https://doi.org/10.24016/2023.v9.358

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Psychometric properties of the Mexican version of the Intolerance of Uncertainty

Scale: The IUS-12M

Propiedades psicométricas

de la versión mexicana de la Escala de Intolerancia a la Incertidumbre: La

IUS-12M

Alejandrina

Hernández-Posadas1,2*, Anabel De la Rosa-Gómez 1, Miriam

J.J. Lommen2, Theo K. Bouman2, Juan Manuel Mancilla-Díaz1,

Adriana del Palacio González3

1 National

Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico City, Mexico.

2 University

of Groningen, Groningen, Netherlands.

3 Aarhus

University, Aarhus, Denmark.

* Correspondence: alejandrina.hernandez@iztacala.unam.mx

Received: August 25, 2023 |

Revised: November 11, 2023 | Accepted: December 18, 2023 | Published

Online: 29 December, 2023.

CITE IT AS:

Hernández-Posadas, A., De la Rosa-Gómez,

A., Lommen, M., Bouman, T.,

Mancilla-Díaz, J., & Valdés, D. (2023). Psychometric properties of the Mexican

version of the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale: The IUS-12M. Interacciones, 9, e358. https://doi.org/10.24016/2023.v9.358

ABSTRACT

Background: The Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale short version

(IUS-12) has proven to be a robust self-report measure to assess intolerance of

uncertainty. While previous psychometric analyses of the IUS-12 have

established a stable two-factor structure corresponding to the prospective and

inhibitory factors of intolerance of uncertainty, recent studies suggest that

the bifactor model may better explain its factor structure. Objective: The

aim of the current study was to culturally adapt and validate the IUS-12 in a

Mexican population. Method: The aim of the current study was to

culturally adapt and validate the IUS-12 in a Mexican population. Result:

Confirmatory factor analyses supported a bifactor model and a good internal

consistency. Invariance testing indicated partial invariance across women and

men. Convergent validity tests showed that the IUS-12 was related to measures

of worry, as well as depression and anxiety. Conclusion: These findings

provide evidence for the reliability and validity of the adapted version of the

IUS-12 in Mexico.

Keywords: Psychometric Properties, Intolerance of Uncertainty, Confirmatory Factor

Analysis, Mexico, Reliability.

RESUMEN

Introducción: La Escala de Intolerancia a

la Incertidumbre versión corta (IUS-12) ha demostrado ser una medida robusta de

autoinforme para evaluar la intolerancia a la incertidumbre. A pesar de que los

análisis psicométricos anteriores de la IUS-12 han establecido una estructura

de dos factores correlacionados que corresponde a los factores prospectivo e

inhibitorio de la intolerancia a la incertidumbre, estudios recientes sugieren

que el modelo bifactorial puede explicar mejor su estructura factorial. Objetivo: El objetivo del estudio actual fue adaptar culturalmente y

validar la IUS-12 para su uso en la población mexicana. Método: El estudio se llevó a cabo con una muestra comunitaria no probabilística

por conveniencia de 405 adultos con edades comprendidas entre los 18 y 70 años.

Resultados: Los análisis factoriales

confirmatorios respaldaron un modelo bifactor y una

buena consistencia interna. Las pruebas de invarianza indicaron invarianza

parcial entre mujeres y hombres. Las pruebas de validez convergente mostraron

que la IUS-12 estaba relacionada con medidas de preocupación, así como con

depresión y ansiedad. Conclusión: Estos hallazgos proporcionan evidencia de la

fiabilidad y validez de la versión adaptada de la IUS-12 en México.

Palabras claves:

Propiedades

Psicométricas, Intolerancia a la Incertidumbre, Análisis Factorial

Confirmatorio, México, Confiabilidad.

BACKGROUND

Intolerance of uncertainty is a dispositional inability of an individual

to withstand the aversive response triggered by the perceived absence of

relevant, key or sufficient information, and sustained by the associated

perception of uncertainty (Carleton, 2016). Individuals with high levels of

intolerance of uncertainty tend to interpret uncertainty negatively (Carleton

et al., 2007). Uncertainty may contribute to maladaptive emotional, cognitive

and behavioral processes that are associated with emotional distress (Boswell

et al., 2013; Buhr & Dugas, 2009). Perceptions of uncertainty may increase

avoidance of uncertain situations to prevent feelings of anxiety or discomfort,

however, also consequently maintaining negative perceptions of uncertainty,

resulting in a vicious cycle (Carleton, 2016).

The concept of intolerance of uncertainty was initially proposed as a

specific vulnerability factor for generalized anxiety disorder (Ladouceur et

al., 1999). However, a substantial number of studies have provided evidence

that intolerance of uncertainty is a transdiagnostic construct, associated with

symptoms of multiple disorders. Evidence has demonstrated that intolerance of

uncertainty is significantly related to a variety of anxiety and depressive

disorders in both clinical and non-clinical samples (Carleton, 2016; Carleton

et al., 2012; McEvoy & Mahoney, 2012). More specifically, robust and

significant associations have been identified between intolerance of

uncertainty and symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder (Gentes & Ruscio,

2011; McEvoy et al., 2019; McEvoy & Mahoney, 2012), social anxiety disorder

(Boelen & Reijntjes,

2009; McEvoy & Mahoney, 2012), obsessive compulsive disorder (Holaway et

al., 2006; McEvoy & Mahoney, 2012), panic disorder (Carleton et al., 2013),

post-traumatic stress disorder (Fetzner et al., 2013), eating disorders

(Sternheim et al., 2011), and depression (McEvoy et al., 2019; McEvoy &

Mahoney, 2012).

Moreover, researchers have explored whether intolerance of uncertainty

could be a relevant target for treatment. Oglesby et al. (2017) examined the

efficacy of a cognitive bias modification intervention focused on intolerance

of uncertainty. The results indicated significant changes in intolerance of

uncertainty from pre-to-post treatment, as well as significant reductions at

the one-month follow-up. Likewise, a number of studies found associations

between changes in intolerance of uncertainty and reduction in

psychopathological symptoms, such as generalized anxiety disorder (Dugas et

al., 2003; McEvoy & Erceg-Hurn, 2016; Van Der Heiden et al., 2012), social

anxiety disorder (McEvoy & Erceg-Hurn, 2016), anxiety and depression

(Boswell et al., 2013; Dugas et al., 2003). Particularly, Boswell et al. (2013)

conducted a clinical trial using the Unified Protocol for the Transdiagnostic

Treatment of Emotional Disorders (Barlow et al., 2010), and found a significant

decrease in intolerance to uncertainty over the course of the treatment as well

as reductions in anxiety and depression symptoms post-treatment.

Intolerance of uncertainty has been defined as a multidimensional

construct (Buhr & Dugas, 2002; Carleton et al., 2007; Freeston et al.,

1994; Norton, 2005). One measure that has been widely used to assess this

construct is the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale (IUS) (Del Valle et al.,

2020; Mary E. Oglesby et al., 2016; Paulus et al., 2015; Toro et al., 2018; Voitsidis et al., 2021). The IUS was first developed in

French to assess emotional, cognitive, and behavioral reactions to uncertainty

in everyday life situations (Freeston et al., 1994). The IUS consists of 27

items representing five different factors; however, one item did not load on

any factor and four items loaded on more than one factor. The back-translated

English version of the IUS found evidence for a four-factor structure, however

six items loaded on multiple factors (Buhr & Dugas, 2002). Subsequent

analysis of the IUS factor structure resulted in five and six factor solutions,

with multiple factor loadings suggesting redundancy within the items (Norton,

2005). As a result, Carleton et al. (2007) developed a shorter 12-item version

that highly correlated with the 27-item version (r=.96), had excellent internal

consistency (α=.91), and a stable two-factor structure. The Intolerance of

Uncertainty Scale short version (IUS-12) has proven to be a robust and stable

measure of intolerance of uncertainty, representing two factors: prospective

and inhibitory uncertainty. The prospective factor has an anticipatory

cognitive nature and is conceptualized as a desire for predictability of future

events (e.g., One should always look ahead so as to avoid surprises). The

inhibitory factor refers to behavioral paralysis and impaired functioning due

to uncertainty (e.g., The smallest doubt can stop me from acting) (Carleton et

al., 2007).

The IUS-12 has been replicated in several studies supporting the correlated

two-factor structure in diverse populations. Carleton et al. (2007) analyzed

the factor structure in two undergraduate samples (Canada and USA) and found

that the 12-item two-factor model provided the best fit for the data with

excellent internal consistency (α=.91), and acceptable convergent validity with

measures of depression (r=.56), anxiety (r=.57), worry (r=.54), and generalized

anxiety (r=.61). Khawaja & Yu (2010) examined the psychometric properties

of the IUS-12 in a clinical and non-clinical sample. Results indicated good

internal consistency (clinical sample α=.87 and non-clinical sample α=.92),

convergent validity with worry (r=.54) and trait anxiety (r=.60), and

difference in the total scores of the clinical and non-clinical sample. McEvoy &

Mahoney (2011) assessed the latent structure of the IUS-12 in a treatment

seeking sample with anxiety and depression. Again, the two-factor solution

showed the best fit, the total scale demonstrated good internal consistency

(α=.93), and convergent validity with worry (r=.56), neuroticism (r=.55), and

depression (r=.52).

Moreover, the IUS-12 has been translated, culturally adapted, and

validated in different countries. Helsen et al. (2013) examined and compared

both the IUS-12 and IUS Dutch versions. Results indicated that the IUS-12

two-factor model provided the best fit, internal consistency for the total

score was adequate (α=.83), and convergent validity with worry (r=.52), and

depression (r=.48). Lauriola et al. (2016)

back-translated the English version of the IUS-12 to Italian and tested

alternative models (two-factor, second-order and bi-factor). Results

demonstrated that the bifactor model had the best model fit with an internal

consistency of ω=.86 and ωH=.75 for the general

factor, ω=.75 for the prospective and ω=.75 inhibitory factor. Kumar et al.

(2021) assessed the factor structure of the Hindi version comparing a

single-factor, correlated two-factor, truncated bifactor, and full bifactor.

The bifactor model provided the best model fit of the data with an internal

consistency of ω=.85. Kretzmann & Gauer (2020) translated to Portuguese the

IUS-12 for the Brazilian population. The confirmatory factor analysis

demonstrated that the original two-dimensional structure had a good fit,

acceptable internal consistency (α=.88), and convergent validity with

generalized anxiety (r=.58), worry (r=.68), and obsessive compulsion (r=.58).

Pineda-Sánchez (2018) translated the IUS-12 to Spanish and examined its

psychometric properties in a Spanish sample. Confirmatory factor analysis

demonstrated that the correlated two-factor model provided the best model fit,

with an excellent internal consistency of (α=.91), and convergent validity with

measures of worry (r=.56), obsessive compulsive symptoms (r=.42), and anxiety

(r=.38).

The increasing evidence base suggests that intolerance of uncertainty

plays a significant role in the development, maintenance, and treatment of

various disorder symptoms, highlighting the importance of reliable and valid

measures for this construct. However, despite the broad importance of

intolerance of uncertainty as a transdiagnostic construct, there is only one

study on Spanish versions and no studies to the date were performed in a

Mexican population. Therefore, the aim of the current study was to culturally

adapt and validate the IUS-12 for the Mexican population. Confirmatory factor

analyses were conducted to evaluate the factor structure of the scale in a

Mexican community sample. Moreover, reliability estimates and convergent

validity were examined. It was hypothesized that the Mexican version would

replicate the bifactor structure (Carleton et al., 2007), have good internal

consistency and partial invariance. Likewise, intolerance of uncertainty was

hypothesized to be positively and strongly related to worry, and moderately

related to depression and anxiety.

METHOD

Design

The present study has an instrumental design, as it focuses on examining the psychometric properties of a measurement instrument (Ato et al., 2013).

Participants

The study consisted of a convenience non-probabilistic community sample of 405 adults between 18 and 70 years of age (M=34.19, SD=12.9) recruited as part of the screening for a larger online intervention study for emotional disorders. In this sample, 234 were women (57.8%), while 171 were men (42.2%). Most participants were single (55.6%), while 21.5% married, 12.6% cohabitating, 4.2% separated, 3.2% divorced, and 2.2% otherwise. In terms of education level, 60.0% had completed an undergraduate degree 15.8% high school, 15.1% master’s degree, and 9.1% otherwise. The majority of the participants (84.7%) lived in Mexico City’s metropolitan area. Participants with incomplete data were considered to be dropouts.

Instruments

Sociodemographic data. A sociodemographic data questionnaire was developed requesting

information on age, sex, marital status, level of education, and place of

residence.

Intolerance of uncertainty

scale, short version (IUS-12; Carleton et al.,

2007). The IUS-12 is a 12-item self-report measure that assesses individuals’

ability to tolerate uncertainty about ambiguous future events. The IUS-12

includes two factors: prospective intolerance of uncertainty (PIU) (i.e.,

perceptions of threat related to future uncertainty) and inhibitory intolerance

of uncertainty (IIU) (i.e., behaviors indicating apprehension about

uncertainty). Individuals rate items on a five-point Likert scale (1=“not at all characteristic of me” to 5=“entirely

characteristic of me”). A back-translated version in Spain yielded a two-factor

solution similar to the original, with adequate internal consistency for both

the total scale (α=.92) and subscales (PIU, α=.89; IIU, α=.91) (Pineda-Sánchez,

2018).

Penn State Worry

Questionnaire (PSWQ-11; Meyer et al.,

1990). The PSWQ measures the frequency and intensity of worry. The brief

version (PSWQ-11) was adapted and validated in Spain in which the 5 items

negatively worded were eliminated, thus consisting of 11 Likert-type items

(with options from “nothing” to “a lot”) (Sandín et

al., 2009). In the Mexican population the PSWQ-11 obtained a better model fit

than the original 16-item (PSWQ-16) and obtained adequate internal consistency

coefficient with an α=.88 (Padros-Blazquez et al.,

2018).

Beck Depression

Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck et al.,

1996). The BDI-II is a self-report questionnaire to assess behaviors,

attitudes, and feelings that characterize depression within the last two weeks.

It includes 21 symptom items that use a 4-point scale (scored 0-3) that reflect

increasing symptom frequency or severity. Total scores can range from 0-63 with

the following cut-offs points: 0-13 minimally depressed, 14-19 mildly

depressed, 20-28 moderately depressed, and 29-63 severely depressed. The BDI-II

was adapted and validated in Mexico showing an adequate internal consistency

with student (α=.92) and community (α=.87) samples (González et al., 2015).

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Beck et al., 1988). The BAI is a 21-item self-report measure of

the severity of common affective, cognitive, and somatic symptoms of anxiety.

Items have four response options ranging from 0 “not at all” to 3 “severely”.

The cut-off points are: 0-5 minimal anxiety, 6-15 mild anxiety, 16-30 moderate

anxiety and 31-63 severe anxiety. Validation in Mexican population yielded

adequate internal consistency, with α=0.84 in the student sample and α=0.83 in

the community sample, and a high test-retest reliability coefficient r=0.75.

The four-factor structure of the scale is consistent with that reported in

previous studies and the original version (Robles et al., 2001).

Procedure

The Mexican adaptation of the IUS-12 was based on the items from the

Spanish version (Pineda-Sánchez, 2018). Although the Spanish and the Mexican populations

share similarities in language, it was necessary to make adaptations due to

cultural differences in expressions and words that vary from one country to

another and could potentially cause confusions. For example, in item 6 “No soporto que me cojan por sorpresa” the Spanish version

uses the verb “cojan”, which in Mexico has a sexual connotatiom. Therefore, this item was changed to “No soporto que me agarren por sorpresa”. Likewise, other

items were adapted to reflect a more colloquial form of Mexican Spanish.

Additionally, response options were increased from five to six because

psychometric precision has been found to be low with five or fewer options and

remain stable after six (Simms et al., 2019). The items were revised by three

researchers and university professors from the National Autonomous University

of Mexico (UNAM) with experience in emotional and trauma disorders (DeVellis,

2016; Furr, 2011; Rubio et al., 2003). The battery of instruments was set up on

the SurveyMonkey online survey platform and the participants were recruited

through ads in social media.

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were estimated using SPSS-25 package and AMOS-23.

First, an item variability analysis was performed. Second, multivariate

normality was estimated with the Mardia’s coefficient

that according to Bollen (1989) when Mardia’s

coefficient is less than p(p+2), where p is the number of observed variables,

the sample shows multivariate normality. Third, to examine the factor structure

of the IUS-12 Mexican adaptation a Confirmatory Factor Analysis was performed.

Model parameters were estimated with maximum likelihood estimation. This method

is applicable when the items analyzed have a minimum of five response options

as is the present case in this study (Rhemtulla et

al., 2012). This allows a simpler factor model to be applied, rather than a

more complex one such as those using polychoric correlations and least squares

estimators (e.g., WLSMV). Model fit was assessed considering the following fit

indices: Chi square (χ2), relative Chi square (χ2/df), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis

index (TLI), Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), and Root of the

mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). An appropriate model fit was

considered when χ2/df was between 1 and 3,

CFI and TLI≥.95, SRMR≤. 08, and RMSEA≤.06 (Bagozzi & Yi, 2011; Hu &

Bentler, 2009). The estimated sample size considering a CFI of 0.95,

significance level (α) of 0.05 and a statistical power of 0.80, was 279

participants (Arifin, 2023). Fourth, to assess the reliability of the scale, we

calculated the omega hierarchical for the IUS general factor (ωH) and omega hierarchical subscale (ωHS)

for the specific factors (Prospective and Inhibitory). Furthermore, in order to

determine whether a bifactor structure with a strong general factor should be

represented as a unidimensional or multidimensional (bifactor). Unidimensionality of a scale could be interpreted when

Omega hierarchical values for the general factor are greater than .70, the

explained common variance (ECV) values are greater than .60, and the percentage

of uncontaminated correlations (PUC) values are lower than .80 (Reise et al.,

2012; Rodriguez et al., 2016). Next, to assess whether the model was invariant

across sexes, a multi-group analysis was conducted, a strong invariance is

supported when ΔCFI≤0.01, ΔRMSEA≤0.015 and Δχ2 results with p>.05

(Cheung & Rensvold, 2002). Finally, to assess convergent validity Pearson's

correlations were calculated between IUS-12 and the average scores of worry,

anxiety and depression symptoms.

Ethics Aspects

This study was part of a larger research project “Suitability, Clinical

Utility and Acceptability of an Online Transdiagnostic Intervention for

Emotional Disorders and Stress-related Disorders in Mexican Sample: A

Randomized Clinical Trial” which was approved by the Ethics Committee of the

Faculty of Higher Studies Iztacala UNAM (CE/FESI/

082020/1363). All participants read and agreed to an electronic consent before

completing the self-report questionnaires online.

RESULTS

Preliminary

analysis

Prior to data analyses, the means, standard deviation,

skewness, and kurtosis were calculated. The standard deviations ranged from

1.26 to 1.49, indicating minimal variation. None of the skewness and kurtosis

indices were out of range (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013). Descriptive

statistics for the sample are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Intolerance of uncertainty

Scale 12-item Mexican version (IUS-12M) Items means, standard deviations,

skewness, kurtosis.

|

Item |

Mean |

S.D. |

Skewness |

Kurtosis |

|

1. Unforeseen

events upset me greatly. |

4.05 |

1.39 |

-0.49 |

-0.19 |

|

2. It frustrates

me not having all the information I need. |

4.51 |

1.27 |

-0.78 |

0.47 |

|

3. One should

always look ahead so as to avoid surprises. |

4.27 |

1.28 |

-0.61 |

0.2 |

|

4. A small,

unforeseen event can spoil everything, even with the best of planning. |

3.87 |

1.39 |

-0.21 |

-0.53 |

|

5. I always

want to know what the future has in store for me. |

3.96 |

1.48 |

-0.3 |

-0.64 |

|

6. I can’t

stand being taken by surprise. |

3.76 |

1.35 |

-0.27 |

-0.3 |

|

7. I should

be able to organize everything in advance. |

4.23 |

1.31 |

-0.56 |

0.11 |

|

8.

Uncertainty keeps me from living a full life. |

4.1 |

1.5 |

-0.39 |

-0.64 |

|

9. When it’s

time to act, uncertainty paralyses me |

3.49 |

1.46 |

-0.08 |

-0.67 |

|

10. When I am

uncertain I can’t function very well. |

4.2 |

1.32 |

-0.42 |

-0.12 |

|

11. The

smallest doubt can stop me from acting. |

3.64 |

1.45 |

-0.14 |

-0.68 |

|

12. I must

get away from all uncertain situations. |

3.71 |

1.33 |

-0.14 |

-0.26 |

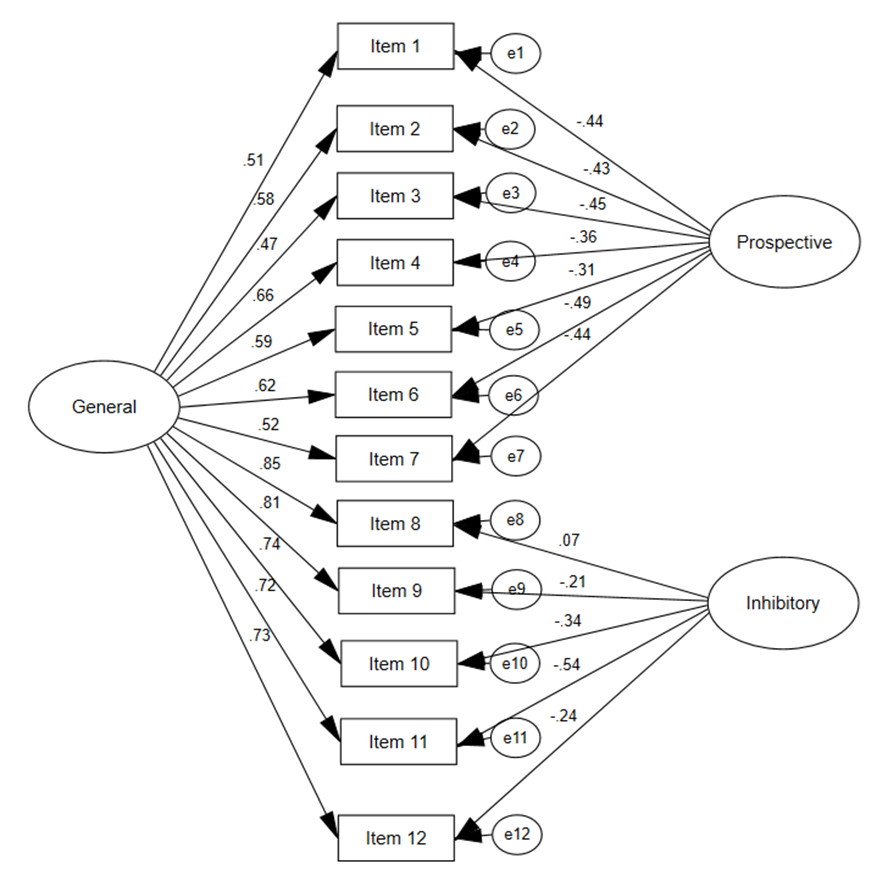

Confirmatory factor

analysis

Multivariate normality of the data was estimated by

obtaining Mardia's coefficient of multivariate

kurtosis, which was 35.452, a lower value to cutoff criteria indicated by

Bollen (1989) that for 12 observed variables would be: 12(12+2) =168.

Subsequently, a confirmatory factor analysis was performed in order to test the

factor structure of the scale. Initially, we tested the correlated two-factor

model, model fit indices indicated an acceptable model fit (see Table 2). However,

correlation between the factors was high (Φ=.77). Therefore, a unidimensional

factor model was examined, which resulted in a poor model fit. Finally, a

bifactor model was estimated with results that indicated it had the best model

fit. As observed in Figure 1, standardized factor loadings for the general

factor were positive, while those for the specific factors negative, except for

item 8. may occur due to participants interpreting it differently, as it

reflects a slightly distinct aspect of uncertainty compared to the preceding

items. These results support that the factor structure of the IUS-12M can be

conceptualized as a general factor and a prospective and inhibitory specific

factor.

Table 2. Model fit measures for the

competing models.

|

Model |

χ2(df) |

p |

χ2/df |

CFI |

TLI |

SRMR |

RMSEA |

|

Two correlated factors |

153.555 (53) |

<.001 |

2.897 |

0.962 |

0.952 |

0.047 |

0.069 |

|

Unidimensional |

402.246 (54) |

<.001 |

7.579 |

0.865 |

0.835 |

0.076 |

0.128 |

|

Bifactor |

89.823 (42) |

<.001 |

2.139 |

0.982 |

0.971 |

0.03 |

0.053 |

Figure 1. Standardized factor loadings

for the bifactor model of the 12-item Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale Mexican

version (IUS-12M)

Reliability

Reliability analysis of the bifactor model was

estimated through the omega and omega hierarchical coefficients, which are more

appropriate index of reliability for bifactor models (Rodriguez et al., 2016).

The omega of the scale (ω=0.91) represents the variance in the total score

without differentiating variance from the general or specific factors.

Additionally, we estimated the omega hierarchical which represents the

proportion of the variance explained by the general factor after controlling

the variance accounted for the specific factors (ωH=.80).

The unique variance of each specific factors after controlling for the variance

accounted by the general factor were ωHS=.30 for the

Prospective factor and ωHS=.09 for the Inhibitory

factor. According to the explained common variance (ECV), 75% of the common

variance was attributable to the general factor of IUS-12. Given that an ECV value

was greater than .60, the percentage of uncontaminated correlations (PUC=.53)

lower than .80, and ωH greater than .70 a

unidimensional interpretation of the scale is appropriate (Reise et al., 2012).

Invariance

To examine whether the bifactor model was invariant

across sexes (women, men) and age (young adults, older adults), a multi-group

analysis was conducted. First, the configurational or baseline model that

allowed the factor loadings to be freely estimated was compared with a metric

invariance model that constrained the factor loadings across the two groups,

then this model was compared with a scalar invariance model that constrained

the intercepts in addition to the factor loadings, and finally this model was

compared with a strict invariance model that also constrained the residuals

(see Table 3). The test for sex invariance showed equivalence of the factor

structure between men and women, except for one of the parameters of the

invariance model. In the case of age invariance, the test showed equivalence in

factor loading. In this case, a partial invariance would be assumed (Dimitrov,

2010), however it has been recognized that strict invariance tests are

excessively restrictive (Bentler, 2004).

Table 3. Measurement invariance.

|

Group |

Invariance |

χ2(df) |

χ2/df |

CFI |

RMSEA (90%

IC) |

Δχ2 |

ΔCFI |

ΔRMSEA |

|

women and men |

Configural |

141.037 (86) |

1.64 |

0.978 |

0.040

(.028-.051) |

|||

|

Metric |

146.811 (107) |

1.372 |

0.984 |

0.030

(.017-.042) |

5.774

(p=.999) |

0.006 |

-0.01 |

|

|

Scalar |

202.955 (119) |

1.706 |

0.967 |

0.042

(.032-.052) |

56.144

(p<.01) |

-0.017 |

0.012 |

|

|

|

Strict |

221.706 (133) |

1.667 |

0.965 |

0.041

(.031-.050) |

18.75

(p=.175) |

-0.002 |

-0.001 |

|

Age group |

Configural |

150.901 (86) |

1.755 |

0.975 |

0.043(.032-.055) |

|||

|

Metric |

162.504 (107) |

1.519 |

0.979 |

0.036

(.024-.047) |

11.603

(p=.950) |

0.004 |

-0.007 |

|

|

Scalar |

219.587 (119) |

1.845 |

0.961 |

0.046

(.036-.055) |

57.084

(p<.01) |

-0.018 |

0.01 |

|

|

|

Strict |

251.033 (133) |

1.887 |

0.955 |

0.047

(.038-.056) |

31.445

(p=.005) |

-0.006 |

0.001 |

Convergent validity

According to the nomological network of intolerance of

uncertainty, this construct contributes to maladaptive cognitions such as

worry, and avoidance behaviors present in emotional disorders (Boswell et al.,

2013). Several studies have shown that intolerance of uncertainty is a

maintenance factor due to its positive associations with a variety of

psychological disorders such as depression and anxiety disorders (Carleton et

al., 2012). The IUS-12 is expected to have a positive relation to anxiety,

depression and worry measures. The IUS-12M was correlated with measures of

anxiety (BAI), depression (BDI-II), and worry (PSWQ-11). Results indicated the

IUS-12M correlated strongly with PSWQ-11 (r=.685, p<0.001) and BDI-II

(r=.582, p<0.001), and moderately with the BAI (r=.439, p<0.001). These

results support the convergent validity of the scale.

DISCUSSION

After culturally adapting the individual items, we performed

confirmatory factor analyses with competing measurement models (correlated

two-factors, unidimensional, and bifactor). First, we estimated the correlated

two-factor solution mirroring the English versions with both clinical and

non-clinical samples (Carleton et al., 2007; Khawaja & Yu, 2010; McEvoy

& Mahoney, 2011), results indicated an adequate model fit. However, given

that there was a strong association between the two factors, a unidimensional

factor structure was also examined, but had a poorer model fit, also in line

with previous studies (Carleton et al., 2007; Shihata

et al., 2018). Finally, we estimated a bifactor model, which resulted in the

best model fit for the data. The bifactor model solution was also supported in

recent findings for the IUS-12 (Kumar et al., 2021; Lauriola

et al., 2016; Shihata et al., 2018). Therefore, the

results indicated that the structure of the IUS-12M is better explained by a

bifactor solution consisting of a general factor and two specific factors

(prospective and inhibitory uncertainty).

The IUS-12M had a good internal consistency for the general factor,

which explained most of the common variance of the model. The reliability of

the IUS-12M was quite similar to previous bifactor models such as the Italian (Lauriola et al., 2016) and the Indian (Kumar et al., 2021)

versions. Previous research has suggested the interpretation and assessment of

the prospective and inhibitory factors, while other studies indicate that a

total score is more appropriate. However, these affirmations have not been

psychometrically supported (Hale et al., 2016). The inclusion of bifactor

modeling is a method for testing whether the subscales contribute sufficient

variance after controlling for a general factor, or if the scale represents a

single underlying construct (Rodriguez et al., 2016). Given that the IUS-12M

general factor explained a greater amount of common variance and the

prospective and inhibitory specific factors were not contributing substantially

to the reliability of the total score, the use of the total score is a more

appropriate measure for assessments. This result was also in line with other

bifactor models of the scale (Hale et al., 2016; Kumar et al., 2021; Lauriola et al., 2016).

Regarding scale invariance, many researchers expect psychometric

instruments to assess similar constructs in women and men, therefore rarely

testes invariance, resulting in bias in research findings going unnoticed

(Steyn & de Bruin, 2020). Particularly for the IUS-12 there is limited

evidence testing for sex invariance, however, the existing evidence report

partial invariance (Helsen et al., 2013; Kumar et al., 2021; Lauriola et al., 2016). For the Mexican version, despite a

slight sex imbalance in the sample, the bifactor model was stable across women

and men as indicated by both factor structure and factor loadings. On the other

hand, age invariance only demonstrated a stable factor structure, which could

potentially indicate differences in comprehension of the items between age

groups. However, there is insufficient evidence of age invariance in the

construct of intolerance of uncertainty, suggesting a need for further

exploration.

To establish the convergent validity, the IUS-12M was correlated with

measures of worry, depression, and anxiety. According to the nomological

network, the construct of intolerance of uncertainty should be positively and

strongly related to worry, and moderately related to depression and anxiety.

This hypothesized pattern was supported for all three measures in the present

study. However, the correlation was stronger for depression than for anxiety.

This could be explained by previous findings that trait anxiety has a stronger

relation with intolerance of uncertainty than state anxiety (Khawaja & Yu,

2010). The correlation analyses indicated that participants with high scores of

intolerances of uncertainty also had high scores of worry,

depression, and anxiety, which is consistent with previous studies (Helsen et

al., 2013; Kretzmann & Gauer, 2020; McEvoy & Mahoney, 2011;

Pineda-Sánchez, 2018). Overall, correlation patterns between the IUS-12M and

worry, depression, and anxiety supported the convergent validity of the Mexican

adaptation. Although, we examined convergent validity in this study, it is

important to note that future studies should also examine discriminant validity

to further strengthen the validity evidence of the measure.

Limitations

The findings in this study should be interpreted in the context of

various limitations, mostly concerning the sample characteristics. Despite

great efforts to seek diverse sample, the majority of participants lived in the

metropolitan area of Mexico City and approximately 60% has an undergraduate

degree, Mexico is a culturally diverse country with an overall low attainment

of tertiary education (i.e., less than 25% of the population hold an

undergraduate degree; OECD, 2019). Further, the sample consisted of

non-clinical individuals. Therefore, the present findings might not generalize

fully to less educated individuals or those living in other regions. However,

concerning the non-clinical characteristics, previous research found stable

psychometric properties across clinical and non-clinical samples (Khawaja &

Yu, 2010). In contrast, compared to other adaptations based exclusively on

young student samples (e.g., Kumar et al., 2021), the results from this study

derive from a wider age range sample. Finally, while the bifactor model emerged

as the best-fitting model in our sample, its applicability to the Spanish

version cannot be definitively asserted. Therefore, future studies should

investigate whether the bifactor model remains the best-fitting option for the

Spanish version. Despite the limitations of the sample, these findings align

well with international research, which may be indicative of robust

psychometric properties for the current Mexican adaptation. That said, future

research should aim for more representative samples. In sum, the IUS-12M

demonstrated evidence of internal consistency, invariance between sexes, and

convergent validity.

Clinical implications

The findings of this study hold important

clinical implications for understanding and addressing intolerance of

uncertainty within the Mexican population. The validation of the IUS-12M in

this cultural context provides mental health professionals with a valuable

instrument for assessing intolerance of uncertainty, a transdiagnostic factor

that plays a significant role in the development, maintenance, and treatment of

emotional disorders. Furthermore, the identification of a bifactor model

provides clinicians with better understanding of intolerance of uncertainty,

which can guide targeted interventions for the diverse facets of this

construct. Additionally, the IUS-12M holds promise in offering valuable

insights for the development of public health policies and programs dedicated

to preventing and treating emotional disorders.

Conclusion

The Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale short version (IUS-12) has proven

to be a robust self-report measure to assess intolerance of uncertainty.

Previous psychometric analyses of the IUS-12 have demonstrated a stable

two-factor structure, corresponding to prospective and inhibitory factors of

intolerance of uncertainty. However, recent studies support the bifactor model

to best explain the factor structure of the IUS-12. This study culturally

adapted and validated the IUS-12 in a Mexican community sample of 405 adults.

Confirmatory factor analyses indicated that the bifactor model had the best

model fit. Internal consistency of the general factor was excellent ωH=0.80. Invariance testing indicated partial invariance

across women and men. With regard to the convergent validity, the results

showed that the IUS-12M was related to measures of worry, depression and

anxiety. These findings support the reliability and validity of the adapted

version of the IUS-12 in Mexican population.

ORCID

Alejandrina

Hernández-Posadas: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5753-9785

Anabel

De la Rosa-Gómez: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3527-1500

Miriam J.J. Lommen:

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8845-4338

Theo K. Bouman: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9066-5553

Juan

Manuel Mancilla-Díaz: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7259-3667

Adriana

del Palacio González: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6523-4639

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

Alejandrina

Hernández-Posadas: conceptualization, methodology, analysis, writing - original

draft, writing - review & editing.

Anabel De la

Rosa-Gómez: conceptualization, methodology, analysis, writing - review &

editing.

Miriam J.J. Lommen: analysis,

writing - review & editing.

Theo K. Bouman: analysis,

writing – review & editing.

Juan Manuel

Mancilla-Díaz: analysis, writing - review & editing.

Adriana del Palacio

González: analysis, writing -

review & editing.

FUNDING

SOURCE

This research was supported by the Consejo

Nacional de Humanidades, Ciencias

y Tecnologías (CONAHCYT) provided through the

scholarship awarded to the first author to carry out doctoral studies:

scholarship number 751969 and scholar number CVU: 697623.

CONFLICTO DE

INTERESES

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

To the Master´s and Doctorate Program in Psychology of the National

Autonomous University of Mexico. To the University of Groningen. This work was

supported by UNAM-PAPIIT (IT300721). To Dr. Nazira Calleja for their valuable

assistance in translating the scale items.

REVIEW

PROCESS

This study has been reviewed by external peers in double-blind mode.

The editor in charge was Giuliana Salazar. The review process is included as

supplementary material 1.

DATA

AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data will be made available on request.

STATEMENT ON

THE USE OF GENERATIVE ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

No artificial intelligence-generated tools were used in the creation of

the manuscript.

DISCLAIMER

The authors are responsible for all statements made in this article.

REFERENCES

Arifin, W. N. (2023). Sample size

calculator (web). http://wnarifin.github.io

Ato, M., López, J. J., &

Benavente, A. (2013). A classification system for research designs in

psychology. Anales de Psicología / Annals of Psychology, 29(3),

1038–1059. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.29.3.178511

Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (2011).

Specification, evaluation, and interpretation of structural equation models. Journal

of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(1), 8–34.

https://doi.org/10.1007/S11747-011-0278-X

Barlow, D. H., Ellard, K. K., &

Fairholme, C. P. (2010). Unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of

emotional disorders: Workbook. Oxford University Press.

Beck, A. T., Epstein, N., Brown, G.,

& Steer, R. A. (1988). An Inventory for Measuring Clinical Anxiety:

Psychometric Properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56(6),

893–897. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.56.6.893

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., &

Brown, G. K. (1996). Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II.

Psychological Corporation.

Bentler, P. M. (2004). EQS 6.1

structural equations program. Multivariate Software.

Boelen, P. A., & Reijntjes, A. (2009). Intolerance of

uncertainty and social anxiety. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 23(1),

130–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.04.007

Bollen, K. A. (1989). Structural

equations with latent variables. John Wiley & Sons.

Boswell, J. F., Thompson-Hollands,

J., Farchione, T. J., & Barlow, D. H. (2013). Intolerance of Uncertainty: A

Common Factor in the Treatment of Emotional Disorders. Journal of Clinical

Psychology, 69(6), 630–645. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.21965

Buhr, K., & Dugas, M. J. (2002).

The intolerance of uncertainty scale: psychometric properties of the English

version. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 40(8), 931–945.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(01)00092-4

Buhr, K., & Dugas, M. J. (2009).

The role of fear of anxiety and intolerance of uncertainty in worry: An

experimental manipulation. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47(3),

215–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2008.12.004

Carleton, N. R. (2016). Into the

unknown: A review and synthesis of contemporary models involving uncertainty. Journal

of Anxiety Disorders, 39, 30–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.02.007

Carleton, N. R., Fetzner, M. G.,

Hackl, J. L., & McEvoy, P. (2013). Intolerance of Uncertainty as a

Contributor to Fear and Avoidance Symptoms of Panic Attacks. Cognitive

Behaviour Therapy, 42(4), 328–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2013.792100

Carleton, N. R., Mulvogue, M. K.,

Thibodeau, M. A., McCabe, R. E., Antony, M. M., & Asmundson, G. J. G.

(2012). Increasingly certain about uncertainty: Intolerance of uncertainty

across anxiety and depression. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26(3),

468–479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.01.011

Carleton, N. R., Norton, M. A. P. J.,

& Asmundson, G. J. G. (2007). Fearing the unknown: A short version of the

Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 21(1),

105–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.03.014

Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B.

(2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural

Equation Modeling, 9(2), 233–255. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5

Del Valle, M., Andrés, M. L.,

Urquijo, S., Yerro Avincetto, M. M., López Morales, H., & Canet Juric, L.

(2020). Intolerance of uncertainty over COVID-19 pandemic and its effect on

anxiety and depressive symptoms. Interamerican Journal of Psychology, 54(2),

1–17. https://doi.org/10.30849/ripijp.v54i2.1335

DeVellis, R. F. (2016). Scale

development: Theory and applications. Sage Publications.

Dimitrov, D. M. (2010). Testing for

Factorial Invariance in the Context of Construct Validation. Measurement and

Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 43(2), 121–149.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0748175610373459

Dugas, M. J., Ladouceur, R., Léger,

E., Freeston, M. H., Langlois, F., Provencher, M. D., & Boisvert, J.-M.

(2003). Group Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Generalized Anxiety Disorder:

Treatment Outcome and Long-Term Follow-Up. Journal of Consulting and

Clinical Psychology, 71(4), 821–825.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.71.4.821

Fetzner, M. G., Horswill, S. C.,

Boelen, P. A., & Carleton, N. R. (2013). Intolerance of Uncertainty and

PTSD Symptoms: Exploring the Construct Relationship in a Community Sample with

a Heterogeneous Trauma History. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 37(4),

725–734. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10608-013-9531-6

Freeston, M. H., Rhéaume, J.,

Letarte, H., Dugas, M. J., & Ladouceur, R. (1994). Why do people worry? Personality

and Individual Differences, 17(6), 791–802.

https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(94)90048-5

Furr, R. M. (2011). Scale

construction and psychometrics for social and personality psychology. Sage

Publications.

Gentes, E. L., & Ruscio, A. M.

(2011). A meta-analysis of the relation of intolerance of uncertainty to

symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder, and

obsessive–compulsive disorder. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(6),

923–933. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.05.001

González, D. A., Rodríguez, A. R.,

& Reyes-Lagunes, I. (2015). Adaptation of the BDI-II in Mexico. Salud

Mental, 38(4), 237–244. https://doi.org/10.17711/SM.0185-3325.2015.033

Hale, W., Richmond, M., Bennett, J.,

Berzins, T., Fields, A., Weber, D., Beck, M., & Osman, A. (2016). Resolving

uncertainty about the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale–12: Application of

modern psychometric strategies. Journal of Personality Assessment, 98(2),

200–208.

Helsen, K., Van Den Bussche, E.,

Vlaeyen, J. W. S., & Goubert, L. (2013). Confirmatory factor analysis of

the Dutch Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale: Comparison of the full and short

version. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 44(1),

21–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2012.07.004

Holaway, R. M., Heimberg, R. G.,

& Coles, M. E. (2006). A comparison of intolerance of uncertainty in

analogue obsessive-compulsive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder. Journal

of Anxiety Disorders, 20(2), 158–174.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2005.01.002

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (2009).

Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional

criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1),

1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Khawaja, N. G., & Yu, L. N. H.

(2010). A comparison of the 27-item and 12-item intolerance of uncertainty

scales. Clinical

Psychologist,

14(3), 97–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/13284207.2010.502542

Kretzmann, R. P., & Gauer, G. (2020). Psychometric properties

of the Brazilian Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale – Short Version (IUS-12). Trends

in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, 42(2), 129–137.

https://doi.org/10.1590/2237-6089-2018-0087

Kumar, S., Saini, R., Jain, R., &

Sakshi. (2021). Confirmatory factor analysis of the Intolerance of Uncertainty

Scale (short form) in India. International Journal of Mental Health.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00207411.2021.1969321

Ladouceur, R., Dugas, M. J.,

Freeston, M. H., Rhéaume, J., Blais, F., Boisvert, J. M., Gagnon, F., &

Thibodeau, N. (1999). Specificity of generalized anxiety disorder symptoms and

processes. Behavior Therapy, 30(2), 191–207.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7894(99)80003-3

Lauriola, M., Mosca, O., &

Carleton, N. R. (2016). Hierarchical factor structure of the Intolerance of

Uncertainty Scale short form (IUS-12) in the Italian version. TPM. Testing,

Psychometrics, Methodology in Applied Psychology, 23(3), 377–394.

https://doi.org/10.4473/TPM23.3.8

McEvoy, P. M., & Erceg-Hurn, D.

M. (2016). The search for universal transdiagnostic and trans-therapy change

processes: Evidence for intolerance of uncertainty. Journal of Anxiety

Disorders, 41, 96–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.02.002

McEvoy, P. M., Hyett, M. P., Shihata,

S., Price, J. E., & Strachan, L. (2019). The impact of methodological and

measurement factors on transdiagnostic associations with intolerance of

uncertainty: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 73,

101778. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CPR.2019.101778

McEvoy, P. M., & Mahoney, A. E.

J. (2011). Achieving certainty about the structure of intolerance of

uncertainty in a treatment-seeking sample with anxiety and depression. Journal

of Anxiety Disorders, 25(1), 112–122.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.08.010

McEvoy, P. M., & Mahoney, A. E.

J. (2012). To Be Sure, To Be Sure: Intolerance of Uncertainty Mediates Symptoms

of Various Anxiety Disorders and Depression. Behavior Therapy, 43(3),

533–545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2011.02.007

Meyer, T. J., Miller, M. L., Metzger,

R. L., & Borkovec, T. D. (1990). Development and validation of the penn

state worry questionnaire. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 28(6),

487–495. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(90)90135-6

Norton, P. J. (2005). A psychometric

analysis of the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale among four racial groups. Journal

of Anxiety Disorders, 19(6), 699–707.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2004.08.002

OECD. (2019). Education at a

Glance 2019: OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing.

https://doi.org/10.1787/f8d7880d-en

Oglesby, M. E., Allan, N. P., &

Schmidt, N. B. (2017). Randomized control trial investigating the efficacy of a

computer-based intolerance of uncertainty intervention. Behaviour Research

and Therapy, 95, 50–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BRAT.2017.05.007

Oglesby, Mary E., Boffa, J. W.,

Short, N. A., Raines, A. M., & Schmidt, N. B. (2016). Intolerance of

uncertainty as a predictor of post-traumatic stress symptoms following a

traumatic event. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 41, 82–87.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.01.005

Padros-Blazquez, F.,

Gonzalez-Betanzos, F., Martinez-Medina, M. P., & Wagner, F. (2018).

Psychometric Characteristics of the Original and Brief Version of the Penn

State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ) in Mexican Samples. Actas Espanolas de

Psiquiatria, 46(4), 117–124. https://europepmc.org/article/med/30079925

Paulus, D. J., Talkovsky, A. M.,

Heggeness, L. F., & Norton, P. J. (2015). Beyond Negative Affectivity: A

Hierarchical Model of Global and Transdiagnostic Vulnerabilities for Emotional

Disorders. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 44(5), 389–405.

https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2015.1017529

Pineda-Sánchez, D. (2018). Procesos

transdiagnósticos asociados a los trastornos de ansiedad y depresivos

[Doctoral disertation, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia].

http://e-spacio.uned.es/fez/view/tesisuned:ED-Pg-PsiSal-Dpineda

Reise, S. P., Scheines, R., Widaman,

K. F., & Haviland, M. G. (2012). Multidimensionality and Structural

Coefficient Bias in Structural Equation Modeling: A Bifactor Perspective. Educational

and Psychological Measurement, 73(1), 5–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164412449831

Rhemtulla, M., Brosseau-Liard, P. E.,

& Savalei, V. (2012). When can categorical variables be treated as

continuous? A comparison of robust continuous and categorical SEM estimation

methods under suboptimal conditions. Psychological Methods, 17(3), 354–373.

https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029315

Robles, R., Varela, R., Jurado, S.,

& Páez, F. (2001). Versión mexicana del Inventario de Ansiedad de Beck:

propiedades psicométricas. Revista Mexicana de Psicología, 18(2),

211–218.

Rodriguez, A., Reise, S. P., &

Haviland, M. G. (2016). Evaluating bifactor models: Calculating and

interpreting statistical indices. Psychological Methods, 21(2), 137–150.

https://doi.org/10.1037/MET0000045

Rubio, D. M., Berg-Weger, M., Tebb, S. S., Lee, E. S.,

& Rauch, S. (2003). Objectifying content validity: Conducting a content

validity study in social work research. Social Work Research, 27(2),

94–104. https://doi.org/10.1093/swr/27.2.94

Sandín, B., Chorot, P., Valiente, R.

M., & Lostao, L. (2009). Validación española del cuestionario de preocupación

PSWQ: estructura factorial y propiedades psicométricas. Revista de

Psicopatología y Psicología Clínica, 14(2), 107–122.

https://doi.org/10.5944/rppc.vol.14.num.2.2009.4070

Shihata, S., McEvoy, P. M., &

Mullan, B. A. (2018). A bifactor model of intolerance of uncertainty in

undergraduate and clinical samples: Do we need to reconsider the two-factor

model? Psychological Assessment, 30(7), 893–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/PAS0000540

Simms, L. J., Zelazny, K., Williams,

T. F., & Bernstein, L. (2019). Does the Number of Response Options Matter?

Psychometric Perspectives Using Personality Questionnaire Data. Psychological

Assessment, 31(4), 557–566. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000648

Sternheim, L., Startup, H., &

Schmidt, U. (2011). An experimental exploration of behavioral and

cognitive–emotional aspects of intolerance of uncertainty in eating disorder

patients. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 25(6), 806–812.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.03.020

Steyn, R., & de Bruin, G. P.

(2020). An investigation of gender-based differences in assessment instruments:

A test of measurement invariance. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 46(1),

1–12. https://doi.org/10.4102/SAJIP.V46I0.1699

Tabachnick, B., & Fidell, L. S.

(2013). Using Multivariate Statistics. Pearson Education.

Toro, R., Alzate, L., Santana, L.,

& Ramírez, I. (2018). Afecto negativo como mediador entre intolerancia a la

incertidumbre, ansiedad y depresión. Ansiedad y Estres, 24(2–3), 112–118.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anyes.2018.09.001

Van Der Heiden, C., Muris, P., & Van Der Molen, H.

T. (2012). Randomized controlled trial on the effectiveness of metacognitive therapy

and intolerance-of-uncertainty therapy for generalized anxiety disorder. Behaviour

Research and Therapy, 50(2), 100–109.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2011.12.005

Voitsidis, P., Nikopoulou, V. A.,

Holeva, V., Parlapani, E., Sereslis, K., Tsipropoulou, V., Karamouzi, P.,

Giazkoulidou, A., Tsopaneli, N., & Diakogiannis, I. (2021). The mediating

role of fear of COVID-19 in the relationship between intolerance of uncertainty

and depression. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice,

94(3), 884–893. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12315