http://dx.doi.org/10.24016/2023.v9.284

ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

Suicide risk model

based on the interpersonal theory of suicide: evidence in three regions of

Mexico

Modelo de riesgo suicida basado en la teoría interpersonal del

suicidio: evidencia en tres regiones de México

Modesto Solis-Espinoza

1, Juan Manuel Mancilla-Díaz 1, Rosalía Vázquez-Arévalo 1

1 Facultad de

Estudios Superiores Iztacala, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México,

Iztacala, Mexico.

* Correspondence: modesto333_3@hotmail.com.

Received: August 23, 2022 | Revised: November 14, 2022 | Accepted:

February 16, 2023 | Published online: February 23, 2023.

CITE IT AS:

Solis-Espinoza, M., Mancilla-Díaz, J., &

Vázquez-Arévalo, R. (2023). Suicide risk model based on the interpersonal theory of suicide:

evidence in three regions of Mexico. Interacciones, 9,

e284. http://dx.doi.org/10.24016/2023.v9.284

ABSTRACT

Background: Reports of suicidal behavior

have increased in Mexico for years. In order to develop a more adequate suicide

prevention strategy, it is necessary to understand its predictive factors, so

the purpose of this research was to propose a model of suicidal risk in young

people, taking into account one of the most current theories on the subject,

Joiner's interpersonal theory. Method: A non-probabilistic sample of young people with

suicidal ideation from three regions of Mexico was obtained by online survey

(N=411), with mean age of 17.89 years (SD. 1.2), 336 women (81.8%), and 75 men

(18.2%). Results: First, a multiple linear regression model was created

to predict suicidal risk based on thwarted belongingness and perceived burden

with 17% explained variance; then a second model was generated with the same

variables and including other factors associated with suicide such as

self-injury desires, impulsivity and suicide attempts, in addition to variables

associated with family conflicts, improving the explained variance to 34%.

Lastly, two properly adjusted structural equation models were obtained, one

focused on suicidal risk (R2=.21; RMSEA=.026; CFI=.99) and the other

on ideation (R2=.18; RMSEA=.070; CFI=.98). Conclusions: The main factors that

explain suicidal risk are depressive symptoms, perceived burden and desires for

self-injury. Further research on the effect of painful experiences as factors

that could predict suicide attempt is suggested.

Keywords: suicide, interpersonal theory, self-injury, thwarted

belongingness, perceived burdensomeness.

RESUMEN

Introducción: Los reportes de conducta suicida en México

han aumentado por años. Para desarrollar una estrategia más adecuada de

prevención del suicidio es necesario comprender sus factores predictores, por

lo que el propósito de la presente investigación fue proponer un modelo del

riesgo suicida en jóvenes tomando en cuenta una de las teorías más vigentes en

cuanto al tema, la teoría interpersonal de Joiner. Método: Se obtuvo por encuesta online una muestra no

probabilística de jóvenes con ideación suicida de tres regiones de México

(N=411), con una edad media de 17.89 años (DE. 1.2), 336 mujeres (81.8%) y 75

hombres (18.2%). Resultados: Primero se conformó

un modelo de regresión lineal múltiple para predecir riesgo suicida a partir

del sentido de pertenencia frustrado y la carga percibida con 17% de varianza

explicada; después se generó un segundo modelo con las mismas variables e

incluyendo otros factores asociados al suicidio como los deseos de autolesión,

impulsividad e intentos suicidas, además de variables asociadas a conflictos

familiares, mejorando la varianza explicada hasta un 34%. Por último, se

obtuvieron dos modelos de ecuaciones estructurales con ajuste adecuado, uno

enfocado en riesgo suicida (R2=.21; RMSEA=.026; CFI=.99) y otro en

la ideación (R2=.18; RMSEA=.070; CFI=.98). Conclusiones: Los principales factores que explican el

riesgo suicida son los síntomas depresivos, la carga percibida y los deseos de

autolesión, se sugiere seguir investigando sobre el efecto de experiencias

dolorosas como factores que podrían predecir el intento suicida.

Palabras clave: suicidio, teoría interpersonal, autolesiones, carga percibida,

sentido de pertenencia frustrado.

BACKGROUND

The prevalence of suicides in Mexico has been on an upward trend for

approximately two decades (Fernández et al., 2016; National Institute of

Statistics, Geography and Informatics (2020, 2021), a fact that could be

exacerbated when considering the psychosocial effects of the pandemic of

COVID-19, the estimates that have been made in other countries such as the

United States, China, Bangladesh and the United Kingdom with people in a wide

range of ages (15-75 years), point to a prevalence of 11.5% with suicidal

ideation in the general population, a higher percentage than is usually

reported prior to the pandemic (Farooq et al., 2021).

The previous trend combines with what was recorded by the National

Survey of Health and Nutrition (ENSANUT) 2018, in which it refers that 5% of

the population over 10 years old has ever thought about committing suicide,

more specifically in the adolescent population (10 to 19 years old) 4% in men

and 7% in women, and in the young population (20 to 29 years old) 4% in men and

5% in women.

It has been analyzed that the impact of the pandemic on the suicide

spectrum can be economic, social and biological (Conejero

et al., 2020), with psychological consequences that could impact suicide rates

during the pandemic and even after (Sher, 2020), as has been verified in the

significant increase in the number of consultations due to suicide ideas and

attempts (Jerónimo et al., 2021), or in the increase

in mortality due to suicide, even in countries with a relatively small impact

of COVID -19 (Watanabe and Tanaka, 2022). With this panorama, it is necessary

to test models that explain suicidal risk, which allow guiding prevention and

clinical supported on theoretical empirical bases about suicide.

Along this line, some models have already been generated to predict

suicide in the Latin American context, such is the case of the contribution of

Toro et al. (2021), who created a cross-cultural model with a proven good fit

with Mexican and Colombian adult population, giving a special emphasis to the

explanation of suicidal risk from depression, despair and suicidal ideation.

On the other hand, a predictive model of suicidal ideation in Mexican

adolescents from Jalisco was also recently revealed (Reynoso et al., 2019),

which managed to explain 30.7% of the variance, having as predictor variables

in depressive symptoms, lack of family support and problems adjusting to school

in order of relevance.

After the COVID-19 pandemic, it is necessary to involve aspects such as

the case of despair about the future and changes in social reciprocity (Banergee et al., 2021), which is why the high explanatory

potential of the interpersonal theory of Joiner (2005), one of the most current

theories regarding the explanation of suicide that has been tested both in

clinical samples (Joiner et al., 2009) and in non-clinical ones (Becker et al.,

2020).

The theory of Joiner is based on the interaction of three variables, the

perceived burden (feeling like a burden to others), the thwarted belongingness

(not perceiving oneself as part of any group), and the acquired capacity for

suicide (absence of fear of dying and high pain tolerance), according to the

theory the first two variables will result in the desire to die (Van Orden et

al., 2010), however, the possibility and lethality of the attempt are

determined by the acquired capacity for suicide, which is explained by

habituation processes and the opposite process (Solomon, 1998), constant

painful experiences could make it less intimidating to try to commit suicide.

There are systematic reviews of the studies that test this theory,

yielding controversial results, for example Ma et al. (2016) point out that the

perceived burden influences suicidal ideation, that the perceived burden in the

interaction with the thwarted belongingness with suicidal ideation are modest,

while the relationship with suicidal capability has been low. In a more or less

similar way, Klonsky et al. (2016) found significant and robust associations

between thwarted belongingness and the perceived burden with suicidal ideation,

and acquired suicidality related to a greater number of suicide attempts,

although points out that the operational definition of suicidal capability

could be influencing so that larger effect sizes are not obtained.

Similarly, other studies partially support Joiner's (2005) postulates,

pointing out that it is necessary to continue exploring the interaction of its

main constructs with gender-specific effects and other psychological processes

(Cha et al., 2018); just as it has been mentioned that the perceived burden and

the thwarted belongingness influence suicidal ideation differently in their

interaction with other factors, underlining the importance of studying this

theory associated with other aspects of suicidal behavior (Espinosa-Salido et al., 2020).

According to Chu et al., (2017) there is a lack of studies that test the

interpersonal theory with validated instruments, in addition to recommending

the application with adolescents, understanding that there is a high number of

suicidal behaviors and they can last until death. Adulthood, which makes

special sense in light of the latest epidemiological reports (INEGI, 2021), in

which the age group with the highest suicide rate is the one of people between

18 and 29 years old, 10.7 deaths per 100,000 people.

Just as there are studies that have directly explored the interpersonal

theory of suicide, there are also studies that have reported data that could

appear to be evidence of Joiner's (2005) statements, such as have suffered

health damage due to violence implies a greater risk of suicide attempt

compared to those who have not (Valdéz-Santiago et

al., 2018), which could be related to the

acquired capacity for suicide due to habituation to painful experiences, in the

same way as with research on suicide and its link with behavior.

In another

study, those with a mild eating disorder score reported 1.5 times more likely

to attempt suicide, while those with moderate scores had 4.2 times more likely

to attempt suicide compared to those without eating psychopathology (Valdéz-Santiago et al., 2018). In turn, it has been

possible to distinguish between young people with suicidal ideation and

behavior based on exposure to self-harm among friends and/or relatives,

psychological disorders, and the use of cigarettes and drugs (except cannabis)

(Mars et al., 2019), findings that point in the same direction as that

postulated regarding the acquired capacity for suicide (Van Orden et al.,

2010), assuming that exposure to painful behaviors can facilitate a reduction

in fear towards them and therefore, a greater risk of attempting against one's

own life.

As a complementary way to what was proposed by Joiner

(2005), it has been proposed that in addition to the acquired capacity for

suicide, there are more variables that determine the passage from ideation to

suicide attempt, as in the case of self-destructive behaviors of others serving

as modeling and impulsivity among other variables (O´Connor & Kirtley, 2018).

Taking into account the above, factors associated with

relevant suicidal behavior in its prediction have been included in this project,

as is the case of self-injury (Serra et al., 2022), or the case of depressive

symptomatology (Melhem et al., 2019; Sandoval et al.,

2018). The objective was to propose a model of suicidal risk in young people

based on Joiner's interpersonal theory, in adolescents with suicidal ideation

from different regions of Mexico.

METHODS

Participants

A non-probabilistic sample was obtained from young

people with suicidal ideation (non-specific active suicidal thoughts) N=411

with an M=17.89 years (SD. 1.2), in an age range between 13 and 20 years old,

336 women (81.8%) and 75 men (18.2%), the participants came from cities in

three regions of Mexico, Mexico City (n=155) and State of Mexico (n=102),

“central zone”; Guadalajara (n=86) “western area”, and Tijuana (n=68),

“northern area”. Regarding schooling, 50.6% reported studying high school

level, 26.3% university, 5.6% reported secondary level and 17.5% reported not

studying at the time of their participation.

Instruments

General data: sociodemographic aspects such as age, schooling,

substance use, and relationship with family and school environment.

Plutchik's Suicide Risk Scale (Plutchik & Van Praag, 1989; adapted to Spanish by Rubio et al., 1998). It

consists of 15 items with yes/no answers, the sum of 6 affirmative answers

implies the presence of suicidal risk (Rubio et al., 1998). The modified version

of two items by Suárez-Colorado et al. (2019) was used. Internal consistency in

Mexicans has been Cronbach's Alpha of .74 (Santana-Campas

& Santoyo, 2018) and up to .84 (Solis-Espinoza, 2021).

Beck's Depression Inventory (BDI - II) (Beck et al., 1996; adapted for the Mexican

population by Jurado et al., 1998). It consists of 21 items that evaluate

depressive symptoms with a descriptive scale of four options, it has a high

reliability with Cronbach's alpha of .89 (Padrós

& Pintor, 2021).

Columbia Scale to Assess the

Seriousness of Suicidal Ideation (C-SSRS) (Posner et al., 2011; adapted to Spanish by Al-Halabí et al., 2016). It is a semi-structured interview

that evaluates: 1) severity of suicidal ideation with 5 types of ideation with

a 5-point ordinal scale (from 1=desire to die to 5=suicidal ideation with a

specific plan or intention), 2) intensity of ideation made up of ordinal scales

(frequency, duration, controllability, deterrence, and reason for ideation), 3)

suicidal behavior with a nominal scale of actual, interrupted, and aborted

attempts, preparatory acts, and nonsuicidal

self-destructive behavior, and 4) the lethality of suicidal ideation, suicidal

behavior, the scale has shown evidence of adequate discriminant validity and

sensitivity to change. Sensitivity to change: the reduction of one point in

item 3 of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale implied 5.08 points fewer in the

severity of suicidal ideation and 13.51 points fewer in the intensity of

suicidal ideation. The intensity of suicidal ideation obtained a Cronbach's

alpha of .53, the factors of intensity of suicidal ideation explained 55.66% of

the variance (Al-Halabí et al., 2016).

Interpersonal Needs

Questionnaire (Van

Orden et al., 2008; adapted to Spanish by Ordoñez-Carrasco,

et al., 2018). Instrument developed to test Joiner's interpersonal theory of

suicide. There are 10 items on a Likert scale with 7 response options, from 1

(not very true for me) to 7 (very true for me). It has two subscales: perceived

burden with an alpha of .92 (feeling of being "a burden" for other

people) and thwarted belongingness with an alpha of .80 (feeling that one is

not part of anything) (Ordoñez-Carrasco, et al.,

2018).

Scale of acquired capacity

for suicide (lack of fear of dying) (Ribeiro et al., 2014; adapted by Trejo, 2018). 8-item

scale that estimates fearlessness to hurt oneself with 5 response options, from

1 (not at all like me) to 5 (very much like me). In the Mexican population, a

Cronbach's alpha of .76 has been reported (Trejo, 2018).

Self-harm risk questionnaire (CRA) (Solis & Gómez-Peresmitré,

2020). The self-injury frequency factor and the addictive effect of

self-injury/desire for self-injury were used, consisting of 9 dichotomous and

polytomous questions, with high internal consistency (alpha and omega = .94)

(Solis & Gómez-Peresmitré, 2020).

Plutchik's Impulsivity Scale (Plutchik & Van Praag, 1989; adaptation to Spanish by Rubio et al., 1998).

It consists of 15 items that measure impulsive behavior on a Likert-type scale

with 4 response options ranging from never to almost always. Adequate

reliability has been reported (Cronbach's alpha = .71) (Alcázar-Córcoles

et al., 2015).

Procedure

A web page created on GoogleForms

was distributed through social networks, in which the different instruments

were included; at the beginning, an informed consent was presented with the

description of the project, stating that participation would be voluntary and

the data would be used only for research purposes, later, each section of

general questions and the instruments were presented, one week after answering

the survey feedback and report of results were sent by email to each

participant, suggesting that they receive psychological support in cases where

there were indications of psychopathology (for example, high suicidal risk

score or active suicidal ideation), they were provided a list of public

psychological support centers to receive care and followed up on cases in which

they requested support and/or more information. The data collection was non-invasive

and the ethical criteria for research in psychology (SMP, 2007) were followed.

Analysis of data

Measures of central tendency of the variables were

obtained. Afterwards, the assumptions of variance homogeneity (Levene test) and normality (Kolmogorov-Smirnov) of the

sample were tested in order to perform the analysis of variance of one factor

(ANOVA), with the aim of looking for differences according to the region of the

participants. Although not all the variables obtained a normal distribution, some

authors point out that if this assumption is not drastically violated, the

ANOVA works adequately (Zar, 2010). Then multiple

linear regressions and structural equations were used to create models that

explained suicide risk, with the Generalized Least Squares estimator. For the

size of the sample, the recommendations of Vargas-Halabí

(2016). The cut-off points of the adjustment indices were considered: RMSEA≤.08

(Browne & Cudeck, 1993); GFI≥.90

; CFI≥ .95 (Lai, 2021); IFI≥.90 (Bollen,

1989). SPSS V.21 and AMOS V.21 were used.

Ethics topics

This project had the

approval of the Comité de ética de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de

México - Facultad de Estudios Superiores Iztacala (no. 1417).

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the comparisons (simple variance

analysis), the average, and the standard deviation of the main variables of the

study in the sample according to the entity of origin.

|

Table 1. Comparisons of variables related to

suicide according to the state of origin. |

||||||||||

|

Ciudad

de México (n= 155) |

Estado

de México (n=102) |

Jalisco

(n = 86) |

Tijuana

(n= 68) |

ANOVA |

||||||

|

Variable |

M |

SD |

M |

SD |

M |

SD |

M |

SD |

F |

η2 |

|

Suicidal risk |

25.67 |

1.92 |

25.62 |

2.06 |

26.32 |

1.73 |

25.76 |

2.05 |

2.56 |

0.010 |

|

Depressive symptoms |

52.89 |

11.75 |

54.46 |

10.66 |

55.31 |

8.01 |

54.02 |

10.79 |

1.05 |

0.008 |

|

Perceived burden |

29.83 |

10.47 |

30.29 |

10.86 |

31.08 |

10.59 |

28.55 |

10.78 |

0.75 |

0.005 |

|

Thwarted belongingness |

17.68 |

5.89 |

18.50 |

6.32 |

19.10 |

5.46 |

18.04 |

6.25 |

1.14 |

0.008 |

|

Impulsivity |

39.45 |

5.70 |

39.73 |

6.36 |

41.56 |

5.63 |

39.41 |

6.63 |

2.64* |

0.010 |

|

No fear of dying |

26.49 |

7.26 |

24.99 |

6.43 |

25.82 |

6.98 |

27.25 |

7.26 |

1.66 |

0.010 |

|

Desire to self-injury |

11.84 |

4.16 |

11.56 |

4.66 |

12.12 |

3.95 |

11.91 |

4.58 |

0.26 |

0.002 |

|

Suicidal attempts |

1.83 |

1.91 |

1.71 |

1.92 |

1.80 |

2.00 |

2.21 |

2.72 |

0.83 |

0.006 |

|

Intensity of suicidal ideation |

14.18 |

3.65 |

14.68 |

3.77 |

15.62 |

4.03 |

15.05 |

4.36 |

2.72* |

0.020 |

|

Family problems |

3.00 |

0.83 |

3.22 |

0.91 |

3.13 |

0.89 |

3.35 |

0.85 |

2.89* |

0.020 |

|

Note: sig. * p<.05 |

||||||||||

Upon concluding that most of the variables did not

differ significantly according to each subsample, and in the cases in which

there were differences, the effect size was small, the analyzes were performed

as a whole, as a single sample. Two models with multiple linear regression (see

Table 2) were hypothesized to test some postulates of the interpersonal theory

of suicide, predicting suicidal risk, a first model of the perceived burden and

thwarted belongingness was developed with 17% of explained variance. Being one

of the key factors within the interpersonal theory of suicide, the absence of

fear of dying was included in the regression models, however, it did not have a

significant effect. Subsequently, variables that could be associated with the

acquired capacity for suicide were added (previous suicide attempts,

impulsivity, the desire to self-injury, and family violence), and a variable

that could be associated with thwarted belongingness (quality of the family

relationship), the second model achieved an explained variance of 34%, with the

main predictors being the desire to harm oneself (β=.26), the perceived burden

(β=.17) and the number of suicide attempts (β=.19).

|

Table 2. Multiple linear regression models for Suicidal

risk. |

||||||

|

Non-standardized coefficients |

Standardized coefficients |

|||||

|

|

|

β |

Error típ. |

β |

t |

p |

|

Model 1 |

(Constant) |

22.84 |

0.36 |

62.92 |

0.001 |

|

|

Perceived burdensomness |

0.07 |

0.01 |

0.38 |

8.47 |

0.001 |

|

|

|

Thwarted belongingness |

0.05 |

0.02 |

0.15 |

3.25 |

0.001 |

|

Model 2 |

(Constant) |

19.61 |

0.69 |

28.49 |

0.001 |

|

|

Perceived burdensomness |

0.03 |

0.01 |

0.18 |

3.86 |

0.001 |

|

|

Thwarted belongingness |

0.04 |

0.01 |

0.11 |

2.65 |

0.008 |

|

|

No fear

of dying |

-0.01 |

0.01 |

-0.05 |

-1.09 |

0.275 |

|

|

Domestic violence |

0.33 |

0.14 |

0.12 |

2.36 |

0.019 |

|

|

Impulsivity |

0.04 |

0.01 |

0.11 |

2.73 |

0.007 |

|

|

Desires of self-injury |

0.12 |

0.02 |

0.26 |

5.62 |

0.001 |

|

|

No. of

suicide attempts |

0.19 |

0.04 |

0.20 |

4.53 |

0.001 |

|

|

|

Family problems |

0.25 |

0.11 |

0.11 |

2.29 |

0.022 |

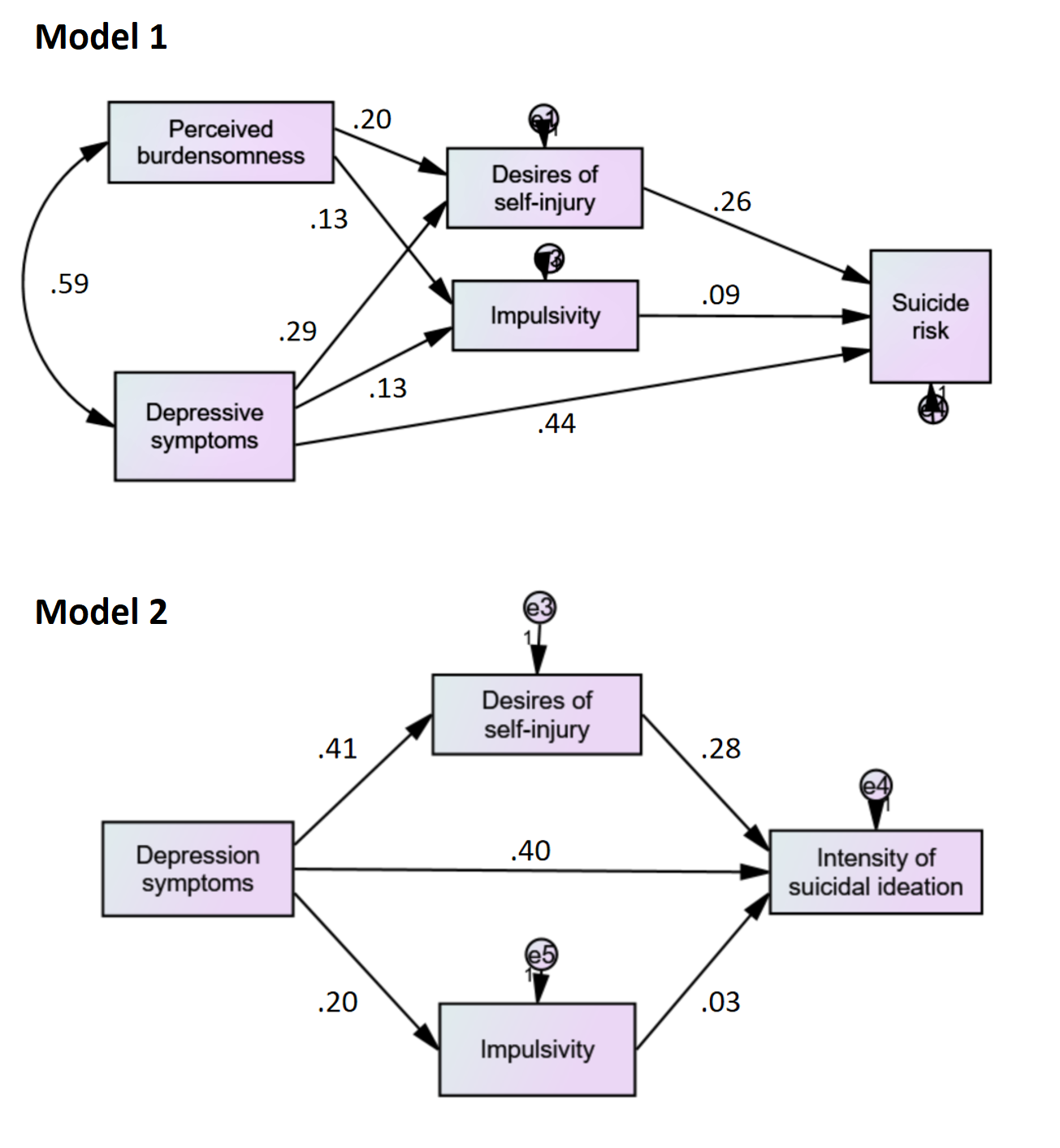

After the development of regression models, two models

were proposed using structural equations, considering some of the previous

results, taking the suicidal risk as the dependent variable in the first, and

the intensity of ideation second in the second (see Table 3). Figure 1 shows

the models.

|

Table 3. Goodness-of-fit indices of the models

(n=411). |

|||||||||

|

|

X2 |

df |

p |

RMSEA |

AIC |

R2 |

CFI |

GFI |

IFI |

|

Model 1.

Suicide risk prediction |

2.544 |

2 |

0.28 |

0.03 |

28.5 |

0.21 |

0.99 |

0.99 |

0.99 |

|

Model 2. Prediction of the intensity of

suicidal ideation |

3.003 |

1 |

0.083 |

0.07 |

21.0 |

0.18 |

0.98 |

0.99 |

0.98 |

|

Note: X2 = Chi

squared. df = Degrees of

freedom. CFI = Comparative fit index. TLI = Tucker-Lewis index. RMSEA = Root mean square error of

approximation. SRMR = Standardized root mean square residual. |

|||||||||

Figure 1. Path analysis.

Note: Model 1 = Suicide risk prediction. Model 2 =

Prediction of the intensity of suicidal ideation.

DISCUSSION

The objective of the study was to propose a model that

explains the suicidal risk in young people based on the principles of the

interpersonal theory of Joiner (2005), two multiple linear regression models

were carried out, one testing the hypothesis that the perceived burdens and the

thwarted belongingness would be associated with suicidal risk with 17% explained

variance and one in which the addition of other associated variables was tested

reaching 34% explained variance. Subsequently, two path analysis models with

acceptable adjustable indices were proposed, one taking suicide risk as a

variable to predict (R2=.21; RMSEA=.026; CFI=.99) and another

predicting the intensity of suicidal ideation (R2=.18, RMSEA=.070,

CFI=.98).

What was found in the multiple linear regression

models is consistent with one of the hypotheses proposed in the work of Van

Orden et al., (2010), in which it is pointed out that the variables of

perceived burden and thwarted belongingness can have an impact on their own

alone in the development of ideas about suicide, however, the effect seems

unequal, with the effect of the perceived burdensomeness (.38) being more than

the double that the thwarted belongingness (.14) on suicidal risk; this finding

could be explained by taking into account what was pointed out by Espinosa-Salido et al., (2020), both factors, despite being

interrelated and having proven to be good predictors of suicide attempts, have

also contributed to some predictive models independently and in interaction

with other variables. Another result that could be associated with the thwarted

belongingness is the relationship with the family, a factor added in the second

regression model that had a significant impact (Domestic violence β=.11; Family conflicts β=.11), from it could be hypothesized that a family

relationship considered "good" would serve as a protective factor against

suicide, insofar as this would reflect a sense of belonging with family

members.

In contrast to the first two elements of the

interpersonal theory of suicide, the effects of the absence of fear of dying

did not have a significant impact on the predictive models, similar to what was

reported by Becker, Foster and Luebbe (2020), who

found moderate to high correlations between suicidal risk with thwarted

belongingness (.41), with perceived burdensomeness (.52), with depressive

symptomatology (.55), and lower correlations with the absence of fear of dying

(.06).

In another study (Schuler et al., 2021), although low

levels of suicidal ideation were associated with low suicide capacity, it was

emphasized that the acquired capacity for suicide did not show significant

variations over 90 days, suggesting that it is of a factor that tends to be

stable, so it would not be entirely clear how this aspect would be involved in

suicide prevention, even pointing out that genetic aspects and other variables

could influence suicidal ability.

Following the same trend, Wolford-Clevenger et al.,

(2020) confirmed the hypothesis of Van Orden et al., (2010) regarding the

association between the perceived burden and thwarted belongingness with

suicidal wishes, despite little support for the relationship with the acquired

capacity for suicide, from which it is suggested to consider new

conceptualizations of that construct in the measurement of the variables, such

as the proposal by Klonsky and May (2015) with two other variables that

contribute to the capacity to commit suicide: practical (knowledge and access

to lethal means to take one's life) and dispositional (genetic aspects such as

sensitivity to pain, fear of blood, fearless traits).

On the other hand, the results were consistent with

the studies that support the relationship between self-injury and suicidal

behavior, according to a review of studies that analyzed this association (Grandclerc et al., 2016), the authors point out that

self-injury has been linked to suicide from some theories as a

"gateway" in this continuum, it has also been addressed with the

theory of a "third variable" in which comorbidity with other relevant

factors between self-injury and suicide is assumed, and, Predominantly, it has

been associated in recent years with the acquired capacity for suicide,

habituation to pain and less fear of death.

The result obtained regarding self-injury seems to

coincide with that found by Burke et al., (2018), in which the frequency of

self-injury turned out to be a discriminating variable between groups with

suicidal ideation and different degrees of planning and intention to die,

similarly, other pain-provoking events such as the experience of childhood

emotional abuse, physical abuse and physical neglect, for which the authors

suggest considering them as factors to be evaluated when exploring the

transition from ideation to suicidal behavior. On the other hand, they did not

find a significant difference when comparing the groups with a scale of

acquired capacity for suicide, similar to what was obtained in the present

study, considering the number of suicide attempts and

family violence as painful experiences that facilitate suicidal capacity

independently of the absence of fear of dying.

Based on these results, it could be hypothesized that

the evaluation of the acquired capacity for suicide does not contribute as much

to the explanation of suicidal risk as the pain-provoking experiences do,

however, as a line of research to be developed, the effects of these events regardless

of the pain caused and if they generate less/greater fear of death. As an

example of this, the frequency of self-injury according to what is postulated

in the theories of ideation to action, would represent a means of habituation

to pain and therefore to suicide attempt, however, self-injury by concept is

associated with the attempt to regulate negative emotions (Gratz & Roemer,

2008; Wolff et al., 2020), from which it could be inferred that perhaps the

main effect on suicidal risk is not through pain tolerance, but from coping

style, emotional dysregulation and the events that have triggered the negative

emotions previously.

The first path model of this study may have

similarities with the "three-step" approach of Klonsky and May

(2015), in which the presence of pain and hopelessness, the lack of connection

and the suicidal capacity are considered determinants so that the attempt is

reached. In this study, depressive symptoms and perceived burdensomeness are

correlated factors (.59) that would play a role similar to that of pain and

hopelessness, with a direct influence on suicidal risk in the case of

depressive symptoms (β=.44) and as well as different effects on

the desire for self-injury and impulsivity, which is a variable that triggers

suicide attempts (O'Connor & Kirtley, 2018); both

factors associated with suicidal capability with direct influence on suicidal

risk (desires for self-injury β=.26; impulsivity β=.09). The second proposed model takes up some

elements and obtains a similar adjustment even without considering aspects

associated with the perceived burden or the social belonging of the

interpersonal theory of suicide.

Given the role played by the addictive effect of

self-injury/desire to self-harm in both models (β = .26 in the suicide risk model; β = .28 in the intensity of suicidal ideation model),

it is necessary to continue directing more research to this concept, facing the

positions that disassociate self-injury from suicide, considering different

associated aspects regardless of the habituation of pain (Joiner, 2005). At the

same time, it is recommended for future projects to develop different ways of

evaluating the acquired capacity for suicide and analyze in greater depth the

relevance that the absence of fear of dying might or might not have.

Among the main contributions of this study, in

contrast to other projects, is the type of sample used, since it is even a

community sample, the indicators obtained represent high levels of depressive

psychopathology and suicidal risk, with 65.9% of participants with a record of

suicide attempts, which has allowed predictive estimates to be made in a

population that actually has suicidal thoughts, and that thanks to the project

have received an assessment; although it was not the objective of this study,

it is worth mentioning that qualitative information was collected and various

questions and problems expressed by the participants were answered, both

specific problems and advice on seeking psychological support. In addition, the

models obtained seem to be valid in adolescents from different regions, as it

is verified that relevant factors of suicide did not differ significantly

beyond the possible cultural differences derived from the different social

environments.

Some authors (Chu et al., 2017) have pointed out that

smaller effect sizes are usually found when suicide research is not based

solely on the web, so it could be deduced that the privacy and anonymity of

social networks could be providing more reliable information, less susceptible to

effects of social desirability, in such a way those information gathering

strategies could be maintained in a virtual format even without the impediment

to carrying out face-to-face evaluations; In addition to the fact that some

preventive strategies have already been developed within virtuality, an example

of this has been focusing on social connectivity as a protection factor,

through the creation of safe environments in spaces such as Reddit (McAuliffe

et al., 2022).

Suicide is complex and multifactorial, so it requires

an approach that is not limited only to psychopathology, it is necessary that

prevention considers the socioeconomic and cultural context (Gómez-García et

al., 2022; Navarrete et al., 2019 ), in this sense, it is essential to prevent

suicide to move towards multidisciplinary approaches that are not only the

responsibility of public health instances, it is necessary to promote laws and

a legal framework that allows establishing solid strategies against suicide in

favor of mental health (Valdéz-Santiago et al.,

2021).

Public health implications

Although previous suicide attempts, among other

variables, are clearly identified as risk factors (Gómez, et al., 2019;

Wilkinson et al., 2011), there are other variables such as desires of

self-injury and perceived burdensomeness, which possibly need to be considered

more frequently when examining young people in risk. The relevance of this type

of study lies in the possibility of refining and promoting early prevention

strategies, with the support of current scientific findings, which implies

specifying clear action guidelines from mental health institutions.

Limitations

As a main limitation, it would be mentioned that given

the nature of a cross-sectional study, aspects related to the temporality and

stability of the variables studied could not be evaluated, in addition to the

fact that there was no other resource to corroborate or confirm the scores

obtained like an interview. In addition to the fact that an exhaustive

measurement of pain-provoking experiences or a direct evaluation was not

carried out to estimate objective tolerance to pain, which would be essential

in this line of research if the acquired capacity for suicide continues to be

studied. Finally, it is necessary to point out that the present study was

carried out under the conditions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, so it could

be assumed that there are important changes in terms of the responses given by

the participants, it will be up to future research to continue analyzing the

possible effects of confinement by the health emergency, as well as to compare

the models proposed in this study in other samples and under different

conditions.

ORCID

Modesto Solis Espinoza https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9043-4245

Juan Manuel Mancilla Díaz https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7259-3667

Rosalía Vázquez Arévalo https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6491-9639

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTION

Modesto Solis Espinoza: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis,

investigation, writing review & editing, funding acquisition.

Juan Manuel Mancilla Díaz: validation,

resources, supervision, funding acquisition.

Rosalía

Vázquez Arévalo: methodology, resources, supervision.

FUNDING SOURCE

This research was

supported by Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México

(Programa de Becas Posdoctorales en la UNAM).

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare

that there were no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Not applicable.

REVIEW PROCESS

This study has been

reviewed by external peers in double-blind mode. The editor in charge was Jeff Huarcaya-Victoria. The review process is included as

supplementary material 1.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Not applicable.

DISCLAIMER

The authors are

responsible for all statements made in this article.

REFERENCES

Alcázar-Córcoles, M. A., Verdejo, A. J., &

Bouso-Saiz, J. C. (2015). Propiedades

psicométricas de la escala de impulsividad de Plutchik

en una muestra de jóvenes hispanohablantes.

Actas españolas de Psiquiatría, 43(5), 161-169.

Al-Halabí, S., Sáiz, P. A., Burón, P., Garrido, M., Benabarre, A.,

Jiménez, E., Bobes, J. (2016). Validación de la versión en español de la

Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale

(Escala Columbia para Evaluar el Riesgo de Suicidio). Revista de Psiquiatria y Salud Mental, 9,

134–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rpsm.2016.02.002

Banerjee, D., Kosagisharaf, J. R., & Sathyanarayana

Rao, T. S. (2021). 'The dual pandemic' of suicide

and COVID-19: A biopsychosocial narrative of risks and prevention. Psychiatry research, 295, 113577. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113577

Becker,

S. P., Foster, J. A., & Luebbe, A. M. (2020). A

test of the interpersonal theory of suicide in college students. Journal of affective disorders, 260,

73–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.09.005

Bollen, K.A. (1989). Structural

Equations with Latent Variables. John Wiley and Sons, Inc., New York.

https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118619179

Browne,

M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of

assessing model fit On K. A Bollen & J. S. Long

(Eds), Testing structural equation models (pp 136-162) Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Burke, T. A., Ammerman, B. A., Knorr, A. C., Alloy, L.

B., & McCloskey, M. S. (2018). Measuring Acquired Capability for Suicide

within an Ideation-to-Action Framework. Psychology of violence, 8(2),

277–286. https://doi.org/10.1037/vio0000090

Cha, C. B., Franz, P. J., M Guzmán, E., Glenn, C. R.,

Kleiman, E. M., & Nock, M. K. (2018). Annual Research Review: Suicide among

youth - epidemiology, (potential) etiology, and treatment. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry,

and allied disciplines, 59(4),

460–482. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12831

Chu, C., Buchman-Schmitt, J. M., Stanley, I. H., Hom, M. A., Tucker, R. P., Hagan, C. R., Rogers, M. L., Podlogar, M. C., Chiurliza, B.,

Ringer, F. B., Michaels, M. S., Patros, C., &

Joiner, T. E. (2017). The interpersonal theory of suicide: A systematic review

and meta-analysis of a decade of cross-national research. Psychological bulletin, 143(12), 1313–1345. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000123

Conejero, I., Berrouiguet, S.,

Ducasse, D., Leboyer, M., Jardon, V., Olié, E., & Courtet, P.

(2020). Épidémie de COVID-19 et prise en charge des conduites suicidaires : challenge et perspectives [Suicidal behavior in

light of COVID-19 outbreak: Clinical challenges and treatment

perspectives]. L'Encephale, 46(3S), S66–S72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.encep.2020.05.001

Espinosa-Salido, P., Pérez, N. M. A.,

Baca-García, E., & Ortega, M. P. (2021). La revisión sistemática de la

relación indirecta entre la pertenencia social frustrada y la sensación de ser

una carga en el suicidio. Clínica y Salud, 32(1), 29-36. https://dx.doi.org/10.5093/clysa2020a27

Farooq S, Tunmore J, Wajid

Ali M, Ayub M. Suicide, self-harm and suicidal

ideation during COVID-19: A systematic review. Psychiatry Research. 306 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114228

Fernández, J.

, Astudillo, C. , Bojorquez, I. , Morales, E.

, Montoya, A. & Palacio, L. (2016). The Mexican cycle of suicide: A national analysis of

seasonality, 2000-2013. Plos one, 11(1), 1-20. doi:

10.1371/journal.pone.0146495.

Gómez-García, L.,

Arenas-Monreal, L., Valdez-Santiago, R., Rojas-Russell, M., Astudillo-García,

C.I., & Agudelo-Botero, M. (2022). Barreras para la atención de las

conductas suicidas en Ciudad de México: experiencias del personal de salud en

el primer nivel de atención. Revista

Facultad Nacional de Salud Pública. 40(1) doi: https://doi.org/10.17533/udea.rfnsp.e346540

Gómez, A., Núñez, C., Caballo,

V. E., Agudelo, M. P., &

Grisales, A. M. (2019). Predictores psicológicos del riesgo suicida en

estudiantes universitarios. Behavioral Psychology.

27(3), 391-413.

https://www.behavioralpsycho.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/03.Gomez-27-3oa-1.pdf

Grandclerc, S., De

Labrouhe, D., Spodenkiewicz,

M., Lachal, J., & Moro, M. R. (2016). Relations between Nonsuicidal

Self-Injury and Suicidal Behavior in Adolescence: A Systematic Review. PloS one, 11(4), e0153760. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0153760

Gratz, K. L.,

& Roemer, L. (2008). The relationship between emotion dysregulation and

deliberate self-harm among female undergraduate students at an urban commuter

university. Cognitive

behaviour therapy, 37(1),

14–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506070701819524

Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía

e Informática (2021, 8 de septiembre). Estadísticas a propósito del día mundial

para la prevención del suicidio. Datos nacionales (Comunicado de prensa). https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/saladeprensa/aproposito/2020/suicidios2020_Nal.pdf

Instituto Nacional de

Estadística, Geografía e Informática (2021, 27 de enero). Cracterísticas

de las defunciones registradas en México durante enero a agosto de 2020

(Comunicado de prensa). https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/saladeprensa/boletines/2021/EstSociodemo/DefuncionesRegistradas2020_Pnles.pdf

Jerónimo, M. A., Piñar, S., Samos, P., González, A. M., Bellsolá,

M., Sabaté, A., León, J., Aliart, X., Martín, L .M., Aceña, R., Pérez, V., & Córcoles,

D. (2021). Intentos e ideas de suicidio durante la pandemia por COVID-19 en

comparación con los años previos. Revista

de psiquiatría y salud mental, 573 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rpsm.2021.11.004

Joiner, T., Van, K., Witte, T., Selby, E., Ribeiro, J., Lewis, R. &

Rudd, D. (2009).Main Predictions of the

Interpersonal-Psychological Theory ofSuicidal

Behavior: Empirical Tests in Two Samples of Young Adults.Journal

Abnorm Psychol. 118(3), 634–646. Doi: 10.1037/

a0016500

Klonsky, E. D., & May, A. M. (2015). The Three-Step Theory (3ST): A

new theory of suicide rooted in the “ideation-to-action” framework. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy,

8(2), 114–129. https://doi.org/10.1521/ijct.2015.8.2.114

Klonsky, E. D., May, A. M., & Saffer,

B. Y. (2016). Suicide, Suicide Attempts, and Suicidal Ideation. Annual review of clinical psychology, 12, 307–330. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093204

Lai, K. (2021). Fit Difference Between Nonnested Models Given Categorical Data: Measures and

Estimation. Structural

Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 28(1), 99-120. https://

doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2020.1763802

Ma, J., Batterham, P. J., Calear, A. L., & Han, J. (2016). A systematic review of

the predictions of the Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of Suicidal Behavior. Clinical psychology review, 46, 34–45.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.04.008

Mars, B., Heron, J., Klonsky, E. D., Moran, P.,

O'Connor, R. C., Tilling, K., Wilkinson, P., & Gunnell, D. (2019). What

distinguishes adolescents with suicidal thoughts from those who have attempted

suicide? A population-based birth cohort study. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines, 60(1), 91–99. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12878

McAuliffe, C., Slemon, A., Goodyear, T.,

McGuinness, L., Shaffer, E., & Jenkins, E. K. (2022). Connectedness in the

time of COVID-19: Reddit as a source of support for

coping with suicidal thinking. SSM

Qualitative research in health 2, 1-9 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmqr.2022.100062

Melhem,

N. M., Porta, G., Oquendo, M. A., Zelazny, J., Keilp, J. G., Iyengar, S., Burke, A., Birmaher,

B., Stanley, B., Mann, J. J., & Brent, D. A. (2019). Severity and

Variability of Depression Symptoms Predicting Suicide Attempt in High-Risk

Individuals. JAMA psychiatry, 76(6), 603–613.

https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.4513

Navarrete, B. E. M., Herrera,

R. J., & León, P. P. (2019). Los límites de la prevención del suicidio. Revista de la asociación española de

neuropsiquiatría, 39(135), 193-214 https://dx.doi.org/10.4321/s0211-57352019000100011

O'Connor, R. C., & Kirtley,

O. J. (2018). The integrated motivational-volitional model of suicidal behaviour. Philosophical

transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences, 373(1754), 20170268.

https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2017.0268

Ordoñez-Carrasco, J. L., Salgueiro, M.,

Sayans-Jiménez, P., Blanc-Molina, A., García-Leiva, J. M., Calandre, E. P.,

& Rojas, A. J. (2018). Propiedades psicométricas de la versión en español

del Cuestionario de Necesidades Interpersonales de 12 ítems en pacientes con

síndrome de fibromialgia. Anales de

Psicología / Annals of Psychology, 34(2),

274–282. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.34.2.293101

Padrós,

F., & Pintor, S. B. E. (2021). Estructura interna y confiabilidad del BDI

(Beck Depression Inventory)

en universitarios de Michoacán (México).

Psicodebate, 21(1) 7-17. http://dx.doi.org/10.18682/pd.v21i1.2034

Posner, K., Brown, G. K., Stanley, B., Brent, D. A., Yershova, K. V., Oquendo, M. A., Currier, G. W., Melvin, G.

A., Greenhill, L., Shen, S., & Mann, J. J. (2011). The Columbia-Suicide

Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from

three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. The American journal of psychiatry, 168(12), 1266–1277. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111704

Reynoso, G. O. U., Caldera, M.

J. F., Carreño, P. B. V., García, O. D. P., & Velázquez, A. L. A. (2019).

Modelo explicativo y predictivo de la ideación suicida en una muestra de

bachilleres mexicanos. Psicología desde

el Caribe, 36(1), 82-100 ISSN 2011-7485.

Sandoval Ato, R., Vilela

Estrada, M. A., Mejia, C. R., & Caballero

Alvarado, J. (2018). Riesgo suicida asociado a bullying

y depresión en escolares de secundaria [Suicide risk associated with bullying and depression in high school]. Revista chilena de pediatria,

89(2), 208–215. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0370-41062018000200208

Schuler, K. R.,

Smith, P. N., Rufino, K. A., Stuart, G. L., & Wolford-Clevenger,

C. (2021). Examining the temporal stability of

suicide capability among undergraduates: A latent growth analysis. Journal of affective disorders, 282,

587–593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.12.169

Serra, M., Presicci, A., Quaranta, L., Caputo, E., Achille, M., Margari,

F., Croce, F., et al. (2022). Assessing Clinical Features of Adolescents

Suffering from Depression Who Engage in Non-Suicidal Self-Injury. Children, 9(2), 201 http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/children9020201

Sher L. (2020). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on

suicide rates. QJM : monthly journal of the Association of

Physicians, 113(10), 707–712. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcaa202

Solis, E. M., & Gómez-Peresmitré, G. (2020). Cuestionario

de riesgo de autolesión (CRA): propiedades psicométricas y resultados en una

muestra de adolescentes. Revista Digital Internacional de Psicología y

Ciencia Social, 6(1), 123-141. https://doi.org/10.22402/j.rdipycs.unam.6.1.2020.206.123-141

Solis,

E. M. (Noviembre 2021) Validez y confiabilidad de

la Escala de riesgo suicida de Plutchik [Sesión

de conferencia]. XXVIII Congreso Mexicano de Psicología y I Congreso

Latinoamericano de Psicología.

Toro, R., González, C.,

Mejía-Vélez, S., & Avendaño-Prieto, B. (2021). Modelo de riesgo suicida

transcultural: Evidencias de la capacidad predictiva en dos países de

Latinoamérica. Ansiedad y estrés, 27,

112-118 https://doi.org/10.5093/anyes2021a15

Trejo, C. V. H. (2018)

Adaptación, validación y sensibilidad de

las escalas de la teoría psicológica interpersonal del suicidio. Tesis

Universidad michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo. Enero. Posgrado en

psicología.

Valdez-Santiago, R., Marín-Mendoza, E., &

Torres-Falcón, M. (2021). Análisis comparativo del marco legal en salud mental

y suicidio en México. Salud Pública

De México, 63(4), 554-564. https://doi.org/10.21149/12310

Valdez-Santiago, R., Solórzano,

E. H., Iñiguez, M. M., Burgos, L. Á., Gómez Hernández, H., & Martínez

González, Á. (2018). Attempted suicide

among adolescents in Mexico: prevalence and associated factors at the national

level. Injury prevention

: journal of the International Society for Child and Adolescent Injury

Prevention, 24(4), 256–261.

https://doi.org/10.1136/injuryprev-2016-042197

Van Orden, K. A., Witte, T. K., Cukrowicz,

K. C., Braithwaite, S.R., Selby, E. A., & Joiner, T. EJr.

(2010). The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychological Review, 117, 575. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/a0018697

Vargas-Halabí, Tomás. (2016).

Cultura organizativa e innovación: un modelo explicativo (Tesis doctoral). Universidad de Valencia, España.

Watanabe, M., & Tanaka, H. (2022). Increased

suicide mortality in Japan during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Psychiatry research, 309, 114422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114422

Wilkinson, P., Kelvin, R., Roberts, C., Dubicka, B., & Goodyer, I. (2011). Clinical and

psychosocial predictors of suicide attempts and nonsuicidal

self-injury in the adolescent depression antidepressants and psychotherapy

trial (ADAPT). American Journal of Psychiatry, 168, 495-501. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10050718

Wolford-Clevenger, C., Stuart, G. L., Elledge, L. C., McNulty, J. K., & Spirito, A. (2020).

Proximal Correlates of Suicidal Ideation and Behaviors: A Test of the

Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of Suicide. Suicide & life-threatening behavior, 50(1), 249–262. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12585

Wolff, J., Thompson, E., Thomas, S., Nesi, J.,

Bettis, A., Ransford, B., . . . Liu, R. (2019). Emotion dysregulation and

non-suicidal self-injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Psychiatry, 59, 25-36. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2019.03.004

Zar, J.H. (2010).

Biostatistical Analysis. 5th ed. Pearson Prentice Hall, New Jersey.

Zeppegno, P., Calati, R., Madeddu, F., & Gramaglia, C.

(2021). The Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of Suicide to Explain Suicidal

Risk in Eating Disorders: A Mini-Review. Frontiers in psychiatry, 12, 690903. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.690903