained over time for just over ten years. We hope

that the next planned stages of research could

concrete as soon as possible.

ORCID

Walter

L Arias Gallegos https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4183-5093

Renzo

Rivera https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5897-9931

AUTHORS’

CONTRIBUTION

Walter

L Arias Gallegos: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Investigation,

Writing - Original Draft, Visualization.

Renzo

Rivera: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Writing -

Original Draft, Visualization.

FUNDING SOURCE

This study has not been funded by any institution.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no

conflicts of interest in collecting data, analyzing information, or writing the

manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Not applicable.

REVIEW PROCESS

This study has been reviewed by external

peers in double-blind mode. The editor in charge was Anthony Copez-Lonzoy. The review process is included as

supplementary material 1.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Not applicable.

DISCLAIMER

The authors are responsible for all statements made in this article.

REFERENCES

Alarcón, R.

(2014). Funcionamiento familiar y sus relaciones con la felicidad. Revista Peruana de Psicología y Trabajo

Social, 3(1), 61-74.

Aldeas

Infantiles (2022). Consejos para mejorar

la convivencia entre hermanos. SOS Children’s Villages.

Andolfi, M.

(1991). Terapia familiar: un enfoque

interaccional. Paidós.

Andolfi, M.

(2009). La psicoterapia como viaje transcultural. Psicoperspectivas, 8(1), 6-44.

Araujo,

D. (2005). La satisfacción familiar y su relación con la agresividad y las

estrategias de afrontamiento del estrés en adolescentes de Lima Metropolitana. Cultura, 19, 13-38.

Araujo,

D. (2007). Comunicación con los padres y factores de personalidad situacional

en adolescentes de Educación Superior. Cultura,

21, 13-30.

Araujo,

D. (2008). Comunicación padres-adolescente y estilos y estrategias de

afrontamiento del estrés en escolares adolescentes de Lima. Cultura, 22, 227-246.

Arias,

W. L. (2012). Algunas consideraciones sobre la familia y la crianza desde un

enfoque sistémico. Revista de Psicología

de Arequipa, 2(1), 32-46.

Arias,

W. L. (2020). Hacia una visión integral de la familia. En W. L. Arias (Ed.) Psicología y familia. Cinco enfoques sobre

familia y sus implicancias psicológicas (pp. 245-275). Adrus Editores.

Arias, W. L., Castro, R., Dominguez, S., Masías, M.,

Canales, F., Castilla, S., & Castilla, S. (2013). Construcción de un

inventario de integración familiar. Avances en Psicología, 21(2),

195-206. https://doi.org/10.33539/avpsicol.2013.v21n2.286

Arias, W. L., Castro, R., & Rivera, R. (2022).

Propiedades psicométricas del Inventario de Integración Familiar para parejas

con hijos y sin hijos de Arequipa. Revista

Latinoamericana de Estudios de Familia, 14(1),

92-116. https://doi.org/10.17151/rlef.2022.14.1.6

Arias, W. L., Castro, R., Rivera, R., & Ceballos, K.

(2019). Análisis factorial exploratorio del Inventario de Intregración Familiar

en una muestra de trabajadores de la ciudad de Arequipa. Ciencias Psicológicas, 13(2),

367-377. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v13i2.1893

Arias,

W. L., & Ceballos, K. D. (2016). Síndrome de burnout, satisfacción laboral

e integración familiar en trabajadores de una tienda por departamento de

Arequipa. Illustro,

7, 43-58.

Arias,

W. L., Ceballos, K. D., Román, A., Maquera, C., &

Sota, A. (2018). Impacto de la familia en el trabajo: Un estudio

predictivo en trabajadores de una universidad privada de Arequipa. Perspectiva de Familia, 3, 45-78.

Arias,

W., Dominguez, S., Gutiérrez-Cieza, V., Acosta-Loayza, A., & Clark, M.

(2024). Dyadic analysis of the

Inventory of Family Integration in fathers and mothers in the city of Arequipa. Terapia

Psicológica, 42(1),

1-27. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-48082024000100001

Arias, W., Galagarza, L. Y., Rivera, R., & Ceballos,

K. (2017). Análisis transgeneracional

de la violencia familiar a través de la técnica de genogramas. Revista

de Investigación en Psicología, 20(2),

283-308. http://dx.doi.org/10.15381/rinvp.v20i2.14042

Arias,

W. L., Masías, M. A., Salas, X., Yépez, L., & Justo, O. (2014). Integración

familiar y felicidad en la ciudad de Arequipa. Revista de Psicología de Arequipa, 4(2), 204-215.

Arias,

W. L., Quispe, A. C., & Ceballos, K. D. (2016). Estructura familiar y nivel

de logro de niños y niñas de escuelas públicas de

Arequipa. Perspectiva de Familia, 1, 35-62.

Arias,

W. L., & Rivera, R. (2018). Análisis psicométrico de la Escala de

Satisfacción Marital en trabajadores de una empresa privada de Arequipa (Perú).

Revista de Psicología (Universidad

Nacional de San Agustín), 2(1),

21-30.

Arias,

W. L., Rivera, R., & Ceballos, K. D. (2018). Análisis psicométrico de la

Escala de Satisfacción Familiar de Wilson y Olson en una muestra de

trabajadores de Arequipa. Ciencia &

Trabajo, 20(61), 56-60.

Arias,

W. L., Rivera, R., Laurie, P., & Ceballos, K. D. (2019). Propiedades

psicométricas de la Escala de Satisfacción Familiar de Olson y Wilson en

estudiantes universitarios. Perspectiva

de Familia, 4, 47-66.

Asch, S. E.

(1964). Psicología social. Eudeba.

Bazo-Álvarez,

J. C., Bazo-Álvarez, O. A., Aguila, J., Peralta, F., Mormontoy, W., & Bennett, I. M. (2016). Propiedades

psicométricas de la Escala de funcionalidad familiar FACES-III: un estudio en

adolescentes peruanos. Revista Peruana de

Medicina Experimental y Salud Pública, 33(3),

462-470.

Becker, G.

(1987). Tratado sobre la familia.

Alianza Editorial.

Beltrán,

A. (2013). El tiempo de la familia es un recurso escaso: ¿cómo afecta su

distribución en el desempeño escolar? Apuntes,

40(72), 117-156.

Bertalanffy,

L. (1976). Teoría general de los sistemas.

Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Bowen,

M. (1998). De la familia al individuo. Editorial Paidos.

Brown, S. L.

(2004). Family structure and child well-being: the significance of parental

cohabitation. Journal of Marriage and

Family, 66, 351-367.

Brown,

S. L., Manning, W. D., & Stykes, J. B. (2015).

Family structure and child well-being: Integrating family complexity. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77, 177-190. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12145

Burga, A.

(2006). La

unidimensionalidad de un instrumento de medición:

perspectiva factorial. Revista de

Psicología (Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú), 24(1), 53-80. https://doi.org/10.18800/psico.200601.003

Burgos, J. M.,

Dávalos, G., & Martínez, J. (2014). Psicología

de la familia: estructuras y trastornos. CEU Ediciones.

Caffarra, C. (2011). La

familia: Un lugar de la experiencia de comunión. Persona y Cultura, 9(9),

69-79.

Cahuana,

M., Arias, W. L., Rivera, R., & Ceballos, K. D. (2019). Influencia de la

familia sobre la resiliencia en personas con discapacidad física y sensorial de

Arequipa, Perú. Revista Chilena de

Neuropsiquiatría, 57(2), 118-128.

Cahuana,

M., Ramírez, M., & Aragón, P. B. (2022). Primera noticia y resiliencia

maternal en la discapacidad intelectual: Una revisión teórica. Revista de Psicología (Universidad Católica

San Pablo), 12(1), 49-66. https://doi.org/10.36901/psicologia.v12i1.1473

Capa,

W., Vallejos, M., & Cárdenas, R. (2010). Factores psicosociales y

demográficos asociados al consumo de drogas en adolescentes de una zona urbano popular de

Lima Metropolitana. Revista de

Investigaciones Psicológicas, 1,

21-37.

Cárdenas, M. V. (2016). Funcionamiento familiar, soporte social percibido y

afrontamiento del estrés como factores asociados al bienestar psicológico en

estudiantes de una universidad privada de Trujillo – La Libertad. Revista de Psicología (Universidad César

Vallejo), 18(1), 72-85.

Carter,

B., & McGoldrick, M. (1989). The family cycle. A framework for family therapy. Brunner & Mazale.

Castilla,

H., Caycho, T., Shimabukuro, M., & Valdivia, A. (2014). Percepción del

funcionamiento familiar: Análisis psicométrico de la escala APGAR-familiar en

adolescentes de Lima. Propósitos y

Representaciones, 2(1), 49-63. https://doi.org/10.20511/pyr2014.v2n1.53

Castro,

R., & Arias, W. L. (2013). Familia: Base estructural para un desarrollo

auténticamente humano. Una aproximación desde la estructura e integración

familiar. En III Congreso de

Investigación Científica en Familia (pp. 145-163). Red de Institutos

Latinoamericanos de Familia.

Castro,

R., Arias, W. L., Dominguez, S., Masías, F., Salas, W., Canales, F., &

Flores, A. (2013). Integración familiar y variables socioeconómicas en Arequipa

metropolitana. Revista de Investigación

(Universidad Católica San Pablo), 4, 35-65.

Castro, R., Cerellino,

L. P., & Rivera, R. (2017). Risk

factors of violence against women in Peru. Journal

of Family Violence, 32(8),

807-815. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-017-9929-0

Castro, R.,

Riesco, G., & Arela, R. (2016). ¿Familia y bienestar? Explorando la

relación entre estructura familiar y satisfacción con la vida personal de las

familias. Boletim da Academia Paulista de Psicologia, 36(90), 86-104.

Castro, R.,

& Rivera, R. (2015). Mapa de la

violencia contra la mujer: La importancia de la familia. Revista de Investigación, 6,

101-125.

Castro,

R., Rivera, R., & Seperak, R. (2017). Impacto de la composición familiar en los niveles de

pobreza de Perú. Cultura Hombre Sociedad,

27(2), 69-88.

Caycho, T., Contreras, K., & Merino, C. (2016).

Percepción de los estilos de crianza y felicidad en adolescentes y jóvenes de

Lima Metropolitana. Perspectiva de

Familia, 1, 11-22.

Caycho-Rodríguez, T., Ventura-León, J., Barboza-Palomino,

M., Reyes-Bosio, M., Arias, W. L., García, C., Cabrera-Orosco, I., Ayala, J.,

Morgado-Gallardo, K., & Huamani, J. C. (2018).

Validez e invarianza factorial por sexo de una medida breve de Satisfacción con

la Vida Familiar en escolares de Lima (Perú). Universitas Psychologica, 17(5),

1-17. https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.upsy17-5.vifm

Chettiar, T. (2015). Treating

marriage as “the sick entity”. History of

Psychology, 18(3), 270-282. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039523

Chuquilin, A. Y., Choqque, T. E.,

Arias, W. L., & Huamani, J. C. (2021). Análisis psicométrico dl

Cuestionario Interacción Trabajo-Familia (SWING) en trabajadores de una

Municipalidad Distrital de Haquira (Apurímac - Perú). Perspectiva de Familia, 6,

9-28.

Chuquimajo, S. (2017). Personalidad

y clima social familiar en adolescentes de familia nuclear, biparental y

monoparental. Revista de Investigación en

Psicología, 20(2), 347-362. http://dx.doi.org/10.15381/rinvp.v20i2.14045

Connolly, D. (2015). Relación Padre-Hijos. Paulinas.

Corcuera,

P. (2013). La familia como objeto de investigación científica. Universidad de Piura.

Costa,

M. F., Leiva, G., Arias, W. L., & Rivera, R. (2020). Autoestima y

sensibilidad a la ansiedad en niños de familias intactas y padres divorciados

con y sin ruptura conflictiva de Arequipa. Perspectiva

de Familia, 5, 23-51.

Cruz,

M. (2013). Clima social familiar y su relación con la madurez social del

niño(a) de 6 a 9 años. Revista de

Investigación en Psicología, 16(2),

157-179.

Deater-Deckard, K.

(2004). Parenting stress. Yale University

Press.

Delgado, E. N., & Arias, W. L.

(2021). Estilos de crianza en niños con trastorno del espectro autista (TEA)

que presentan conductas disruptivas: Estudio de casos durante la pandemia de

COVID-19. Cuadernos de Neuropsicología,

15(1), 96-102. https://doi.org/10.7714/CNPS/15.1.201

Delgado, P. (2016). Estrategias de

negociación en parejas violentas y no violentas en Arequipa. Perspectiva de Familia, 1,

23-33.

Demo,

D. H., & Acock, A. C. (1996). Family structure,

family process, and adolescent well-being. Journal of Research

on Adolescence, 6, 457-488.

Dianderas,

C. (2017). Relación del sexismo en la satisfacción marital en Arequipa

Metropolitana. Avances en Psicología,

25(2), 171-180.

Diez

Canseco, M. L. (2020). Perspectiva católica de la familia. En W. L. Arias

(Ed.), Psicología y familia. Cinco

enfoques sobre la familia y sus implicancias psicológicas (pp. 21-64).

Joshua V&E.

Dirección

General de Infancia (2022). Protocolo

Programa de familias colaboradoras. Junta de Andalucía.

Domínguez, C., González, D., Navarrete, D., & Zicavo, N. (2019). Parentalización

en familias monoparentales. Ciencias

Psicológicas, 13(2), 346-355. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v

Dominguez, S.,

& Alarcón, D. (2017). Análisis

estructural de la Escala de Calidad de Interacción Familiar en escolares de

Lima. Perspectiva

de Familia, 2, 9-26.

Dominguez, S.,

Aravena, S., Ramírez, F., & Yauri, C. (2013). Propiedades psicométricas de

la Escala de Calidad de Interacción Familiar en escolares de Lima. Revista de Psicología (Universidad César

Vallejo), 15(1), 55-77.

Eguiluz, L. L., Calvo, R. M., & De la Orta, D. (2012). Relación

entre la percepción de la satisfacción marital, sexual y la comunicación en

parejas. Revista Peruana de Psicología y

Trabajo Social, 1(1), 15-28.

Espinoza, M., & Colil, P. (2015). Hogares y bienestar: Análisis de cambios

en la estructura de los hogares (1990-2015). In Panorama Casen (pp. 1-11). Ministerio de Desarrollo Social.

Ferreíra, A. M. (2003). Sistema de interacción familiar

asociado a la autoestima de menores en situación de abandono moral y

prostitución. Revista de Investigación en

Psicología, 16(2), 58-80.

Galagarza,

L. Y., & Arias, W. L. (2017). Alexitimia y funcionalidad

familiar en estudiantes de ingeniería. Perspectiva

de Familia, 2, 27-44.

García, G., &

Diez Canseco, M. L. (2019). Influencia de la estructura

familiar y funcionalidad familiar en la resiliencia de adolescentes en

situación de pobreza. Perspectiva de

Familia, 4, 27-45.

García,

I., & Nader, F. (2009). Estereotipos masculinos en relación de pareja. Enseñanza e Investigación en Psicología,

14(1), 37-45.

García,

P. (2021). Coeducar en familia. Save

the Children.

García-Méndez,

M., Rivera-Aragón, S., Díaz-Loving, R., & Reyes-Lagunes, I. (2010). Vicisitudes

en la conformación e integración de la pareja: aciertos y desaciertos. In R.

Díaz-Loving & S. Rivera-Aragón (Comps.), Antología

psicosocial de la pareja. Clásicos y contemporáneos (pp. 269-303).

Porrúa.

Guerra, R.

(2004). ¿Familia o familias? Familia natural y funcionalidad social. Persona y Cultura, 3(3), 87-103.

Habermas,

J. (1983). La reconstrucción del

materialismo dialéctico. Taurus.

Habermas,

J. (1996). La lógica de las ciencias

sociales. Tecnos.

Haley,

J. (2002). Terapia para resolver problemas. Nuevas estrategias para

una terapia familiar eficaz. Amorrortu Editores.

Hellinger, B. (2002). Lograr el amor en la pareja. Herder.

Hellinger, B. (2005). Órdenes de amor. Herder

Holmes, T. H.,

& Rahe, R. H. (1967). The Social Readjustment Rating Scale. Journal of Psychosomatic

Research, 11,

213-218.

Huarcaya, G.

(2011). La familia peruana en el contexto global. Impacto de la estructura

familiar y la natalidad en la economía y el mercado. Mercurio Peruano, 524,

13-21.

Jiménez-Torres,

A. L., Maldonado, M., Rodríguez, J., & Santiago, A. M. (2022). Familias y

parejas: Análisis histórico de publicaciones desde la perspectiva del enfoque

sistémico relacional. Revista

Puertorriqueña de Psicología, 33(1),

94-113. https://doi.org/10.55611/resp.3301.07

Jociles, M. I., Rivas,

A. M., Moncó, B., Vollamil,

F., & Díaz, P. (2008). Una reflexión crítica sobre la monoparentalidad:

el caso de las madres solteras por elección. Portularia, 8(1), 265-274.

Juan Pablo II.

(1981). Familiaris Consortio. Epiconsa.

Kampowski, S., & Gallazzi, G. (Comps.). (2015). Familia y desarrollo sostenible.

Universidad Católica San Pablo.

Kasper, W. (1980). Teología del matrimonio cristiano. Sal Terrae.

Klaiber, J. (2016). Historia

de contemporánea de la Iglesia Católica en el Perú. Pontificia Universidad

Católica del Perú.

Laguna,

J. P., & Rodríguez, A. S. (2008). Comportamientos socioemocionales de

resiliencia en preescolares procedentes de hogares mono y biparentales. Revista de Psicología (Universidad Católica de Santa

María), 5, 52-65.

Langton, C. E., & Berger, L. M. (2011). Family

structure and adolescent physical health, behavior, and emotional well-being. Social Service Review, Sep, 323-357.

Laurie, P.,

Arias, W. L., & Castro, R. (2018). Satisfacción familiar y malestar

psicológico como predictores del rendimiento académico en estudiantes

universitarios de Arequipa. Revista de

Psicología (Universidad Católica de Santa María), 15, 19-36.

Mallma, N. (2016).

Relaciones intrafamiliares de dependencia emocional en estudiantes de

psicología de un centro de formación superior. Acta Psicológica Peruana, 1(1),

107-124.

Manrique, D. L., Ghesquière, P.,

& Van Leeuwen, K. (2014). Evaluation of Parental Behavior Scale

in Peruvian Context. Journal of Children

and Family Studies, 23(5),

885-894. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-013-9744-z

Maslow, A. H.

(1968). Toward a psychology of being.

Insight Book

Matalinares,

M., Arenas, C., Sotelo, L., Díaz, G., Dioses, A., Yaringaño, J., Murata, R.,

Pareja, C., & Tipacti, R. (2010). Clima familiar y agresividad en

estudiantes de secundaria de Lima Metropolitana. Revista de Investigación en Psicología, 13(1), 109-128.

Matalinares,

M., Raymundo, O., & Baca, D. (2014). Propiedades psicométricas de la Escala

de Estilos Parentales. Persona, 17, 95-121.

Mayorga. E.,

& Ñiquen, M. (2010). Satisfacción familiar y

expresión de la cólera-hostilidad en adolescentes escolares que presentan

conductas antisociales. Revista de Investigaciones Psicológicas, 1, 87-92.

Melina, L.

(2010). Por una cultura de la familia. El

lenguaje del amor. Universidad Católica San Pablo.

Merçe, M. (2015). Impact of family structure changes on child wellbeing. Balkan Social Science Review,

6, 109-137.

Merino,

C., & Arndt, S. (2004). Análisis factorial confirmatorio de la Escala de

Estilos de Crianza de Steinberg: validez preliminar de constructo. Revista de Psicología (Pontificia

Universidad Católica del Perú), 22(2), 187-214.

Merino,

C., Díaz, M., & Cohen, B. H. (2003). De los niños a los padres: El

Inventario de Percepción de Conductas Parentales. Persona, 6, 135-149.

Merino,

C., Díaz, M., & DeRoma, V. (2004). Validación del instrumento de conductas

parentales: un análisis factorial confirmatorio. Persona, 7, 145-162.

Miljánovich, M. A., Nolberto, V., Martina, M.,

Huerta, R. E., Torres, S., & Camones, F. (2010). Perú: Mapa de violencia

familiar, a nivel departamental, según la ENDES 2007-2008. Características e

implicancias. Revista de Investigación en

Psicología, 13(2), 191-205.

Miljánovich, M. A., Huerta, R. E., Campos, E.,

Torres, S., Vásquez, V. A., Vera, K., & Díaz, A. (2013). Violencia

familiar: modelos explicativos del proceso a través del estudio de casos. Revista de Investigación en Psicología, 16(1), 29-44.

Minuchin, S.

(2003). El arte de la terapia familiar.

Paidós.

Minuchin,

S., & Fishman, H. (1996). Técnicas

de terapia familiar. Paidós.

Mitchell, C.,

Brooks-Gunn, J., Garfinkel, I., McLanahan, S., Notterman,

D., & Hobcraft, J. (2015). Family structure

instability, genetic sensitivity, and child well-being. American Journal of Sociology, 120(4),

1195-1225.

Muñoz,

I. (2004). Pobreza, economía y familia en el Perú. Provincia, 12, 53-64.

Muñoz, Z. E.

(2016). Estilos de socialización parental y dependencia emocional en mujeres de

16 y 17 años de edad en instituciones educativas

nacionales de Lima, 2014. PsiqueMag, 4(1),

81-101.

Núñez, A. L.

(2018). Componentes del amor y la satisfacción marital en casados y

convivientes de Arequipa. Perspectiva de

Familia, 3, 79-98.

Oporto,

C., & Zanabria, L. (2006). Inteligencia emocional en hijos

de familias nucleares y monoparentales. Revista

de Psicología (Universidad Católica de Santa María), 3, 25-36.

Ortiz, D. (2008).

La terapia familiar sistémica.

Universidad Politécnica Salesiana.

Oruna, A. (2016).

Ambiente familiar y percepción de la autoeficacia en estudiantes de ciencias de

la salud de una universidad privada de Huacho. Acta Psicológica Peruana, 1(2),

325-352.

Palet, M. (2007).

La educación de las virtudes en la

familia. Ediciones Scire.

Pearce,

A., Hope, S. Lewis, H., & Law, C. (2014). Family structures and

socio-emotional wellbeing in the early years: a life course approach. Longitudinal and Life Course Studies, 5(3), 263-282.

Pérez, F.,

Ruiz, R., & Morales, L. (2021). Coparentalidad en construcción: Cómo

se coordinan las parejas con la llegada del primer hijo o hija. Psykhe, 30(2), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.7764/psykhe.2019.22225

Pérez, P. Z.

(2016). Funcionamiento familiar e ideación suicida en alumnos de 5to año de

educación secundaria del distrito de San Juan de Miraflores. PsiqueMag, 4(1), 81-93.

Perriaux, J. (2011). La

familia ante algunos desafíos de la realidad actual. Persona y Cultura. 9(9),

12-33.

Pinzón,

L. E., & Vanegas, G. (2018). Narrativas acerca de la comunicación, límites

y jerarquía en niños con padres separados. Interacciones,

4(2), 115-129. https://doi.org/10.24016/2018.v4n2.100

Pliego, F., & Castro, R. (2015).

Tipos de familia y bienestar de niños y

adultos. El debate cultural del siglo XXI en 13 países democráticos.

Universidad Católica San Pablo.

Prado,

R., & Del Águila, M. (2004). Estructura y funcionamiento familiar en

adolescentes resilientes. Teoría e

Investigación en Psicología, 13,

85-113.

Prado,

T. R., & Del Águila, M. (2010). Ajuste y satisfacción en parejas que

trabajan. Revista de Investigaciones

Psicológicas, 1(1), 38-52.

Puello, M.,

Silva, M. & Silva, A. (2014). Límites reglas, comunicación en familia

monoparental con hijos adolescentes. Diversitas.

Perspectivas en Psicología, 10(2),

225-246.

Pugliese, L. (2009). Como

enfrentar los cambios en las estructuras familiares. Experiencias, desafíos en

curso, resultados, evaluación. Comentarios

de Seguridad Social, 22, 135-140.

Raimundi, M. J., Molina, M. F., Leibovich, N., & Schmidt,

V. (2017). La comunicación entre padres e hijos: su influencia sobre el

disfrute y el flow adolescente. Revista de Psicología, 26(2),

1-14. https://doi.org/10.5354/0719-0581.2017.48150

Rebaza, R. P.,

& Julca, M. B. (2009). Satisfacción marital y ansiedad por concebir un hijo

en mujeres con diagnóstico de infertilidad. Revista

de Psicología (Universidad César Vallejo), 11, 79-96.

Reusche, R. M. (1995).

Estructura y funcionamiento familiar en un grupo de estudiantes de secundaria

de nivel socioeconómico medio con alto y bajo rendimiento escolar. Avances en Psicología, 3, 163-190.

Reusche, R. M. (1999). El afecto y la

autoridad familiar en adolescentes. Revista

Peruana de Psicología, 4(7-8),

193-182.

Riesco, R., & Arela, R. (2015). Impacto de la

estructura familiar en la satisfacción con los ingresos en los hogares urbanos

en Perú. Economía, 38(76), 51-76.

Ríos, J. A.

(2005). Los ciclos vitales de la familia

y la pareja. ¿Crisis u oportunidades? Editorial CCS.

Rivera, R.,

Arias-Gallegos, W. L., & Cahuana-Cuentas, M.

(2018). Perfil familiar de adolescentes con sintomatología depresiva en la

ciudad de Arequipa, Perú. Revista Chilena de Neuro-Psiquiatría, 56(2), 117-126.

Rivera, R.,

Arias, W. L., Castro, R., & Torres, A. L. (2023). Estudio bibliométrico de las revistas de família: um análisis

global de las revistas indexadas em Scopus. Revista

Latinoamericana de Estudios de Familia, 15(1), 13-44. https://doi.org/10.17151/rlef.2023.15.1.2

Rivera, R., & Cahuana, M.

(2016). Influencia de la familia sobre las conductas antisociales en

adolescentes de Arequipa-Perú. Actualidades

en Psicología, 30(120), 85-97. https://doi.org/10.15517/ap.v30i120.18814

Rodríguez, J. M.

(2006). Amor conyugal. Serie Familia

Hoy. Universidad Católica San Pablo.

Rodríguez, J. M.

(2008). Vida espiritual en el matrimonio.

Serie Familia Hoy. Universidad Católica San Pablo.

Rodríguez, J. M.

(2015). Vida sexual en el matrimonio.

Serie Familia Hoy. Universidad Católica San Pablo.

Rodríguez,

C., & Luengo, T. (2003). Un análisis del concepto de familia monoparental a

partir de una investigación sobre núcleos familiares monoparentales. Papers, 69, 59-82.

Rodríguez, M. A.,

Del Barrio, M. V., & Carrasco, M. A. (2009). ¿Cómo perciben los hijos la

crianza materna y paterna? Diferencias por edad y sexo. Escritos de Psicología, 2(2),

10-18.

Rodríguez-Sánchez,

F., Malagon, J. K., & Salinas-Quiroz, F. (2020). Significados de madres y

padres mexicanos del mismo género en torno a la crianza. Revista Iberoamericana de Psicología, 13(1), 33-44.

Rosas,

B. (2014). Percepción de los vínculos parentales y funcionamiento familiar en

sujetos drogodependientes. Un recurso a explorar en el proceso de

rehabilitación. PsiqueMag, 3(1), 81-101.

Salvo,

I., & Gonzálvez, H. (2015). Monoparentalidad

electivas en Chile: Emergencias, tensiones y perspectivas. Psicoperspectivas, 14(2), 40-50.

Santander, E.,

Berríos, L., Soto, P., & Avendaño, M. (2020). Preferencias parentales de

socialización valórica en el Chile contemporáneo: ¿cómo influyen la clase

social y la religión de los padres en la manera en que quieren criar a sus

hijos? Apuntes, 87, 65-86. https://doi.org/10.21678/apuntes.87.1027

Satir,

V. (1995). Psicoterapia familiar conjunta. México: Ediciones

científicas La Prensa Médica Mexicana.

Scola, A. (2001). Hombre-mujer. El misterio nupcial.

Universidad Católica San Pablo.

Sigle-Rushton, W., & McLanahan, S. (2002). The Living Arrangements of new Unmarried. Demography,

39(3), 415-433.

Silva,

C., & Argote, C. (2007). Actitudes hacia matrimonio y divorcio en jóvenes

procedentes de familias intactas y divididas. Revista de Psicología (Universidad Católica de Santa María), 4, 29-37.

Sobrino, L. (1999). Terapia

estratégica. Revista Peruana de

Psicología, 4(7-8), 51-62.

Sobrino, L.

(2008). Niveles de satisfacción familiar y de comunicación entre padres e

hijos. Avances en Psicología, 16(1), 109-137.

Sotil, A. (2002).

Influencia del clima familiar. Estrategias de aprendizaje e inteligencia

emocional en el rendimiento académico. Revista

de Investigación en Psicología, 5(1),

53-69.

Tamés, M. (2003). La

familia: el lugar de la persona. Ediciones Promesa.

Tay-Karapas, K.,

Guzmán-González, M., & Yárnoz-Yaben, S. (2020).

Evaluación de la adaptación al divorcio-separación: Propiedades psicométricas

del CAD-S en el contexto chileno. Psykhe, 29(2),

1-10. hppts://doi.org/10.7764/psykhe.29.2.1484

Tirado, P.,

Álvarez, V., Chávez, M., Holguín, S., Honorio, A., Moreno, M., Sánchez, N., Shimajuko, A. & Uribe, M. (2008). Satisfacción familiar

y salud mental en alumnos universitarios ingresantes. Revista de Psicología (Universidad César Vallejo), 10, 42-48.

Torres, A., Cerellino,

L., & Rivera, R. (2023). Female

Perception of Cohabitation and Marriage in Metropolitan Arequipa. Interacciones, 9, e270. https://doi.org/10.24016/2023.v9.270

Tur-Porcar,

A., Mestre, V., & Llorca, A. (2015). Parenting: Psychometric analysis of