http://dx.doi.org/10.24016/2020.v6n3.171

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Adaptation of the Beck Anxiety Inventory

in population of Buenos Aires

Adaptación del

Inventario de Ansiedad de Beck en población de Buenos Aires

Nicolás

Alejandro Vizioli 1 *, Alejandro Emilio Pagano 1

1 Universidad de Buenos Aires, Faculty of

Psychology, Argentina.

* Correspondence: nicovizioli@gmail.com.

Received: July 02, 2020 | Revised:

September 08, 2020 | Accepted: September

13, 2020 | Published Online:

September 14, 2020.

CITE IT AS:

Vizioli, N. & Pagano, A. (2020). Adaptation of the

Beck Anxiety Inventory in population of Buenos Aires. Interacciones, 6(3), e171.https://doi.org/10.24016/2020.v6n3.171

ABSTRACT

Background: Currently, anxiety disorders are the most

prevalent worldwide, reaching a rate of 5% in Argentina in 2017. The Beck

Anxiety Inventory (BAI) is one of the instruments most used in research and

clinic today. In its construction, one of the objectives was to evaluate

anxiety symptoms that are not usually evident in depressive disorders, which is

why it is a relevant test to make a differential diagnosis. The objective of

this study was to adapt the BAI to adult population of Buenos Aires. Methods: A direct translation of the

inventory and then an expert judgment to assess the content validity were

carried out. The discrimination capacity of the items was analyzed, and the

structural validity of the test were evaluated according to different models

found in the literature. Also, the internal consistency of the instrument was

analyzed. Results: The adaptation

presents adequate content validity and the items have been shown to

discriminate adequately. As for the confirmatory factor analyzes, the most

parsimonious solution, which indicates the one-dimensionality of the construct,

was chosen, providing evidence of construct validity. The adaptation presents

adequate internal consistency. Tentative normative values are offered. Conclusion: Evidence of validity and

reliability has been found for the Argentine adaptation of the BAI. It is

considered an instrument of great clinical utility.

Keywords: BAI; Anxiety; Population of Buenos Aires; Content validity; Construct

validity; Internal consistency.

RESUMEN

Introducción: En la actualidad

los trastornos de ansiedad son los de mayor prevalencia a nivel mundial,

llegando a una tasa del 5% en Argentina en el año 2017. En ese sentido, el

Inventario de Ansiedad de Beck (BAI) es uno de los instrumentos más utilizados

en investigación y clínica en la actualidad. En su construcción uno de los

objetivos fue evaluar síntomas de ansiedad que no suelen evidenciarse en

trastornos depresivos, motivo por el cual resulta un test relevante para

realizar un diagnóstico diferencial. El objetivo de este estudio fue adaptar el

BAI a población adulta de Buenos Aires.

Método: Se realizó una traducción directa del inventario y luego un juicio

de expertos para evaluar la validez de contenido. Se analizó la capacidad de

discriminación de los reactivos y se evaluó la validez estructural de los

diferentes modelos encontrados en la literatura. A su vez, se analizó la

consistencia interna del instrumento.

Resultados: La adaptación presenta adecuada validez de contenido y los

reactivos han demostrado discriminar de forma adecuada. A su vez, a partir de

los análisis factoriales confirmatorios realizados se optó por la solución más

parsimoniosa que indica la unidimensionalidad del constructo aportando evidencia

de validez de constructo. A su vez, la adaptación presenta una adecuada

consistencia interna. Se ofrecen valores normativos tentativos. Conclusión: Se han hallado evidencias

de validez y confiablidad para la adaptación argentina del BAI. Se lo considera

un instrumento de gran utilidad clínica.

Palabras clave: BAI; Ansiedad; Población de Buenos Aires; Validez de Contenido;

Validez de Constructo; Consistencia Interna.

BACKGROUND

Anxiety disorders are ranked as the most

prevalent disorders worldwide (Ritchie & Roser, 2018). In Argentina,

anxiety disorders constitute the group with the highest prevalence, followed by

mood disorders (Stagnaro et al., 2017). The relationship between both disorders

has been well documented in the research literature. Even the similarity of

symptoms between anxiety and depressive disorders can make investigation,

diagnosis and treatment difficult (Mountjoy and Roth, 1982). This problem can

be explained due to the cognitive biases shared by both pathologies, as well as

their frequent comorbidity. In this sense, cognitive biases in judgment and

interpretation of situations are common for both disorders, as well as

predominantly negative affection (Mineka, Watson & Clark, 1998).

In relation to the

comorbidity between anxiety and depressive disorders, it has been found that a

large part of people with anxiety disorders also experience depressive

disorders, and vice versa (Gorman, 1996). Even transdiagnostic treatments have

been developed that allow working with both problems, as is the case with the

unified protocol proposed by Barlow et al. (2016). This protocol is

characterized by addressing the common mechanism underlying both disorders:

emotional regulation. In this regard, it has been found that maladaptive

emotional regulation strategies can be common processes across various

psychological disorders (Aldao et al., 2010).

Also, calamitous events such as natural

disasters or attacks can cause a substantial increase in anxiety symptoms

(Clark & Beck, 2011). In 2020, different countries of the world have been

affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. The psychological impact caused by this

situation has caused an increase in anxiety and depressive symptoms (Rajkumar,

2020).

In this context, the evaluation and

follow-up of the problems associated with anxiety is fundamental, given that

they impose a great individual and social burden, tend to be chronic and can be

disabling (Lépine, 2002). Accordingly, it has been found that anxiety and

depression disorders involve a large part of the economic resources destined to

the treatment of psychological disorders (Ruiz-Rodríguez, 2017). However, it

has been estimated that only a quarter of the people who meet the criteria for

anxiety disorders have received treatment (Alonso et al., 2018).

Due to the aforementioned, it is necessary

to have valid and reliable instruments that allow a correct measurement of

anxiety and can discriminate these pictures from depressive disorders. In this

sense, the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI;Beck et al., 1988) was designed with a double

objective: to measure anxiety in a valid and reliable way and to discriminate

anxiety from depression (Sanz & Navarro, 2003). This anxiety assessment

instrument is also the most cited in scientific databases (Piotrowski, 2018),

as well as one of the most used in clinical and non-clinical populations both

in psychotherapeutic practice and in research (Magán et al., 2008).

For this reason, the

general objective of this research was to carry out the conceptual, linguistic

and metric adaptation of the Beck Anxiety Inventory in the general adult

population of the City of Buenos Aires and the Greater Buenos Aires. In this

way, the specific objectives proposed were a) to examine evidence of content

validity; b) analyze the discrimination capacity of the items; c) obtain

evidence of structural and construct validity; d) study the internal consistency

of scores; e) establish normative values.

METHODS

Participants

The sampling was non-probabilistic and

intentional. The sample consisted of 269 subjects, of which 49.4% resided in

the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires and 50.60% in the Province of Buenos Aires.

In relation to gender, 37.5% were male, 60.6% female, and 1.9% preferred not to

communicate it. Regarding the age of the participants, there were cases between

18 and 76 years (M = 32.35, SD = 12.17). Regarding educational level, 1.5%

presented complete primary school, 57.5% completed secondary school and 41%

reported having completed university studies. Finally, it was consulted whether

they had been diagnosed with any psychological problems, 86.2% reported not

being diagnosed, 7.1% mentioned being diagnosed with an anxiety disorder, 3.3%

depression and the remaining 3.4% other problems such as post-traumatic stress,

eating and personality disorders.

Instruments

First,

a sociodemographic questionnaire was designed to collect information on the

place of residence, age, gender, educational level, and history of

psychological diagnoses.

Second, the Spanish translated version of

the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI, Beck, Epstein, Brown & Steer, 1988) was

used. This inventory presents 21 items with a format designed to assess the

severity of clinical anxiety symptoms. Each BAI item reflects an anxiety

symptom and for each one, respondents rate the degree to which they were

affected by it during the last week, on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 0

(Not at all) to 3 (Severely - I get very upset). Regarding the score, each item

is assigned from 0 to 3 points, depending on the response of the individual

and, after directly adding the score for each item, a total score can be

obtained, ranging from 0 to 63.

Process

The

collection of analysis units was carried out through the use of virtual

platforms. An informed consent was included in which the details of the

objectives of the present investigation were specified, together with the

guarantees of confidentiality and anonymity. It was explained to the

participants that they could desist from participating at the moment they

considered it and in turn they were given an email to communicate in case they

felt discomfort when answering the questionnaire.

Data analysis

First, the translation

of the inventory was carried out according to the recommendations of Muñiz et

al. (2013), using the direct translation method in order to find linguistic and

cultural equivalence. Three bilingual experts with experience in instrument

translation were asked to each carry out a direct translation of the

questionnaire from English to Spanish. Once the three versions were obtained in

Spanish, a committee of experts was convened that could analyze the

translations made, in this way the most appropriate translations in linguistic

and cultural terms were then selected.

The expert trial

(Andreani, 1975) was carried out following the recommendations of Escobar-Pérez

and Cuervo-Martínez (2008). The criteria for selecting these judges were: a)

previous experience in conducting judgement of experts b) expert in

psychometrics and psychological evaluation c) knowledge on psychopathology e)

knowledge about construct anxiety. Once the five expert

judges were selected, the instructions and forms were prepared to be provided

by mentioning the objectives of the study and the slogan regarding the trial

they were expected to conduct. To assess semantic and syntactic clarity, expert

judges used a four-point likert scale where 1 indicated "different",

2 "quite different" 3, "pretty similar" and 4

"identical", this referred to whether the reagent was easily

understood, in our cultural context. On the other hand, to assess the

consistency of translations, expert judges used a four-point likert scale where

1 indicated "does not meet the criterion", 2 "low

level" 3, "moderate level" and 4 "high level", this referred to thus the reagent makes sense with respect to the

dimension or indicator it is measuring. Finally, to assess the relevance of

translations, expert judges used a four-point likert scale where 1 indicated

"does not meet the criterion", 2 "low level"

3, "moderate level" and 4 "high level", this referred to thus the reagent was essential or very important and

should be excluded.

Through these scales, each expert

responded by reading the item from the original version and then scored each of

the three translations establishing the semantic equivalence, coherence and

relevance of the items. according to the recommendations of Tornimbeni et al. (2008). In this way, the final version was made

up of the items that obtained the highest score by the judges. In turn, an

observations section was established, instructing the judge to make

observations regarding the congruence of the item with the dimension and syntactic

aspects that he wanted to highlight.

Once the results of each

of the judges were obtained, a form was made with all the valuations from which

the percentage of agreement was estimated (Tinsley and Weiss, 1975) and the

coefficient V of Aiken (Aiken, 1985) of the trial carried out by all judges.

These agreement indicators are represented by values ranging from 0 to 1 the

closer to 1 the reagent will have greater content validity.

Second, according to the

recommendations of Hogan (2004), a discrimination analysis of the items was

carried out, providing information on the ability of an item to differentiate

in statistical terms the individuals who have a higher value of the variable of

those who have a lower level. The internal method of comparison between

extremes was used (Muñiz, 2005), dividing the sample into quartiles with

respect to the total score obtained. Once this was done, a comparison was made

of the values of each item in the two groups –quartile 1 and quartile 4-,

thus determining which items discriminate adequately. To do this, the Mann

Whitney U statistic was used, since the items did not fulfill the assumption of

normality.

Third, the structural

validity of the BAI was evaluated. For this, three models disseminated in the

literature were tested: the one-factor (Magán et al., 2008), the original

two-factor (Beck et al., 1988), and the four-factor (Osman et al., 1993).

Because the data did not meet the normality criteria and the response format of

the BAI, following the criteria adopted by Osman et al. (1997), an analysis of

the covariance matrices was carried out using the elliptical test with

reweighted least squares (Browne, 1984) with the EQS version 6.1 statistical

software.

The following goodness

of fit indices were considered: x2 divided by the degrees of freedom

(values ≤ 5.0 indicate a good fit); NNFI (Non-Normed Fit Index); CFI

(Comparative Fit Index), RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation) and

SRMR (Standardized Root Mean-Square Residual). According to the criteria

specified by Kline (2011) and Schumacker & Lomax (2016), values greater

than or equal to .90 in NNFI and CFI and values less than or equal to .06 in

RMSEA and less than .08 in RMSEA and less than .08 in SRMR. In turn, the AIC

(Akaike's Information Criterion) was taken into account, which yields relative

values. The best model will be the one with the lowest AIC. The construct

validity was evaluated by examining the factor loadings. Values above .30

were considered adequate (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994).

Finally, to assess

internal consistency, the α ordinal and ω ordinal reliability

indices were calculated (McDonald, 1999), from polychoric correlation matrices.

For this, the R program version 3.6.0 and the following R packages were used:

GPArotation (Bernaards, & Jennrich, 2005), psych (Revelle, 2018) and Rcmdr

(Fox, & Bouchet-Valat, 2019). The composite reliability coefficient ρ (Bentler, 1968) was

also reported, based on the standardized loads of the items that make up the

inventory. In turn, the corrected item-factor correlations were calculated,

considering as adequate values greater than .40. (Nunnally & Bernstein,

1994).

To establish normative

values, percentile scores were calculated with the SPSS version 26 software, in

accordance with the recommendations of Sanz (2014).

Ethical aspects

The purpose of the

study was explained in writing before administration began. All participants

gave their consent. Informed consent set out the characteristics of the

participation, which was anonymous, voluntary and uncompensated. At the end of

the administration, participants were provided with the document containing the

recommendations to face the pandemic, published by the Faculty of Psychology of

the University of Buenos Aires (2020).

RESULTS

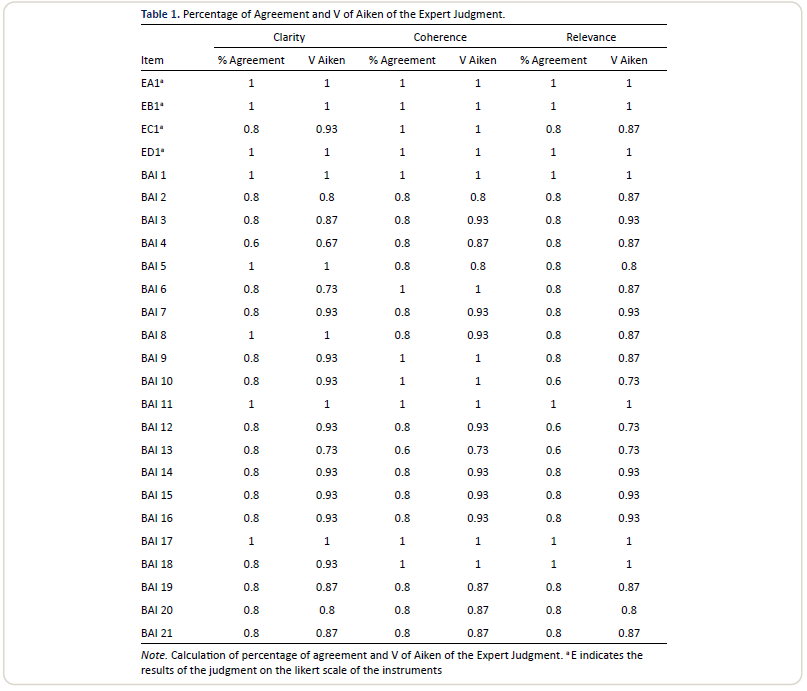

To obtain evidence of

content validity, the expert judgment was conducted. From the three

translations and the indications of the five judges, the 21 items were

selected. Regarding the three established criteria -Semantic equivalence, coherence and relevance- the

items that made up the final version, obtained percentages of agreement between

.80 and 1, adequate according to the literature (Voutilainen & Liukkonen,

1995, cited in Hyrkäs et al., 2003) with the exception of item 4 -Unable to

relax- whose semantic clarity index was below .80, its translation was

“Inability to relax”. In this particular item, one of the judges questioned

whether it was written in the first person. Based on this observation, it was

decided to modify the item so that the final version ended up being

"Inability to relax."

In turn, Aiken's V

coefficients ranged between values of .80 to1 mostly, acceptable values

according to the literature (Aiken, 2003). However, items 4, 6, 10 and 13

values were not adequate (see table 1). Regarding item 4, the modification

that was made based on the evaluations and observations has already been

indicated. In item 6 -Dizzy or lightheaded- whose final translation was

"Dizziness or vertigos" the translation brought difficulties due to

the low frequency of the words translated in our language, as no observations

were received from the judges, it was decided to consult a specialist in

linguistics from which it was decided to keep the aforementioned translation.

In relation to item 10 –Nervous- whose final translation was “Nervous”, as can

be seen in Table 1, the judges indicated disagreement regarding the relevance

of the item to assess anxiety symptoms, Due to the adaptation nature of the

present work, it was preferred to keep the item and evaluate its behavior at

the metric level. In turn, item 13 -Shaky / unsteady- whose translation was

“Restless / insecure” presented inadequate values regarding its clarity and

relevance. Based on the observations received by the judges, it was decided to

replace the word insecure with shaky, defining the final version of the item as

“Inquiero / shaky”. Finally, two of the expert judges reported that the DSM 5

(American Psychological Association, 2013) made a modification in the diagnosis

of panic disorder and the criterion "Fades or fainting" was modified

by "Feeling fainting or fainting" understanding that the test was

built under an earlier version of the DSM taking as a criterion that symptom

was decided to modify it by translating item 19 as Feeling of fading or

fainting.

In

conclusion, the expert trial has provided valuable results in relation to the

analysis and modification of direct translations by bilingual judges in such a

way that certain inconsistencies that were corrected or in some cases will be

taken into account in subsequent reagent analyses have been detected.

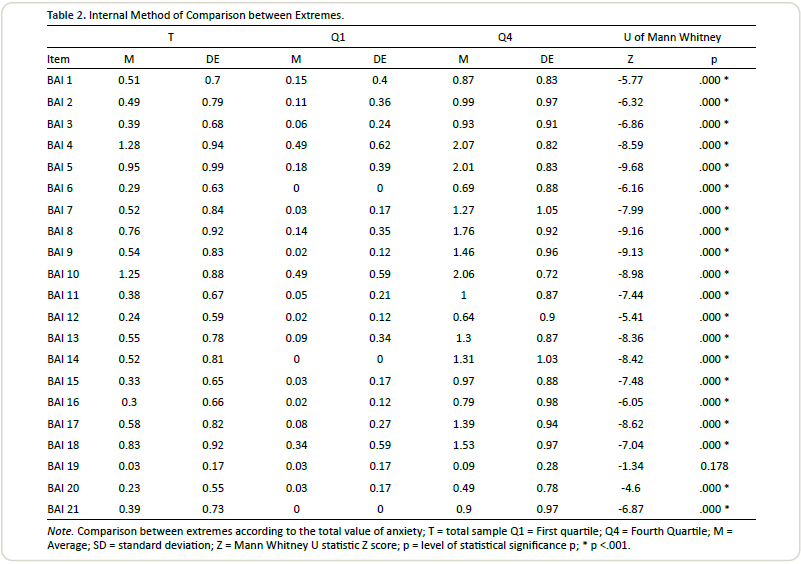

Regarding the analysis of the reagents,

Table 2 shows the results of the comparison of the items according to quartile

1 and quartile 4 obtained by the total score of each case. The differences were

significant in all cases p <.01 (α = .01), with the exception of item 19, this would

indicate that all of them discriminate adequately. Regarding item 19 - Feeling

of fainting or fainting - it should be noted that it only obtained responses of

1 and 2 points on the Likert scale in the entire sample. It is probable that

although the discrimination power of item 19 was not adequate, it has a

clinical utility at a qualitative level, for this reason, it was decided to

keep it and evaluate it from the confirmatory factor analysis carried out.

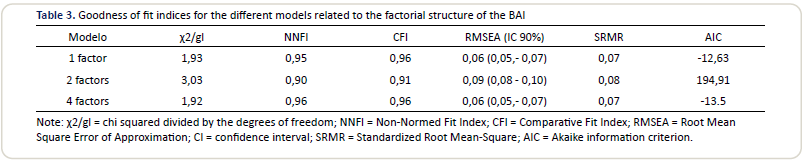

To examine the factorial structure, 3

models were tested: the one-factor, the original two-factor and the four-factor

models, through a confirmatory factor analysis performed from the analysis of

the covariance matrices using the elliptical test with minimums. reweighted

squares.

Regarding the single factor model, the

goodness of fit indices were the following: χ2 (184) =

355.37; CFI = 0.96; NNFI = 0.95; RMSEA = 0.06; SRMR = 0.07; AIC = -12.63.

Regarding the two-factor model, the goodness of fit indices obtained were: χ2 (188) = 570.91; CFI = 0.91; NNFI = 0.90; RMSEA = 0.09; SRMR = 0.08;

AIC = -194.91. In relation to the four-factor model, the following goodness of

fit indices were obtained: χ2 (183) = 352.96; CFI = 0.96; NNFI = 0.96;

RMSEA = 0.06; SRMR = 0.07; AIC = -13.05 (Table 3). These results indicate that

the most suitable model is that of a factor.

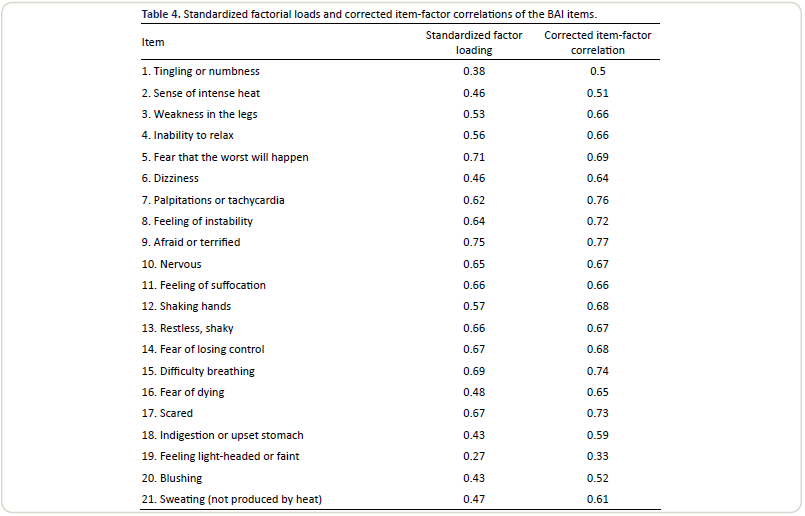

Regarding the construct validity, the

standardized factor loadings, scores greater than> .40 were obtained in all

cases except for item 19: “feeling of fainting or fainting”, whose standardized

load was 0.27 (Table 4).

In relation to internal consistency,

ordinal alpha and omega were calculated for the only factor that makes up the

entire inventory. Α ordinal = 0.93, ω ordinal =

0.95 were obtained. Regarding the composite reliability, ρ = 0.92 was obtained. The corrected item-factor correlations have been

obtained satisfactory values for all items except for item 27 (Table 4).

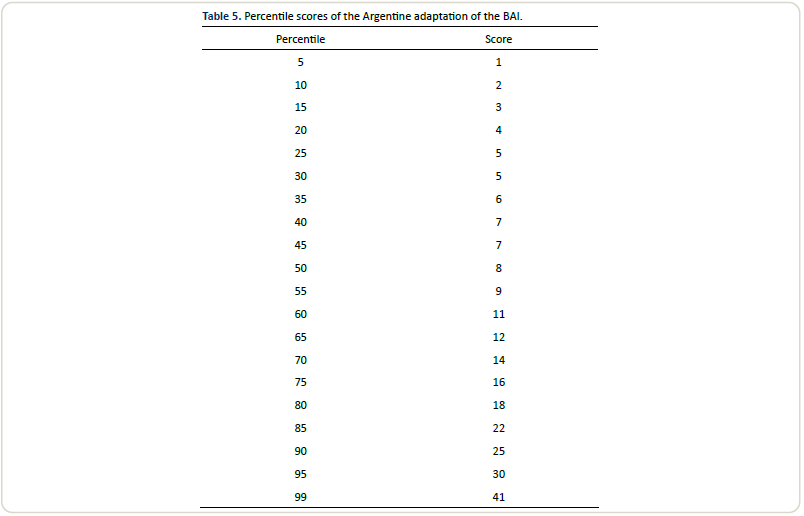

In relation to the formulation of

normative values, Table 5 provides percentile scores for the scores of the

Argentine adaptation of the BAI.

DISCUSSION

The general objective

of this research was to carry out the conceptual, linguistic and metric

adaptation of the Beck Anxiety Inventory in the general adult population of

Buenos Aires. The specific objectives proposed were a) to examine evidence of

content validity; b) analyze the discrimination capacity of the items; c)

obtain evidence of structural and construct validity; d) study the internal

consistency of scores; 3) establish normative values.

Following the

recommendations of Muñiz et al. (2013), it was decided to carry out a direct

translation of the questionnaire, the expert judges evaluated the semantic and

syntactic clarity of the adapted version. The process provided relevant

information to correct linguistic aspects in some cases –item 4- and cultural

ones where words more representative of the symptomatology in our culture were

used –items 6 and 13-. In turn, a modification was made to item 19 based on the

change produced in DSM 5. In the new version of the manual it is reported that

the diagnostic criteria for panic disorder, fainting, and dizziness are related

to the perception of loss of consciousness. control or death and it was

specified that the criterion should contemplate the sensation since it is

typical of the disorder that the person perceives that sensation and it does

not always become concrete (American Psychological Association, 2013). Due to

the aforementioned, item 19 "Fainting or fainting spells" was

modified for "Feeling of fainting or dizzy". The aforementioned

changes account for a translation process that included the updating and the

context of application of the instrument. On the other hand, the acceptable

values of percentage of agreement and V of Aiken in the relevance dimension,

evaluated by the expert judges, show that the adapted version presents adequate

content validity. In turn, the reliability coefficients that in all cases

exceed .90 provide greater evidence of the internal consistency presented by

the questionnaire. This indicates that the items are a representative sample of

the anxiety symptoms that the questionnaire intends to measure. However, item

10 has been questioned by the judges regarding the relevance to assess anxiety

symptoms, however, both the comparison test between extremes (which shows an

adequate discrimination power of the item) and the CFA where the item has a

high factorial load, show its relevance in the test. It would be appropriate to

evaluate the aforementioned items in tests of convergent and discriminant

validity.

On the other hand, with

the exception of item 19, the items have shown adequate discrimination power in

all cases, from separating the sample into quartiles based on the total score,

it was evidenced that the items discriminate adequately between those with

major and minor anxiety symptoms. Regarding item 19, as mentioned above, as it

is a specific item for panic disorder, it should be studied in a clinical

population in order to evaluate its discrimination power according to anxiety

disorder.

Regarding structural

validity, although the three models studied obtained adequate goodness-of-fit

indices, it was found that the best model is one factor. This result coincides

with the research of Magán et al., 2008, who when they adapted the instrument

in the Spanish population and found that the most appropriate solution was a

global anxiety factor. In this sense, the results are not coincident with the

original two-factor structure (Beck et al., 1988). In that sense, Bardhoshi, Duncan & Erford (2016), in a psychometric meta-analysis

on the properties of the English versions of the BAI, found that studies have

reported solutions of 1 to 6 factors. In such a way that population

peculiarities could affect the factorial structure of the instrument.

When analyzing the standardized loadings of the items, satisfactory

values were found in all cases, except again in item 19, "Feeling of

fainting or fainting." This result can be explained because the item

refers to a specific diagnostic criterion only for panic disorder for DSM 5. It is important to

clarify that other anxiety disorders can lead to panic episodes, which justifies

keeping the item as a relevant qualitative indicator is highlighted in the

final version of the Argentine adaptation of the inventory. However, it is recommended to analyze the psychometric properties of the inventory

in larger samples, as well as in the clinical population to reevaluate its

functioning.

Taking into account the fourth objective to study the internal

consistency of the scores, excellent values were obtained in the three

calculated indexes, according to the criterion established by George &

Mallery (2003): Ordinal α =0,93, ordinal ω = 0,95, and composite reliability

ρ=0,92.

Regarding the last objective, namely

establishing normative values, percentile scores obtained from the application

of the BAI are offered. Although these normative values can be indicative in

relation to the global level of anxiety, it is suggested to interpret them

carefully and take them as tentative. Given the small sample size and the

non-representativeness of the sample.

To conclude, the Argentine adaptation of

the Beck Anxiety Inventory is a valid and reliable instrument for the

evaluation of anxiety symptoms in adults in Buenos Aires. As it is a short and

easy-to-administer instrument, it is considered very useful for carrying out

follow-up tasks in the current context, as well as for evaluating

psychotherapeutic interventions.

Regarding the limitations of the study

carried out, first of all the small size and non-probabilistic nature of the

sample collected can be mentioned. Future research may take larger and more

representative samples, as well as from different regions of the country, to

have a global vision about the phenomenon of interest.

Secondly, even with the evidence obtained,

new studies are required to analyze factor constancy through different samples,

as well as convergent and discriminant validity. Specifically, to study the

discriminative power of BAI in relation to depressive symptoms.

Third, it is suggested that later studies

investigate invariance of different sociodemographic variables such as gender

or age, to ensure that the factorial structure is constant in different groups.

ORCID

Nicolas Alejandro

Vizioli https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6113-6847

Alexander Emilio

Paganohttps://orcid.org/0000-0003-4817-9145

AUTHORS

'CONTRIBUTION

Nicolás Alejandro Vizioli: Conceptualization, methodology, software,

validation, formal analysis, research, writing - original draft,

writing-review, visualization.

Alejandro Emilio Pagano: Conceptualization, methodology, software,

validation, formal analysis, data curation, writing - original draft,

visualization.

FUNDING

Self-funded research.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Does not apply.

REVIEW

PROCESS

This study has been peer-reviewed in a

double-blind manner.

DECLARATION

OF DATA AVAILABILITY

The authors express our support for open

science. However, we consider it relevant to safeguard the database to preserve

the anonymity of the participants and the confidentiality of the data, in

relation to professional secrecy. The database, as well as the instrument, may

be requested from the authors' emails.

DISCLAIMER

The authors are responsible

for all statements made in this article. Neither Interactions nor the Peruvian

Institute of Psychological Orientation are responsible for the statements made

in this document.

REFERENCES

Aiken,

L. R. (2003). Tests psicológicos y evaluación. Pearson educación.

Aiken, L. R. (1985).

Three coefficients for analyzing the reliability and validity of ratings [Tres

coeficientes para analizar la confiabilidad y validez de las calificaciones]. Educational and psychological measurement, 45(1), 131-142.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164485451012

Aldao, A.,

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Schweizer, S. (2010). Emotion-regulation strategies

across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical psychology review, 30(2), 217-237.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004

Alonso, J. et al (2018).

Treatment gap for anxiety disorders is global: Results of the World Mental

Health Surveys in 21 countries. Depression and anxiety, 35(3), 195-208. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22711

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental

disorders (DSM-4®). Author.

American Psychiatric

Association. (2013). Diagnostic and

statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Pub.

Andreani, O. (1975). Aptitud Mental y Rendimiento Escolar. Herder.

Bardhoshi, G., Duncan, K., & Erford, B. T. (2016). Psychometric

meta‐analysis of the English version of the Beck Anxiety Inventory. Journal of Counseling & Development,

94(3), 356-373. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12090

Barlow, D. H., Farchione, T. J., Fairholme, C. P., Ellard, K. K.,

Boisseau, C. L., Allen, L. B., & Ehrenreich-May, J. (2016). Protocolo unificado para el tratamiento transdiagnóstico de

los trastornos emocionales. Alianza Editorial.

Beck, A. T., Epstein, N., Brown, G., & Steer, R. A. (1988). An inventory for measuring

clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties [Un inventario para medir la ansiedad

clínica: propiedades psicométricas]. Journal

of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56(6),

893–897. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.56.6.893

Bentler, P. M. (1968).

Alpha-maximized factor analysis (alphamax): Its

relation to alpha and

canonical factor analysis. Psychometrika,

33,

335–345.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02289328

Bentler, P. M. (1990).

Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological bulletin, 107(2), 238. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238

Bernaards, C. A., &

Jennrich, R. I. (2005). Gradient projection algorithms and software for

arbitrary rotation criteria in factor analysis. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 65, 676-696.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164404272507

Brown, T. A. (2006). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied

research. Guilford publications.

Browne, M. W. (1984).

Asymptotically distribution‐free methods for the analysis of covariance

structures. British journal of

mathematical and statistical psychology, 37(1), 62-83.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8317.1984.tb00789.x

Clark, D. A., & Beck,

A. T. (2011). Cognitive therapy of

anxiety disorders: Science and practice. Guilford Press.

Escobar-Pérez, J., y

Cuervo-Martínez, Á. (2008). Validez de

contenido y juicio de expertos: una aproximación a su utilización. Avances

en medición, 6(1), 27-36. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Jazmine_Escobar-Perez/publication/302438451_Validez_de_contenido_y_juicio_de_expertos_Una_aproximacion_a_su_utilizacion/links/59a8daecaca27202ed5f593a/Validez-de-contenido-y-juicio-de-expertos-Una-aproximacion-a-su-utilizacion.pdf

Evans, J. D. (1996). Straightforward statistics for the

behavioral sciences. Brooks/Cole Publishing

Facultad de Psicología de la Universidad

de Buenos Aires (2020). Recomendaciones psicológicas para afrontar la

pandemia. Autor.

http://www.psi.uba.ar/institucional/agenda/covid_19/recomendaciones_psicologicas.pdf

Fox, J., &

Bouchet-Valat, M. (2019). Rcmdr: R

Commander. R package version 2.5-2.

https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/Rcmdr/index.html

George, D., &

Mallery, P. (2003). SPSS for Windows step

by step: A simple guide and reference. 11.0 update (4th ed.). Allyn &

Bacon.

Gorman, J. M. (1996).

Comorbid depression and anxiety spectrum disorders. Depression and anxiety, 4(4), 160-168.

https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6394(1996)4:4%3C160::AID-DA2%3E3.0.CO;2-J

Hogan, T. (2004). Pruebas Psicológicas. El Manual Moderno. Mc Graw Hill

Hyrkäs, K.,

Appelqvist-Schmidlechner, K., y Oksa, L. (2003). Validating an instrument for clinical

supervision using an expert panel [Validación de un instrumento para la

supervisión clínica mediante un panel de expertos]. International Journal of

nursing studies, 40(6), 619-625.

Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural

equation modeling. Guilford Press.

Lépine, J. P. (2002). The

epidemiology of anxiety disorders: prevalence and societal costs. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 63,

4.

Magán, I., Sanz, J.,

& García-Vera, M. P. (2008). Psychometric properties of a Spanish version

of the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) in general population. The Spanish journal of psychology, 11(2), 626.

https://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/SJOP/article/download/SJOP0808220626A/28750/0

McDonald, R.P. (1999). Test theory: A unified treatment.

Erlbaum.

Mineka, S., Watson, D.,

& Clark, L. A. (1998). Comorbidity of anxiety and unipolar mood disorders. Annual review of psychology, 49(1),

377-412. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.377

Mountjoy, C. Q., &

Roth, M. (1982). Studies in the relationship between depressive disorders and

anxiety states: Part 2. Clinical items. Journal

of affective disorders, 4(2), 149-161.

https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-0327(82)90044-1

Muñiz, J. (2005). Análisis de los ítems. Editorial la Muralla.

Muñiz, J., Elosua, P., y Hambleton, R. K. (2013). Directrices

para la traducción y adaptación de los tests: segunda edición. Psicothema, 25(2),

151-157. https://www.unioviedo.net/reunido/index.php/PST/article/view/9910.

Nunnally, J. C., &

Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric

theory (3rd ed.). McGraw Hill.

Osman, A., Barrios, F.

X., Aukes, D., Osman, J. R., & Markway, K. (1993). The Beck Anxiety

Inventory: Psychometric properties in a community population. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment,

15(4), 287-297. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00965034

Osman, A., Kopper, B. A.,

Barrios, F. X., Osman, J. R., & Wade, T. (1997). The Beck Anxiety

Inventory: Reexamination of factor structure and psychometric properties. Journal of clinical psychology, 53(1),

7-14.

https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(199701)53:1%3C7::AID-JCLP2%3E3.0.CO;2-S

Piotrowski, C. (2018).

The status of the Beck inventories (BDI, BAI) in psychology training and

practice: A major shift in clinical acceptance. Journal of Applied Biobehavioral Research, 23(3), e12112.

https://doi.org/10.1111/jabr.12112

Rajkumar, R. P. (2020).

COVID-19 and mental health: A review of the existing literature. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 102066.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102066

Revelle, W. (2018). Psych: Procedures for psychological,

psychometric, and personality research. R package version 1.8.12.

https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/psych/index.html

Ritchie, H., & Roser,

M. (2018). Mental Health. Our World in

Data. https://ourworldindata.org/mental-health

Ruiz-Rodríguez, P. et al (2017). Impacto económico y carga de

los trastornos mentales comunes en España: una revisión sistemática y crítica.

Ansiedad y Estres, 23(2-3), 118-123.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anyes.2017.10.003

Sanz, J. (2014). Recomendaciones para la utilización de la

adaptación española del Inventario de Ansiedad de Beck (BAI) en la práctica

clínica. Clínica y Salud, 25(1),

39-48. http://scielo.isciii.es/pdf/clinsa/v25n1/original4.pdf

Sanz, J., & Navarro, M. E. (2003). Propiedades

psicométricas de una versión española del inventario de ansiedad de beck (BAI)

en estudiantes universitarios [The psychometric properties of a spanish version

of the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) in a university students sample]. Ansiedad y Estrés, 9(1), 59–84.

Schumacker, R., &

Lomax, R. (2016). A beginner´s guide to

structural equation modeling. Routledge.

Stagnaro, J. C. et al (2017). Estudio epidemiológico de salud

mental en población general de la República Argentina. Vertex, 275. http://www.editorialpolemos.com.ar/docs/vertex/vertex142.pdf#page=36

Tinsley, H. E., y Weiss, D. J. (1975). Interrater reliability

and agreement of subjective judgments [Fiabilidad entre evaluadores y acuerdo

de juicios subjetivos]. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 22(4), 358.

Tornimbeni, S., Pérez,

E., Olaz, F., de Kohan, N. C., Fernández, A., y Cupani, M. (2008). Introducción a la psicometría. Paidós.