http://dx.doi.org/10.24016/2024.v10.428

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Prevalence of domestic

violence among health center users: a retrospective longitudinal analysis

Prevalencia de la violencia doméstica entre usuarios de centros de

salud: un análisis retrospectivo longitudinal

Marjorie Cristel Fernandez-Mamani 1*,

Erika Rosmery Janampa-Calderon

1*, Isaac Alex Conde Rodriguez 1,

Julio Cjuno 2

1 School

of Psychology, Universidad

Peruana Unión, Lima, Peru.

2 Postgraduate

Unit of Psychology,

Universidad Peruana Unión, Lima, Peru

* Correspondence: rosmerycalderon.07@gmail.com; marjoriefernandez@upeu.edu.pe

Received: September 03, 2024 |

Revised: September 09, 2024 | Accepted: November 28,

2024 | Published Online: December 31, 2024

CITE IT AS:

Fernandez-Mamani, M., Janampa-Calderon,

E., Conde Rodriguez, I, & Cjuno J. (2024). Prevalence of domestic violence among health center

users: a retrospective longitudinal analysis. Interacciones,

10, e428. http://dx.doi.org/10.24016/2024.v10.428

ABSTRACT

Introduction: To determine the prevalence

of domestic violence among users of a health center through a retrospective

longitudinal analysis by age groups and gender. Methods: This is a

retrospective longitudinal study based on data obtained from a health center in

Pichari, Cusco, Peru. The sample obtained was 13,040

users of the Comprehensive Health Insurance (SIS) by non-probabilistic

sampling. The evaluation was carried out using the Domestic Violence Screening

Form (VIF) of the Ministry of Health (MINSA). Results: We found that children and older people have

higher survival rates regarding domestic violence, the cumulative risk of

domestic violence over time at different stages of development is highest in

adolescence, followed by the young stage. Likewise, the cumulative risk is

consistently higher for the female gender. Conclusions: Domestic violence presents

a higher risk in adolescents, young people, and women. These findings highlight

the urgent need to implement concrete measures to address this problem, such as

prevention programs, mental health education, and strengthening support and

care services for victims and their families.

Keywords: Domestic violence, stages

of development, prevalence.

RESUMEN

Introducción: Determinar la prevalencia de la violencia doméstica entre los usuarios

de un centro de salud mediante un análisis longitudinal retrospectivo por

grupos etarios y género. Métodos: Se trata de un estudio longitudinal

retrospectivo a partir de los datos obtenidos de un centro de salud de Pichari,

Cusco, Perú. La muestra obtenida fue de 13,040 usuarios del Seguro Integral de

Salud (SIS) por un muestreo no probabilístico. La evaluación se realizó

mediante la Ficha de Tamizaje de Violencia Intrafamiliar (VIF) del Ministerio

de Salud (MINSA). Resultados: Encontramos que los niños y personas

mayores presentan tasas de supervivencia más altas referente a la violencia

doméstica, el riesgo acumulado de violencia doméstica a lo largo del tiempo en

distintas etapas de desarrollo es más alto en la adolescencia, seguido por la

etapa joven. Asimismo, el riesgo acumulado es consistentemente mayor para el

género femenino. Conclusiones: La violencia doméstica presenta mayor

riesgo en adolescentes, jóvenes y en mujeres. Los Estos hallazgos destacan la

necesidad urgente de implementar medidas concretas para abordar esta

problemática, tales como programas de prevención, educación en salud mental y

el fortalecimiento de los servicios de apoyo y atención para las víctimas y sus

familias.

Palabras claves: Violencia intrafamiliar, etapas de desarrollo,

prevalencia.

INTRODUCTION

Domestic violence encompasses all forms of abuse, both physical and psychological, that occur within relationships among family members, either permanently or through stages such as violence, honeymoon, and tension within the family bond (Pardo et al., 2023). This includes various physical, psychological, economic, etc. types perpetrated by one family member against another Mayor & Salazar, 2019). Similarly, domestic violence is described as a set of abusive actions that take place within the family environment, characterized by a power imbalance among those involved, in which one person exercises authority and control over another. This is manifested through various behaviors that cause physical, psychological, or emotional harm to a family member (Rose et al., 2024). From the psychiatric theoretical model, it is argued that individuals who perpetrate violence against a family member may have a mental disorder (such as sadomasochism). However, the prevalence of domestic violence cases reported due to this factor is minimal ( García et al., 2015). On the other hand, the cultural theoretical model holds that the causes of family violence stem from factors such as socioeconomic status, the power structure in society and the family, economic tensions, as well as institutional and political violence. It is important to emphasize that although these elements are linked to the occurrence of domestic violence, none of them can individually provide a complete explanation of the issue (Junco-Guerrero et al., 2023).

Domestic violence is recognized as a public health issue in several countries (World Health Organization, 2024). Alarming rates of abuse within households are observed in Latin America (Organización Panamericana de la Salud, 2023). For instance, in Colombia, the figures exceed 90% of cases, excluding physical violence, which also shows significant percentages in public spaces (Orozco et al., 2020). Similarly, in Chile, 35.7% of the population has been a victim of domestic violence, including 37.2% experiencing psychological violence, 24.6% suffering from less severe physical violence, 15% facing severe physical violence, and 15.6% enduring sexual violence (Amézquita-Romero, 2014). In addition, Cuba has reported a prevalence rate of 63.4% among women aged 60 to 64, highlighting this demographic as the group with the highest incidence (Rodríguez et al., 2018).

In the Peruvian context, alarming rates of domestic violence have been recorded, particularly in the departments of Apurímac, with 82.7%, and Cusco, with 80.6%, standing out as the areas with the highest percentages (Instituto Nacional de Estadistica e Informatica, 2018). The most vulnerable members, such as women, reported that having a partner with high alcohol consumption was a risk factor for physical abuse, with 52% stating their husbands had physically assaulted them under the influence of alcohol (Flores, 2020). Another study conducted in the Cusco-Peru region revealed that women receiving care at the Centro de Emergencia Mujer in Paucartambo who experience violence within their family environment tend to develop significant emotional dependence on their aggressors (Asmat & Rojas, 2024).

Therefore, this research aimed to identify the prevalence of intrafamily violence among users of a health center in Cusco, Peru. The goal was to obtain crucial data to understand the underlying factors of this issue and, based on these findings, develop effective interventions that promote the mental health and emotional well-being of affected individuals and their families.

METHODS

Research

design and settings

This study

employs a quantitative approach with a non-experimental, longitudinal, and

retrospective design (Rothman & Greenland, 2018). For data

collection, the Epidemiological Record for VIF (+) cases was used, which

contains the records of users from the Pichari Health

Center who experience intrafamily violence and are under case monitoring in

coordination with associated entities such as the Centro de Emergencia

Mujer and the Family Police of the Pichari district. However, it is essential to note that the

records from the Multisectoral Epidemiological Form belong to the Pichari Health Center, as they pertain to users covered by

the SIS insurance.

Participants

The sample is

non-probabilistic and of an accidental type, comprising 13,040 users at the Pichari Health Center in the department of Cusco, Peru. The

data were sourced from the health center's database of users who received

outpatient care between January and July 2022. The data collected included

users of both sexes, including children, adolescents, young adults, adults, and

older adults.

Measures

For the

variable of domestic violence, data were collected using the screening tool to

identify cases of Intrafamily Violence (VIF [+]) developed by specialists from

the Ministry of Health of Peru (2017). This tool is part of the data collection

battery used in primary healthcare at Peruvian health centers. It demonstrated

statistical reliability with Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.897.

Additionally, the instrument was accepted as a protocol aimed at implementing

routine procedures for detecting any violence against women and the family

unit. It also guides healthcare personnel to provide appropriate care.

Furthermore,

specific covariates were collected, including age groups (i.e., children,

adolescents, young adults, adults, and older adults) and sex (female and male)

based on the requested database.

Data analysis

Initially, a

data cleaning process was performed. Once completed, the data was transferred

to a matrix in Microsoft Excel 2019. Longitudinal statistical analyses were

conducted using RStudio version 2024.09.1. The prevalence of intrafamily

violence over time, segmented by developmental stage and gender, was evaluated

using survival analysis techniques with the survival package, which allowed for

calculating cumulative hazard functions and survival rates. The survminer package was utilized to visualize survival curves

and facilitate their graphical interpretation. Longitudinal data were processed

to observe changes in prevalence over time, thus assessing the trend of

intrafamily violence, with 95% confidence intervals for the survival rates.

Ethical

Aspects

It is

essential to mention that the data were obtained from secondary databases of

primary healthcare services from the Ministry of Health without any information

that could identify the patients. Therefore, the data was anonymous and

confidential. Approval was also obtained from the Ethics Committee of

Universidad Peruana Unión, as documented in Report No. 2023-CE-FCS-UPeU-009.

RESULTS

Survival function by developmental stage

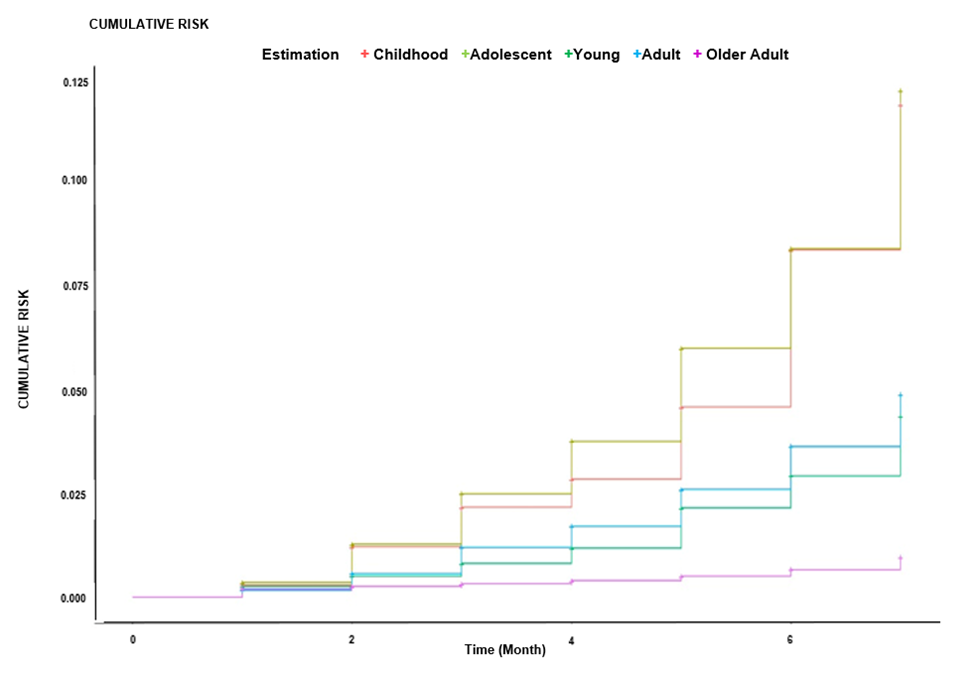

In Figure 1, it is observed that the cumulative risk of domestic

violence, which reflects the accumulation of risk factors over time at

different stages of development, is highest during adolescence, followed by the

young adult stage, with both reaching a cumulative risk higher than 0.10 by the

end of the study period. In contrast, the lowest cumulative risk is observed in

children and older adults, with values below 0.05, indicating lower cumulative

exposure to the risk of violence during these developmental stages. This

suggests a greater vulnerability over time for adolescents and young adults

than other age groups.

Figure 1. Cumulative risk of intrafamily violence by age group.

In Table 1, related to domestic violence, broken down by age groups

(children, adolescents, young adults, adults, and older adults) and months of

the year, the survival values represent the probability of not having

experienced a violent event, showing a progressive decrease in the following

months. For example, in the adolescent group, the survival rate drops from

0.996 in January (95% CI: [0.992 - 0.999], SE: 0.00182) to 0.873 in July (95%

CI: [0.843 - 0.904], SE: 0.01565), indicating an increase in the risk of

violence by mid-year. In the adult group, there is a decrease from 0.995 in

January (95% CI: [0.992 - 0.997], SE: 0.00126) to 0.86 in July (95% CI: [0.839

- 0.882], SE: 0.01099). Children and older adults have higher survival rates,

such as children with 0.998 in January (95% CI: [0.997 - 1.000], SE: 0.00068),

although this also decreases to 0.975 in July (95% CI: [0.966 - 0.985], SE:

0.004759). This trend suggests that exposure to domestic violence increases

towards the end of the evaluation period, especially among adolescents and

adults.

Table 1. Survival

analysis regarding intrafamily violence.

|

Month |

N |

VIF (+) |

Survival |

IC 95% |

SE |

|

Child |

|||||

|

January |

3888 |

7 |

0.998 |

[0.997 : 1.000] |

0.001 |

|

February |

3656 |

5 |

0.997 |

[0.995 : 0.999] |

0.001 |

|

March |

3262 |

5 |

0.995 |

[0.993 : 0.998] |

0.001 |

|

April |

2529 |

5 |

0.993 |

[0.991 : 0.996] |

0.001 |

|

May |

1832 |

5 |

0.991 |

[0.987 : 0.994] |

0.002 |

|

June |

1231 |

6 |

0.986 |

[0.980 : 0.991] |

0.003 |

|

July |

660 |

7 |

0.975 |

[0.966 : 0.985] |

0.005 |

|

Adolesscent |

|

|

|

|

|

|

January |

1227 |

5 |

0.996 |

[0.992 : 0.999] |

0.002 |

|

February |

2164 |

11 |

0.987 |

[0.980 : 0.993] |

0.003 |

|

March |

1070 |

13 |

0.975 |

[0.965 : 0.984] |

0.005 |

|

April |

907 |

11 |

0.963 |

[0.951 : 0.974] |

0.006 |

|

May |

695 |

14 |

0.943 |

[0.928 : 0.958] |

0.008 |

|

June |

528 |

15 |

0.917 |

[0.897 : 0.937] |

0.010 |

|

July |

251 |

12 |

0.873 |

[0.843 : 0.904] |

0.016 |

|

Young |

|

|

|

|

|

|

January |

3746 |

21 |

0.994 |

[0.992 : 0.997] |

0.001 |

|

February |

3394 |

34 |

0.984 |

[0.980 : 0.989] |

0.002 |

|

March |

3054 |

42 |

0.971 |

[0.965 : 0.977] |

0.003 |

|

April |

2396 |

36 |

0.956 |

[0.949 : 0.964] |

0.004 |

|

May |

1774 |

37 |

0.936 |

[0.927 : 0.946] |

0.005 |

|

June |

1222 |

36 |

0.909 |

[0.896 : 0.922] |

0.007 |

|

July |

727 |

39 |

0.86 |

[0.841 : 0.879] |

0.010 |

|

Adult |

|

|

|

|

|

|

January |

3362 |

18 |

0.995 |

[0.992 : 0.997] |

0.001 |

|

February |

3154 |

30 |

0.985 |

[0.981 : 0.989] |

0.002 |

|

March |

2840 |

34 |

0.973 |

[0.968 : 0.979] |

0.003 |

|

April |

2271 |

31 |

0.96 |

[0.953 : 0.967] |

0.004 |

|

May |

1705 |

34 |

0.941 |

[0.931 : 0.951] |

0.005 |

|

June |

1022 |

33 |

0.911 |

[0.897 : 0.924] |

0.007 |

|

July |

563 |

31 |

0.86 |

[0.839 : 0.882] |

0.011 |

|

Elderly

person |

|||||

|

January |

814 |

2 |

0.998 |

[0.994 : 1.000] |

0.002 |

|

February |

781 |

3 |

0.994 |

[0.988 : 0.999] |

0.003 |

|

March |

678 |

3 |

0.989 |

[0.982 : 0.997] |

0.004 |

|

April |

556 |

1 |

0.988 |

[0.979 : 0.996] |

0.004 |

|

May |

416 |

7 |

0.971 |

[0.956 : 0.986] |

0.007 |

|

June |

253 |

4 |

0.956 |

[0.935 : 0.977] |

0.011 |

|

July |

134 |

3 |

0.934 |

[0.903 : 0.966] |

0.016 |

Note: 95% CI

= 95% Confidence Interval; SE = Standard error of the survival rate; VIF =

Intrafamily Violence.

Survival function by gender

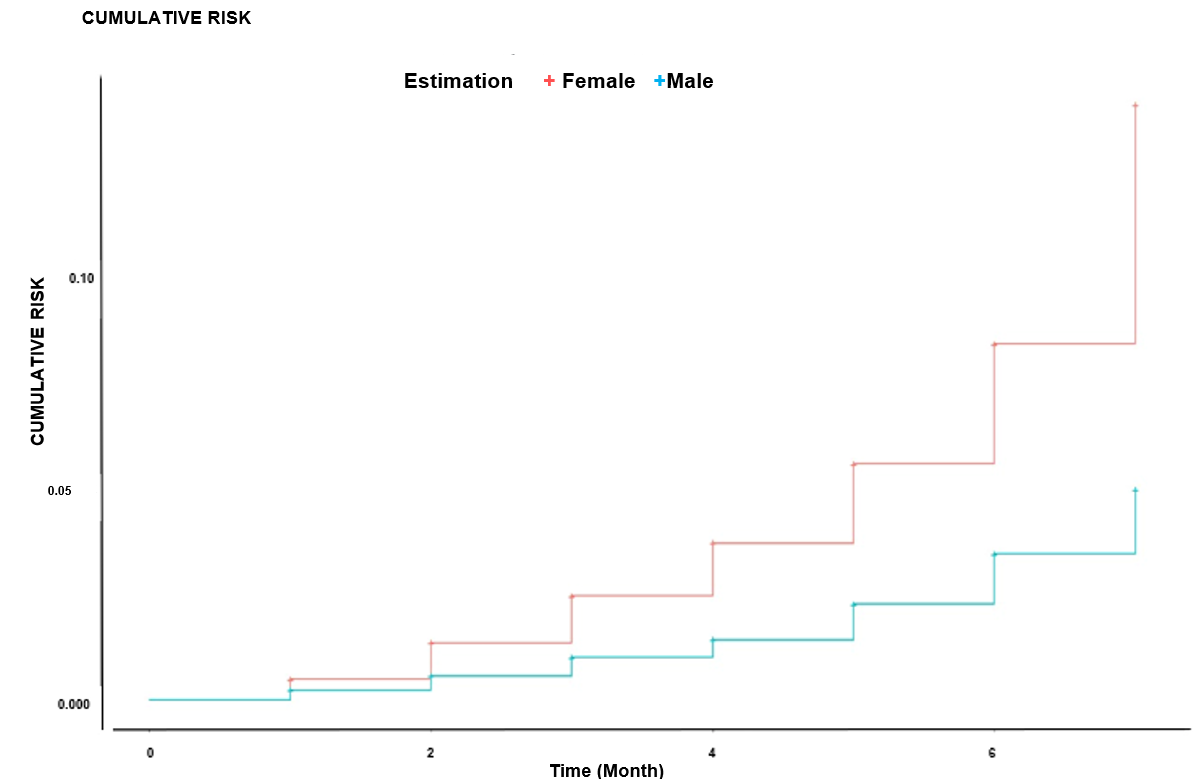

In Figure 2, the cumulative risk of domestic violence over time is

shown, broken down by gender. Throughout the months, the cumulative risk is

consistently higher for females, reaching a value above 0.10 by the end of the

period. In comparison, the cumulative risk for males remains lower, around

0.05, within the same time frame. This difference suggests a higher cumulative

vulnerability to intrafamily violence in females compared to males throughout

the study period.

Figure 2. Survival functions by gender.

In Table 2, the survival analysis in the context of intrafamily violence

is shown, broken down by gender and month. It can be observed that, in general,

women have a lower survival rate compared to men, indicating greater exposure

to the risk of violence. For example, in July, the survival rate for women is

0.871 (95% CI: [0.858 - 0.884], SE: 0.006660), while for men it is 0.952 (95%

CI: [0.941 - 0.963], SE: 0.005534). This difference suggests a higher

accumulated vulnerability in women by mid-year and towards the end of the year.

In earlier months, such as January, survival rates are high for both genders,

with 0.995 for women (95% CI: [0.994 - 0.997], SE: 0.000726) and 0.998 for men

(95% CI: [0.996 - 0.999], SE: 0.000765), reflecting a lower risk during that

period. Additionally, the number of intrafamily violence (VIF) cases is

consistently higher in women, as in March, where 83 cases were recorded in

women compared to 17 in men, which supports the higher accumulated risk

observed in women.

Table 2. Survival

Analysis of Intrafamily Violence by Gender

|

Month |

Sex |

N |

VIF (+) |

Survival |

IC 95% |

SE |

|

January |

Female |

9118 |

44 |

0.995 |

[0.994 : 0.997] |

0.001 |

|

Male |

3919 |

9 |

0.998 |

[0.996 : 0.999] |

0.001 |

|

|

February |

Female |

8495 |

71 |

0.987 |

[0.984 : 0.989] |

0.001 |

|

Male |

3654 |

12 |

0.994 |

[0.992 : 0.997] |

0.001 |

|

|

March |

Female |

7602 |

83 |

0.976 |

[0.973 : 0.979] |

0.002 |

|

Male |

3302 |

14 |

0.990 |

[0.987 : 0.993] |

0.002 |

|

|

April |

Female |

5973 |

73 |

0.964 |

[0.960 : 0.968] |

0.002 |

|

Male |

2686 |

11 |

0.986 |

[0.982 : 0.990] |

0.002 |

|

|

May |

Female |

4377 |

80 |

0.947 |

[0.941 : 0.952] |

0.003 |

|

Male |

2045 |

17 |

0.978 |

[0.972 : 0.984] |

0.003 |

|

|

June |

Female |

2795 |

77 |

0.920 |

[0.913 : 0.928] |

0.004 |

|

Male |

1461 |

17 |

0.967 |

[0.959 : 0.974] |

0.004 |

|

|

July |

Female |

1462 |

79 |

0.871 |

[0.958 : 0.884] |

0.007 |

|

Male |

873 |

13 |

0.952 |

[0.941 : 0.963] |

0.006 |

Note: 95% CI

= 95% Confidence Interval; SE = Standard error of the survival rate; VIF =

Intrafamily Violence.

DISCUSSION

This research aimed to identify the prevalence of Intrafamily Violence among the users of the Pichari Health Center, located in the department of Cusco. In this regard, we found a higher accumulated prevalence in children, adolescents, and women; additionally, women reported 6 times more cases of intrafamily violence (VIF) than men in all months, while in men, VIF was present in one reported case for every 120 records.

We found a higher accumulated probability that children and adolescents were victims of intrafamily violence. This result is like reports in Peru from the National Survey of Social Relations of Peru – ENARES, which indicated that more than 80% of children and adolescents have been victims of physical and/or psychological violence in their homes and/or schools (Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática, 2019). Another study conducted in Brazil with 551 participants reported that the prevalence of domestic violence, such as neglect (33.9%) and sexual abuse (31.9%) in children aged 5 to 10 years, was significant (Porto et al., 2012). These findings are concerning because living in households with intrafamily violence is a risk factor for emotional, physical, and sexual abuse, for developing emotional and behavioral problems, and for increased exposure to other adversities in their lives (Holt et al., 2008). This is an unresolved issue in our country, even though the well-being and health of children and adolescents are considered a fundamental right, and each state must ensure a healthy life and promote well-being at all ages (Ross et al., 2020). Promoting healthy, violence-free family relationships is an ongoing task that could be addressed through the implementation of more community-based mental health centers.

The women studied had a higher accumulated probability of experiencing intrafamily violence compared to men. In this regard, various reports show similar findings, such as the one conducted in the United States, which found that one in every woman was a victim of domestic violence, including economic, physical, sexual, or psychological abuse (Huecker et al., 2023), in Uruguay, a 2019 report stated that one in five women reported being a victim of violence by their partner in the past 12 months (United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund, 2019); Meanwhile, a 2024 global report by the World Health Organization indicated that one in three women were subjected to physical or sexual violence by their partner, with the highest rates occurring between the ages of 15 and 49 (World Health Organization, 2024b). These findings confirm that intrafamily violence is a phenomenon that transcends cultures and economic levels, and its statistics are alarming. Intrafamily violence is a phenomenon that transcends cultures and economic levels and can be explained through the theory of the cycle of violence (Walker, 1979), which describes a cyclical pattern of tension buildup, episodes of violence, and reconciliation that can manifest in any cultural, social, and economic context. On the other hand, the social ecology theory posits that multiple levels of the social environment, from direct family relationships to cultural norms, influence human behavior and can perpetuate violence, asserting that intrafamily violence is influenced by power dynamics and contextual factors that are universal, thus explaining its presence across various cultures and economic levels (Urie Bronfenbrenner, 1979).

On average, women reported up to six times more cases of intrafamily violence than men in all months. While no studies have reported the same proportion, some studies have reported somewhat similar results, such as the report from the United Kingdom, where 6.9% of women and 3.0% of men reported being victims of domestic violence, showing that the proportion of women victims of violence is double that of men (Office for National Statistics, 2022), similarly, in the United States, twice the proportion of women (e.g., 1 in 4 women and 1 in 9 men) were victims of domestic violence (Huecker et al., 2023). The higher prevalence of intrafamily violence victims among women in our study, compared to prevalence rates in developed countries like the United Kingdom and the United States, could be attributed to factors such as gender inequality, cultural acceptance of violence as a means of conflict resolution (Sardinha & Catalán, 2018) and higher levels of poverty and unemployment, which increase stress and conflict within the home (Mannell et al., 2022), This finding suggests the implementation of public policies to reduce intrafamily violence, mainly based on poverty and unemployment levels among women.

For every 120 individuals screened with the IPV tool, one case of intrafamily violence directed at males was reported. Although the prevalence is lower than that in women, studies have reported that the prevalence of domestic violence against men varies by country and culture, with reported rates ranging(Kolbe & Büttner, 2020) from 3.4% to 20.3%, with psychological violence being more common than physical violence among men . Risk factors for men becoming victims of intrafamily violence include their reluctance to identify their experiences with terms such as "domestic violence victim" due to traditional masculinity norms and associated stigmas. Other factors include the lack of support services specifically for men, their devotion to their families, fear of being judged by others (Moore, 2021), and inadequate responses from the police and judicial system when reporting incidents (Huntley et al., 2020). Therefore, in the Peruvian context, it is necessary to implement specialized centers for the care of intrafamily violence cases directed toward men.

Limitations

This study has certain limitations that should be considered when

interpreting the results. Firstly, the sample used was non-probabilistic and

accidental, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other

populations. It is also essential to consider that the IPV Screening Form used,

while reliable, may not capture all forms of intrafamily violence, especially

those that are not reported by the victims.

Conclusions and recommendations

Intimate partner violence in the district of Pichari,

La Convención province, Cusco department, Peru, shows

a higher cumulative prevalence in children, adolescents, and women.

Additionally, women experienced IPV six times more frequently than men in all

months, while in men, IPV was reported once in every 120 records. These

findings highlight the urgent need to implement evidence-based preventive

interventions to reduce the incidence of intimate partner violence.

Furthermore, future studies could implement interventions aimed at decreasing

domestic violence.

ORCID

Marjorie Cristel Fernandez Mamani: https://orcid.org/0009-0005-9593-3157

Erika Rosmery Janampa Calderon: https://orcid.org/0009-0006-5464-7426

Isaac Alex Conde Rodriguez: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5683-8596

Julio Cjuno: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6732-0381

AUTHORS’

CONTRIBUTION

Marjorie Cristel Fernandez Mamani:

Conceptualization, investigation, writing, review, supervision, and approval of

the final version.

Erika Rosmery Janampa

Calderon: Conceptualization, investigation, writing, review, supervision, and

approval of the final version.

Isaac Alex Conde Rodriguez:

Conceptualization, investigation, writing, and approval of the final version.

Julio Cjuno:

Conceptualization, investigation, writing, review, supervision, and approval of

the final version.

FUNDING SOURCE

Self-financed by researchers.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there were no conflicts of

interest in collecting data, analyzing information, or writing the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Not applicable.

REVIEW PROCESS

This study has been reviewed by external peers in double-blind mode.

The editor in charge was Renzo Rivera. The review process is included as

supplementary material 1.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The database is accessible at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14606663

DISCLAIMER

The authors are responsible for all statements made in

this article.

REFERENCES

Amézquita-Romero, G. A. (2014). Violencia intrafamiliar : mecanismos e instrumentos internacionales. Novum Jus, 8(2), 55–77.

https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.14718/NovumJus.2014.8.2.3

Asmat, M. A., & Rojas, D. D. (2024). Violencia

intrafamiliar y dependencia emocional en mujeres atendidas en el CEM de la

provincia de Paucartambo - Cusco-2023 [Tesis de pregrado, Universidad

Cesar Vallejo]. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12692/134477

Flores, J. J. (2020). Aportes teóricos a la violencia

intrafamiliar. Cultura, 34, 179–198.

https://doi.org/10.24265/cultura.2020.v34.13

García, M. J., Matud Aznar, M.

P., García Oramas, M. J., & Matud Aznar, M. P.

(2015). Salud mental en mujeres maltratadas por su pareja. Un estudio con

muestras de México y España. Salud Mental, 38(5),

321–327. https://doi.org/10.17711/SM.0185-3325.2015.044

Holt, S., Buckley, H., &

Whelan, S. (2008). The impact of exposure to domestic violence on children and

young people: A review of the literature. Child Abuse & Neglect, 32(8),

797–810. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CHIABU.2008.02.004

Huecker, M. R., King, K. C.,

Jordan, G. A., & Smock, W. (2023). Domestic Violence. In StatPearls. StatPearls

Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499891/

Huntley, A. L., Szilassy, E.,

Potter, L., Malpass, A., Williamson, E., & Feder, G. (2020). Help seeking

by male victims of domestic violence and abuse: an example of an integrated

mixed methods synthesis of systematic review evidence defining methodological

terms. BMC Health Services Research, 20(1), 1–17.

https://doi.org/10.1186/S12913-020-05931-X/FIGURES/2

Instituto Nacional de Estadistica

e Informatica. (2018). INEI difunde Base de Datos

de los Censos Nacionales 2017 y el Perfil Sociodemográfico del Perú.

https://m.inei.gob.pe/prensa/noticias/inei-difunde-base-de-datos-de-los-censos-nacionales-2017-y-el-perfil-sociodemografico-del-peru-10935/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática. (2019). INEI

presentó resultados de la Encuesta Nacional sobre Relaciones Sociales 2019.

https://www.gob.pe/institucion/inei/noticias/535040-inei-presento-resultados-de-la-encuesta-nacional-sobre-relaciones-sociales-2019

Junco-Guerrero, M., Fernández-Baena, F. J., &

Cantón-Cortés, D. (2023). Risk

Factors for Child-to-Parent Violence: A Scoping Review. Journal of Family

Violence, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10896-023-00621-8/TABLES/2

Kolbe, V., & Büttner, A.

(2020). Domestic Violence Against Men—Prevalence and Risk Factors. Deutsches Ärzteblatt

International, 117(31–32), 534.

https://doi.org/10.3238/ARZTEBL.2020.0534

Mannell, J., Lowe, H., Brown, L.,

Mukerji, R., Devakumar, D., Gram, L., Jansen, H. A. F. M., Minckas,

N., Osrin, D., Prost, A., Shannon, G., & Vyas,

S. (2022). Risk factors for violence against women in high-prevalence

settings: a mixed-methods systematic review and meta-synthesis. BMJ Global

Health, 7(3), 7704. https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJGH-2021-007704

Mayor, S., & Salazar, C.

(2019). La violencia intrafamiliar. Un

problema de salud actual. Gaceta Médica Espirituana, 21(1), 96.

http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?pid=S1608-89212019000100096&script=sci_arttext&tlng=en

Moore, T. (2021). Suggestions to

improve outcomes for male victims of domestic abuse: a review of the

literature. SN Social Sciences, 1(10), 1–18.

https://doi.org/10.1007/S43545-021-00263-X/METRICS

Office for National Statistics.

(2022). Domestic abuse victim characteristics, England and Wales - Office

for National Statistics.

https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/articles/domesticabusevictimcharacteristicsenglandandwales/yearendingmarch2022

Organización Panamericana de la Salud. (2023). Violencia

contra la mujer.

https://www.paho.org/es/temas/violencia-contra-mujer?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Orozco, K., Jiménez, L. K., & Cudris-Torres,

L. (2020). Mujeres víctimas de violencia intrafamiliar en el norte de

Colombia. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, 26(2), 56–68.

https://doi.org/10.31876/RCS.V26I2.32422

Pardo, D., Xan, C., Terry, J., & Neimanis,

A. (2023). Introduction: Domestication of War

- ProQuest. Catalyst : Feminism, Theory,

Technoscience, 9(1), 34–49. 10.28968/cftt.v9i1.39531

Porto, M., Carvalho. Jasintho,

Marchi, M., Guglielminetti, R., & Barbieri, D.

(2012). Domestic violence against children and adolescents: a challenge. Revista Da Associação Médica Brasileira (English Edition), 58(4),

465–471. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2255-4823(12)70230-8

Rodríguez, M., Gómez, C., Guevara, T., Arribas, A., Duarte,

Y., & Ruiz, P. (2018). Violencia intrafamiliar en el adulto mayor. Revista

Archivo Médico de Camagüey, 2, 204–213.

http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?pid=S1025-02552018000200010&script=sci_arttext&tlng=en

Rose, E., Mertens, C., & Balint,

J. (2024). Structural Problems Demand Structural Solutions: Addressing

Domestic and Family Violence. Violence against Women, 30(14).

https://doi.org/10.1177/10778012231179212

Ross, D. A., Hinton, R.,

Melles-Brewer, M., Engel, D., Zeck, W., Fagan, L., Herat, J., Phaladi, G., Imbago-Jácome, D.,

Anyona, P., Sanchez, A., Damji, N., Terki, F.,

Baltag, V., Patton, G., Silverman, A., Fogstad, H.,

Banerjee, A., & Mohan, A. (2020). Adolescent Well-Being: A Definition and

Conceptual Framework. Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(4),

472–476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.06.042

Rothman, K. J., & Greenland, S.

(2018). Planning study size based on precision rather than power. Epidemiology, 29(5), 599–603.

https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0000000000000876

Sardinha, L. M., & Catalán, H. E. N.

(2018). Attitudes towards domestic violence

in 49 low- and middle-income countries: A gendered analysis of prevalence and

country-level correlates. PLOS ONE, 13(10), e0206101.

https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0206101

United Nations International

Children’s Emergency Fund. (2019). La

violencia en el hogar.

https://www.unicef.org/uruguay/la-violencia-en-el-hogar

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The

Ecology of Human Development. In The Ecology of Human Development (p.

7). Harvard University Press.

https://books.google.com/books/about/The_Ecology_of_Human_Development.html?id=OCmbzWka6xUC

Walker, L. (1979). The Battered

Woman. Scientific Research an Academic Publisher, 11(08),

330–336. https://doi.org/10.4236/CRCM.2022.118046

World Health Organization. (2024). Violence

against women.

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women