http://dx.doi.org/10.24016/2022.v8.260

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

An explanatory model of suicidal ideation based on

family functionality and mental health problems: A cross-sectional study of

medical students

Un modelo explicativo de la ideación suicida basado en

la funcionalidad familiar y los problemas de salud mental: Un estudio

transversal de estudiantes de medicina

Leslie Aguilar-Sigueñas 1*, David

Villarreal-Zegarra 2

1 Universidad César Vallejo, Escuela de Medicina, Piura, Peru.

2 Instituto Peruano de Orientación Psicológica, Lima, Peru.

* Correspondence: Leslie Aguilar-Sigueñas. E-mail: leslieemilyaguilar@gmail.com.

Received: February 23, 2022. | Revised: November 01,

2022. | Accepted: December 15, 2022. | Published Online: December

15, 2022.

CITE IT AS:

Aguilar-Sigueñas, L., &

Villarreal-Zegarra, D. (2022). An explanatory model of suicidal ideation based

on family functionality and mental health problems: A cross-sectional study of

medical students. Interacciones, 8,

e260. http://dx.doi.org/10.24016/2022.v8.260

ABSTRACT

Background: One of the mental health problems with the greatest

impact on people’s lives is suicidal behavior, a largely preventable public

health problem that accounts for almost half of all violent deaths. The

aim of the study is to propose a model that can explain and predict suicidal

ideation based on mental health problems (stress-anxiety-depression) and family

functionality (cohesion, flexibility, and cohesion). Methods: Our study

is cross-sectional. The population consisted of medical students from all over

Peru. Non-probability sampling was used. We used Family Cohesion and

Adaptability Evaluation Scale (FACES-III), Family Communication Scale, Family

Satisfaction Scale, Depression Anxiety and Stress Scales (DASS-21), and the

Scale for Suicide Ideation – Worst (SSI-W). Results: A total of 480

participants were included. The prevalence of suicidal ideation was 39%.

Poisson regression analysis adjusted identified that people with anxiety

symptoms were more than four times more likely to have suicidal ideation

(PR=4.89; 95% CI:1.90-12.64). Also, people with moderate to high levels of

family communication were much less likely to have suicidal ideation (PR= 0.07;

95% CI: 0.01-0.41), making it a protective factor. The proposed model presented

optimal goodness-of-fit indices (CFI=0.974; TLI=0.974; SRMR=0.055;

RMSEA=0.062). In addition, the proposed model can explain the presence of

suicidal ideation in 88.3% (R2=0.883). Conclusions: Our model

can explain 88.3% of suicidal behavior based on family relationships and mental

health problems in medical students. In addition, the variables that alone were

most associated with suicidal behavior were anxious symptoms and family

communication as risk factors and protective factors, respectively.

Keywords: suicidal ideation, depression, anxiety, family,

stress.

RESUMEN

Antecedentes: Uno de

los problemas de salud mental mayor impacto en la vida de las personas, es la

conducta suicida, que constituye un problema de salud pública en gran medida

prevenible, siendo responsable de casi la mitad de todas las muertes violentas.

Nuestro estudio es proponer un modelo que permita explicar y predecir la

ideación suicida a partir de los problemas de salud mental

(estrés-ansiedad-depresión) y la funcionalidad familiar (cohesión, flexibilidad

y cohesión). Método: Nuestro estudio es transversal. La población estuvo

constituida por médicos internos de todo el Perú. Se utilizó un muestreo no

probabilístico. Se utilizó la Escala de Evaluación de la Cohesión y

Adaptabilidad Familiar (FACES-III), la Escala de Comunicación Familiar, la

Escala de Satisfacción Familiar, Escala de Depresión, Ansiedad y Estrés

(DASS-21) y la Escala de Ideación Suicida - Peor (SSI-W). Resultados: Se

incluyó a un total de 480 participantes. La prevalencia de ideación suicida fue

del 39%. El análisis de regresión de Poisson ajustado identificó que las

personas con síntomas de ansiedad tenían más de cuatro veces más probabilidades

de tener ideación suicida (PR=4.89; IC95%:1.90-12.64). Asimismo, las personas

con niveles de comunicación familiar de moderados a altos eran mucho menos

propensas a tener ideación suicida (PR=0.07; IC95%: 0.01-0.41), lo que lo

convierte en un factor protector. El modelo propuesto presentó óptimos índices

de bondad de ajuste (CFI=0.974; TLI=0.974; SRMR=0.055; RMSEA=0.062). Además, el

modelo propuesto puede explicar la presencia de ideación suicida en un 88,3% (R2=0.883).

Conclusiones: Nuestro modelo puede explicar una gran proporción de las

conductas suicidas basadas en las relaciones familiares y los problemas de

salud mental en médicos internos. Además, las variables que por sí solas se

asociaron más con la conducta suicida fueron los síntomas ansiosos y la

comunicación familiar como factores de riesgo y de protección, respectivamente.

Palabras clave: ideación suicida, depresión, ansiedad, familia,

estrés.

BACKGROUND

As of January 2023, more than 661 million people with

a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 and more than 6 million deaths have been

reported to the World Health Organization (WHO) (World Health Organization,

2023). The context of the pandemic has led to the redeployment of health

personnel and materials to focus on COVID-19 areas, the overload of care, the

high risk that health personnel has of becoming

infected with this virus, the shortage of adequate personal protective

equipment, long working hours, and the fear of infecting their families have

all affected the physical and mental health of health personnel (Della Monica

et al., 2022; Huarcaya-Victoria, 2020). A

particularly at-risk group is medical internship students who were exposed to

the clinical context but are more prone to mental health problems because of

their student status (Jacob et al., 2020).

Worldwide, suicides comprise 50% and 71% of reported

violent deaths for males and females, respectively (World Health Organization,

2014). In 2019, the WHO found that each year, approximately 800,000 people

commit suicide, and countless more attempt suicide (World Health Organization,

2021). In 2017, it was the second leading cause of death among university

students (Santos et al., 2017). In some countries, reported suicides are

highest among young people, ranking second worldwide as the leading cause of death

among 15-29-year-olds in 2019

(World Health Organization, 2021). In particular, in Peru,

between 2017 to 2021, the highest incidence of suicide was among people aged 20

to 29 years old (26.2%) and was more frequent in men (69.5%) (Contreras-Cordova

et al., 2022). In addition, between 2004 and 2013, the suicide rate in Peru

increased from 0.46 (CI95%: 0.38-0.55) to 1.13 (CI95%: 1.01-1.25) per 100,000

inhabitants in those years, respectively (Hernández-Vásquez et al., 2016).

One of the many mental health problems today, and

considered one of the most severe because of its likely impact on people’s

lives, is suicidal behavior, which is a largely preventable public health

problem, accounting for almost half of all violent deaths. Suicidal behaviors

present three main clinical manifestations: suicidal ideation, attempted

suicide, and completed suicide (Denis-Rodríguez et al., 2017). Suicidal

ideation is the first of the suicidal behaviors to appear and is one of the

most significant risk signs for suicide prevention (Denis-Rodríguez et al.,

2017). The causation of suicidal ideation is multifactorial. Several studies

have concluded that negative life and mental health events such as

hopelessness, depressive symptomatology, stress, and anxiety are the most common

causes of suicidal ideation (Mortier et al., 2018). Also, social factors such

as those related to family conflicts, academia, and economic factors (Perales

et al., 2019), are the most important predictors for triggering this thinking

type in young university students.

Two main groups of theoretical models attempt to

explain suicidal ideation. On the one hand, those who consider suicidal

ideation to be an individual entity, see it as a clinical manifestation of a

major depressive disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). On the

other hand, trans-diagnostic models consider its origin as part of a continuum

of emotional distress that can develop into mental health problems

(stress-anxiety-depression) (González Pando et al., 2018), Thus, emotionally charged

events such as a pandemic may trigger onset of suicidal ideation. However, both

types of theoretical models consider that social factors and family support

networks play a considerable role in the emergence of these mental health

disorders.

One of the theoretical models that explain family

relationships is Olson’s circumplex model of couple and family systems (Olson

et al., 2019). The circumplex model proposes three dimensions. First, family

cohesion is the relationship between family members. Second, family flexibility

is the ability of the family system to adapt to change and establish norms. In

addition, both dimensions are curvilinear, meaning that very high or low levels

are dysfunctional, and the medium level is functional (Olson et al., 2019).

Third, family communication is the ability of the family system to transmit

information, feelings, and needs between members (Olson et al., 2019). Also, a

facilitating dimension influences the others dimensions. These three variables

together comprise family functionality.

Our study seeks to link both theoretical models

(trans-diagnostic model and circumplex model of the couple and family systems)

to predict the occurrence of suicidal ideation in Peruvian medical students.

Therefore, the general aim of the study is to propose a model that can explain

and predict suicidal ideation based on mental health problems

(stress-anxiety-depression) and family functionality (cohesion, flexibility,

and cohesion).

METHODS

Study design

Our study is cross-sectional.

Setting

During data collection, Peru was facing the third

wave. Although mortality was not as high as in the previous two waves, there

was a rapid increase in the number of confirmed cases due to the new variant

known as omicron, which was more contagious but less lethal. The increase in

confirmed cases generated fear and concern among health personnel, including

medical students, who were no strangers to infection.

Participants

The population consisted of medical students from all

over Peru. The inclusion criteria were that they were over 18 years of age,

agreed to participate in the virtual questionnaire by giving their informed

consent, and were doing their internship in a health center. We excluded

participants who reported receiving antidepressant treatment, those with a

disorder diagnosis, and those who did not complete the questionnaire.

Non-probability sampling was used. A minimum sample

size of 400 participants was calculated since simulation studies have

identified that with at least 400 participants, there would be no significant

changes in the goodness-of-fit indices in the models evaluated when using

structural equation modeling (Iacobucci, 2010).

Variables and instruments

Mental health problems

The DASS-21 has twenty-one Likert-type items with four

response options (0-3 points) and evaluates the symptomatology that

participants have perceived in the last week. The DASS-21 has three dimensions,

the depressive symptoms dimension (items 3, 5, 10, 13, 16, 17, and 21), anxious

symptoms (items 2, 4, 7, 9, 15, 19, and 20), and stress (items 1, 6, 8, 11, 12,

14 and 18) (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995). A previous study reported optimal

internal consistency values for depressive symptoms (α=0.85), anxious symptoms

(α=0.72), and stress (α=0.79) (Román Mella et al.,

2014). Our prevalence assessment study dichotomized scores for depressive

symptoms (≥14), anxious symptoms (≥10), and stress (≥19) (Lovibond &

Lovibond, 1995).

Family functionality

Family cohesion and adaptability: The Family Cohesion

and Adaptability Evaluation Scale (FACES-III) was applied, with 20 items, with

5-choice Likert-type responses, the odd items are adaptability items, and the

even items are cohesion items (Olson, 1986). The FACES-II has shown evidence of

validity and reliability in Peruvian youth (Bazo-Alvarez

et al., 2016). Our study dichotomized cohesion and adaptability scores. We

considered functionality values for cohesion in the 35 to 45 score range

(separate-connected) and functionality values for adaptability in the 20 to 28

score range (structured-flexible) (Olson, 1986).

Family communication: The Family Communication Scale

(FCS), with 10 Likert-type items with five response options ranging from

strongly disagree to strongly agree (Olson et al., 2019). The FCS has evidence

of validity and reliability (ω>0.80) in the Peruvian context and shows

evidence of factorial independence between men and women (Copez-Lonzoy

et al., 2016). Family communication was considered a linear variable, so scores

≥36 were dichotomized as medium-high (Valle & Cabrera, 2020).

Family satisfaction: The Family Satisfaction Scale

(FSS) consists of ten Likert-type items with five response options ranging from

extremely dissatisfied to extremely satisfied (Olson et al., 2019). In the

Peruvian context, the FSS has evidence of internal structure validity, internal

consistency (ω= 0.925), and gender invariance (Villarreal-Zegarra et al.,

2017). Family satisfaction was considered a linear variable, so scores ≥36 were

dichotomized as medium-high (Valle & Cabrera, 2020).

Suicidal ideation

The Scale for Suicide Ideation – Worst (SSI-W) is a

19-item instrument, with each item having three response options (0 to 2

points), which suggest an increasing level of risk, seriousness, and intensity

of suicidal behavior (Beck et al., 1979). BIS has optimal reliability values in

the overall dimension (α=0.79) (Eugenio Torres & Zelada

Alcántara, 2011) and has been used in studies in the

Peruvian context (Chavez-Cáceres et al., 2020). We

dichotomized the presence of suicidal ideation based on scores ≥14 (Beck et

al., 1999).

Covariates

Our study collects socio-demographic information on

gender (male and female), age group, and with whom they live (live alone or

with at least one family member).

Procedures

The survey link was disseminated through e-mails and

social networks at the national level with the help of the delegates of the

different universities with medical degrees. The time given for its resolution

was two weeks, from 5 to 19 November 2021.

Statistical methods

Correlation analysis

Spearman’s correlation coefficient between variables

was used since it does not require a normal distribution. Cut-offs were

proposed for small (rs > 0.20),

moderate (rs > 0.50), and large (rs > 0.80) effects (Ferguson,

2009).

Regression analysis

We assessed the association of the outcome (suicidal ideation)

with exposure, such as the sociodemographic variables, mental health problems

(anxiety, stress, and depression), and family functionality (family cohesion,

flexibility, and communication). The crude and adjusted prevalence ratio (PR)

was used as a measure of association. The analyses were estimated using

generalized linear models with robust variance estimates, assuming a Poisson

distribution with log link functions (Beran & Violato, 2010).

Structural equation modeling (SEM)

SEM was used with the outcome and exposure variables.

We used the weighted least square mean and variance adjusted (WLSMV) estimator

(Suh, 2015). Also, we used the polychoric correlation matrix (Dominguez-Lara,

2014). The SEM was evaluated in two steps. First, evaluated different

goodness-of-fit indices: Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation (RMSEA),

standardized root mean square (SRMR), comparative fit index (CFI), and Tucker

Lewis index (TLI). The cut-off points of CFI and TLI>0.95; and RMSEA and

SRMR <0.08 were considered (Xia & Yang, 2018). The second step was to

assess the amount of variance explained by perceived stress (output variables)

by the coefficient of determination (R2).

The analyses were performed R Studio, with the

packages “lavaan”, “semTools”,

and “semPlot”.

Ethical aspects

The study

protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Universidad César Vallejo.

In addition, the ethical norms established in the Declaration of Helsinki were

respected and the participants were asked to sign a virtual informed consent

form.

RESULTS

Participants

A total of 501 Peruvian medical inmates were

evaluated, of whom 480 met the inclusion criteria and were included in the

study. Within the group of excluded inmates, it was identified that they

self-reported having a diagnosis of a mental health problem (n=15), were taking

antidepressants (n=2), or did not agree to participate in the study (n=4).

Among the participants included in the study, the

majority were male (56.7%; n=272), the most frequent age group was between 18

and 25 years old (79.8%; n=383), and the majority lived with at least one

family member (64.0%; n=307). The prevalence of suicidal ideation was estimated

at 39% (n=187). In addition, table 1 shows the prevalence of mental health

problems.

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of participants

(n=480).

|

|

|

n |

% |

|

Sex |

Men |

272 |

56.7% |

|

|

Women |

208 |

43.3% |

|

Age

group |

18 to 25 |

383 |

79.8% |

|

|

26 to 30

|

45 |

9.4% |

|

|

31 to 35

|

21 |

4.4% |

|

|

36 to

more |

27 |

5.6% |

|

|

No

report |

4 |

0.8% |

|

Live

with… |

Lives

with at least one member of your family |

307 |

64.0% |

|

|

Lives

alone |

173 |

36.0% |

|

Depression |

No |

293 |

61.0% |

|

|

Yes |

187 |

39.0% |

|

Anxiety |

No |

282 |

58.8% |

|

|

Yes |

198 |

41.3% |

|

Stress |

No |

365 |

76.0% |

|

|

Yes |

115 |

24.0% |

|

Family

cohesion |

Dysfunctionality |

338 |

70.4% |

|

|

Functionality |

142 |

29.6% |

|

Family

adaptability |

Dysfunctionality |

382 |

79.6% |

|

|

Functionality |

98 |

20.4% |

|

Family

satisfaction |

Low |

277 |

57.7% |

|

|

Medium-High |

203 |

42.3% |

|

Family

communication |

Low |

268 |

55.8% |

|

|

Medium-High |

212 |

44.2% |

|

Suicidal

ideation |

No |

293 |

61.0% |

|

|

Yes |

187 |

39.0% |

Correlation analysis

Our study found a moderate relationship between family

functioning variables and mental health problems (rs>0.70).

In addition, our study found that both family functioning and mental health

problems variables correlated moderately strongly with suicidal ideation in

medical students (rs>0.70).

Table 2 shows the correlation between the mental health problems variables and

the correlation between the family functioning variables.

Table 2. Correlation coefficients between variables of interest

(n=480).

|

|

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

(6) |

(7) |

(8) |

|

1.

Depressive symptoms |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2.

Anxious symptoms |

0.956 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3.

Stress |

0.966 |

0.962 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

4.

Family cohesion |

-0.748 |

-0.757 |

-0.764 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

5.

Family adaptability |

-0.729 |

-0.726 |

-0.753 |

0.962 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

6.

Family satisfaction |

-0.755 |

-0.761 |

-0.759 |

0.822 |

0.784 |

1 |

|

|

|

7.

Family communication |

-0.766 |

-0.765 |

-0.769 |

0.819 |

0.786 |

0.916 |

1 |

|

|

8.

Suicidal ideation |

0.742 |

0.743 |

0.748 |

-0.747 |

-0.742 |

-0.738 |

-0.754 |

1 |

Note: All values reported significant values

(p<0.001).

Regression analysis

Poisson regression analysis identified that people

with anxiety symptoms were more than four times more likely to have suicidal

ideation (PR=4.89; 95% CI:1.90 - 12.64). On the other hand, people with

moderate to high levels of family communication were much less likely to have

suicidal ideation (PR= 0.07; 95% CI: 0.01 - 0.41), making it a protective

factor (see Table 3).

Table 3. Raw and adjusted prevalence ratio (PR) for suicidal ideation

(n=480).

|

|

|

rPR |

p |

aPR |

p |

|

Sex |

Men |

1 |

|

1 |

|

|

|

Women |

0.96

[0.72 - 1.28] |

0.764 |

0.97

[0.73 - 1.31] |

0.862 |

|

Live

with… |

Lives

with at least one member of your family |

1 |

|

1 |

|

|

|

Lives

alone |

3.25

[2.41 - 4.39] |

0.000 |

1.18

[0.82 - 1.71] |

0.374 |

|

Depression |

No |

1 |

|

1 |

|

|

|

Yes |

13.08

[8.23 - 20.80] |

0.000 |

0.95

[0.42 - 2.18] |

0.908 |

|

Anxiety |

No |

1 |

|

1 |

|

|

|

Yes |

19.06

[10.85 - 33.49] |

0.000 |

4.89 [1.90 - 12.64] |

0.001 |

|

Stress |

No |

1 |

|

1 |

|

|

|

Yes |

4.74

[3.54 - 6.35] |

0.000 |

1.31

[0.84 - 2.04] |

0.234 |

|

Family cohesion |

Dysfunctionality |

1 |

|

1 |

|

|

|

Functionality |

0.07

[0.03 - 0.16] |

0.000 |

0.77

[0.27 - 2.19] |

0.622 |

|

Family

adaptability |

Dysfunctionality |

1 |

|

1 |

|

|

|

Functionality |

1.35

[0.97 - 1.87] |

0.076 |

1.36

[0.87 - 2.13] |

0.180 |

|

Family

satisfaction |

Low |

1 |

|

1 |

|

|

|

Medium-High |

0.03

[0.01 - 0.08] |

0.000 |

0.97

[0.24 - 3.96] |

0.967 |

|

Family

communication |

Low |

1 |

|

1 |

|

|

|

Medium-High |

0.03

[0.01 - 0.08] |

0.000 |

0.07 [0.01 - 0.41] |

0.003 |

Note: rPR = raw prevalence

ratio. aPR = adjusted prevalence ratio. Model

adjusted by sex, live with other people, depression, anxiety, stress, family

cohesion, family adaptability, family communication, and family satisfaction.

The outcome was suicidal ideation. Values in bold were significant (p<0.05).

Structural equation modeling

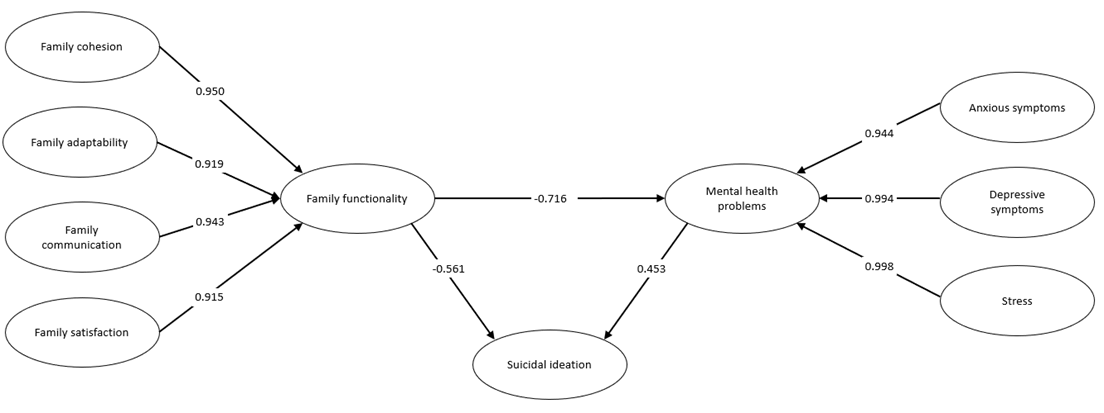

Our study presented a model that predicts suicidal

ideation based on family functionality and mental health problems. Our model

proposes that family functioning influences mental health problems because we

found a moderate relationship between the two variables. The proposed model

(see Figure 1) presented optimal goodness-of-fit indices (X2=7364.1;

df=3070; CFI=0.974; TLI=0.974; SRMR=0.055;

RMSEA [90% CI]= 0.062 [0.060 - 0.064]). In addition,

the proposed model can explain the presence of suicidal ideation in 88.3% (R2=0.883).

Our model finds a negative influence of family

functioning on the presence of mental health problems (β=-0.716). In other

words, the higher the family functioning score, the lower the scores for mental

health problems. Furthermore, family functioning has the most influence on the

presence of suicidal ideation (β=-0.561) than mental health problems (β=0.453).

Figure 1. SEM of suicidal ideation, family functionality, and

mental health problems (n=480).

Note: All variables presented are latent, observable

variables (items) are not shown.

DISCUSSION

Main finding and interpretation

Our conclusions propose that the dimensions of the

circumplex model and the mental health problems largely explain suicidal

ideation. Mainly, the most important predictors of suicidal ideation in medical

students are family communication and anxious symptoms. Our study proposes that

family relationships have the most influence on the presence of suicidal

ideation than mental health problems themselves. Based on the circumplex model

theory, balanced families have more functional members with higher well-being

(i.e., less suicidal ideation) than unbalanced families (i.e., low

communication and family satisfaction) (Olson et al., 2019). Therefore, our

study supports this hypothesis of the circumplex model.

Our model also highlights the role of family

relationships in the presence of mental health problems. Therefore, it is of

utmost importance to be able to include family variables in epidemiological

models of mental health problems.

Comparison with other studies

We found other studies that propose explanatory models

using a different variable set. However, they manage to explain a smaller

proportion of suicidal ideation. One study assessed possible mediated variables

for suicidal risk in college students. The study found that impulsivity, family

history of mental disorder and suicide attempt, and history of suicide attempts

in the past year were mediators of suicidal risk (Gómez Tabares

et al., 2019). However, their model only explained 62.7% of suicidal risk.

Another study on adolescents found that family violence and support influence

depressive symptoms and suicidal behavior with peers, and this in turn

influences suicidal ideation (Ramírez & Oduber, 2015). However, the model

is only able to explain 39% of suicidal ideation. Another study on Chinese

university students includes variables such as bullying, internet addiction,

and childhood trauma to explain suicidal ideation (Lu et al., 2020). While this

study achieves adequate goodness-of-fit indices, it does not report how much

the model can explain suicidal ideation. There is heterogeneity in the

variables and methodologies used to propose models to explain suicidal ideation

in medical students. However, we have not found a model that manages to explain

suicidal ideation in such a high percentage as the model we propose.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have found

several factors associated with suicidal ideation, such as being female,

alcohol use, having depression, being a junior or pre-clinical student,

exposure to COVID-19, academic stress, history of psychiatric or physical disorders,

financial problems, fear of educational deterioration, online learning

problems, fear of infection, loneliness, low physical activity, low social

support, problematic internet or smartphone use, and young age (Kaggwa et al.,

2023; Peng et al., 2023). In contrast to these findings, our study found that

when adjusting for different variables, anxious symptoms and family

communication are the main risks and protective factors, respectively. Our

results could be explained by the fact that the ability to communicate one’s

emotions and needs within the family could be a protective factor for a college

student to have suicidal thoughts.

As for the prevalence of suicidal ideation,

meta-analyses place it well below the findings of our study. The meta-analyses

report it at 18.7% (95% CI: 14.1%-23.3) (Kaggwa et al., 2023), 15 % (95 % CI,

11 %-18 %) (Peng et al., 2023), and 11.1% (95% CI, 9.0% to 13.7%) (Rotenstein et al., 2016).

Therefore, the sample assessed may have a high prevalence of suicidal

ideation compared to that reported by other studies. One possible explanation

for the potential increase in suicidal ideation is the context of COVID-19,

which generated an increase in the prevalence of mental health problems (Meda et al., 2021).

Public health implications

The findings of our study could be used to guide the

formulation of policies and programs to address suicidal behavior in medical

students. Interventions could be implemented to improve family communication

and address anxiety symptoms in medical students, to reduce mental health

problems (Fulgoni et al., 2019). In addition, the high level of suicidal

ideation found in medical students suggests the need for preventive

interventions to address this public health problem. This could include

workplace suicide prevention programs and emotional support programs for

medical students (Joshi et al., 2015; Skaczkowski et

al., 2022; Witt et al., 2019).

Limitations and strengths

We have identified three limitations in our study.

First, our study is cross-sectional. Therefore, causal relationships should not

be assumed. Secondly, our study may have errors in the measurement of outcome

or exposure factors. Although we use validated psychometric instruments, this

is not a substitute for a gold standard such as a clinical interview with a

mental health professional. Third, our study is not probabilistic. Four, other

variables that could potentially better explain suicidal ideation, such as

family violence, history of suicide attempts, or self-harming behavior, were

not included. Fourth, it was not possible to perform a mediation or moderation

analysis because the assumptions of the analysis were not met. Therefore, the

results are not representative of all medical interns in Peru. On the other

hand, the main strength of our study is that it includes many variables to

explain the full spectrum of family relationships and the most frequent mental

health problems.

Conclusions

Our model can explain 88.3% of suicidal behavior based

on family relationships and mental health problems in medical interns. In

addition, the variables that alone were most associated with suicidal behavior

were anxious symptoms and family communication as risk factors and protective

factors, respectively. Also, we found a high prevalence of suicidal ideation

(39%) in medical interns. Our study suggests that family relationships

influence suicidal ideation, so interventions based on improving family

relationships could reduce suicidal ideation in Peruvian medical interns.

ORCID

Leslie Aguilar-Sigueñas https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6677-5904

David Villarreal-Zegarra https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2222-4764

CONTRIBUTION OF THE AUTHORS

Leslie Aguilar-Sigueñas:

Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing -

Original Draft, Visualization.

David Villarreal-Zegarra: Conceptualization,

Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Writing - Review & Editing,

Supervision.

FUNDING

Our study was self-funded.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

DVZ is editor of Interacciones.

The study is part of an LAS graduate thesis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REVIEW PROCESS

This study has been reviewed by external peers in a

double-blind mode. The editor in charge Renzo Rivera.

The review process can be found as supplementary material 1.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are

openly available in supplementary material 2.

DISCLAIMER

The authors are responsible for all statements made in

this article.

REFERENCES

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Guía de consulta de los criterios

diagnósticos del DSM 5. Asociación Americana de Psiquiatría; Arlington, VA.

Bazo-Alvarez, J. C., Bazo-Alvarez, O. A., Aguila, J.,

Peralta, F., Mormontoy, W., & Bennett, I. M.

(2016). Propiedades psicométricas de la escala de funcionalidad familiar

FACES-III: un estudio en adolescentes peruanos. Revista peruana de medicina

experimental y salud publica, 33(3),

462–470. https://doi.org/10.17843/rpmesp.2016.333.2299

Beck, A. T., Brown, G. K., Steer, R. A., Dahlsgaard, K. K., & Grisham, J. R. (1999). Suicide

ideation at its worst point: a predictor of eventual suicide in psychiatric

outpatients. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 29(1), 1–9.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10322616

Beck, A. T., Kovacs, M., & Weissman, A. (1979).

Assessment of suicidal intention: the Scale for Suicide Ideation. Journal of

Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 47(2), 343–352.

https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-006x.47.2.343

Beran, T. N.,

& Violato, C. (2010). Structural equation modeling in medical research: a

primer. BMC Research Notes, 3, 267.

https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-3-267

Chavez-Cáceres, R.,

Luna-Muñoz, C., Mendoza-Cernaqué, S., Ubillus, J. J., & Lopez, L. C. (2020). Factors

associated with suicide ideation in patients of a Peruvian Hospital. Revista de la Facultad de Medicina Humana, 20(3), 1–1. https://doi.org/10.25176/RFMH.v20i3.3054

Contreras-Cordova, C. R., Atencio-Paulino, J. I., Sedano, C., Ccoicca-Hinojosa,

F. J., & Huaman, W. P. (2022). Suicidios en el

Perú: Descripción epidemiológica a través del Sistema Informático Nacional de

Defunciones (SINADEF) en el periodo 2017-2021. Revista de neuro-psiquiatria, 85(1), 19–28.

https://doi.org/10.20453/rnp.v85i1.4152

Copez-Lonzoy, A. J.

E., Villarreal-Zegarra, D., & Paz-Jesús, Á. (2016). Propiedades

psicométricas de la Escala de Comunicación Familiar en estudiantes universitarios.

Revista Costarricense de Psicología, 35(1), 31–46.

https://doi.org/10.22544/rcps.v35i01.03

Della Monica, A., Ferrara,

P., Dal Mas, F., Cobianchi,

L., Scannapieco, F., & F Ruta, F. R. (2022). The impact of Covid-19 healthcare emergency on the

psychological well-being of health professionals: a review of literature. Annali Di Igiene: Medicina

Preventiva E Di Comunita, 34(1), 34.

https://doi.org/10.7416/ai.2021.2445

Denis-Rodríguez, E., Alarcón, M. E. B.,

Delgadillo-Castillo, R., Denis-Rodríguez, P. B., & Melo-Santiesteban, G.

(2017). Prevalence of Suicidal Ideation in Medical

Students of Latin America: a Meta-analysis. RIDE Revista Iberoamericana Para La Investigación Y El

Desarrollo Educativo, 8(15), 387–418.

https://doi.org/10.23913/ride.v8i15.304

Dominguez-Lara, S.

(2014). ¿Matrices Policóricas/Tetracóricas

o Matrices Pearson? Un estudio metodológico. Revista Argentina de Ciencias

Del Comportamiento, 6(1), 39–48.

https://doi.org/10.32348/1852.4206.v6.n1.6357

Eugenio Torres, S. R., & Zelada Alcántara, M. B.

(2011). Relación entre estilos de afrontamiento e ideación suicida en

pacientes viviendo con VIH del GAM “Somos Vida” del hospital nacional Sergio E.

Bernales de la ciudad de Lima (M. E. Dorival

Sihuas (ed.)) [Licenciatura en Psicología , Universidad

Señor de Sipán]. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12802/1600

Ferguson, C. J. (2009). An effect size primer: A guide

for clinicians and researchers. Professional Psychology: Research and

Practice, 40(5), 532–538. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015808

Fulgoni, C. M. F., Melvin, G. A., Jorm,

A. F., Lawrence, K. A., & Yap, M. B. H. (2019). The Therapist-assisted

Online Parenting Strategies (TOPS) program for parents of adolescents with

clinical anxiety or depression: Development and feasibility pilot. Internet Interventions, 18, 100285.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2019.100285

Gómez Tabares, A. S., Núñez, C., Caballo, V. E.,

Agudelo Osorio, M. P., Aguirre, G., & Mauricio, A. (2019). Predictores

psicológicos del riesgo suicida en estudiantes universitarios. Behavioral Psychology /

Psicología Conductual, 27(3), 391–413.

González Pando, D., Cernuda Martínez, J. A., Alonso

Pérez, F., Beltrán García, P., & Aparicio Basauri, V. (2018). Transdiagnóstico: origen e implicaciones en los cuidados de

salud mental. Revista de La Asociación Española de Neuropsiquiatría, 38(133),

145–166. https://doi.org/10.4321/s0211-57352018000100008

Hernández-Vásquez, A., Azañedo,

D., Rubilar-González, J., Huarez, B., & Grendas, L. (2016). Evolución y diferencias regionales de

la mortalidad por suicidios en el Perú, 2004-2013. Revista Peruana de

Medicina Experimental Y Salud Pública, 33(4), 751–757.

https://doi.org/10.17843/rpmesp.2016.334.2562

Huarcaya-Victoria, J. (2020). Consideraciones sobre la

salud mental en la pandemia de COVID-19. Revista Peruana de Medicina

Experimental Y Salud Pública, 37(2), 327–334.

https://doi.org/10.17843/rpmesp.2020.372.5419

Iacobucci, D. (2010). Structural equations modeling: Fit

Indices, sample size, and advanced topics. Journal of Consumer Psychology,

20(1), 90–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2009.09.003

Jacob, R., Li, T.-Y., Martin, Z., Burren, A., Watson,

P., Kant, R., Davies, R., & Wood, D. F. (2020). Taking care of our future

doctors: a service evaluation of a medical student mental health service. BMC

Medical Education, 20(1), 1–11.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02075-8

Joshi, S. V., Hartley, S. N., Kessler, M., & Barstead, M. (2015). School-based suicide prevention:

content, process, and the role of trusted adults and peers. Child and

Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 24(2), 353–370.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2014.12.003

Kaggwa, M. M., Najjuka, S.

M., Favina, A., Griffiths, M. D., & Mamun, M. A.

(2023). Suicidal behaviors and associated factors among medical students in

Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective

Disorders Reports, 11, 100456.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadr.2022.100456

Lovibond, S. H., & Lovibond, P. F. (1995). Manual

for the depression anxiety stress scales. Psychology Foundation of

Australia; Sydney, Australia. https://doi.org/10.1037/t01004-000

Lu, L., Jian, S., Dong, M., Gao, J., Zhang, T., Chen,

X., Zhang, Y., Shen, H., Chen, H., Gai, X., & Liu, S. (2020). Childhood

trauma and suicidal ideation among Chinese university students: the mediating

effect of Internet addiction and school bullying victimisation.

Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 29, e152.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796020000682

Meda, N., Pardini, S., Slongo,

I., Bodini, L., Zordan, M.

A., Rigobello, P., Visioli,

F., & Novara, C. (2021). Students’ mental health problems before, during,

and after COVID-19 lockdown in Italy. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 134,

69–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.12.045

Mortier, P., Auerbach, R. P., Alonso, J., Bantjes, J., Benjet, C., Cuijpers, P., Ebert, D. D., Green, J. G., Hasking, P., Nock, M. K., O’Neill, S., Pinder-Amaker, S., Sampson, N. A., Vilagut,

G., Zaslavsky, A. M., Bruffaerts,

R., Kessler, R. C., & WHO WMH-ICS Collaborators. (2018). Suicidal Thoughts

and Behaviors Among First-Year College Students: Results From the WMH-ICS

Project. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry,

57(4), 263–273.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2018.01.018

Olson, D. H. (1986). Circumplex Model VII: validation

studies and FACES III. Family Process, 25(3), 337–351.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.1986.00337.x

Olson, D. H., Waldvogel, L.,

& Schlieff, M. (2019). Circumplex Model of

Marital and Family Systems: An Update. Journal of Family Theory & Review,

11(2), 199–211. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12331

Peng, P., Hao, Y., Liu, Y., Chen, S., Wang, Y., Yang,

Q., Wang, X., Li, M., Wang, Y., He, L., Wang, Q., Ma, Y., He, H., Zhou, Y., Wu,

Q., & Liu, T. (2023). The prevalence and risk factors of mental problems in

medical students during COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 321, 167–181.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.10.040

Perales, A., Sánchez, E., Barahona, L., Oliveros, M.,

Bravo, E., Aguilar, W., Ocampo, J. C., Pinto, M., Orellana, I., & Padilla,

A. (2019). Prevalencia y factores asociados a

conducta suicida en estudiantes de la Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos,

Lima-Perú. Anales de La Facultad de Medicina, 80(1), 28–33.

https://doi.org/10.15381/anales.v80i1.15865

Ramírez, J. A. R., & Oduber, J. A. (2015). Ideación suicida y grupo de iguales: análisis en una

muestra de adolescentes venezolanos. Universitas

Psychologica, 14(3).

https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.upsy14-3.isgi

Román Mella, F., Vinet, E. V., & Alarcón Muñoz, A.

M. (2014). Escalas de Depresión, Ansiedad y Estrés (DASS-21): Adaptación y

propiedades psicométricas en estudiantes secundarios de temuco.

Revista Argentina de Clínica Psicológica, 23(2), 179–190.

Rotenstein, L. S.,

Ramos, M. A., Torre, M., Segal, J. B., Peluso, M. J.,

Guille, C., Sen, S., & Mata, D. A. (2016). Prevalence of Depression, Depressive Symptoms, and

Suicidal Ideation Among Medical Students: A Systematic Review and

Meta-Analysis. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 316(21),

2214–2236. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.17324

Santos, H. G. B. dos, dos Santos, H. G. B., Marcon, S. R., Espinosa, M. M., Baptista, M. N., & de

Paulo, P. M. C. (2017). Factors

associated with suicidal ideation among university students. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem,

25, e2878. https://doi.org/10.1590/1518-8345.1592.2878

Skaczkowski, G., van der Kruk, S., Loxton, S., Hughes-Barton, D.,

Howell, C., Turnbull, D., Jensen, N., Smout, M.,

& Gunn, K. (2022). Web-Based Interventions to Help Australian Adults

Address Depression, Anxiety, Suicidal Ideation, and General Mental Well-being:

Scoping Review. JMIR Mental Health, 9(2), e31018.

https://doi.org/10.2196/31018

Suh, Y. (2015). The Performance of Maximum Likelihood

and Weighted Least Square Mean and Variance Adjusted Estimators in Testing

Differential Item Functioning With Nonnormal Trait

Distributions. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal,

22(4), 568–580. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2014.937669

Valle, W., & Cabrera, M. (2020). Valores normativos de las escalas de satisfacción y

comunicación familiar: Un estudio preliminar. Teoría y Práctica: Revista Peruana de Psicología, 1(1), e23.

Villarreal-Zegarra, D., Copez-Lonzoy,

A., Paz-Jesús, A., & Costa-Ball, C. D. (2017). Validez y confiabilidad de

la Escala Satisfacción Familiar en estudiantes universitarios de Lima

Metropolitana, Perú. Actualidades en Psicología, 31(123), 90–99.

https://doi.org/10.15517/ap.v31i123.23573

Witt, K., Boland, A., Lamblin,

M., McGorry, P. D., Veness,

B., Cipriani, A., Hawton, K., Harvey, S.,

Christensen, H., & Robinson, J. (2019). Effectiveness of universal programmes

for the prevention of suicidal ideation, behaviour

and mental ill health in medical students: a systematic review and

meta-analysis. Evidence-Based Mental Health, 22(2), 84–90.

https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmental-2019-300082

World Health Organization. (2014). Preventing

Suicide: a Global Imperative. WHO; Geneva, Geneva.

World Health Organization. (2021). Suicidio.

World Health Organization.

https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide

World Health Organization. (2023). WHO Coronavirus

Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. World Health Organization.

https://doi.org/10.46945/bpj.10.1.03.01

Xia, Y., & Yang, Y. (2018). RMSEA, CFI, and TLI in

structural equation modeling with ordered categorical data: The story they tell

depends on the estimation methods. Behavior Research Methods, 51(1),

409–428. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-018-1055-2