http://dx.doi.org/10.24016/2022.v8.289

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Academic self-efficacy as a protective factor for the

mental health of university students during the COVID-19 pandemic

La autoeficacia académica como factor

protector de la salud mental en estudiantes universitarios durante la pandemia

de COVID-19

Nayeli Lucía Ampuero-Tello 1, Angel Christopher Zegarra-López 1,2 *, Dharma

Ariana Padilla-López 1, Dafne Silvana Venturo-Pimentel 1

1 Círculo de

Investigación en Psicología, Facultad de Psicología, Universidad de Lima, Lima,

Peru.

2 Grupo de

Investigación en Psicología, Bienestar y Sociedad, Instituto de Investigación

Científica, Universidad de Lima, Lima, Peru.

* Correspondence: Facultad de Psicología, Universidad de Lima. 4600

Avenue Javier Prado Este, Santiago de Surco, Lima, 15023, Peru.

E-mail: azegarra@ulima.edu.pe.

Received: September 05,

2022. | Revised: November 01,

2022. | Accepted: December 08,

2022. | Published Online: December 28,

2022.

Ampuero-Tello, N., Zegarra-López, A., Padilla-López,

D., & Venturo-Pimentel, D. (2022). Academic

self-efficacy as a protective factor for the mental health of university

students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Interacciones, 8,

e289. http://dx.doi.org/10.24016/2022.v8.289

ABSTRACT

Background: University students are vulnerable to developing mental health problems

due to constant exposure to academic demands. A situation that has been

exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic and observed in several recent studies.

Therefore, current practices require further research and identification of

potentially protective factors for mental health. Objective: This study aimed

to analyze academic self-efficacy as a protective factor against depression,

anxiety, and stress in university students. Methods: A cross-sectional

design was used with 3525 university students from Lima, Peru. The prevalence

of depression, anxiety, and stress was measured using the DASS-21. Academic

self-efficacy was measured with the EPAESA and defined as a predictor of the

three mental health conditions. Structural equation modeling was used to test

the model, together with a multigroup analysis for gender and working status. Results: One-third of the

sample had severe to extremely severe symptoms of depression, anxiety, and

stress. Academic self-efficacy was a moderately statistically significant

predictor of the three mental health conditions. Relationships were invariant

to gender and working status.

Conclusions: Self-efficacy can be

considered a protective factor for mental health. Interventions to promote

academic self-efficacy may be effective in reducing depression, anxiety, and

stress in university students. The findings are discussed together with current

studies on the topic.

Keywords: Self Efficacy, Mental health, Depression, Anxiety, Stress, Higher

Education, University Students, COVID-19.

RESUMEN

Antecedentes: los

estudiantes universitarios son propensos a desarrollar problemas de salud

mental debido a la exposición constante a las exigencias académicas. Una

situación que se ha agravado con la pandemia de COVID-19 y se ha observado en

varios estudios contemporáneos. Por esta razón, las prácticas actuales

requieren más investigación e identificación de posibles factores protectores

de la salud mental. Objetivo: El

objetivo de este estudio fue analizar la autoeficacia académica como factor

protector frente a la depresión, la ansiedad y el estrés en estudiantes

universitarios. Método: Se realizó

un diseño transversal en 3525 estudiantes universitarios de Lima, Perú. La

prevalencia de depresión, ansiedad y estrés se midió con el DASS-21. La

autoeficacia académica se midió con la escala EAPESA y se definió como

predictor de las tres condiciones de salud mental. Se llevó a cabo un enfoque

de modelado de ecuaciones estructurales para probar el modelo junto con un

análisis multigrupo con respecto al sexo y la situación laboral. Resultados: Un tercio de la muestra

presentó síntomas severos a extremadamente severos de depresión, ansiedad y

estrés. La autoeficacia académica fue un predictor estadísticamente

significativo moderado de las tres condiciones de salud mental. Las relaciones

fueron invariantes en cuanto al sexo y la situación laboral. Conclusiones: La autoeficacia puede

considerarse como un factor protector de la salud mental. Las intervenciones

para fomentar la autoeficacia académica podrían ser efectivas para reducir la

depresión, la ansiedad y el estrés en estudiantes universitarios. Los hallazgos

se discuten junto con los estudios contemporáneos sobre el tema.

Palabras clave: Autoeficacia, Salud mental, Depresión, Ansiedad,

Estrés, Educación Superior, Estudiantes Universitarios, COVID-19.

BACKGROUND

The COVID-19 pandemic posed an unprecedented challenge

to governments around the world due to its alarming contagiousness and severity

of symptoms (Krishnan et al., 2021). Since the World Health Organization (WHO)

declared it a pandemic on March 11, 2020, most countries have opted to

implement lockdown and social distancing measures to contain its spread. As a

result, organizations that are not essential to governments, such as

educational institutions, have been forced to adapt from a face-to-face to a

remote methodology. Preparing for distance learning requires addressing several

immediate challenges related to access to digital connectivity and adapting

pedagogical teaching strategies to a virtual context to ensure appropriate

learning (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

[UNESCO], 2020). Nevertheless, various economic, social, and health factors

have affected the academic performance of university students during the

pandemic (Aucejo et al., 2020; Reyes-Portillo et al.,

2022). Among these, students' mental health was one of the most affected

factors, consistently reported in several studies (e.g., Chen & Lucock, 2022; Elharake et al.,

2022).

According to the World Health Organization (WHO,

2022), mental health is essential to the overall well-being of a person. In

this sense, mental health problems are considered the leading cause of

disability and a fundamental public health problem worldwide. During the

COVID-19 pandemic, a greater emphasis was placed on the mental health of

vulnerable socio-demographic groups, such as university students (Son et al.,

2020). For most universities, social restrictions imposed strict social

learning measures, which became a constant stressor for students as it required

greater effort to adapt to a new learning approach and to cope with

pandemic-related stressors (Ghazawy et al., 2021).

Indeed, previous research has already shown that university students tend to

experience stress, anxiety, and depression due to the stressful nature of

academic demands (Limone & Toto, 2022).

Indeed, adolescents and young adults are vulnerable to

mental health problems (Nobre et al., 2021), such as

depression, anxiety, and stress are common in this socio-demographic group (Das

et al., 2016; García-Carrión et al., 2019; Silva et

al., 2020). Also, mental disorders affect motivation, concentration, and social

interactions, which are relevant aspects of the academic performance of

university students (Son et al., 2020). Furthermore, mental disorders rank high

among the factors that hinder academic success (Agnafors

et al., 2021). Globally, between 12 and 50% of university students meet at

least one diagnostic criterion for one or more mental disorders (Bruffaerts et al., 2018). However, recent studies have

shown an increase in mental health conditions due to the COVID-19 pandemic and

social distancing measures (e.g., Xiong et al., 2020;

Tsamakis et al., 2021; Jones et al., 2021; Chadi et

al., 2022).

In Peru, university students usually belong to

adolescence and early adulthood, being between 15 and 29 years old. The

Peruvian Ministry of Health (MINSA, 2020) estimates that 20% of the adult

population has mental health problems, highlighting stress, depression, and

anxiety. Ruiz-Frutos et al. (2021) found that

approximately 59% of Peruvian adults suffered from high levels of psychological

distress during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, Antiporta et al. (2021) showed that the pandemic had a

drastic effect on the general mental health of the Peruvian population, with

three out of ten participants reporting moderate to severe symptoms of

depression. Notably, the prevalence of these symptoms was five times higher

than the national level reached in 2018. In addition, Figueroa-Quiñones et al (2022) conducted a study on university

students during the pandemic and showed that 75% of students had mild to severe

symptoms of depression, as well as multiple difficulties in performing daily

activities, pain, and general discomfort, which significantly affected their

quality of life.

In the context of the increasing prevalence of mental

health problems, studies are needed to identify potential protective factors

against these problems in university students. This study aimed to assess

academic self-efficacy as a potential protective factor. Self-efficacy, a

concept proposed by Albert Bandura, refers to an individual's assessment of

their abilities and capabilities to perform tasks of varying difficulty levels.

Self-efficacy emphasizes an individual's past performance (Bong & Clark,

1999). Along with goal setting, self-efficacy is one of the most relevant

motivational predictors of how well people will perform in almost any activity.

This means that self-efficacy is a powerful determinant of people's effort,

persistence, strategy, training, and job performance (Heslin

et al., 2017). In academic contexts, self-efficacy is defined as an

individual's belief that they will be able to perform assigned academic tasks

at a given level. Several studies on academic self-efficacy have found that it

is directly related to perceived academic performance, stress, general

satisfaction, school attendance, school adjustment, and problem-coping behavior

(Karakose et al., 20-23).

In the academic context, it is necessary to consider

self-efficacy, as students with high self-efficacy set more complex goals and

show high commitment to achieving them. In addition, positive self-efficacy is

a predictor of good academic performance (Yokoyama, 2019). Furthermore,

self-efficacy has a strong correlation with mental health, which has been

demonstrated in the results of different studies (e.g., Grøtan

et al., 2019; García-Álvarez et al., 2021). For example, Tak

et al. (2017) shows that there is a negative relationship between academic

self-efficacy and depressive symptoms in early to middle adolescence. This

finding is echoed by Tahmassian and Jalali Moghadam (2011), who also found a negative

relationship between academic self-efficacy and anxiety. Furthermore, Sabouripour et al. (2021) state that self-efficacy is

crucial for stress management as it influences the evaluation of stressors and

allows the correct implementation of methods to deal with them. In this sense,

effective coping strategies to deal with stressors are associated with higher

student self-efficacy (Freire et al., 2020).

As mentioned above, symptoms of

depression, anxiety, and stress are considered important indicators of mental

health that can negatively affect well-being (Wainberg

et al., 2017). This study focused on one protective factor within the academic

context, academic self-efficacy, as a potentially protective factor against the

three aforementioned mental health conditions during the first year of the

COVID-19 pandemic. As shown in the literature, the pandemic itself brought

several stressors, and for university students, most of them are related to

changes in their academic efforts and well-being (e.g., Oliveira Carvalho et

al., 2021; Sauer et al., 2022; Werner et al., 2021). For this reason, we

hypothesize that higher academic self-efficacy in university students will be

associated with less severe symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress.

Therefore, this study aimed to determine the predictive role of academic

self-efficacy on depression, anxiety, and stress in university students

residing in Lima Metropolitana, Peru, during the

first year of the COVID-19 pandemic.

METHOD

Participants

A sample of 3525 undergraduate university students

from Lima, Peru was recruited. Inclusion criteria included participants who

were at least 18 years old and enrolled in correspondence courses during the

2020 academic year. Data were collected through an online survey that indicated

the voluntary nature of participation and informed consent, which had to be

accepted before answering further questions. The sample consists of 32.40%

males and 67.60% females, aged between 18 and 28 years (M=20.52, SD=2.00). In

addition, 20.79% of the sample reported that they were working or in pre-professional

work placements alongside their respective studies, and the remaining 79.21%

were studying full-time.

Instruments

Academic Self-Efficacy

Academic self-efficacy is defined as students' own

beliefs about their ability to organize and perform actions related to the

achievement of academic goals (Bandura, 2001). In the present study, this

variable is operationalized by the Specific Perceived Self-Efficacy Scale for

Academic Situations (EAPESA; Palenzuela, 1983). The

original version consists of 10 items. However, it was decided to use a 9-item

version resulting from the adaptation study of the scale in Peruvian university

students. The format corresponds to Likert-type items with four response

alternatives, from never to always. In terms of its psychometric properties, a

high internal consistency indicates a high reliability (ω=.933) and an excellent fit to a unidimensional model

that reports validity based on its internal structure.

Mental Health

Mental health is measured as symptoms of depression,

anxiety, and stress experienced by university students and is operationalized

in the Spanish versions of the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scales (DASS). Lovinbond and Lovinbond (1995)

proposed the original 42-item scale; however, Antony et al. (1998) showed that

a shortened 21-item version retained fair to excellent psychometric properties

and the ability to discriminate features of depression, stress, and anxiety as

well as the full version. Both versions have been renamed DASS-42 and DASS-21

respectively. In the present study, the Spanish version of the DASS-21 is used,

where the items are presented with a four-level response scale from “Did not apply to me at all” to “Applied to me very much or most of the time”.

The total scores of the DASS-21 can be used to categorize people into symptom

severity levels: None, Mild, Moderate, Severe, and Extremely severe. In terms of its

psychometric properties, high internal consistency was found for the three

subscales (ω=.848-.932), indicating strong evidence of

reliability. In addition, an excellent fit to a multidimensional correlated

3-factor model provided evidence of validity based on its internal structure.

Data Analysis

Procedures

The data analysis is based on a structural equation

modeling (SEM) approach, an analytical technique that integrates the modeling

of latent variables through the fitting of measurement models and the analysis

of their relationships through structural models (Wang & Wang, 2020). In

this way, SEM uses the matrix of covariances or correlations of the observed

data for the joint estimation of the parameters of a model and the evaluation

of its respective fit, without having to rely on the estimation of overall

scores that ignore the theoretical models proposed for the latent variables (McNeish & Wolf, 2020), although this may be useful in

certain circumstances (Widaman & Revelle, 2022).

First, an exploratory analysis is presented together

with the distribution of severity of depression, anxiety, and stress as an

approximation of the prevalence of these mental health conditions in the

observed sample. Subsequently, the measurement models for the EAPESA and

DASS-21 are tested using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA; Brown, 2015),

together with the estimation of reliability measures with the omega coefficient

when assuming a congeneric model (Cho, 2016).

The structural models are then evaluated against the

main conceptual hypothesis of the study. The evaluation of the models is

developed considering the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Root Mean Squared Error

of Approximation (RMSEA), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR)

indicators. Values of CFI≥.95, RMSEA≤.05, and SRMR≤.06 are established as

indicators of excellent fit, while CFI≥.90, RMSEA≤.08, and SRMR≤.08 suggest an

adequate value (Keith, 2019). The analyses are developed taking into account

polychoric correlation matrices, consistent with the ordinal nature of the

variables. The WLSMV estimator will be used in congruence with the use of

polychoric matrices and is robust to deviations from normality (Li, 2016).

To end with, a multigroup analysis is carried out to

assess the invariance of the proposed relationships regarding sex and work

status. We follow the modern approach shown by Svetina

et al. (2020) which is an applied demonstration of Wu and Estabrook (2016)

approach to assess measurement invariance for ordered categorical outcomes in

which a baseline model is established, followed by subsequent models where the

thresholds and loadings are constrained. Then, we analyzed the structural

invariance by constraining the latent variable variances, covariances, and

regressions. Incremental indexes ΔCFI, ΔRMSEA, and ΔSRMR were used to determine

invariance following common suggestions by Chen (2007), Rutkowski and Svetina

(2014;2017), and Svetina and Rutkowski (2017).

Ethical

considerations

The participants completed an online questionnaire

after expressing their informed consent. The research project was accepted by

the Comité de Investigación

y Ética (CIE) of the Faculty of Psychology of the

Universidad de Lima.

RESULTS

Prevalence of

Depression, Anxiety and Stress and Exploratory Analysis

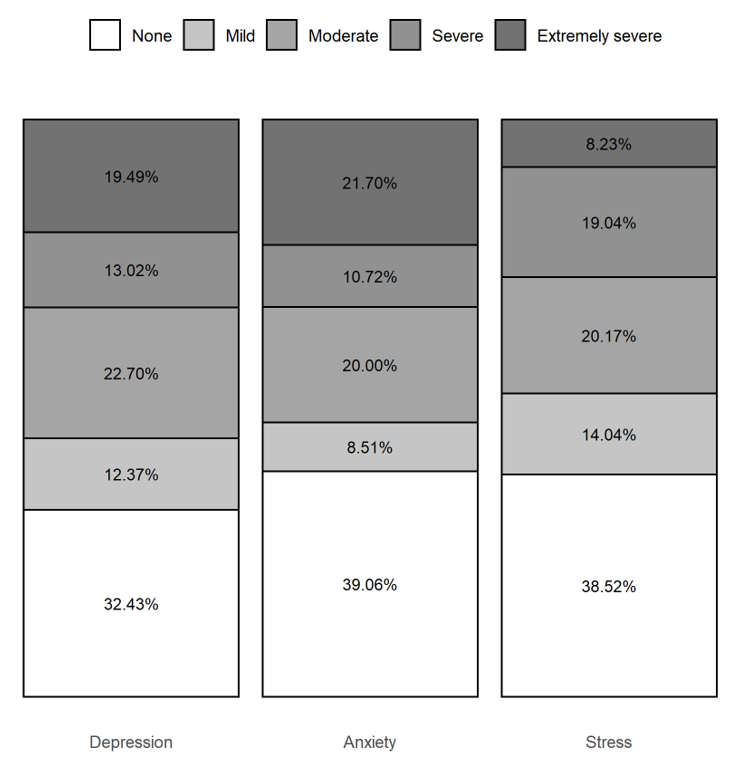

An approximation of the prevalence of the severity of

depression, anxiety, and stress in the sample of university students is

presented in Figure 1. As can be seen, the distribution of severity in the

three mental health conditions explored denotes that approximately one-third of

the sample experienced severe to extremely severe symptoms of all three

conditions. In the same way, most participants presented a degree of severity

that is mild at best. The similarities in the observed distributions represent

empirical evidence about the relationship between the mental health conditions

studied, which means that correct modeling of these variables must recognize

their respective relationship.

Figure 1. Prevalence of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress in University

Students.

A set of descriptive statistics on the total scores is

presented in Table 1, as an exploratory analysis of the distribution of the

observed measures. Additionally, no atypical response patterns were identified

in the data set; however, floor effects were identified for the three mental

health measures and a ceiling effect was identified for the academic

self-efficacy measure. The presence of both indicators supposes limitations

that were addressed by using robust estimation methods towards non-normality.

Table 1. Descriptive

Statistics of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Total Scores

|

Variable |

M |

SD |

Med |

γ₁ |

γ₂ |

|

Depression |

16.178 |

11.315 |

14 |

0.465 |

-0.724 |

|

Anxiety |

11.956 |

9.741 |

10 |

0.902 |

0.203 |

|

Stress |

18.615 |

9.956 |

18 |

0.199 |

-0.624 |

|

Academic

Self-Efficacy |

24.069 |

5.923 |

24 |

0.037 |

-0.500 |

Note. M = Mean, SD = Standard Deviation, Med = Median, γ₁ = Skewness, γ₂ = Kurtosis.

Measurement

Models

The one-dimensional measurement model proposed for the

EAPESA scale showed an excellent fit to the empirical data X2(27)=743.010, CFI=.990, RMSEA=.087 (90% CI .081-.092),

SRMR=.026. High factor loadings were found for all 9 items ranging from λ=0.732

to λ=0.883. These measures denoted a high observed internal consistency ω=.933 and average explained variance AVE=0.683. In the

same way, the multidimensional 3-factor model proposed for the DASS-21 scale

presents an appropriate fit to the empirical data X2(186)=6042.479,

CFI=.936, RMSEA=.095 (90% CI .092-.097), SRMR=.054, with high factor loadings,

internal consistency, and average explained variance for depression λ=.650-.882,

ω=.921, AVE=.672 ; anxiety λ=.474-.871, ω=.848, AVE=.524; and stress

λ=.681-.847, ω=.932, AVE=.561.

Structural

Model

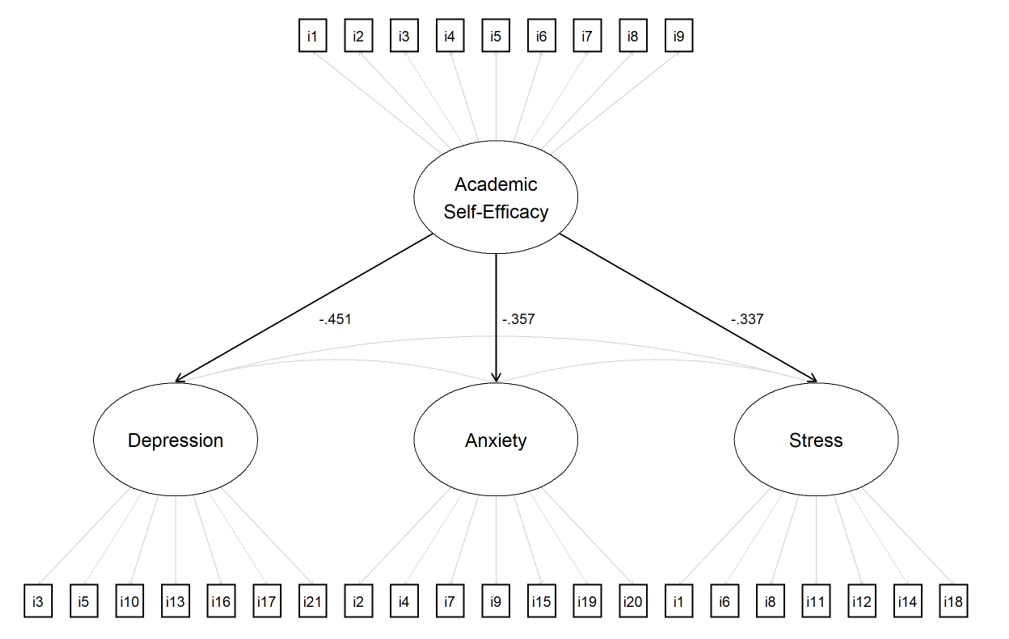

The identified relationships supported the suitability

of the proposed model. Figure 2 presents the theoretical model proposed in this

study, with the respective estimated parameters. In summary, the estimated

model presents an excellent fit to the data X2(399)=5700.779,

CFI=.959, RMSEA=.061 (90% CI .060-.063), SRMR=.046. A moderate effect size was

found in the negative statistically significant relationship between perceived

academic self-efficacy and depression β=-.451, p<.001; anxiety β=-.357, p<.001; and stress β=-.337, p<. 001. Since the initial proposed model

showed an excellent fit to the empirical data, no ex post facto modifications

were made.

Figure 2. Proposed Structural Model for the Relationship Between

Academic Self-Efficacy on Depression, Anxiety and Stress.

Multigroup

Models

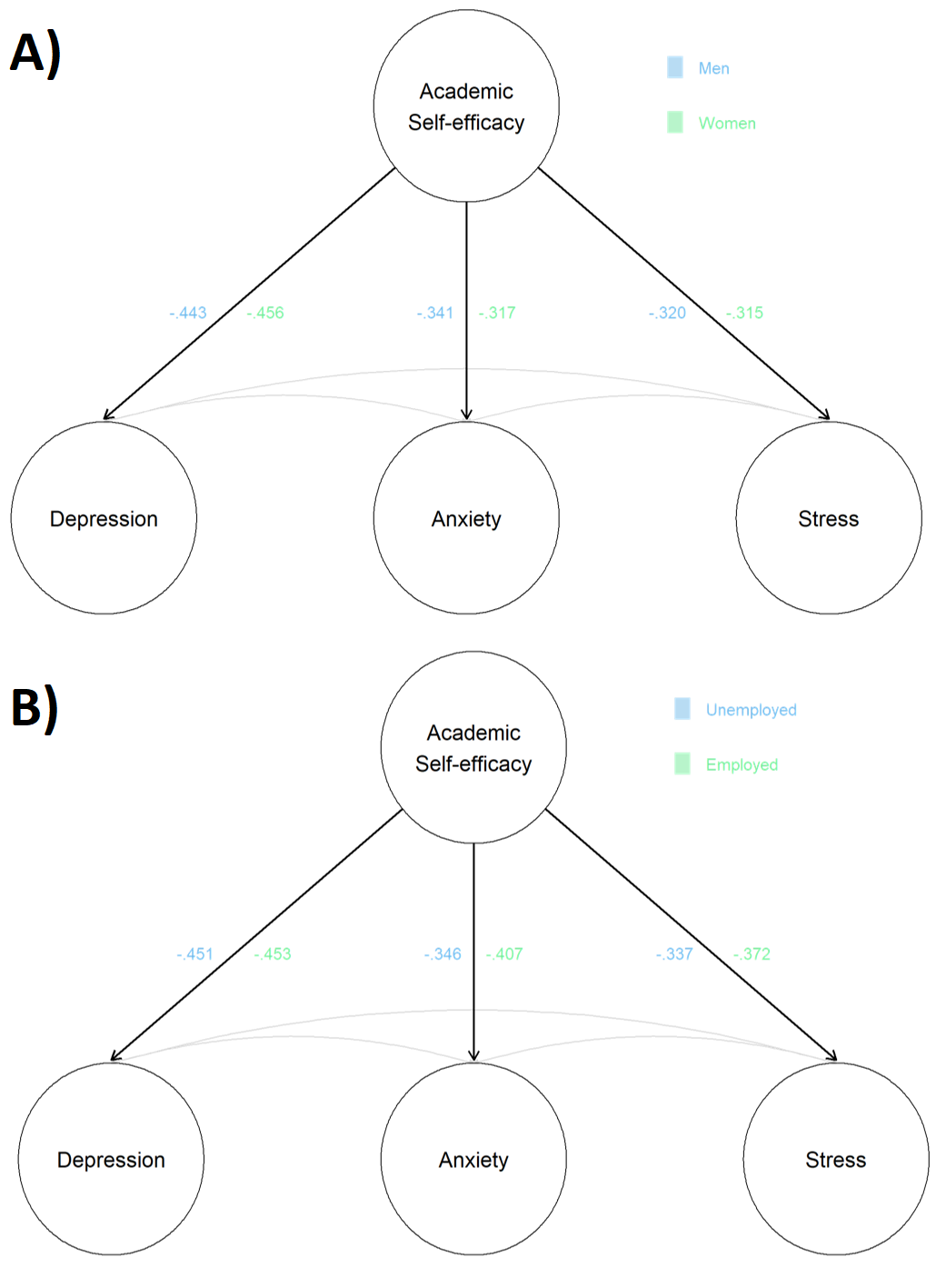

To further test the proposed model, a multigroup

analysis was carried out and its results are shown in Table 2. We found

supporting evidence for thresholds and loadings invariances regarding sex and

work status which denotes evidence for measurement invariance. Additionally,

structural invariance was supported for both sex and work status groups,

denoting invariant latent variable variances and covariances, as well as the

proposed regression paths on the structural model. As a reference, the

parameters estimated in the configural models are shown in Figure 3 to show no

practical differences regarding both sex and work status.

Table 2. Multigroup Analysis Regarding Sex and Work

Status.

|

Model |

χ² (df) |

CFI |

∆CFI |

RMSEA (CI 90%) |

∆RMSEA |

SRMR |

∆SRMR |

|

|

Sex |

Baseline |

5902.396 (798) |

.959 |

- |

.060 (.059, .062) |

- |

.048 |

- |

|

Thresholds invariance |

6179.408 (854) |

.957 |

-.002 |

.059 (.058, .061) |

-.001 |

.048 |

.000 |

|

|

Thresholds and loadings invariance |

6110.116 (880) |

.958 |

.001 |

.058 (.057, .059) |

-.001 |

.048 |

.000 |

|

|

Structural invariance |

4196.830 (890) |

.974 |

.024 |

.046 (.045, .047) |

-.012 |

.048 |

.000 |

|

|

Work status |

Baseline |

5785.346 (798) |

.960 |

- |

.060 (,058, 061) |

- |

0.047 |

- |

|

Thresholds invariance |

5933.104 (854) |

.959 |

-.001 |

.058 (.057, .060) |

-.002 |

0.047 |

.000 |

|

|

Thresholds and loadings invariance |

5892.764 (880) |

.959 |

.000 |

.057 (.055, .058) |

-.001 |

0.047 |

.000 |

|

|

Structural invariance |

3977.289 (890) |

.975 |

.024 |

.044 (.043, .046) |

-.013 |

0.048 |

.001 |

Note:

χ² = Chi-squared

value, df = degrees of freedom, CFI = Comparative Fit

Index, RMSEA = Root Mean Square Error of Approximation, CI = Confidence

intervals. SRMR = Standardized Root Mean Square Residual. ∆CFI = Change in CFI.

∆RMSEA = Change in RMSEA. ∆SRMR = Change in SRMR.

Figure 3. Estimated Parameters on the Configural Models

Regarding Sex and Work Status.

DISCUSSION

Most university students face multiple challenges in

the transition towards accessing higher education such as the need to adapt to

academic demands in a highly competitive environment while still learning to

make independent decisions about their lives and careers (Bruffaerts

et al., 2018; Hernández-Torrano et al., 2020). These

challenges impose psychological distress in a way that the probability of

suffering from mental health problems such as anxiety and depression can be six

times higher for graduate students than for the general population (Evans et

al., 2018). For this reason, there is a growing need to strengthen policies to

address mental health problems on university students, as well as increasing

the studies to further understand the burden of mental health challenges and

potential coping mechanisms (Grando Gaiotto et al., 2021; Nair & Otaki, 2021). In addition,

the COVID-19 pandemic brought a stronger need to address mental health problems

in university students, since several studies show an increase in prevalence of

psychological distress and multiple negative repercussions for this

sociodemographic group (e.g., Antiporta et al., 2021;

Chen & Lucock, 2022). In response to this need,

it is necessary and important to identify protective factors to mental health

problems in university students. Since academic demands are among the most

related factors to psychological distress on university students, the aim of

this study is to propose academic self-efficacy as a potential protective

factor against mental health problems. Self-efficacy is defined as the judgment

that a person has about their own skills and abilities in order to achieve

success in different tasks with different levels of complexity (Bandura, 2001).

In the academic field, self-efficacy allows university students to propose

complex tasks and commit themselves, to a greater extent, to carrying them out.

Academic self-efficacy is significantly related to psychological well-being and

mental health, since several authors have found that a higher confidence to

address academic tasks has a negative relationship with mental health

disorders, such as depression, anxiety, and stress (e.g., Tak

et al., 2017; Tahmassian & Jalali

Moghadam, 2011; Sabouripour et al., 2021; Freire et

al., 2020).

In correspondence to several studies on the prevalence

of mental health problems on university students during the COVID-19 pandemic

(e.g., Chen & Lucock, 2022; Li et al., 2021; Wang

et al., 2021; Chang et al., 2021), we found that approximately one third of the

sample experienced severe to extremely severe symptoms of depression, anxiety,

and stress. In most cases, students faced a disruption on their lives during

the pandemic such as the feelings of loneliness due to the social isolation

practices, lack of financial resources which increased stress and implied poor

nutrition and housing, as well as the need to keep adapting to academic demands

(Sauer et al., 2022). As such evidence persists, researchers conclude that

there is a strong need for providing mental health care resources to university

students, not only by their educational institution (Copeland et al., 2021),

but also as a government policy (Chen et al., 2020).

Regarding academic self-efficacy as a potential

protective factor, we observed a statistically significant negative

relationship with depression, with a moderate effect size. As noted, our

results are consistent with previous findings on the literature (e.g., Tak et al., 2017). García-Méndez and Rivera (2020) argued

that a severe experience of depressive symptoms implies a constant negative

perspective on current and future events as well as a lack of confidence in

one’s own abilities. On the contrary, a higher academic self-efficacy allows

university students to be aware and have confidence in their own abilities and

skills in different academic tasks. In this way, a positive self-perspective

towards reaching academic goals may prevent a pessimistic thinking about future

academic endeavors and even allowing students to see academic challenges as

opportunities to develop instead of potential stressors (Chen et al., 2020; Krifa et al., 2022).

With respect to anxiety, our results denote a moderate

statistically significant relationship with academic self-efficacy. Previous

studies have consistently found that a strong believe in one’s capability to

achieve academic goals is related to a lesser experience of anxiety-related

symptoms on undergraduate students (Tahmassian & Jalali, 2011; Faramarzi & Khafri, 2017; Hood et al., 2020). To further understand

this relationship, it is important to note that anxiety is characterized by the

persistent presence of worried thoughts and concerns either internal or

external that often provoke the avoidance of certain situations as well as the

experience of physical symptoms such as dizziness, trembling, increased heart

rate, among others (Craske et al., 2017). In this

sense, having a strong sense of credibility on one’s abilities reduces

uncertainty and concerns regarding academic chores while also reducing potential

avoidance behaviors such as absences or dropout. As Bandura (2007) stated,

persons believing in one’s ability to control potential treats are not

perturbed by them; in contrast, a low self-efficacy will experience high levels

of anxiety.

With reference to stress, a statistically significant

negative relationship was identified with academic self-efficacy, with a

moderate effect size. This finding is consistent with several investigations

that address the strong relationship between self-efficacy and positive

adaptation to stressful situations (Cattelino et al.,

2021; Freire et al., 2020). In fact, if a student has better strategies for

coping with stress, they will be able to feel more confident about their own

capabilities, thus they will achieve their academic goals; however, if a

student does not have efficient coping strategies towards stress, their

academic self-efficacy would be affected in such a way that the student would

not be able to successfully complete their assignments because they will not

feel capable of doing them and will experience chores as potential stressors

(Mete, 2021). In addition, Sabouripour et al. (2021)

denote that self-efficacy is important to effectively manage stress since one’s

beliefs on their own capabilities influence the way in which they assess

potential stressors and, in an academic environment, such assessment would lead

to a more efficient assignment of coping strategies do deal with academic

stressors (Freire et al., 2020). Furthermore, Meyer et al. (2022) explains that

self-efficacy can act as a mediator between a person’s beliefs regarding

COVID-19 and the potential stressful effects of the pandemic, suggesting that

fostering self-efficacy can lead to reducing the impact of stressing factors.

Further multigroup analyses revealed that the proposed

relationships were invariant among two main demographic groups. The invariance

of regression coefficients between men and women suggests that the strength of

the relationship is the same for both groups. This is particularly revealing

since it has been shown in previous studies that women tend to experience more

severe mental health problems during the pandemic (Dal Santo et al., 2022). The

same result has been found for work status, even though working and studying impose

higher demands on higher education students which is related to more mental

health problems and considerations (Pedrelli et al.,

2015).

In conclusion, academic self-efficacy can act as a

protective factor towards mental health problems related to depression,

anxiety, and stress. The observed relationship between academic self-efficacy

and all three mental health conditions was statistically significant, moderate,

and negative, with a slightly higher effect size for depression. Regarding

depression, a higher academic self-efficacy allows university students to be

more confident in their own skills, thus allowing them to successfully address

academic tasks and avoid negative feelings about their present and future

academic endeavors. With reference to anxiety, higher academic self-efficacy

prevents worried thoughts and concerns regarding academic chores; as a

consequence, academic demands are not seen as potential threats and students

are not perturbed by them. Lastly, having a strong confidence in one’s own

abilities can act as a coping mechanism towards stressful academic situations.

Lastly, multigroup analyses revealed that the measurement and structural model

are invariant across sex and work status. Thus, we recommend improving efforts

to foster academic self-efficacy on university students in order to reduce the

mental health impact that the academic environment and the COVID-19 pandemic

brought.

It is important to note that this study presents some

limitations. To begin with, we did not use a randomized sampling procedure

which limits the generalizability of results to wider populations. This is

because the non-probabilistic sampling doesn't give each individual the

possibility of being part of the sample, which is why it may not be

representative of the population. Furthermore, we employed a cross-sectional

approach and longitudinal designs may bring further insights into the dynamics

of the proposed relationships.

ORCID

Nayeli Lucía Ampuero Tello https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5672-5682

Angel Christopher Zegarra López https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5873-745X

Dharma Ariana Padilla López

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3410-2761

Dafne Silvana Venturo

Pimentel https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8106-4182

CONTRIBUTION

OF THE AUTHORS

Nayeli Lucía Ampuero Tello: Design of the study, literature search,

drafting of the manuscript, and final revision of the manuscript.

Angel Christopher Zegarra

López: Design of the study, statistical procedures and analysis, drafting of

the manuscript, translation to English, and final revision of the manuscript.

Dharma Ariana Padilla

López: Design of the study, literature search, drafting of the manuscript, and

final revision of the manuscript.

Dafne Silvana Venturo Pimentel: Design of the study, literature search,

drafting of the manuscript, and final revision of the manuscript.

FUNDING

Our study was

self-financed.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors of

this study report no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Not applicable.

REVIEW

PROCESS

This study has

been reviewed by external peers in a double-blind mode. The editor in charge Anthony Copez-Lonzoy. The review process can be

found as supplementary material 1.

DATA

AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The datasets that support the present study are

available upon reasonable request and with permission of the Faculty of

Psychology and the Research and Ethics Committee of the Universidad de Lima.

DISCLAIMER

The authors are responsible for all

statements made in this article.

REFERENCES

Agnafors, S., Barmark, M., & Sydsjö, G. (2021). Mental health and academic performance:

A study on selection and causation effects from childhood to early adulthood. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric

Epidemiology, 56(5), 857–866. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01934-5

Antiporta, D., Cutipé, Y., Mendoza,

M., Celentano, D., Stuart, E., & Bruni, A. (2021). Depressive symptoms

among Peruvian adult residents amidst a National Lockdown during the COVID-19

pandemic. BMC psychiatry, 21(111),

1-12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03107-3

Antony, M. M., Bieling, P.

J., Cox, B. J., Enns, M. W., & Swinson, R. P. (1998). Psychometric

properties of the 42-item and 21-item versions of the Depression Anxiety Stress

Scales in clinical groups and a community sample. Psychological Assessment, 10(2), 176–181.

https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.10.2.176

Aucejo, E. M., French, J., Ugalde Araya, M. P., & Zafar, B. (2020). The

impact of COVID-19 on student experiences and expectations: Evidence from a

survey. Journal of Public Economics, 191,

104271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104271

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An

agentic perspective. Annual Review of

Psychology, 52(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1

Bandura, A. (1988). Self-efficacy conception of

anxiety. Anxiety Research, 1(2),

77–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615808808248222

Bong, M., & Clark, R. (1999). Comparison between

self-concept and self-efficacy in academic motivation research. Educational

Psychologist, 34(3), 139-153. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep3403_1

Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research (2nd ed.). The

Guilford Press.

Bruffaerts, R., Mortier, P., Kiekens,

G., Auerbach, R., Cuijpers, P., Demyttenaere,

K., Green, J., Nock, M., & Kessler, R. (2018). Mental health problems in

college freshmen: Prevalence and academic functioning. Journal of Affective Disorders, 225(1), 97-103.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.07.044

Cattelino, E., Testa, S., Calandri, E.,

Fedi, A., Gattino, S.,

Graziano, F., Rollero, C., & Begotti,

T. (2021). Self-efficacy, subjective well-being and positive coping in

adolescents with regard to COVID-19 lockdown. Current Psychology, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01965-4

Chadi, N., Ryan,

N. C., & Geoffroy, M. C. (2022). COVID-19 and the impacts on youth mental

health: Emerging evidence from longitudinal studies. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 113(1), 44–52.

https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-021-00567-8

Chang, J. J., Ji,

Y., Li, Y. H., Pan, H. F., & Su, P. Y. (2021).

Prevalence of anxiety symptom and depressive symptom among college students

during COVID-19 pandemic: A meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 292, 242–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.05.109

Chen, B., Sun,

J., & Feng, Y. (2020). How have COVID-19 isolation policies affected young

people's mental health? - Evidence from Chinese college students. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1529. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01529

Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit

indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural

Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(3), 464–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701301834

Chen, T., & Lucock, M.

(2022). The mental health of university students during the COVID-19 pandemic:

An online survey in the UK. PloS One, 17(1), e0262562.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0262562

Cho, E.

(2016). Making reliability reliable: A systematic

approach to reliability coefficients. Organizational

Research Methods, 19(4), 651-682. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428116656239

Copeland, W. E., McGinnis, E., Bai, Y., Adams, Z.,

Nardone, H., Devadanam, V., Rettew,

J., & Hudziak, J. J. (2021). Impact of COVID-19

pandemic on college student mental health and wellness. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 60(1),

134–141.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2020.08.466

Craske, M. G., Stein, M. B., Eley, T. C., Milad, M.

R., Holmes, A., Rapee, R. M., & Wittchen, H. U. (2017). Anxiety disorders. Nature Reviews. Disease Primers, 3,

17024. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2017.24

Dal Santo, T., Sun, Y., Wu, Y., He, C., Wang, Y.,

Jiang, X., Li, K., Bonardi, O., Krishnan, A., Boruff, J. T., Rice, D. B., Markham, S., Levis, B., Azar, M., Neupane, D., Tasleem,

A., Yao, A., Thombs-Vite, I., Agic,

B., Fahim, C., … Thombs, B. D. (2022). Systematic review of mental health

symptom changes by sex or gender in early-COVID-19 compared to pre-pandemic. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 11417.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-14746-1

Das, J. K., Salam, R. A., Lassi, Z. S., Khan, M. N.,

Mahmood, W., Patel, V., & Bhutta, Z. A. (2016).

Interventions for adolescent mental health: An overview of systematic reviews. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 59(4S),

S49–S60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.020

Elharake, J. A., Akbar, F., Malik, A. A., Gilliam, W., &

Omer, S. B. (2022). Mental health impact of COVID-19 among children and college

students: A systematic review. Child

Psychiatry and Human Development, 1–13. Advance online publication.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-021-01297-1

Evans, T. M., Bira, L., Gastelum,

J. B., Weiss, L. T., & Vanderford, N. L. (2018).

Evidence for a mental health crisis in graduate education. Nature Biotechnology, 36(3), 282–284.

https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.4089

Faramarzi, M., & Khafri, S.

(2017). Role of alexithymia, anxiety, and depression in predicting

self-efficacy in academic students. TheScientificWorldJournal, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/5798372

Figueroa-Quiñones,

J., Cjuno, J., Machay-Pak, D., & Ipanaqué-Zapata,

M. (2022). Quality of life and depressive symptoms

among Peruvian university students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 781561.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.781561

Freire, C., Ferradás, M., Regueiro, B., Rodríguez, S., Valle, A., & Núñez, J. C. (2020). Coping strategies and self-efficacy in

university students: A person-centered approach. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 841. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00841

Gaiotto, E., Trapé, C. A., Campos,

C., Fujimori, E., Carrer, F., Nichiata,

L., Cordeiro, L., Bortoli, M. C., Yonekura,

T., Toma, T. S., & Soares, C. B. (2022). Response to college students'

mental health needs: A rapid review. Revista de Saude Publica, 55, 114.

https://doi.org/10.11606/s1518-8787.2021055003363

García-Álvarez,

D., Hernández-Lalinde, J., & Cobo-Rendón, R. (2021).

Emotional intelligence and academic

self-efficacy in relation to the psychological well-being of university

students during COVID-19 in Venezuela. Frontiers

in Psychology, 12, 759701.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.759701

García-Carrión, R., Villarejo-Carballido, B., & Villardón-Gallego,

L. (2019). Children and adolescents mental health: A systematic review of

interaction-based interventions in schools and communities. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 918.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00918

García-Méndez, R. & Rivera, A. (2020). Autoeficacia en la vida académica y rasgos

psicopatológicos. Revista Argentina de

Ciencias del Comportamiento, 12(3), 41-58. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=7846795

Ghazawy, E., Ewis, A., Mahfouz, E.,

Khalil, D., Arafa, A., Mohammed, Z., Mohammed, E., Hassan, E., Abdel, S., Ewis, S., & Mohammed, A. (2021). Psychological impacts

of COVID-19 pandemic on the university students in Egypt. Health Promotion International, 36(4), 1116–1125. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daaa147

Grøtan, K., Sund, E. R., & Bjerkeset,

O. (2019). Mental health, academic self-efficacy and study progress among

college students - The SHoT study, Norway. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 45.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00045

Hernández-Torrano, D., Ibrayeva, L., Sparks, J., Lim, N., Clementi, A., Almukhambetova, A., Nurtayev, Y.,

& Muratkyzy, A. (2020). Mental health and

well-being of university students: A bibliometric mapping of the literature. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1226.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01226

Heslin, P. A., Klehe, U., & Keating, L. A.

(2017). Self-Efficacy. In S. G. Rogelberg (Ed.), The

SAGE Encyclopedia of Industrial and Organizational Psychology (pp.

1401-1406). SAGE

Hood, S., Barrickman, N., Djerdjian, N., Farr, M., Gerrits,

R., Lawford, H., Magner, S., Ott, B., Ross, K., Roychowdury,

H., Page, O., Stowe, S., Jensen, M., & Hull, K. (2020). Some believe, not

all achieve: the role of active learning practices in anxiety and academic

self-efficacy in first-generation college students. Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education, 21(1), 21.1.19. https://doi.org/10.1128/jmbe.v21i1.2075

Jones, E.,

Mitra, A. K., & Bhuiyan, A. R. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 on mental health in adolescents: A

systematic review. International Journal

of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 2470.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052470

Karakose, T., Polat, H., Yirci, R., Tülübaş, T.,

Papadakis, S., Ozdemir, T., & Demirkol,

M. (2023). Assessment of the relationships between prospective mathematics

teachers’ classroom management anxiety, academic self-efficacy beliefs,

academic amotivation and attitudes toward the teaching profession using

Structural Equation Modelling. Mathematics, 11(2), 449.

https://doi.org/10.3390/math11020449

Keith, T. K.

(2019). Multiple regression and beyond:

An introduction to multiple regression and structural equation modeling (3rd

ed.). Routledge.

Krifa, I., van Zyl, L.

E., Braham, A., Ben Nasr, S., & Shankland, R.

(2022). Mental health during COVID-19 pandemic: The role of optimism and

emotional regulation. International

journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1413. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031413

Krishnan, A., Hamilton, J. P., Alqahtani,

S. A., & Woreta, T. A. (2021). COVID-19: An

overview and a clinical update. World

Journal of Clinical Cases, 9(1), 8–23. https://doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i1.8

Li C. H. (2016).

The performance of ML, DWLS, and ULS estimation with robust corrections in

structural equation models with ordinal variables. Psychological Methods, 21(3), 369–387.

https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000093

Li, Y., Wang, A.,

Wu, Y., Han, N., & Huang, H. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the

mental health of college students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 669119. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.669119

Limone, P., & Toto, G. A. (2022). factors that predispose undergraduates

to mental issues: A cumulative literature review for future research

perspectives. Frontiers in Public Health,

10, 831349. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.831349

Lovibond, P. & Lovibond, S. (1995). The structure

of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress

Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U

McNeish, D., & Wolf, M. G. (2020). Thinking twice about

sum scores. Behavior Research Methods, 52(6),

2287–2305. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-020-01398-0

Mete, P. (2021). Structural relationships between

coping strategies, self-efficacy, and fear of losing one’s self-esteem in

science class. International Journal of

Technology in Education and Science, 5(3), 375-393. https://doi.org/10.46328/ijtes.180

Meyer, N., Niemand, T.,

Davila, A., & Kraus, S. (2022). Correction: Biting the bullet: When

self-efficacy mediates the stressful effects of COVID-19 beliefs. PloS One, 17(3),

e0265330. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0265330

Ministerio

de salud. (2020). Plan de salud mental

Perú, 2020 - 2021 (En el contexto COVID-19). http://bvs.minsa.gob.pe/local/MINSA/5092.pdf

Nair, B., & Otaki, F. (2021). Promoting university

students' mental health: A systematic literature review introducing the

4m-model of individual-level interventions. Frontiers

in Public Health, 9, 699030. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.699030

Nobre, J., Oliveira, A., Monteiro, F., Sequeira,

C., & Ferré-Grau, C. (2021). Promotion of Mental

Health Literacy in Adolescents: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(18),

9500. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189500

Oliveira Carvalho, P., Hülsdünker,

T., & Carson, F. (2021). The impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on European

students' negative emotional symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Behavioral Sciences, 12(1), 3.

https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12010003

Palenzuela,

D. (1983). Construcción y validación de una escala de autoeficacia percibida

específica de situaciones académicas. Análisis

y Modificación de Conducta, 9(21), 185-219. https://doi.org/10.33776/amc.v9i21.1649

Pedrelli, P., Nyer, M., Yeung, A., Zulauf, C., & Wilens, T.

(2015). College students: Mental health problems and treatment considerations. Academic Psychiatry: The Journal of the

American Association of Directors of Psychiatric Residency Training and the

Association for Academic Psychiatry, 39(5), 503–511.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-014-0205-9

Reyes-Portillo, J. A., Masia

Warner, C., Kline, E. A., Bixter, M. T., Chu, B. C.,

Miranda, R., Nadeem, E., Nickerson, A., Ortin

Peralta, A., Reigada, L., Rizvi, S. L., Roy, A. K., Shatkin, J., Kalver, E., Rette,

D., Denton, E. G., & Jeglic, E. L. (2022). The

Psychological, academic, and economic impact of COVID-19 on college students in

the epicenter of the pandemic. Emerging Adulthood, 10(2),

473–490. https://doi.org/10.1177/21676968211066657

Ruiz-Frutos,

C., Palomino-Baldeón, J., Ortega-Moreno, M., Villavicencio-Guardia, M., Dias, A., Bernardes, J., & Gómez-Salgado, J. (2021). Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in

Peru: Psychological distress. Healthcare,

9(6), 691. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9060691

Rutkowski, L., & Svetina,

D. (2014). Assessing the hypothesis of measurement invariance in the context of

large-scale international surveys. Educational

and Psychological Measurement, 74(1), 31–57.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164413498257

Rutkowski, L., & Svetina,

D. (2017). Measurement invariance in international surveys: Categorical

indicators & fit measure performance. Applied

Measurement in Education, 30(1), 39–51.

https://doi.org/10.1080/08957347.2016.1243540

Sabouripour, F., Roslan, S., Ghiami, Z., & Memon, M. A. (2021). Mediating role of

self-efficacy in the relationship between optimism, psychological well-being,

and resilience among Iranian students. Frontiers

in Psychology, 12, 675645. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.675645

Sauer, N., Sałek, A., Szlasa, W., Ciecieląg, T., Obara, J., Gaweł, S., Marciniak,

D., & Karłowicz-Bodalska, K. (2022). The impact

of COVID-19 on the mental well-being of college students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(9),

5089. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095089

Silva, S.

A., Silva, S. U., Ronca, D. B., Gonçalves, V., Dutra,

E. S., & Carvalho, K. (2020). Common mental disorders prevalence in adolescents: A systematic review

and meta-analyses. PloS One, 15(4), e0232007.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232007

Son, C., Hegde, S., Smith, A., Wang, X., & Sasangohar, F. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 on college

students' mental health in the United States: Interview survey study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(9).

https://doi.org/10.2196/21279

Svetina, D., & Rutkowski, L. (2017). Multidimensional

measurement invariance in an international context: Fit measure performance

with many groups. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 48(7),

991–1008. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022117717028

Svetina, D., Rutkowski, L., & Rutkowski, D. (2020).

Multiple-group invariance with categorical outcomes using updated guidelines:

An illustration using Mplus and the lavaan/semTools packages. Structural Equation Modeling: A

Multidisciplinary Journal, 27(1), 111–130.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2019.1602776

Tahmassian, K., & Jalali, N.

(2011). Relationship between self-efficacy and symptoms of anxiety, depression,

worry and social avoidance in a normal sample of students. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 5(2),

91-98.

Tak, Y. R., Brunwasser, S. M., Lichtwarck-Aschoff, A., & Engels, R. C. (2017). The

prospective associations between self-efficacy and depressive symptoms from

early to middle adolescence: A cross-lagged model. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(4), 744–756. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0614-z

Tsamakis, K., Tsiptsios, D., Ouranidis, A., Mueller, C., Schizas,

D., Terniotis, C., Nikolakakis,

N., Tyros, G., Kympouropoulos, S., Lazaris, A., Spandidos, D. A., Smyrnis, N., & Rizos, E.

(2021). COVID-19 and its consequences on mental health (Review). Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine, 21(3),

244. https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2021.9675

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural

Organization. (2020). Distance learning

strategies in response to COVID-19 school closures.

https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373305

Wainberg, M., Scorza, P., Shultz,

J., Helpman, L., Mootz, J., Johnson, K., Neria, Y., Bradford, J., Oquendo, M., & Arbuckle, M.

(2017). Challenges and opportunities in global mental health: A

research-to-practice perspective. Current

Psychiatry Reports, 19(5), 28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-017-0780-z

Wang, C., Wen,

W., Zhang, H., Ni, J., Jiang, J., Cheng, Y., Zhou, M., Ye, L., Feng, Z., Ge,

Z., Luo, H., Wang, M., Zhang, X., & Liu, W. (2021). Anxiety, depression,

and stress prevalence among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal

of American College Health. Advance online publication.

https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2021.1960849

Wang, J., &

Wang, X. (2020). Structural equation

modeling: Applications using Mplus (2nd

Ed.). Wiley

Werner, A. M., Tibubos, A.

N., Mülder, L. M., Reichel, J. L., Schäfer, M.,

Heller, S., Pfirrmann, D., Edelmann,

D., Dietz, P., Rigotti, T., & Beutel,

M. E. (2021). The impact of lockdown stress and loneliness during the COVID-19

pandemic on mental health among university students in Germany. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 22637. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-02024-5

Widaman, K. F., & Revelle, W.

(2022). Thinking thrice about sum scores, and then some more about measurement

and analysis. Behavior Research Methods.

Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-022-01849-w

World Health Organization. (2022, June 17). Mental health: Strengthening our response. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response

Wu, H., & Estabrook, R. (2016). Identification of

confirmatory factor analysis models of different levels of invariance for

ordered categorical outcomes. Psychometrika,

81(4), 1014–1045. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11336-016-9506-0

Xiong, J., Lipsitz, O., Nasri, F., Lui, L., Gill,

H., Phan, L., Chen-Li, D., Iacobucci, M., Ho, R.,

Majeed, A., & McIntyre, R. S. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental

health in the general population: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 277, 55–64.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001

Yokoyama S. (2019). Academic self-efficacy and

academic performance in online learning: A mini review. Frontiers in Psychology,

9, 2794. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02794