http://dx.doi.org/10.24016/2020.v6n2.228

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Exposure to parental violence, child to parent

violence and dating violence of Mexican youth

Exposición a la violencia, violencia filioparental y en el noviazgo de jóvenes mexicanos

Daniela Cancino-Padilla 1;

Christian Alexis Romero-Méndez 2 and José Luis Rojas-Solís 3 *

1 Universidad

Juárez Autónoma de Tabasco, México.

2 Universidad

del Valle de Puebla, México.

3 Benemérita

Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, México.

* Correspondence: José Luis

Rojas-Solís. Facultad de Psicología, Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla.

Calle 4 Sur #403, Centro Histórico, 72000. Puebla, Puebla (México). Email: jlrojassolis@gmail.com

Received: February 19, 2020 | Revised: March 07,

2020 | Accepted: March 26, 2020 | Published Online: April 01,

2020

CITE IT AS:

Cancino-Padilla, D., Romero-Méndez,

C., & Rojas-Solís, J. (2020). Exposure to parental violence, child to parent

violence and dating violence of Mexican youth. Interacciones,

6 (2), e228. http://doi.org/10.24016/2020.v6n2.228

ABSTRACT

Background: Violence is a serious problem that has generated

worldwide concern because of the consequences it generates on those who suffer

it. However, although it has been studied in its various forms, the study of

violence against parents still has considerable research gaps. Therefore, this

work had the objective of analyzing violence against parents, dating violence

and observed between the parents to identify their frequency, as well as the

possible correlations between them. Methods: The final sample was made up

of 256 individuals between 18 and 30 years old. The Child to Parent Aggression

Questionnaire-Revised and the Conflict Tactics Scale - Modified version were

used. Results: The results indicated differences between the sexes

regarding the incidence of both violence against parents and dating violence,

as well as correlations between the variables studied and the bidirectionality

in violence. Conclusion: It is important to investigate these phenomena

more to understand them better, take the necessary measures and improve

prevention and intervention programs.

Keywords: Child to Parent Violence; Dating Violence;

Interparental Violence; Mexico.

RESUMEN

Introducción: La violencia es un problema grave

que ha generado preocupación a nivel mundial a causa de las consecuencias que

genera en quienes la sufren. Sin embargo, aunque ha sido estudiada en sus

diversas formas, el estudio de la violencia filioparental

aún conserva considerables lagunas en su investigación. Por lo tanto, este

trabajo tuvo el objetivo de analizar la violencia filioparental,

hacia la pareja y la observada entre los padres para identificar su frecuencia,

así como también las posibles correlaciones entre ellas. Método: La

muestra final se integró de 256 individuos de entre 18 y 30 años. Se emplearon

el cuestionario de violencia filioparental, la escala

de táctica de conflictos, en su versión modificada. Resultados: Los

resultados indicaron diferencias entre sexos respecto a la incidencia tanto de

la violencia filioparental como hacia la pareja, al

igual que correlaciones entre las variables estudiadas y la bidireccionalidad

en la violencia. Conclusiones: Resulta importante indagar más en dichos

fenómenos para comprenderlos mejor, tomar las medidas necesarias y mejorar los

programas de prevención e intervención.

Palabras clave: Violencia

filioparental; Violencia en el noviazgo; Violencia interparental; México.

BACKGROUND

The violence that arises in couple relationships, such as dating, is a problem that has generated a worldwide concern; It is a silent phenomenon that seriously affects those who suffer from it, in addition to this it seems that more and more vulnerable groups suffer from it; Therefore, their understanding is important in order to improve prevention actions and thus reduce their devastating effects on society (Batiza, 2017; Bayona, Chivita and Gaitan, 2015; Dardis, Dixon, Edwards and Turchik, 2015). At least in Mexico, psychological violence is the type of partner violence with the highest prevalence in women aged 15 years and over (40.1%), followed by economic violence (20.9%), physical violence (17.9%) and by last sexual violence (6.5%) (National Institute of Geography and Information Statistics, 2016).

In this sense, dating violence can be defined as the

threat or use of physical force, restraint, psychological abuse and / or sexual

abuse, which cause harm or discomfort to the couple (Morales and Rodríguez,

2012). It is a multifaceted phenomenon, as it can occur in different ways,

according to Leen et al. (2013), dating violence can be classified into three

main types: 1)Physical violence, which refers to the intentional use of

physical force with the potential to cause death, disability, injury or harm.

2) Psychological violence, which involves trauma caused by acts, threats or

coercive tactics, such as humiliating, controlling, withholding information or

doing something to make the victim feel diminished or ashamed. And 3) Sexual

violence, which includes three elements: a) the use of physical force to compel

a person to engage in a sexual act against their will, b) involves an

individual in an attempted or completed sexual act, who cannot understand the

nature or refuse to participate in it, and c) intentional, unwanted sexual

contact or intentional touching of someone with diminished capacity. Without

detriment to the above.

In the international scientific literature, the

prevalence of the various types of dating violence shows great variability,

despite this it could be said that psychological violence is the most reported

by young people, in that sense a higher prevalence is also suggested in the

perpetration of psychological violence by women and sexual violence by men (Alegría and Rodríguez, 2015; Rey-Anacona,

2013); In this regard, it is worth mentioning that in many studies the nature

of violence is bidirectional, that is, both sexes can be perpetrators and

victims of violence (Rojas-Solís, 2013; Rubio-Garay

et al., 2017).

However, numerous theories have been developed to

explain the phenomenon, among which the social and systemic learning stand out.

According to the first, the main learning mechanism of violent behaviors is

observational learning in the family environment, where an observation and

experience of violence can be developed, as well as a pronounced identification

in the observer because of their relationship affective with the model

(Bandura, 1982). On the other hand, from the systemic perspective, the

existence of multiple variables closely related to the dynamics of the couple

and involved in the origin and maintenance of violent behaviors such as

relationship patterns, communication, responses or conflict resolution is

pointed out;

Thus, among the variables most related to dating

violence are: attitudes to justify violence, the influence of peers, exposure

to violence within one's own family or in the community, a history of physical

abuse and psychological, sexual abuse and negative parenting habits,

traditional gender stereotypes, a deficit in social and communication skills,

inadequate anger management, low self-esteem, use of alcohol and other drugs, a

personal history of aggression, lack of empathy and lack of social support

(Rubio-Garay et al., 2015).

Following the same order of ideas, exposure to

violence within the family, and in particular that observed among parents, is a

risk factor for dating violence, as various studies have investigated the

relationship between these variables, finding that members from dysfunctional

families manifested a higher incidence of dating violence, and significant

associations between having witnessed violent behavior between parents and the

perpetration of violence against their partner (Alvarado, 2015; Bolívar, Rey

and Martínez, 2017; Makin-Byrd and Bierman, 2013; Martínez, Vargas and Novoa, 2016).

On the other hand, some of the consequences of dating

violence can be poor academic performance, school dropout, dissatisfaction with

the relationship, low self-esteem, insecurity, isolation, eating disorders,

anxiety and depression, post-traumatic stress symptoms, suicidal ideation,

normalization of violence and therefore, risk of being victimized in future

adult relationships, decrease in the use of contraceptive methods and early

pregnancy (Valdivia and González, 2014).

Child-to-Parent Violence

Considering that interpersonal violence is a

multifactorial and multifaceted phenomenon, lately attention has focused on a

previously ignored manifestation, it is the violence of children against their

parents or authority figures, which is known as child to parent violence (CPV; Rojas-Solís, Vázquez-Aramburu

and Llamazares-Rojo, 2016). Although it is

true that the violence of children towards their parents is not a really new

phenomenon, in countries like Mexico, studies on this problem are still scarce,

so it is necessary to provide greater attention and stimulate interest in this

problem in the community scientific (Molla-Esparza

and Aroca-Montolío, 2018; Vázquez-Sánchez et al.,

2019).

Without detriment to the foregoing, CPV could be

understood, according to Llamazares, Vázquez and Zuñeda (2013) and Pereira et al. (2017), like any repeated

harmful act, whether physical, psychological or economic, that the children

carry out against the parents or any other figure (family member or not) that

takes their place, with the main and ultimate objective of gaining power and /

or control over these, also achieving in this process different specific

objectives (materials or other benefits). This is how daughters can manifest

three types of behaviors: 1) Physical violence, which includes actions that can

cause bodily harm and injury; 2) Psychological violence, which includes

behaviors that threaten the feelings and affective needs of an individual; and

3) Economic violence,

Regarding the prevalence of

CPV, most studies indicate that male adolescents are the ones who exercise the

most violence towards their parents (with a percentage of 60% to 80% of the

total), while most of the studies affirm that female figures (mothers or other

caregivers such as grandmothers) are usually the center of abuse (Martínez et

al., 2015). However, some possible predictors of CPV are the abusive use of

substances, such as drugs and alcohol and, on the other hand, the presence of

previous factors, such as the difficulty of parents to comply with rules and

respect limits, or the influence of friendships (negative) and other family

models (del Moral et al., 2015).

Considering that violence

is an interpersonal phenomenon that is usually studied in a fragmented,

disjointed or separate way, although different types of violence (in its

different modalities) do not frequently appear separately, coexisting, what is

known as co-occurrence of violence, that is, the simultaneous presence of diverse

forms of violence (Hamby & Grych, 2013 cited by Rojas-Solís,

2015), this research has the objective to explore whether there is presence of

dating violence and its co-occurrence with CPV and that observed between

parents, in order to determine possible correlations between said phenomena.

In that sense, the specific objectives are to analyze

the frequency of violence in intimate relationships, violence observed in

parents and CPV, identify if there are differences by sex, and finally, find

the associations between violence in intimate relationships, violence observed

in parents and CPV.

The hypotheses derived from the objectives mentioned

above are set out below:

1. Child-parent violence will be committed more

frequently against the mother.

2. Women will exercise more frequent psychological

child-parent violence, and men physical child-parent violence.

3. In their relationships, women will exercise

psychological violence more frequently, and men physical violence.

4. Having suffered some type of violence in the partner

will be associated with the perpetration of it, that is, partner violence will

occur in a bidirectional way.

METHOD

Design

Study with a quantitative approach,

non-experimental, cross-sectional and ex post facto design, with exploratory,

descriptive and correlational purposes.

Participants

The sample was made up of university

students, the majority from the state of Tabasco (Mexico), for which the

following inclusion criteria were established: being between 18 and 30 years

old, having or having had at least one relationship; and have lived or live

with both parents. At the beginning, the responses of 338 individuals were

obtained, but following the inclusion criteria, the responses of those who had

not lived or did not live with both parents were discarded. The final sample

consisted of 256 subjects (68% women and 32% men), aged between 18 and 30 years

(M = 21, SD = 1.84), all with heterosexual orientation. The mean

duration of the current relationship in months was M = 26.06 (SD

= 20.64) and of the past relationship M = 11.48 (SD = 15.06).

Instruments

At the beginning, a sociodemographic study

was carried out to collect general data, followed by the implementation of the

following instruments:

The Adolescent Child-to-Parent Aggression

Questionnaire (Calvete et al., 2013), which assesses the violence

committed by individuals towards their parents and is composed of 10 items to

assess violence against the mother, and 10 items to assess it against the

father. The instrument is made up of two subscales: the physical VFP and the

psychological VFP. The items are evaluated with the Likert response scale of 4

anchors (0 = Never-this has not happened in my relationship with my mother or

father, 1 = Rarely-it has only happened on 1 or 2 occasions, 2 = Sometimes- It

has happened between 3 and 5 times and 3 = Very often - it has happened 6 or

more times). The validation of the questionnaire in Mexicans presented good

psychometric properties, its reliability was obtained through the alpha

coefficient, obtaining high indices (Calvete and Veytia, 2018). However,

The Conflicts Tactics Scale (Straus, 1979), was used to identify violent behaviors

observed between parents. The scale measures the way in which parents resolve

their conflicts as a couple and includes three subscales: psychological

violence, mild physical violence, and severe physical violence. The items are

evaluated with the Likert response scale of 5 anchors (1 = Never, 2 = Rarely, 3

= Sometimes, 4 = Often and 5 = Very often). This scale has been validated for

the Mexican population and demonstrated good indexes of internal consistency

(Straus and Mickey, 2012).

The Modified Conflicts Tactic Scale (Muñoz-Rivas et al., 2007): it was included to

recognize the presence of violence in the couple relationship. The scale

assesses the way individuals resolve conflicts with their partners and includes

items of a dual nature, showing information on both the violence committed and

the violence suffered. The instrument is divided into three subscales:

psychological violence, mild physical violence, and severe physical violence.

The items are evaluated with the Likert response scale of 5 anchors (1 = Never,

2 = Rarely, 3 = Sometimes, 4 = Often and 5 = Very often). The adaptation and

validation in the Mexican population was carried out by Ronzón-Tirado,

Muñoz-Rivas, Zamarrón and Redondo (2019) who obtained

high reliability indices.

Process

Once the virtual evaluation instrument was

formed, the link to answer it was disseminated through the Google Forms

platform, so that the participants could respond from their mobile devices or

computers at the time that is most convenient and comfortable for them. with a

duration of approximately 20 minutes. When the link to the questionnaire was

shared, a general presentation of the research objectives was made, and

emphasis was also placed on the confidentiality of the responses, ensuring

anonymity.

Ethical aspects

Regarding the ethical aspects, it is

necessary to emphasize that the measures suggested by the Mexican Society of Psychology

(2007) were adopted as well as those of the psychological research carried out

through virtual means (Eynon, Schroeder & Fry,

2012; Nosek, Banaji and Greenwald, 2002).

Data analysis

The analyzes were carried out through the

SPSS v. 22 for Windows, starting with the descriptive and inferential analyzes

and with the reliability analyzes of the subscales used by means of Cronbach's

alpha. To verify internal consistency, the values must be greater than 0.7 (Nunnaly and Bernstein (1994). Later, normality tests were

carried out, and after detecting non-normality in the responses, non-parametric

analyzes were carried out, such as the U test. of Mann Whitney to detect

significant differences between women and men. To determine the size of the

effect, the criteria of Cohen (1988) for the r of Rosenthal (rbis) were used: 0.1 = small effect, 0.3

= medium effect, 0.5 = large effect. To end, in order to analyze the existing

associations between the variables, the Spearman correlation coefficient (rho)

was used.

RESULTS

Internal consistency

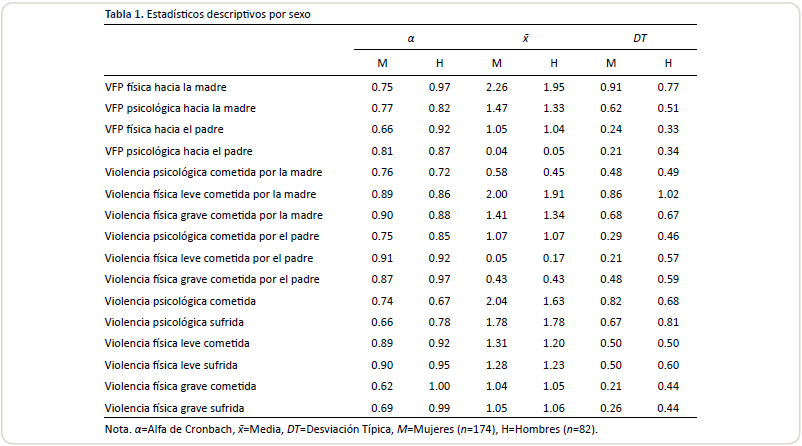

To begin with, the reliability analysis of

the subscales used was performed by means of Cronbach's alpha, obtaining very

acceptable levels, following the criteria suggested by Nunnaly and Bernstein (1994), in both women and men,

especially in the subscales of mild physical violence committed by the father

(.91 in women and .92 in men) and of mild physical violence suffered (.89 in

women and. 95 in men) (See Table 1).

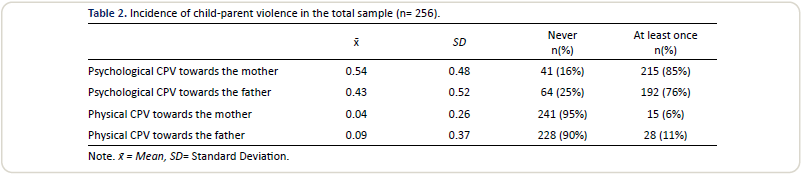

Prevalence of child-parent violence

As can be seen in Table 2, in the total

sample (women and men) the incidence of psychological CPV towards the mother is

higher, since 215 participants indicated that they committed this type of act

at least once. And with regard to physical CPV, its incidence towards the

father is higher, with 28 participants who indicated having exercised it at

least once.

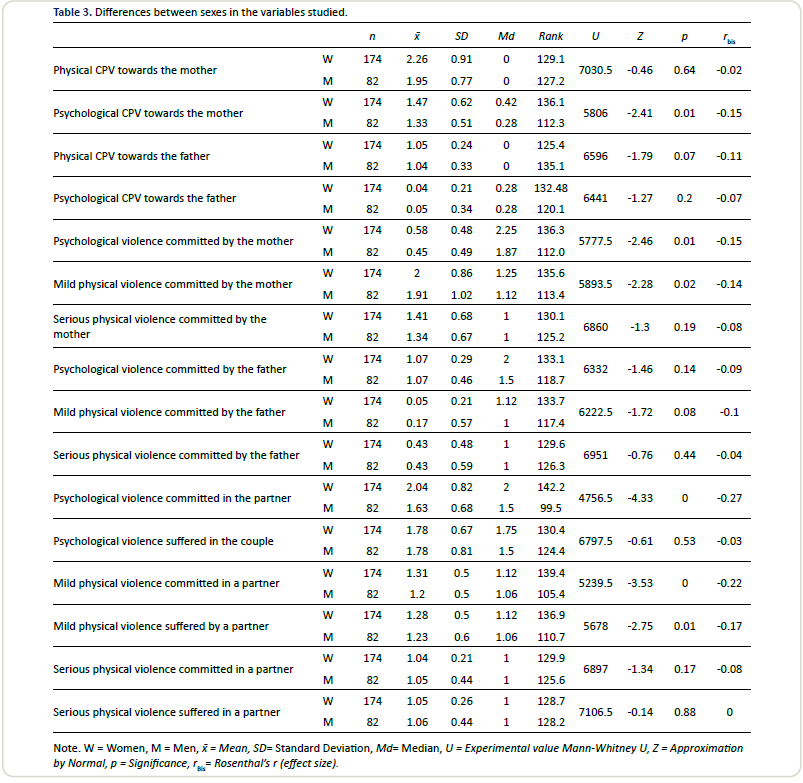

Differences by sex in the variables

studied.

The test results of U of Mann-Whitney revealed significant differences in

various types of violence. (See Table 3), although according to Cohen's (1988) criteria for determining the effect

size (.1 = small effect, .3 = medium effect, .5 = large effect), this was small

in most cases. For example, young women reported having perpetrated

psychological violence towards their parents more frequently than men (U

= 5806, Z = -2.41, p = 0.01, rbis =

-0.15).

Likewise, in the case of psychological

violence committed by the mother (U = 5777.5, Z = -2.46, p =

0.01, rbis = -0.15) and mild

physical violence committed (U = 5893.5, Z = -2.28, p = 0.02, rbis = -0.14) For the

mother, women reported having observed this phenomenon more than men. The

participants who indicated having committed psychological violence (U = 4756.5, Z = -4.33, p = 0.00, rbis = -0.27) and mild

physical (U = 5239.5, Z = -3.53, p = 0.00, rbis =-0.22) against their partners; In the same

way that they stated that they had suffered mild physical violence more

frequently (U = 5678, Z = -2.75, p = 0.006, rbis = -0.17) by their partners.

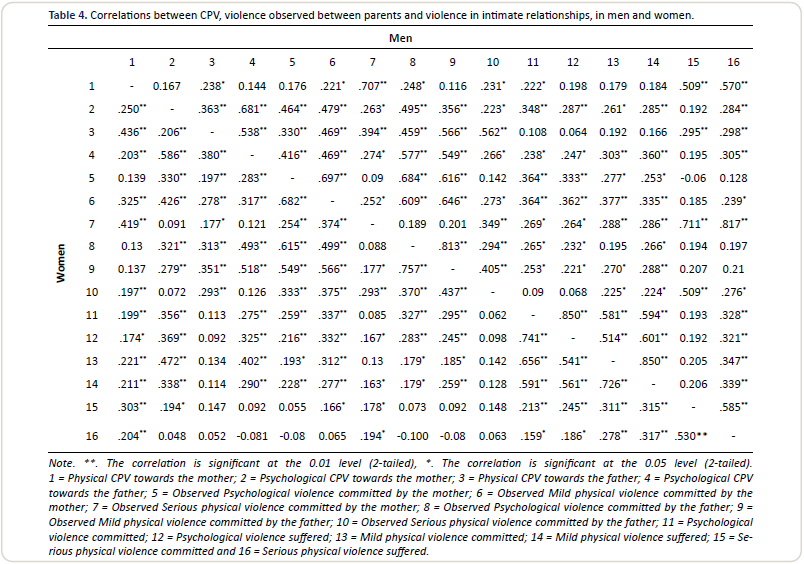

Associations between Child-to-Parent Violence

The results indicated that in the sample

of women there was a link between the psychological CPV against the father and

the psychological CPV against the mother (rho = .586, n =

174, p = .01), as well as between the physical CPV against the father and

physical CPV against the mother (rho = .436, n = 174, p =

.01). Regarding the sample of men, an association was found between the

psychological CPV against the father and the psychological CPV against the

mother (rho = .681, n = 82, p = .01), and also between the

physical CPV against the father and the psychological CPV against the father (rho

= .538, n = 82, p = .01). (See Table 4).

Associations between observed violence between parents

As can be seen in Table 4, in the sample of women positive and significant links were found, such as the one that associates mild physical violence perpetrated by the father and psychological violence perpetrated by the father (rho = .757, n = 174, p = .01), which relates the mild physical violence perpetrated by the mother and the psychological violence perpetrated by the mother (rho = .682, n = 174, p = .01), and also highlights the link between psychological violence perpetrated by the father and psychological violence perpetrated by the mother (rho = .615, n = 174, p = .01). Regarding the sample of men, many high and significant associations were also found, but for reasons of space, only the highest ones will be highlighted. So, first of all, we can mention the association between psychological violence perpetrated by the father and mild physical violence perpetrated by the father (rho=.813, n=82, p=. 01), secondly, the link between psychological violence perpetrated by the mother and mild physical violence perpetrated by the mother (rho=.697, n=82, p=.01), and thirdly, the link between psychological violence perpetrated by the mother and psychological violence committed by the father (rho=.684, n=82, p=.01).

Associations

between violence committed and suffered in intimate relationships

Regarding the violence committed and suffered, the

results found in the sample of women indicated significant correlation indices

between the psychological violence both committed and suffered (rho

= .741, n = 174, p = .01), as well as between mild physical violence committed

and suffered (rho = .726, n = 174, p = .01). And in the

sample of men, high and significant associations were found, such as that

between the psychological violence committed and suffered (rho

= .850, n = 82, p = .01), and the link between mild physical violence committed

and suffered (rho = .850, n = 82, p = .01).

Associations between the various types of violence

Finally, significant associations were

found between the various types of violence, as in the case of the sample of

women, where significant correlation indices were found between psychological

CPV against the father and mild physical violence perpetrated by the father (rho

= .518, n = 174, p = .01), as well as between psychological CPV against the

father and psychological violence perpetrated by the father (rho

= .493, n = 174, p = .01). Regarding the sample of men, significant

correlations were obtained between the severe physical violence suffered and

the severe physical violence perpetrated by the mother (rho =

.817, n = 82, p = .01), between the serious physical violence committed and

serious physical violence perpetrated by the mother (rho =

.711, n = 82, p = .01), and between severe physical violence perpetrated by the

mother and physical CPV against the mother (rho = .707, n =

82, p=.01).

DISCUSSION

The objective of this

research was to study the frequency of Child-to-Parent Violence and its

co-occurrence with violence in intimate relationships and that observed between

parents and the co-occurrence between these phenomena, in students from a

public university in the southeast of Mexico; For this, specific hypotheses

have been proposed, which are discussed below.

With reference to the first

hypothesis raised in this study, it was expected that CPV would be more

frequent in mothers, as some studies have suggested (Calvete,

Gámez-Guadix, & Orue,

2014; Calvete, Orue, and

González-Cabrera, 2017). Notwithstanding the above, it was only evident in the

results obtained for the psychological CPV, since the physical CPV was suffered

mostly by the parents, agreeing on both issues with what was found by Vázquez-Sánchez

et al. (2019), as withÁlvarez, Sepúlveda

and Espinoza (2016). On the other hand, the data contrasted with that found by Ibabe (2015), who found no significant differences in the

perpetration of physical violence based on the sex of the parents, while Calvete and Veytia (2018) found a

higher incidence in all types of violence (psychological, severe psychological,

physical and severe physical) towards the mother. The presence of CPV against

the mother could be explained by the fact that mothers are the ones who usually

assume the role of raising their children, tend to spend more time alone with

them and can be perceived as weak (Martínezet al., 2015).

Regarding the second hypothesis,

“women exercise psychological CPV more frequently and men physical CPV”

(Lozano, Estévez & Carballo, 2013), this

differentiation was only manifested in psychological CPV against the mother,

whose prevalence was higher in women. On the other hand, according to the rest

of the CPV subscales, there were no significant differences between sexes,

coinciding with what was indicated by Aroca-Montolío,

Lorenzo-Moledo and Miró-Pérez (2014). Such results

differ from what was found by Ibabe, Jaureguizar and Bentler (2013),

who found that sons directed more physical CPV towards their parents than

daughters. These results could be explained from the intergenerational theory

of violence, according to which the observation or suffering of abuse in the family

context is a risk factor for children, enabling the learning of both passive

(being a victim) and violent (being an aggressor) behaviors that could be

exercised in the future (Molla-Esparza and Aroca-Montolío, 2018). In support of the above, in this

research correlations were found between psychological CPV against the father

and mild physical violence perpetrated by the father, as well as between the psychological CPV against the father and

the psychological violence perpetrated by the father on the daughters.

Likewise, a significant correlation was found between severe physical violence

perpetrated by the mother and physical CPV against the mother in the children.

Regarding the third hypothesis, it

was expected that women would exercise psychological violence more frequently,

and men physical violence (Alegría and Rodríguez, 2015). Well, the results

indicated significant differences between the sexes with women exceeding men,

reaffirming the first part of the third assumption and agreeing with that mentioned

by Rubio-Garay et al., (2017). However, it could not

be confirmed that men exercised physical violence more frequently and, on the

contrary, as has already been indicated in various studies (Cortés-Ayala et

al., 2015; Marasca and Falcke, 2015; Martínez, Vargas

and Novoa, 2016; Nava-Reyes et al., 2018; Peña et

al., 2018; Rodríguez, Riosvelasco and Castillo, 2018;

Wincentak, Connolly and Card, 2017), women

perpetrated physical violence to a greater extent. In accordance withGracia-Leiva (2019), one of the most controversial

topics of dating violence is the differences by sex in the prevalence of both

perpetration and victimization, since some investigations more frequently point

to men as aggressors, others to women, and a few others indicate high rates of

bidirectionality; Furthermore, if they find differences, or if they find higher

rates of violence in women, the statistical magnitude of the difference is

small, a possible cause being the fact that such studies do not take into

account the underestimation rates of violence by women . On the other hand,

some studies have highlighted that men tend to reject violence less, so they

justify it more than women; Similarly, several authors have pointed out the

fact that men are more likely to legitimize violence as a response, downplaying

it, while women overvalue their actions, causing them to feel guilty for them (Pazos, Oliva & Hernando, 2014) .

It goes without saying that, fortunately, the frequency of violence committed

and suffered found in the population was low, results that agree with findings

such as those of Celis-Sauce and Rojas-Solís (2015).

On the other hand, it was expected

to corroborate that having suffered some type of violence in the partner would

be associated with the perpetration of it, that is, that partner violence would

occur in a bidirectional manner. In this sense, significant correlations were

obtained between the perpetration and victimization of psychological violence,

as well as mild physical violence, thus corroborating the fourth assumption. In

this vein, it is pertinent to remember that in the present investigation, both

the sample of women and men found significant correlations between the psychological violence committed and

suffered, as well as between the mild physical violence committed and suffered,

coinciding with Celis-Sauce and Rojas-Solís (2015).

This is how the bidirectionality of the phenomenon became evident, already

present in multiple studies (Cortés-Ayala et al., 2015; Fernández-González,

O'Leary and Muñoz-Rivas, 2013; Palmetto et al., 2013; Valdivia and González,

2014), confirming the final assumption.

It is worth mentioning that

bidirectionality was also found in the link obtained between the psychological

violence observed between the parents, since in men, a positive correlation was observed between

severe physical violence perpetrated by the mother and severe physical violence

perpetrated against a partner.

On the other hand, and following what is suggested by

other authors (Ibabe, Arnoso

and Elgorriaga, 2020; Pacheco, 2015) regarding that

those who have observed or witnessed violence between their parents could

present violent behaviors in their dating relationships, a correlation was

found between serious physical violence perpetrated by the mother and serious

physical violence suffered in the courtship. Among other reasons, this could

happen as a result of what has been experienced in family dynamics, in such a

way that this type of violence is allowed in couple relationships after normalization

and acceptance as a means of resolving conflicts, (from Alencar-Rodrigues

and Cantera, 2012), so that exposure to violence could be a predictor of dating

violence (Bonilla-Algovia and

Rivas-Rivero, 2019).

Limitations

and strengths

Within the methodological limitations of this research

are the type of sampling used (non-probabilistic) and the disproportion between

the number of women and men participating, added to this it is necessary to

indicate that both the CTS and the M-CTS are not instruments intended entirely

to the evaluation of violence, but rather conflict resolution tactics, so the

results derived from them require caution when associated with violence

committed or suffered.

Future

lines of research

The authors suggest investigating more about CPV,

since, as mentioned above, it is a field in which there is still much to be

explored, especially with its current characteristics (Molla-Esparza

and Aroca-Montolío, 2018). And although violence in

relationships is a much more discussed topic, its evolution is constant,

especially when other types of relationships continue to emerge (free, friend,

etc.), so it would be pertinent to continue investigating such phenomenon;

without forgetting the necessary inclusion of other types of populations such

as same-sex couples, from rural areas, not in school or indigenous.

CONCLUSION

Finally, the results obtained are intended to

contribute to the empirical corpus on the co-occurrence of different forms of

violence in adolescents, especially in young people from Tabasco; Among other

implications, the fact of child-parent violence (psychological and physical)

stands out, as well as against the partner (psychological, mild physical and,

to a lesser extent, severe physical) is becoming evident in both women and men,

therefore Furthermore, they seem to have a bidirectional character both in the

participants and in their parents. These data, with due precautions, indicate

the need to implement violence prevention and intervention programs in all areas

and, especially, to avoid continuing to fragment the study of interpersonal and

intrafamily violence.

ORCID

Daniela Cancino-Padilla https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8430-7218

Christian Alexis

Romero-Méndez https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4851-7116

José Luis

Rojas-Solís http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6339-4607

FUNDING

Self-financed.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

No conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The student Daniela Cancino-Padilla wrote part of this article within the

Summer of Scientific and Technological Research of the Pacific, Dolphin

Program; the student Christian Alexis Romero-Méndez wrote part of this

manuscript within the Summer of Scientific Research - Mexican Academy of

Sciences Study carried out within the Academic Body (BUAP-CA-330): “Prevention

of violence: Educating for a Culture of Peace through Social Participation”.

REFERENCES

Alegría, M., & Rodríguez, A. (2015).

Violencia en el noviazgo: perpetración, victimización y violencia mutua. Una

revisión. Actualidades en

Psicología, 29(118), 57-72.

http://dx.doi.org/10.15517/ap.v29i118.16008

Alvarado, G. P. A. A. (2015). Transmisión

transgeneracional de la violencia de pareja y funcionalidad familiar de hombres

y mujeres de la ciudad de Trujillo. In Crescendo, 6(2),

11-21. https://doi.org/10.21895/incres.2015.v6n2.02.

Álvarez, A. A. J., Sepúlveda, G. R. E.,

& Espinoza, M. S. M. (2016). Prevalencia de la violencia filio-parental en

adolescentes de la ciudad de Osorno. Pensamiento y Acción Interdisciplinaria,

1(1), 59-74. Recuperado de:

http://revistapai.ucm.cl/article/view/156/151

Aroca-Montolío,

C., Lorenzo-Moledo, M., & Miró-Pérez, C. (2014). La violencia

filio-parental: un análisis de sus claves. Anales de Psicología, 30(1) 157-170. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.30.1.149521

Bandura,

A. (1982). Teoría del Aprendizaje

Social. Madrid: Espasa Universitaria.

Batiza,

A. F. J. (2017). La violencia de pareja: Un enemigo silencioso. Archivos de Criminología, Seguridad Privada

y Criminalística, 18, 144-151. Recuperado de:

https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=5813533

Bayona, L., Chivita, A. V. & Gaitan, D. C. (2015). Violencia de pareja y construcción de

discurso sobre la subjetividad femenina. Informes Psicológicos, 15(1),

127-143. http://dx.doi.org/10.18566/infpsicv15n1a07

Bolívar,

S. Y., Rey, A. C. A. & Martínez, G. J. A. (2017). Funcionalidad familiar,

número de relaciones y maltrato en el noviazgo en estudiantes de

secundaria. Psicología desde el Caribe, 34(1). Recuperado de:

https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6552639

Bonilla-Algovia,

E., & Rivas-Rivero, E. (2019). Violencia en el noviazgo en estudiantes

colombianos: relación con la violencia de género en el entorno. Interacciones,

5(3). http://dx.doi.org/10.24016/2019.v5n3.197

Calvete, E., Gámez-Guadix, M., & Orue, I. (2014). Características familiares asociadas a violencia

filio-parental en adolescentes. Anales de psicología, 30(3),

1176-1182. http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.30.3.166291

Calvete, E., Gámez-Guadix, M., Orue, I., González-Diez, Z., de Arroyabe, E.

L., Sampedro, R., ..., & Borrajo, E. (2013). Brief report: The

Adolescent Child-to-Parent Aggression Questionnaire: An examination of

aggressions against parents in Spanish adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 36(6), 1077-1081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.08.017

Calvete, E., Orue,

I., & González-Cabrera, J. (2017). Violencia filio parental: comparando lo

que informan los adolescentes y sus progenitores. Revista de Psicología

Clínica con Niños y Adolescentes, 4(1), 9-15. Recuperado de:

https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=5789314

Calvete, E., & Veytia, M. (2018).

Adaptación del Cuestionario de Violencia Filio-Parental en Adolescentes

Mexicanos. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 50(1), 49-59.

http://dx.doi.org/10.14349/rlp.2018.v50.n1.5.

Caridade, S., Braga, T. & Borrajo, E. (2019).

Cyber

dating abuse (CDA): Evidence from a systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 48, 152-168.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2019.08.018

Celis-Sauce, A., &

Rojas-Solís, J. L. (2015). Adolescentes

mexicanos como víctimas y perpetradores de violencia en el noviazgo. Reidocrea, 4, 60-65. Recuperado de:

http://hdl.handle.net/10481/35150

Cohen, J.W. (1988). Statistical power

analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd edn). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Cortés-Ayala, L., Flores, M., Bringas,

C., Rodríguez-Franco, L., López-Cepero, J., & Rodríguez, F. J. (2015).

Relación de maltrato en el noviazgo de jóvenes mexicanos: análisis diferencial

por sexo y nivel de estudios. Terapia psicológica, 33(1),

5-12. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-48082015000100001

Dardis, C. M., Dixon,

K. J., Edwards, K. M., & Turchik, J. A. (2015). An examination of

the factors related to dating violence perpetration among young men and women

and associated theoretical explanations: A review of the literature. Trauma, Violence,

& Abuse, 16(2), 136-152.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838013517559

de

Alencar-Rodrigues, R., & Cantera, L. (2012).

Violencia de género en la pareja: Una revisión teórica. Psico, 41(1),

116-126. Recuperado de: https://ddd.uab.cat/record/130820?ln=es

del Moral, A. G., Martínez, F. B.,

Suárez, R. C., Ávila, G. M. E., & Vera, J. J. A. (2015). Teorías sobre el

inicio de la violencia filio-parental desde la perspectiva parental: un estudio

exploratorio. Pensamiento Psicológico, 13(2), 95-107.

http://dx.doi.org/10.11144/Javerianacali.PPSI13-2.tivf

Eynon, R., Schroeder,

R. y Fry, J. (2009) New techniques in online research: Challenges for research

ethics, Twenty-First Century Society, 4(2),

187-199. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450140903000308

Fernández-González,

L., O’Leary, K. D., & Muñoz-Rivas, M. J. (2013). We Are Not

Joking: Need for controls in reports of dating violence. Journal of

Interpersonal Violence, 28(3), 602–620.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260512455518

Gracia-Leiva, M., Puente-Martínez, A.,

Ubillos-Landa, S., & Páez-Rovira, D. (2019). La violencia en el noviazgo

(VN): una revisión de meta-análisis. Anales de Psicología, 35(2), 300-313. http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.35.2.333101

Ibabe, I. (2015). Family predictors

of child-to-parent violence: the role of family discipline. Anales De Psicología, 31(2), 615-625.

http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.31.2.174701

Ibabe, I., Arnoso,

A., & Elgorriaga, E. (2020). Child-to-Parent Violence as an Intervening Variable in

the Relationship between Inter-Parental Violence Exposure and Dating Violence. International

Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(5), 1514. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051514

Ibabe, I., Jaureguizar, J., & Bentler, P. M. (2013). Risk factors for

child-to-parent violence. Journal of family violence, 28(5), 523-534.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-013-9512-2

Instituto Nacional de Estadística

Geografía e Informática (2016). Encuesta

Nacional sobre la Dinámica de las Relaciones en los Hogares (ENDIREH). México, D.F.:

Autor.

Leen, E., Sorbring, E., Mawer, M.,

Holdsworth, E., Helsing, B. & Bowen, E. (2013).

Prevalence, dynamic risk factors and the efficacy of primary interventions for adolescentdating violence: An international review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 18,

159–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2012.11.015

Llamazares, A., Vázquez, G. & Zuñeda,

A. (2013). Violencia filio-parental: propuesta de explicación desde un modelo

procesual, Boletín de Psicología, 109,

85-99. Recuperado de: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=4495413

Lozano,

S., Estévez, E. & Carballo, J. L. (2013). Factores individuales y

familiares de riesgo en casos de violencia filio-parental. Documentos

de trabajo social: Revista de trabajo y acción social, 52, 239-254.

Recuperado de: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=4703109

Makin-Byrd, K.

& Bierman, K. L. (2013). Individual and

family predictors of the perpetration of dating violence and victimization in

late adolescence. Journal of youth and adolescence, 42(4),

536-550. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-012-9810-7

Marasca, A. R.,

& Falcke, D. (2015). Forms of violence in the

affective-sexual relationships of adolescents. Interpersona:

An International Journal on Personal Relationships, 9(2),

200-214. http://dx.doi.org/10.23668/psycharchives.2210

Martínez G. J.

A., Vargas G. R. & Novoa G. M. (2016). Relación entre la violencia en el

noviazgo y observación de modelos parentales de maltrato. Psychologia.

Avances de la disciplina, 10(1),101-112. Recuperado de:

http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1900-23862016000100010

Martínez,

J. A., Vargas, R., & Novoa, M. (2016). Relación entre la violencia en el

noviazgo y observación de modelos parentales de maltrato. Psychologia. Avances de la disciplina 10(1), 101-112. Recuperado de:

http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=297245905010

Martínez,

M. L., Estévez, E., Jiménez, T. I., & Velilla, C. (2015). Child-parent violence: main characteristics, risk

factors and keys to intervention. Papeles

Del Psicólogo, 36(3), 216-224.

Recuperado de: http://www.papelesdelpsicologo.es/English/2615.pdf

Molla-Esparza, C., & Aroca-Montolío, C. (2018). Menores que maltratan a sus

progenitores: definición integral y su ciclo de violencia. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica, 28(1).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apj.2017.01.001

Morales,

D. N. E., & Rodríguez, T. V. (2012). Experiencias de violencia en el

noviazgo de mujeres en Puerto Rico. Revista puertorriqueña de

psicología, 23, 57-90. Recuperado de:

http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1946-20262012000100003

Muñoz-Rivas,

M.J., Andreu, R. J. M., Graña, G. J. L., O’Leary, D. K. & González, M.P.

(2007). Validación de la versión modificada de la Conflicts

Tactics Scale (M-CTS) en

población juvenil española. Psicothema, 19(4),

692-697. Recuperado de:

https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=2389574

Nava-Reyes, M. A., Rojas-Solís, J. L., de

la Paz Toldos-Romero, M., & Morales-Quintero, L. A. (2018). Factores de

género y violencia en el noviazgo de adolescentes. Boletín Científico

Sapiens Research, 8(1), 54-70. Recuperado

de: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6705582

Nosek, B. A., Banaji,

M. R., & Greenwald, A. G. (2002). eResearch:

Ethics, security, design, and control in psychological research on the

Internet. Journal of Social Issues, 58,

161-176

Nunnaly, J. C. y Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd Ed.). New York,

NJ: McGraw-Hill.

Ospina,

M. & Clavijo, K. A. (2016). Una mirada sistémica a la violencia de pareja:

dinámica relacional, ¿configuradora del ciclo de violencia conyugal? Textos y Sentidos, 14, 105-122.

Recuperado de: http://hdl.handle.net/10785/3504

Pacheco, V. M. J. (2015). Actitud hacia

la violencia contra la mujer en la relación de pareja y el clima social

familiar en adolescentes. Interacciones, 1(1),

29-44. http://dx.doi.org/10.24016/2015.v1n1.2

Palmetto, N., Davidson, L. L., Breitbart, V. &

Rickert, V. I. (2013). Predictors of physical intimate partner violence in the

lives of young women: Victimization, perpetration, and bidirectional violence. Violence and Victims, 28(1), 103-121. http://dx.doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.28.1.103

Pazos, G. M., Oliva, D A., &

Hernando, G. Á. (2014). Violencia en relaciones de pareja de jóvenes y

adolescentes. Revista latinoamericana de psicología, 46(3),

148-159. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0120-0534(14)70018-4

Peña, F., González B. Z., Sotelo K. V.,

Martínez J. I. V., Narváez Y. V., Rodríguez G. I. H., Parra, S. V. & Ruíz

R. L. (2018). Violencia en el noviazgo en jóvenes y adolescentes en la frontera

norte de México. Journal Health NPEPS, 3(2), 426-440. http://dx.doi.org/10.30681/252610103117

Pereira, R., Loinaz, C. I., del Hoyo-Bilbao, J., Arrospide, J., Bertino, L., Calvo, A., ... & Gutiérrez,

M. M. (2017).

Propuesta de definición de violencia filio-parental: Consenso de la Sociedad

Española para el estudio de la Violencia Filio-Parental. Papeles del

psicólogo, 38(3), 216-223. https://doi.org/10.23923/pap.psicol2017.2839

Rey-Anacona, C. A. (2013). Prevalencia y

tipos de maltrato en el noviazgo en adolescentes y adultos jóvenes. Terapia

psicológica, 31(2), 143-154.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-48082013000200001

Rodríguez, H. R., Riosvelasco,

M. L., & Castillo, V. N. (2018). Violencia en el noviazgo, género y apoyo

social en jóvenes universitarios. Escritos de psicología, 11(1),

1-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.5231/psy.writ.2018.2203

Rojas-Solís, J. L. (2013). Violencia en

el noviazgo de universitarios en México: Una revisión. Revista Internacional de Psicología, 12(02).

https://doi.org/10.33670/18181023.v12i02.71

Rojas-Solís,

J. L. (2015). Nuevos derroteros en la investigación psicosocial de la

violencia. Enseñanza e Investigación en Psicología, 20(2),240-242.

Recuperado de: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=29242799015

Rojas-Solís,

J. L., Vázquez-Aramburu, G., & Llamazares-Rojo, J. A. (2016). Violencia

filio-parental: una revisión de un fenómeno emergente en la investigación

psicológica. Ajayu. 14(1), 140-161. Recuperado de:

http://www.scielo.org.bo/scielo.php?pid=S2077-21612016000100007&script=sci_arttext

Romo-Tobón, R. J., Vázquez-Sánchez, V.,

Rojas-Solís, J. L., & Alvídrez, S. (2020). Cyberbullying

y Ciberviolencia de pareja en alumnado de una

universidad privada mexicana. Propósitos

y representaciones, 8(2). http://dx.doi.org/10.20511/pyr2020.v8n2.303

Ronzón-Tirado, R. C., Muñoz-Rivas, M. J.,

Zamarrón, M. D., & Redondo, N. (2019). Cultural

Adaptation of the Modified Version of the Conflicts Tactics Scale (M-CTS) in

Mexican Adolescents. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 619.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00619

Rubio-Garay, F., Carrasco, M. Á., Amor, P. J., &

López-González, M. A. (2015). Factores

asociados a la violencia en el noviazgo entre adolescentes: una revisión

crítica. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica, 25(1), 47-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apj.2015.01.001

Rubio-Garay,

F., López-González M. Á., Carrasco M.A. & Amor P. J. (2017). Prevalencia de

la violencia en el noviazgo: una revisión sistemática. Papeles del

psicólogo, 38(2), 135-147.

Recuperado de: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6029503

Sociedad Mexicana

de Psicología. (2007). Código ético del

psicólogo (4ª edición). México, D.F.: Editorial Trillas.

Straus, M. A.

(1979). Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The Conflict Tactics (CT)

Scales. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 41(1), 75-88.

https://doi.org/10.2307/351733

Straus, M., & Mickey, E. (2012). Reliability,

validity, and prevalence of partner violence measured by the conflict tactics

scales in male-dominant nations. Aggression

and Violent Behavior, 17, 463-474.

https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1016/j.avb.2012.06.004

Valdivia, M. P., & González, L. A. (2014). Violencia

en el noviazgo y pololeo: una actualización proyectada hacia la

adolescencia. Revista de Psicología, 32(2), 329-355.

Recuperado de:

http://www.scielo.org.pe/scielo.php?pid=S0254-92472014000200006&script=sci_arttext

Vázquez-Sánchez, V., Romo-Tobón, R. J.,

Rojas-Solís, J. L., González Flores, M. D. P., & Rey Yedra, L. (2019).

Violencia filio-parental en adultos emergentes mexicanos: Un análisis

exploratorio. Revista Electrónica de Psicología Iztacala, 22(3),

2534-2551. Recuperado de:

https://www.medigraphic.com/cgi-bin/new/resumen.cgi?IDARTICULO=89678

Wincentak, K., Connolly,

J., & Card, N. (2017). Teen dating violence: A meta-analytic review of

prevalence rates. Psychology

of Violence, 7(2), 224-241. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0040194