http://dx.doi.org/10.24016/2024.v10.381

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Affective Behavioral Disturbances: An Interbehavioral Analysis

Alteraciones

Afectivo-Conductuales: Un análisis interconductual

Claudio Carpio 1*,

Virginia Pacheco Chávez 1, Valeria Olvera Navas 1

1 Facultad de Estudios

Superiores Iztacala, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico city, Mexico.

* Correspondence: claudio.carpio@iztacala.unam.mx

Received: November 17, 2023 | Revised: March 19, 2024 |

Accepted: May 21, 2024 | Published Online: May 25, 2024

CITE IT AS:

Carpio,

C., Pacheco Chávez, V., & Olvera Navas, V. (2024). Affective Behavioral

Disturbances: An Interbehavioral Analysis. Interacciones,

10, e381. http://dx.doi.org/10.24016/2024.v10.381

ABSTRACT

Background: The progress of any science, such as

psychology, is achieved not only by accumulating empirical evidence but also by

refining the conceptual structures that give theoretical meaning to such

evidence. Objective: To analyze the concept of mental health and the

logical-conceptual structure that supports it, describing its limitations and

contradictions. Alternatively, based on the postulates of interbehavioral psychology,

the concept of affective behavioral changes is proposed, and a classification

of these changes is developed, based on the functional quality of the disturbed

behavior. Method: This research is a theoretical study. Conclusions: Dualistic

traditions in psychology have pathologized affective behavioral alterations as

if they were diseases (mental or brain). The interbehavioral postulation

outlined here is a conceptual alternative that can support theoretical and

methodological developments that improve the position and contribution of

psychology to theorizing and solving human problems in the field of health.

Keywords: Health, affective disturbances, behavior, analysis, psychology.

RESUMEN

Introducción: El progreso de

cualquier ciencia, como la Psicología, se logra no solo acumulando evidencia

empírica sino también refinando las estructuras conceptuales que dan significado

teórico a dicha evidencia. Objetivo: Analizar la noción de salud

mental y la estructura lógico-conceptual que la sustenta, describiendo sus

limitaciones y contradicciones. Alternativamente, a partir de los postulados de

la psicología interconductual, se propone el concepto de alteraciones afectivas

de la conducta y se desarrolla una clasificación de las mismas, basada en la

cualidad funcional de la conducta que se altera. Método: Esta investigación es un estudio teórico. Conclusiones: Las tradiciones dualistas en

psicología han patologizado las alteraciones afectivas del comportamiento como

si fueran enfermedades (mentales o cerebrales). La postulación interconductual

que aquí se esboza es una alternativa conceptual que puede apoyar desarrollos

teóricos y metodológicos que mejoren la posición y contribución de la

psicología a la teorización y solución de problemas humanos en el campo de la

salud.

Palabras claves: Salud, trastornos afectivos, comportamiento, análisis, psicología.

Most

psychologists likely accept as an unquestionable truth that psychology is responsible for

preserving mental health and treating its alterations. To doubt this could be

judged as utter folly or, in the extreme of disciplinary anger, as a

manifestation of insanity. However, since science progresses not only by

accumulating empirical evidence but also by refining the conceptual structures

that give theoretical meaning to such evidence (cf. Kantor, 1958, 1963, 1969;

Kuhn, 1962; Turbayne, 1962), this paper briefly examines some conceptual

assumptions on which an important part of the professional practice of

psychology in the clinical or health field has rested, especially those related

to the notion of mental health, the nature of the mental, and the idea of

altered affective states. Based on this examination, an interbehavioral point

of view is presented to support a different, objective, and naturalistic

approach, which can help improve the psychological contribution in the field of

health, with special emphasis on affective alterations of behavior.

MENTAL

HEALTH: DIMENSION OF A STATE OR FIELD OF PSYCHOLOGICAL ACTION?

The well-known experience of Clifford

Beers during his time in different psychiatric hospitals in the early twentieth

century (Beers, 1908/1980) was one of the first and most transcendent calls for

attention to the deplorable state of psychiatric treatment of the insane or

mentally ill and also represented the starting point for the social movement

of mental hygiene (Beers, 1980; Dain, 1980; Deutsch, 1937; Grob, 1994; Ridenour, 1961),

that the United States of America initially promoted the National Commission of Mental

Hygiene (created in 1909) and later the Committee of Mental Hygiene (founded

in 1919), whose work allowed to consolidate the World Federation of Mental Health (formalized

in 1948) as the most visible international organization

that claims and promotes more respectful treatment of the dignity and

human rights of persons held in psychiatric care facilities. A fact of interest

in this process is that the arguments used by these organizations to support

their claims were, and still are, ideological, political, and legal rather than

conceptual, technical, or scientific. In this regard, it is revealing the

indistinct use they usually make of the concepts of mental hygiene and mental health to refer

to their subject of interest in their basic documents and even in the

institutional name that identifies them.

At the end of the 1940s, the demands of pro-mental hygiene (or health)

organizations were strengthened thanks to the

interest of some governments to address the growing cases of mental problems

(e.g., severe anxiety, addictions, insomnia, suicide attempts, irritability,

anguish, panic attacks, etc.) in ex-combatants of the Second World War, which

had high economic, political, and social impact. This may explain why, since

its creation in April 1948, the World Health Organization (WHO) has included a

section on mental health that

would be dedicated exclusively to the attention of this problem (cf. Bertolote,

2008; Lopera, 2015), giving it such importance that it even appears as a

central element of its declaration of principles, which states that

“Health is a state of complete physical, mental [emphasis

added], and

social well-being, and not only the absence of disease or infirmity” (WHO,

2020, p. 1).

In this definition of health, it is

evident that the mental constitutes a constituent

aspect of health that must be treated with the same rigor as its

other aspects, the physical and the social; however, many notice in it the

explicit recognition of a special type of health, the mental. To tackle this

incorrect interpretation, Bertolote (2008) points out that:

“It

should be noted that mental, in the definition of health of the WHO (as well as

physical and social), refers to

dimensions of a state and not to a specific domain or discipline [emphasis added]. Consequently, according to this concept, it is incongruous

to speak of physical health, mental health, or social health. If we wanted to

specify a particular dimension, it would be more appropriate to use the term

well-being and not health (e.g., mental well-being or social well-being). This

negligent use of the word health seems to have begun when mental hygiene

(social movement or domain of activity) was replaced by mental health

(originally intended as a state and then transformed into a domain or field of

activity). (p. 114)

To this, it should be added that the

definition of health proposed by the WHO refers to it in the singular and with

a capital letter, which also prevents it from being interpreted as a “holistic”

additive result of mental health plus social health plus biological health.

Consequently, if it is incorrect to speak of mental health as a field of

phenomena in itself, then it is also incorrect to grant legitimacy to the

so-called professions and institutions of mental health as

if it delimited a professional field of action (psychological or psychiatric)

and not an aspect or dimension of that state called health. However, an

incorrect and self-serving interpretation of the WHO definition of health by

medical associations, mainly psychiatric, and some organizations for the

human rights of psychiatric patients insists that “mental” refers to a type,

and not an aspect, of health, to justify their (i.e., their labor market) as

ad-hoc specialists (cf. Szasz, 1976, 1978, 2019), sheltered

in the cartesian dualistic philosophical and psychological traditions that have

conferred on the mental the onto-epistemic status of private, internal, and

unobservable events (cf. Kantor, 1966; Tomasini, 1988, 1995, 1996, 2008, 2016; Ryle,

1949; Wittgenstein, 1953; Kantor, 1966; Tomasini, 1988, 1995, 1996, 2008,

2016).

The

dualistic characterization of the mental

Among the most important difficulties that

psychology faces in collaborating satisfactorily with other disciplines

(biological and social) in the solution, prevention, or attenuation of health

problems is the unquestioned adoption

of the status that the dualistic tradition has given to the mental as a

thing that can only be known through its behavioral “manifestations” or

“expressions” and through the verbal report of the people who “experience it

privately”. (e.g., Descartes, 1980; Locke, 1976; Wundt, 2019, etc.). This characterization rests on the Cartesian theory of

mind (cf. Descartes, 1980), called by Ryle (1949) the “myth of the ghost in the

machine” or “official theory of mind”, which postulates the existence of two

coexisting substances in the human being: an extensive substance that is

characterized by occupying a place in space (the body) and a non-extensive

substance (ergo not occupying a place in space) that inhabits it and is

characterized by thinking (the soul).

The psychological theories that have

assumed the core of the official theory of mind have omitted to consider even

the most obvious and serious contradictions and paradoxes in their formulation,

among them that: a) if it is affirmed that the soul does not occupy a place in

space then it is not possible to preach of it any location and, therefore

it cannot be said to be within the body or to be contained by it; b) since

it is not corporeal or occupies any place in space, neither can it be

postulated that the soul interacts from within with the body that supposedly contains it, that

is, it cannot be proposed that the soul is capable of moving it, activate,

animate or boost it; c) by not recognizing spatial extension to the soul, the

official theory of mind is unable to refer to its hypothetical operation (i.e.,

thinking or cognition) in the same terms and temporal-spatial coordinates that

are used to refer to the occurrence of all known natural events, and; d) Since

the claim that the soul is within the body is untenable, it logically follows

that the action of the body could express, manifest or reveal the action of the

soul, which in turn would cancel out any possibility of knowing or identifying

when and how the soul acts (i.e., thought, cognition, will, etc.).

Despite the above, based on the dualistic assumptions

and assuming a nominalist conception of language, according to which words are

names or labels that designate and identify the things of the world they refer

to (cf. Tomasini, 1988, 1995, 1996; Wittgenstein, 1953; ), dualistic psychological traditions assume that

expressions involving terms such as thinking, perceiving, attending,

remembering, imagining, reasoning, and others of this type are references,

denotations, or descriptions of different events that occur in temporal-spatial

coordinates different from those of the situations in which such terms are used

(cf. Ryle, 1949). Thus, for example, if a person were to tell another (whom he

hugs, kisses, and caresses while secreting certain hormones and presenting

various reactions of excitement) that he loves him and that he likes him, dualistic approaches would affirm that this

person is informing, describing, narrating, or offering testimony of the events

that occur within him (i.e., the passionate acts of love). With such

statements, a single episode is conceptually divided into two: one of a public

nature (i.e., hugs, kisses, caresses, excitement, etc.) and another of a

private nature (i.e., passions and feelings) that are connected descriptively

by the terms “mentalistic” used (i.e., the sentimental or emotional

verbalizations emitted during the love episode). Some studies that illustrate

this theoretical perspective are, for example, the works of Barrett, Quigley,

Bliss-Moreau & Aronson (2004), De-Damas-González & Gomariz (2020),

Lolas (1987), Kyrylenko & Bobrovytska (2017), Scherer (2000).

Dualism and mental

health

The dualistic reasoning of the previous

example is not only found in cases of reference to hypothetical affective or

cognitive processes but also when terms are used that supposedly refer to

states or processes associated with the so-called mental health of people and their alterations, such as

anxiety, depression, anguish, etc. (Cfr. Ezama, Alonso & Fontanil, 2010) To

illustrate, imagine that a woman consults a doctor, psychologist, or

psychiatrist about possible solutions to the discomfort (e.g., tremors, dry

mouth, incontinence, stuttering, dizziness, etc.) that she suffers when night

comes and anticipates that her husband will arrive drunk and violently assault

her, as he usually does. In this hypothetical consultation, it would be very

likely that the woman reported fear, anguish, or anxiety as a cause of

insomnia, loss of appetite, physical discomfort, etc. The dualistic reasoning

in this example would again involve transforming a single episode (i.e., the

woman's exposure in the consultation) into two distinct episodes: one public

and observable (i.e., the woman's verbalizations of how she feels) and an

internal, private, and unobservable one (i.e., anxiety, anguish, fear, and

“described” thoughts). In this reasoning, a causal relationship is again postulated

between events, processes, or mental events (in this case the fear, anguish,

and anxiety supposedly referred to) and the physical alterations that “express”

or “manifest” them publicly (in this case tremors, dryness, stuttering,

incontinence, etc.). The causal connection thus proposed between “the

behavioral” and “the mental” constitutes the core of the dualistic

conceptualization of mental illness as a physical expression of internal

alterations not directly observable (Cfr. Bertolín-Guillén, 2023; Lemos,

Restrepo & Richard, 2008; Ramos-García, Gutiérrez-Yáñez,

Escamilla-Gutiérrez & Ortega-Andrade, 2023; Szasz, 1976, 2019).

Those who have assumed the dualistic

assumption that the mental is not publicly observable have attempted to solve

the problem of privileged access to its structural and operational

characteristics by constructing instruments that hypothetically assess verbal

reactivity to standardized “items” (whether in the form of “tests,”

“instruments,” “batteries,” “scales,” and other variants of planned

conversational interaction) by interpreting it as a reliably revealing

manifestation or expression. of the events, states, or processes that occur in

a private and unobservable way inside the person who responds to them.

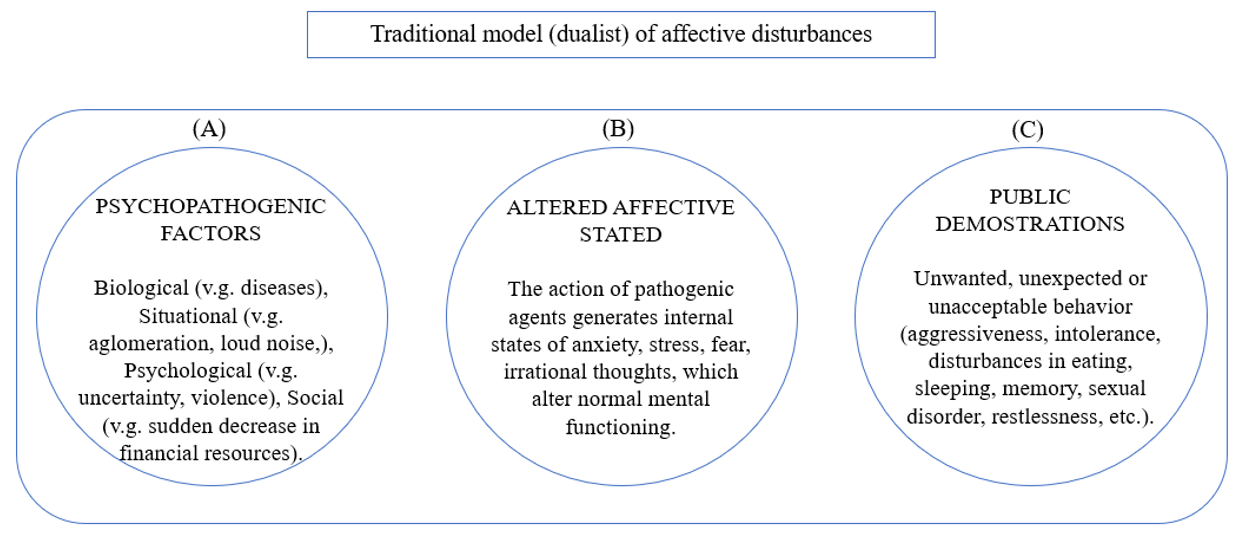

With some procedural or instrumental

variants, this strategy is overwhelmingly dominant in contemporary

psychological research, whose tools have ended up turning behavior into a

simple indicator or epiphenomenon of the mental, as represented in Figure 1 that

shows the dualistic conceptual architecture described and the postulated causal

relationships between: a) the existence of psychopathogenic factors in the

physical environment, social or psychological with the potential to cause

disturbances in “normal” or “healthy” mental state or functioning; b) the

alteration of internal affective processes (mentally or cerebrally controlled,

depending on the specific theoretical model adopted), and; c) the external

public expression or manifestation of internal disturbances, in the form of

unwanted, unexpected or unacceptable behavior.

Figure 1. Traditional model of affective disturbances

THE

INTERBEHAVIORAL POINT OF VIEW: A NATURALISTIC OPTION

Unlike the dualistic conception,

interbehavioral psychology (Kantor, 1924, 1926, 1933, 1956; Kantor & Smith, 1975) opposes

the idea that episodes involving mental, affective, or cognitive terms and

expressions (e.g., fear, think, reason, imagine, love, miss, crave, worry,

distress, etc.) involve the existence of internalized extra-episodic events or

events. Instead, it proposes to eradicate the dualistic dichotomies around the

hypothetical mind-behavior relations and to assume as a matter of psychological

study the interaction or

adjustment between the total action of complete organisms and the corresponding

activity of specific segments of their environment, assuming that in this

adjustment are basic factors both the biological equipment of the organism and

the physical characteristics of the objects of the environment. whose

functional properties evolve in the specific interactive history between them.

The proposition that it is the activity of

the whole organism that interacts with the activity of the

objects and events of the environment eliminates for psychology the need to

describe independently, partially, and separately the operation of each of the

multiple biological subsystems involved in each interactive segment. Also,

and above all, it avoids the temptation to locate in any of these biological

sub-systems specific psychological functions (a frequent

temptation in neuropsychological models

and theories), without limiting or questioning the legitimacy of analyzing the

particular operation of cells, tissues, or organs under particular stimulating

conditions at non-psychological descriptive levels, as occurs in the research

of nephrologists. Neurologists, pulmonologists, gastroenterologists,

pathologists, endocrinologists, etc.

This allows the interbehavioral

postulation to emphasize that the psychologist does not have this task of

physiological description but that of conceptualizing and describing the simultaneous operation of all the biological subsystems

organized during the interaction, not as a molecular physiological and summary

description of the entire biological operation but molarly as integrated action

in functional adjustments to the objects and events of the environment. For

this purpose, Kantor (1933; Kantor & Smith, 1975) developed the concept of reactive system to refer to

the configuration or organization of all biological reaction systems (endocrine, neurological,

motor, skeletal, visuomotor, gustatory, olfactory, thermomechanical, etc.)

during the organism's adjustment to the conditions of the environment with its

objects and events.

From this point of view, in all

interactions, the entire biological team of the organism is involved,

although its functional configuration is varied and unique in each of them,

with differentiated preeminences in each case. As an example, consider that

when dancing a Son Montuno in Old Havana (case 1), it is especially important

to enjoy and exercise, have a good hearing capacity, a reasonable kinesthetic,

and acceptable motor coordination. Of course, this does not mean that dancing

suspends other activities of the body, such as gastrointestinal activity or

kidney functions (in fact, a sudden variation in these or some other would

most likely drastically modify the dance). In another example, when cutting

wood for the home (case 2), although all biological systems also operate, the

most relevant are others, such as vision and the musculoskeletal system. It is

clear that the participation of each biological system is not equally critical

in both examples, but this does not mean that any operation is suspended while

the others act, so interbehavioral psychologists would affirm that it is

the person who dances and not the feet or ears, and that it is the people. those that cut the wood and

not the hands or arms; that is, it is the whole organism and not some of its

isolated parts that interact psychologically.

A relevant fact that should be emphasized

is that reactive systems are configured through historical processes of

integration or learning of skills and competencies that take place throughout

the interactive life of each person. Therefore, it can be said that

psychological behavior and its development are necessarily individual,

singular, unique, and unrepeatable, and their description cannot be limited to

the invariant relationships described by the chemical-biological sciences

(Carpio et al., 2007).

On the previous definitional basis,

interbehavioral psychology proposes that, although the biological team is the

substrate of the reactive systems, the description of these is not equal to or

reduced to that because the first develops as a result of the phylogenetic

evolution of the species while the others are configured based on the

ontogenetic vicissitudes of the individual. In this way, psychological action

itself is conceptualized as the functional result of the joint and organized

operation of all the biological components of the organism, integrated into

multiple systems or varied and changing reactive configurations, not static. In

fact, the processes of integration of the reactive systems through which the

psychological interaction capacities of organisms are shaped (i.e., skills and

competences) correspond to what has traditionally received the generic

name of Learning and development

processes (Carpio

et al., 2014). This postulation has, at least, two important consequences for

the study of psychological behavior: One, that the description and

characterization of behavior, as a relationship and adjustment

between actions of the whole organism

and the actions of the objects and events of the environment with which it

interacts, cannot be reduced to a topographic or morphological inventory of the

actions of the organism; Two, that the relationship cannot be given spatial location

because relationships do not occupy a place in space (although the objects and

events that are related to occupy it) and therefore one cannot speak of

“internal” or “external” behavior, and therefore it is incorrect to propose

that an “external” form of behavior (e.g., verbally answering a questionnaire)

is an indicator of another “internal” form of behavior (e.g., cognitive

processes, affective states, etc.) or that this is the cause of it.

Based on the interbehavioral

postulation, it is not rejected or denied that people think, reason, imagine,

love, sadden, or distress, but the dualistic assumptions of psychological

theories that have conferred on these expressions the status of reference and

evidence of trans or extra-episodic, internal, private, and unobservable events

are questioned. On the contrary, interbehavioral psychology conceptualizes them

as part or integral components of interactive adjustment, along with all other

actions that are executed during interactions, colloquially called “cognitive”,

“emotional” or “mental”. For this reason, it also proposes to elaborate

objective and naturalistic descriptions to give them a more coherent treatment

in the conceptual sense and a more congruent methodological approach that

allows for better integration with other disciplines in the construction of

solutions to the multiple problems in the field of health (cf. Kantor, 1933;

Kantor & Smith, 1975).

A

GENERAL OBJECTIVE ORIENTATION TO SO-CALLED MENTAL HEALTH

That our heartbeat is not, in any way, an

alarm signal. However, if the heart palpitations are so intense and accelerated

that they cause us to suspend our regular activities in a certain situation,

this will likely have undesirable or unpleasant effects. Similarly, if at any

time sudden changes occur in our sensory-motor abilities (such as when we

“stop feeling” a part of our body or feel that we “cannot move it”; when

we “cannot see” or our “tongue locks”, etc.), the usual course of the activities

and tasks we were performing at that moment will most likely be altered,

subtracting effectiveness, appropriateness, congruence, or behavioral

coherence. Cases like these and others similar (such as insomnia, lack of

concentration, some sexual dysfunctions, aggressiveness, intolerance to

ambiguity, eating disorders, addictions, nightmares, etc.) are usually called

diseases, alterations, disorders, pathologies, or “mental” problems, and it is

common to postulate as their causes anguish or anxiety in most dualistic psychological

approaches, which use these terms practically interchangeably to postulate

various types of states or responsible internal entities, inevitably incurring

the logical problems of dualism (v.gr. Arita, 2001; Silva, 2007; Simon, 2009).

In contrast to dualistic psychology,

behavioral orientation, in general, has sought a much more objective

naturalistic approach without appealing to internal mental entities or

processes. For example, formulations based on the theory of conditioning (cf.

Pavlov, 1927; Skinner, 1931, 1935, 1938) have conceptualized anxiety as the

alteration, or disruption, of current behavior by the presence of a conditional

stimulus that generates affective responses (i.e., those that by themselves do

not produce effects on the stimulating conditions of the environment) that are

intense, incompatible, or competitive with the altered behavior. This

formulation is illustrated by Watson's famous work with the child Albert

(Watson &

Rayner, 1920), which showed how the “ear or anxiety responses” (e.g., crying,

startling, distancing, etc.) that the child presented to a white rat that

previously did not provoke them developed from being repeatedly made to

coincide with a sudden and strong noise produced by the tapping of a metal plate.

Additionally, Watson and Rayner (1920) observed that these conditioned fear

responses were also presented to a dog, a coat, or pieces of wool, that is,

generalized towards objects similar to the white rat.

Similarly, Estes and Skinner (1941)

defined anxiety as “the response to some present stimulus that, in the

past, has been followed by a disturbing

stimulus [...] This disturbing stimulus does not precede or

accompany the emotional state but is anticipated in the future” (p. 573),

and to evaluate its quantitative properties, they used 24 albino rats of six

months, which they subjected to a program of fixed interval (FI) of four

minutes, reinforcing the leverage response. After two weeks under FI, they introduced during

the session a tone that lasted three minutes, followed by an electric shock,

repeating this arrangement several times during some sessions. Subsequently,

the tone duration was increased to five minutes, and the tone-shock arrangement

was presented only once during the sessions, although the tone alone, without

the shock, was presented several more times. The results showed that the

response rate decreased markedly in the presence of tone. This suppression of

the response, or “freezing,” during the tone was precisely the disturbing

effect of the conditioned aversive stimulus, that is, anxiety as a conditioned

suppression of the response maintained independently by positive reinforcement.

A consequence of the work of Estes and

Skinner (1941) was the consolidation of the area of experimental research on

conditioned suppression, with the study of Hunt and Brady (1951) being one of

the most recognized in the field. In that study, the authors worked with

water-deprived rats subjected to a variable interval (VI) reinforcement

program, also reinforcing the leverage response. Subsequently, with a classical

forward conditioning procedure, they presented a sound for five minutes,

followed by an electric shock.

Of such an arrangement, they observed an

almost total decrease in the lever response in the presence of tone, as well as

gasps, tremors, and defecation in rats. These effects of suppression of the

operant response and the appearance of conditioned emotional responses have

been repeatedly confirmed by other authors (e.g., Arcediano et al., 1996; Di Giusto & Bond, 1978;

James et al., 2013; Kelleher et al., 1963; Riddle, & Cook, 1963; Sidman, 1958).

In addition to the suppression of operant

responses and the emergence of conditioned emotional responses such as those

described, other studies have shown the development of organic lesions as part

of a “behavioral anxiety syndrome” (e.g., muscle pain, headaches, ulcers,

etc.). An example of these studies is that of Sawry and Weisz (1956), who

placed a group of rats in a box, which at one end contained water and at the

other end contained food; both containers were electrically charged. In the

case of remaining in the center of the box, the animals did not access the

water or food; on the contrary, only if they approached any of the containers did,

they receive an electric shock (for some in the water and others in the food).

In one more group, rats received food and water in the containers without

receiving electric shocks. The results showed that six of the nine rats in the

first group developed gastric ulcers, while none of the subjects in the other

groups did. The design of the study allows us to consider with a reasonable

margin of certainty that the ulcers were not caused by the electric shocks but

by the presence of the stimuli (i.e., the containers) associated with

them.

Another work with results compatible with

the previous ones is the well-known study of the "executive monkeys"

in which Brady (1958) worked with pairs of monkeys, one of which (the

“executive monkey”) could operate a lever and thereby postpone the occurrence

of an electric shock in the feet of both monkeys. Every 20 seconds, a light was

presented, indicating the occurrence of the next electric shock and also

signaling the opportunity to emit the avoidance response. Each day, pairs of

monkeys spent six hours in the chamber for six hours of rest. In all cases, the

executive monkeys developed gastric ulcers, in some cases so severe that some

of them died from them, while the passive monkeys did not develop any lesions

at all. Based on these results, Brady (1958) concluded that the anticipatory

responses to the experimental situation that occurred during the rest period

were those that favored the development of ulcers.

Obviously, a notable advantage of the

works described above is that none of them postulate internal, private, and

unobservable mental entities or processes (e.g., anxiety, anguish) as

responsible for the observed behavior and its pathological effects on the

organism, but all focus their explanation on the relationship between stimuli

(public, observable, measurable, and manipulable) that makes one of them a sign

of a subsequent aversive event, evoking incompatible responses (e.g.,

“freezing”) with the suppressed response or harmful to the organism (e.g.,

excessive secretion of gastric acids, increases in blood pressure, increases in

heart rate, etc.).

Despite the conceptual improvement

represented by the Skinnerian tradition, Kantor (1933; Kantor & Smith, 1975)

considered it necessary to go beyond the theories of conditioning and proposed

to distinguish affective reactive systems (in which the action of the organism

has no effect on the objects and events of the environment with which it

interacts) from effective reactive systems (those in which the action of

the organism does produce direct effects on the objects and events of the

environment with which it interacts) and, based on this, to differentiate

emotional interactions from

sentimental interactions.

According to Kantor (1933; Kantor & Smith, 1975), in

emotional interactions, the presence of a certain stimulus activates the

operation of the reactive system always in the same way in all intact

organisms of the same species, so that the behavioral result of its interaction

with effective reactive systems is the

functional disorganization of these, regardless of the interactive history

of organisms, so they are biological and not psychological. An illustrative

example of these interactions is in cases in which the presence of an intense,

sudden, and surprising stimulus functionally disorganizes the effective action

that is taking place, as occurs when the sudden and intense sound of a horn

while driving a car alters the precision of driving to such an extent that

control of the vehicle can even be lost. These interactions also occur when,

for example, the pain produced by the bite of an animal surprises us while we

read, and we immediately suspend the reading by orienting our eyes to the area

of the picket. In this case, the effectiveness of the reading behavior is

momentarily lost by the operation of the affective-reactive system (sensory, in

this example) activated by the picket. A further example of the emotional

interactions thus characterized is when there is a sudden loss of lift (as in

the excessively rapid descent of an elevator, during an episode of turbulence

in a flight, or in an intense earthquake) and immediately the interaction that

is taking place is disorganized, affecting for a moment the operation of the

effective reactive systems. In all these cases, the operation of the

affective-reactive systems occurs in the same way in all people, regardless of

the experience or history they have with the stimuli involved, and always as a

momentary disturbance or disorganization of effective behavior. This is why

Kantor (1933; Kantor & Smith, 1975)

stresses the non-psychological nature of emotional interactions.

Unlike the above, Kantor (1933) argues that in

sentimental interactions, the operation of affective reactive systems obeys the

history of previous interactions that individuals have had with objects and

events in particular situations, so this does not occur in the same way in all

individuals. To illustrate, consider the case of a car driver who begins

to cry, tremble, and moan when crossing a bridge whose railings are painted

green, in such a way that he even loses control of the vehicle. This, of

course, does not happen to all the people who cross said bridge, because

neither the bridge nor the railings or their green color by themselves produce

these reactions, but these occur only because that driver has a particular

history with them in certain situations (it could be that on that bridge or in

a very similar one, the driver suffered a strong love disappointment). In this

case, the intense activity of the affective reactive systems is due to the

fragmentary elements of that situation (the bridge and its green railings), and

it is precisely because of the intensity of the affective activity that the

effectiveness of the behavior in that situation is altered. Insisting, it must

be said that this happens because of the peculiar interactive story of the driver,

different from that of the rest of the other people, in which neither the

bridge nor its green railings will produce the disruptive affective activities

described. What should be insisted on is that this experiential ontogenetic

characteristic is what confers the psychological character to the affective

alteration of behavior that Kantor (1933; Kantor & Smith, 1975) calls sentimental interactions.

From the Kantorian interbehavioral point

of view, it is assumed that affective reactive systems involving glandular,

sensory, autonomic neuronal activity, smooth muscle activity, etc. participate

outstandingly, and it is emphasized that this does not suppress in any

way the operation of effective reactive systems involving the activity of

striated muscles, skeletal action, central neural activity, etc., but is

integrated into the setting. From this, it follows that these are constituted

and are always present as

components, aspects, or dimensions of all psychological interactions. In this

way, it can be said that affectivity and effectiveness are adjectives that

qualify or characterize reactive systems but not total behavior as interaction,

so it is not correct to speak of emotions or feelings in isolation, nor of

emotional or sentimental behavior, but of the affective and effective dimensions of

psychological behavior, whose balance can be altered at a specific time, in

particular situations, by the predominance of one over the other in such a way

that one or more of the functional

qualities of behavior is altered.

FUNCTIONAL

QUALITIES OF BEHAVIOR

According to Carpio (1994), the functional

qualities of behavior can be identified based on the adjustment criteria that

individuals must satisfy in each of their interactions. Such criteria

constitute the performance requirement indispensable for the functional

adequacy of the individual's actions to the characteristics of the objects and

events of the medium in each interactive episode and may derive from the

morphological characteristics of the situation but may also be imposed by other

individuals (in the form of orders, requests, instructions, suggestions, etc.)

and even by the individual himself (as a self-instruction, objective, or

goal).

In the simplest case, the criteria of

ajustivity establish the requirement that the activity of the individual is adapted morphologically

in time and space to the morphology and temporo-spatial structure (duration,

intervals, density, place of occurrence, etc.) of unique stimuli (as in

temporal conditioning procedures) or paired with others (as in simultaneous or

delayed conditioning procedures, forward or backward). In these cases,

behavioral functionality occurs as a temporo-spatial adjustment of the individual's

activity that, in some cases, seeks contact with some stimulating events (as in

appetitive conditioning) or distancing from others (as in aversive

conditioning). In this case, the functional quality of the behavior is

precisely the ability to adapt, or ajustivity, to the morphology and temporal

structure of the stimulating environment.

The second type of adjustment criteria

defines effectiveness as the characteristic functional quality of behavior. In

the words of Carpio (1994):

“Effectiveness refers to the

temporal, spatial, topographical, durational, and intensive adequacy of the

response to regulate the occurrence and temporo-spatial and intensive

parameters of stimulus events...Operant conditioning and its procedures,

phenomena studied as practical intelligence and others, are examples of this

level in which the effectiveness of the responses is the central characteristic

of the interaction [emphasis added]” (p. 64).

One type of functionality, more complex

than effectiveness, derives from the criteria of appropriateness. This

functionality was originally characterized as:

the

effective variability of the response and its properties according to the variability of the environment and

its conditions. The answer, to put it another way, must be situationally

relevant to operational contingencies and their continuous variation...Sample

matching procedures, studies on concept formation in animals, and rule

learning, among others, illustrate the level at which the central

characteristic of interaction is appropriateness [emphasis added] (Carpio,

1994, p. 65).

To characterize the functionality of

behavior that derives from fit criteria linked to the functional correspondence

between interactive segments say-do and say-tell, Carpio (1994) proposed that:

congruence describes a characteristic that is

only present in interactions in which reactivity is morphologically independent

of the physicochemical properties and the spatio-temporal parameters of the

situation, that is, when functional contingencies are established by linguistic

substitution. Congruence in these interactions refers to the correspondence

between linguistically substituted contingencies and actual situational

contingencies. Finally [emphasis added], at the most complex level, in which the organization of

contingencies occurs as contingencies between substitutions as a linguistic

product, that is, that the

individual with his behavior establishes new relationships between linguistic

products abstracted from the concrete situations in which they are elaborated,

coherence, as an organization of the correspondences described at the previous level,

is established as the functional characteristic that describes the

correspondence between sayings as a way of doing[emphasis added]. (pp. 65-66).

In short, the functional qualities of

behavior constitute the updating of the interactive capacities of individuals

who depend both on their biological equipment and on the skills and

competencies they learn and develop throughout their individual interactive

history, and whose functional appropriateness is differentially

“selected” moment by moment by the criterion of adjustment to be satisfied and

by the morphological and functional characteristics of the situations in which

every interaction occurs. Table 1 synthesizes the functional qualities of

behavior as interactive capabilities.

Table 1. Functional qualities of psychological

behavior

|

Functional qualities of behavior |

Definition |

|

Ajustivity |

Capacity to adjust the spatio-temporal,

morphological and intensive distribution of the activity with the spatio-temporal parameters of the stimulating conditions,

unalterable by the individual. |

|

Effectiveness |

Capacity to produce effects on the

distribution and spatio-temporal parameters of

stimulating conditions, regulating their values (including their occurrence

or omission). |

|

Appropriateness |

Capacity to adapt the spatio-temporal,

morphological and intensive distribution of the activity to the local

functional variations of the stimulating conditions. |

|

Congruence |

Capacity to deploy activities

conventionally corresponding to linguistic conditions of stimulation. |

|

Coherence |

Capacity to establish and apply functional

correspondence criteria between different segments or linguistic products. |

AFFECTIVE

ALTERATIONS OF BEHAVIOR

The concept of affective alteration of

behavior that we propose here refers to the condition in which the exacerbated

operation of the affective reactive systems modifies the functional quality of

the distinctive behavior in an interaction or set of functionally linked

interactions at a given time (Cfr. Alonso-Vega, Núñez, Lee & Froján, 2019;

Kantor & Smith, 1975; Piña, 2008). This characterization assumes that the

affective operation is triggered by the presence, physically or verbally

enunciated by the individual himself or by others, of stimulating elements that

arouse it due to a particular learning history (as in the aforementioned

example of the green railings of the bridge that shock a person who passes by).

Equally, it assumes that the alteration may imply the deterioration of the

corresponding functional quality but also its improvement. These variants

illustrate the freezing that a person can suffer before the sudden appearance

of an aggressive animal (e.g., a dog that barks and throws itself fiercely) or

the rapid escape to a safe place (e.g., a high and inaccessible place for the

animal) without having previously exercised that climbing capacity. In another

example, it is common to observe the “nervousness” of some people in exam

situations, in which they forget even the most elementary of what the exam

explores, while in others their intelligence and memory are “sharpened,”

which makes them overcome the exam in question more successfully.

Terms such as

“phobia”, “depression”, “anxiety”, “stress”, “burnout”, and

“affective alterations of personality”, among others, constitute labels that

are placed on behavioral observations that correspond to what we conceptualize

here as affective alterations of behavior. The difference is not only

nominative, but also much deeper, it is conceptual: the postulation of internal

entities (mental or cerebral) as causal agents of behavior is rejected; departs

from medical conceptions that pathologize behavior (Cfr. Szasz, 1961,1976);

abandons the dichotomy between affectivity and behavior by recognizing that in

all the interactions of individuals there is always an affective and an

effective dimension; it transcends the reflexological tradition that only

recognizes one functional level of behavior (the conditional reflex) by

postulating five levels of interactive functionality; eradicates the notion

that any affective alteration implies a deterioration of interactive

functionality by warning that in some cases these can improve it; it becomes independent of dualistic conceptions by locating

the origin and singularity of affective alterations of behavior in the

interactive history of each individual, linking it with the learning processes

that occur in it.

Based on the above, it is possible to

envisage a tentative functional classification of affective alterations of

behavior, different from those derived from dualistic theories. An advantage of

attempting a functional classification is that it can guide research and

intervention according to the level and type of interactive functionality that

is altered. For this purpose, it is possible to propose five functional

variants of affective behavioral alterations:

1.

Affective alterations of interactive

ajustivity;

2.

Affective alterations of interactive

effectiveness;

3.

Affective alterations of

interactive appropriateness;

4.

Affective alterations of interactive

congruence;

5.

Affective alterations of interactive

coherence.

For the identification of each of these

variants, the functional quality of the behavior that is altered (negatively or

positively) by an exacerbated operation of the affective reactive systems,

which is due to the presence of stimulant components that form or have been

part of other interactions of individuals, is privileged. Thus, the presence

of, for example, a stimulus that has previously been related to an aversive

event can alter the behavior of the individual, but depending on the altered

functional quality, we could be facing one or another type of affective

alteration. At this point, the functional quality of the altered.

BY WAY

OF PRELIMINARY CONCLUSION

The dualistic traditions in psychology

have produced theoretical models that, regardless of the most flagrant logical

inconsistencies, have pathologized affective alterations of behavior as if they

were diseases (mental or cerebral) that the psychologist, physician, or

psychiatrist must prevent, cure, or alleviate through action strategies that,

they suppose, are essentially therapeutic. For this reason, they have developed

methods of research and intervention that privilege the verbal report of

people, to which they grant the character of “revealing”, “informative”, or

“descriptive” of their mental interiority to which only each one has access due

to the private and publicly inaccessible character that is granted to the

mental or psychic.

The critical examination of the

logical-conceptual structure of the dominant mentalist traditions in the field

of so-called mental health leads to the search for more coherent, objective,

and naturalistic theoretical alternatives that enhance psychological research

and intervention on more solid foundations. The interbehavioral postulation

outlined here is, in our opinion, a conceptual alternative that can support

theoretical and methodological developments that improve the position and

contribution of psychology to the theorization and solution of human problems

in the field of health.

Behavior (and the type of alteration)

warns against the theoretical temptation to characterize it morphologically and

to try generic-universal explanations that avoid the singularity of the

processes of the historical constitution of individual behavior.

ORCID

Claudio

Carpio: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9183-8690

Virginia

Pacheco Chávez: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9316-1070

Valeria

Olvera Navas: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9915-5728

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

Claudio Carpio: Conceptualization,

Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing and Visualization.

Virginia Pacheco

Chávez: Conceptualization, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review &

Editing and Visualization.

Valeria Olvera Navas: Conceptualization,

Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing and Visualization.

FUNDING

SOURCE

This work was

supported by PAPIME-DGAPA-UNAM, grant to PE301223 project.

CONFLICT OF

INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Acknowledgments to Mairene García Plata, Rodrigo Vidal Carrera and René

Rincón Reyes.

REVIEW

PROCESS

This study has been reviewed by external peers in double-blind mode.

The editor in charge was David Villarreal-Zegarra. The review process is included as supplementary material 1.

DATA

AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Not applicable.

DECLARATION

OF THE USE OF GENERATIVE ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

The authors declare that they have not made use of artificial

intelligence-generated tools for the creation of the manuscript, nor

technological assistants for the writing.

DISCLAIMER

The authors are responsible for all statements made in this article.

REFERENCES

Alonso-Vega, J.,

Núñez, M., Lee, G. & Froján, M.X. (2919). El tratamieto de enfermedades

mentales graves desde la investigación de procesos. Conductual, 7(1), 44-65.

https://doi.org/10.59792/YVVN1823

American Psychiatric

Association. (2023). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders

(5th ed.). APA.

Arcediano, F.,

Ortega, N. & Matute, H. (1996). A behavioural preparation for the study of

human Pavlovian conditioning. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology,

49(3), 270-283. https://doi.org/10.1080/713932633

Arita, W. B.Y.

(2002). Ansiedad

y síntomas de estrés en estudiantes universitarios. Enseñanza e

investigación en psicología, 6(2), 297-302. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A115973212/IFME?u=anon~38df10cb&sid=googleScholar&xid=d062c40a

Barrett, L.F.,

Quigley, K.S., Bliss-Moreau, E. & Aronson, K.R. (2004). Interoceptive

sensitivity and self-reports of emotional experience. Journal of personality

and social psychology, 87(5), 684-697.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.87.5.684

Beers, C. (1980). A

Mind That Found Itself: An Autobiography; University of Pittsburgh Press;

Pittsburgh. (Original work published 1908).

Bertolín-Guillén,

J.M. (2023). Psicopatlogía y el problema epistémico de la filosofía de la

mente. Norte de salud mental, 19(69),

47-55. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=9372271

Bertolote, J.

(2008). The roots of the concept of mental health. World Psychiatry,

7(2), 65-128. https://doi.org/10.1002%2Fj.2051-5545.2008.tb00172.x

Brady, J. (1958).

Ulcers in "executive" monkeys. Scientific American, 199(3),

95–104. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24944795

Carpio, C. (1994).

Comportamiento animal y teoría de la conducta. En: L. Hayes, E. Ribes y F.

López (Eds.). Psicología Interconductual. EDUG.

Carpio, C., Canales,

C., Morales, G., Arroyo, R. & Silva, H. (2007). Inteligencia, creatividad y

desarrollo psicológico. Acta Colombiana de Psicología, 10(2),

41-50.

http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?pid=s0123-91552007000200005&script=sci_arttext

Carpio, C. Pacheco,

V., Canales, C., Morales, G. & Rodríguez, R. (2014). Comportamiento

inteligente y creativo: efectos de distintos tipos de instrucciones. Suma Psicológica, 21(1),

36-44. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0121-4381(14)70005-0

Dain, N. (1980). Clifford

W. Beers: Advocate for the Insane; University of Pittsburgh Press.

De-Damas-González,

M. & Gomariz, M.A. (2020). La verbalización de las emociones en educación

infantil. Evaluación de un programa de conciencia emocional. Estudios sobre

educación, 38, 279-302. https://doi.org/10.15581/004.38.279-302

Descartes, R.

(1980). Discurso del método, Meditaciones metafísicas, Reglas para la

dirección del espíritu, principios de la Filosofía. Porrúa.

Deutsch, A. (1937). The

Mentally Ill in America: A History of Their Care and Treatment from Colonial

times. Doubleday, Doran and Company

Inc. https://doi.org/10.7312/deut93794

Di Giusto, E. &

Bond, N. (1978). One-trial conditioned suppression: effects of instructions on

extinction. American Journal of Psychology, 91(2),

313-319. https://doi.org/10.2307/1421541

Estes, W. &

Skinner, B. (1941). Some quantitative properties of anxiety. Journal of

Experimental Psychology, 29(5), 390–400.

https://doi.org/10.1037/h0062283

Ezama, C.E. Alonso,

Y. & Fontanil, G.Y. (2010). Pacientes, síntomas, trastornos, organicidad y

psicopatología. International journal of psychological therapy, 10(2), 293-314.

https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=3229782

Grob, G. (1994). The

Mad Among Us: A History of the Care of America’s Mentally Ill; The Free

Press.

Hunt, H. &

Brady, J. (1951). Some effects of electro-convulsive shock on a conditioned

emotional response ("anxiety"). Journal of Comparative and

Physiological Psychology, 44(1), 88-98.

https://doi.org/10.1037/h0059967

James, W., Newton,

P., Roche, B. & Dymond, S. (2013). Conditioned suppression in a virtual

environment. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(3),

552-558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.11.016

Kantor, J. (1924). Principles

of Psychology. Ohio: Principia Press.

Kantor, J. (1933). A

survey of the science of psychology. Ohio: Principia Press.

Kantor, J. (1956).

W. L. Bryan, Scientist, Philosopher, Educator. Science, 123(3189),

214. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.123.3189.214

Kantor, J. (1958). Interbehavioral

psychology: A sample of scientific system construction. Principia Press.

https://doi.org/10.1037/13165-000

Kantor J. (1963). The

Scientific Evolution of Psychology. Ohio: Principia Press.

https://doi.org/10.1037/11183-000

Kantor, J. (1966).

Behaviorism: Whose image? The Psychological Record, 13,

499-512. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03393552

Kantor, J. (1969).

Scientific psychology and specious philosophy. The Psychological Record,

19(1), 15–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03393823

Kantor, J. &

Smith, N. (1975). The Science of Psychology: An Interbehavioral Survey. The

Principia Press.

Kelleher, R., Gill,

C., Riddle, W. & Cook, L. (1963). On the use of the squirrel monkey in

behavioral and pharmacological experiments. Journal of the Experimental

Analysis of Behavior, 6(2), 249–252.

https://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.1963.6-249

Kuhn, T. (1962). The

Structure of Scientific Revolutions. University of Chicago Press.

Kyrylenko, T.S.

& Bobrovytska, A.A. (2017). Peculiarities of verbal description of personal

emotions by representatives of different ethnocultural communities. Ukranian

psychological journal, 3 (5), 101-112.

Lemos, . M., Restrepo, O.D. & Richard, L.C. (2008). Revisión crítica del

concepto “psicosomático” a la luz del dualismo mente-cuerpo. Pensamiento

psicológico, 4(10), 137-147.

https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=2792749

Locke, E. (1976). Ensayo

sobre el entendimiento humano. Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Lolas, F. (1987). Verbal Behavior,

emotion, and psychosomatic pathology. In Lolas, F., Mayer, H. (Eds-)

Perspectives on stress-related topics. Springer-Verlang Berlin,

Heildelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-69057-0_10

Lopera, J. (2015).

El concepto de salud mental en algunos instrumentos de políticas públicas de la

Organización Mundial de la Salud. Revista Facultad Nacional de Salud Pública,

32(1), 11-20. https://doi.org/10.17533/udea.rfnsp.19792

Organización Mundial

de la Salud [OMS]. (2020). Documentos básicos (49ª ed.).

OMS. https://apps.who.int/gb/bd/pdf_files/BD_49th-sp.pdf

Pavlov, I. (1927). Conditioned

reflexes: an investigation of the physiological activity of the cerebral

cortex. Oxford University Press. 10.5214/ans.0972-7531.1017309

Piña, J. (2008).

Variaciones dobre el modelo psicológico de salud biológica de Ribes:

justificación y desarrollo. Universitas psychologica, 7(1), 19-32.

Ramos-García, J.,

Gutiérrez-Yáñez, M. &Ortega-Andrade, N. (2023). Mente y salud mental en

psicología: un análisis conceptual desde la perspectiva conductual. Educación

y salud. Boletin científico instituto de ciencias de la salud universidad

Autónoma del estado de Hidalgo, 11(22), 105-111. https://doi.org/10.29057/icsa.v11i22.10097

Ridenour, N. (1961).

Mental Health in the United States A Fifty-Year

History. Harvard University Press.

https://doi.org/10.4159/harvard.9780674420267

Ryle, G. (1949). The

concept of mind. Hutchinson https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203875858

Sawrey, W. &

Weisz, J. (1956). An experimental method of producing gastric ulcers. Journal

of Comparative and Physiological Psychology, 49(3), 269–270.

https://doi.org/10.1037/h0040634

Sidman, M. (1958).

By-products of aversive control. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of

Behavior, 1(3), 265-280. 10.1901/jeab.1958.1-265

Silva, J.R. (2007).

Sobrealimentación inducida por la ansiedad. Parte I: evidencia conductual,

afectiva, metabólica y endócrina. Terapia Psicológica, 25(2), 141-154.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-48082007000200005

Simon, N.M. (2009)

Generalized anxiety disorder and psychiatric comorbidities such as depression,

bipolar disorder, and substance abuse. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry,

70(2), 10-14.

Scherer, K.R.

(2000). Psychological models of emotion. In J.C. Borod (Ed.). The

neuropsychology of emotion (pp. 137-162). Oxford University Press.

Skinner, B. F.

(1931). The concept of the reflex in the description of behavior. Journal of

General Psychology, 5, 427–458.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00221309.1931.9918416

Skinner, B. F.

(1935). The generic nature of the concepts of stimulus and response. Journal

of General Psychology, 12, 40–65.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00221309.1935.9920087

Skinner, B. F.

(1938). The behavior of organisms: an experimental analysis. Appleton-Century.

Szasz, T. (2019). Esquizofrenia.

El símbolo Sagrado de la psiquiatría. Ediciones Coyoacán. (Original work

published 1961)

Szasz, T. (1976). El

mito de la enfermedad mental. Amorrortu.

Szasz, T. (1978). The

Myth of Psychotherapy: Mental Healing as Religion, Rhetoric, and Repression.

SUP.

Tomasini, A. (1988).

El pensamiento del último Wittgenstein. Trillas.

Tomasini, A. (1995).

Ensayos de filosofía de la Psicología. Universidad de Guadalajara.

Tomasini, A. (1996).

Enigmas filosóficos y filosofía wittgensteiniana. Editorial

Interlinea.

Tomasini, A. (2008).

Discusiones Filosóficas. Plaza y Valdés.

Tomasini, A. (2016).

Filosofía, Conceptos Psicológicos y Psiquiatría. Herder.

Turbayne, M. (1962).

The myth of metaphor. Yale University Press.

Watson, J. &

Rayner, R. (1920). Conditioned emotional reactions. Journal of Experimental

Psychology, 3(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0069608

Wittgenstein, L.

(1953). Philosophical Investigations. Blackwell

Wundt, W. (2019). Outlines

of Psychology. Williams and Norgate; Wilhelm Engelmann. (Original work

published 1897)