http://dx.doi.org/10.24016/2020.v6n3.162

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Risk eating behaviors, perception of parental practices and assertive

behaviors in high school students

Conductas alimentarias de riesgo, percepción de prácticas parentales y

conducta asertiva en estudiantes de preparatoria

María Leticia

Bautista-Díaz 1 *, Ariana Ibeth Castelán-Olivares 2, Armando

Martin-Tovar 2, Karina Franco-Paredes 3 y Juan Manuel Mancilla-Díaz 4

1 Carrera de Psicología, Grupo de

Investigación en Aprendizaje Humano, Facultad de Estudios Superiores Iztacala,

Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México.

2 Instituto de Ciencias de la Salud,

Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo, México.

3 Centro de

Investigación en Riesgos y Calidad de Vida, Universidad de Guadalajara, México.

4 Grupo de Investigación en Nutrición,

Facultad de Estudios Superiores Iztacala, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de

México, México.

*

Correspondence: Iztacala School of Higher Studies, National Autonomous

University of Mexico. Avenida de los Barrios # 1, Los Reyes Iztacala, Tlalnepantla, Edo.

Mex. CP 54090, AP 314, Mexico. e-mail:psile_7@yahoo.com.mx; psile_7@unam.mx. Telephone: +55

9188 0791.

Received:May 03, 2020 | Revised: July 19, 2020 | Accepted: August 02, 2020 |

Published Online: September 14, 2020.

CITE

IT AS:

Bautista-Díaz, M., Castelán-Olivares, A., Martin-Tovar, A.,

Franco-Paredes, K., & Mancilla-Díaz, J. (2020). Risky eating behaviors, perception of parenting

practices and assertive behavior in high school students. Interacciones, 6(3), e162.https://doi.org/10.24016/2020.v6n3.162

ABSTRACT

Background: Late adolescence is considered a risk stage for psychological health.

The objective of this research was evaluating the association among risk eating

behaviors (REB), parental practices and assertive behavior in high school

students according to sex. Method: With

a non-experimental design and transversal study participated 200 students (104

men and 96 women) from a public high school with age mean of 16.52 (SD = 1.05 years), who after signing

informed consent fulfilled the Eating Attitudes Test-26 (EAT), the Scale of

Parental Practices for Adolescents (PP-A) which has nine subscales, four

towards the father (PPf) and five towards the mother (PPm) and the Assertive

Behavior Scale (CABS), all of them validated for Mexican population. Results: Differential associations were

found according to sex: in women, EAT-26-Total was associated with CABS-Total,

parental Communication, maternal Imposition and maternal Psychological Control

(rs = -.36, .25, -.28,

-.36, respectively); but in men, was only associated with parental Imposition (rs = -.30). The CABS-Total

was associated with all PPm subscales in women (range rs = .22 to .36) and in men only with Communication,

Psychological and Behavioral Control (rs

= .30 .35, -.23). Conclusion: The

high school students –women to a greater degree– higher REB greater aggressive

style (no assertiveness), greater maternal psychological control and less

maternal behavioral control.

Keywords: Eating disorders; assertiveness;

parenting; adolescence; mental health.

RESUMEN

Introducción: Se

considera que la adolescencia tardía es una etapa de vulnerabilidad para la

salud psicológica. El objetivo de esta investigación fue evaluar la asociación

entre conductas alimentarias de riesgo (CAR), prácticas parentales y conducta

asertiva en estudiantes de preparatoria de acuerdo con el sexo. Método: Con un diseño no-experimental

de tipo transversal, participaron 200 estudiantes mexicanos (104 hombres y 96

mujeres) de una preparatoria pública, con edad promedio de 16.52 (DE = 1.05 años), quienes después de un

consentimiento informado contestaron el Test de Actitudes Alimentarias-26 (EAT,

por sus siglas en inglés), la Escala de Prácticas Parentales para Adolescentes

(PP-A) la cual posee nueve subescalas, cuatro hacia el padre (PPp) y cinco

hacia la madre (PPm) y la Escala de Conducta Asertiva (CABS, por sus siglas en

inglés), todos validados para población mexicana. Resultados: Se encontraron asociaciones diferenciales de acuerdo

con el sexo: en las mujeres el EAT-26-Total se asoció con: CABS-Total, Comunicación

paterna, Imposición y Control Psicológico materno (rs = -.36, .25, -.28, -.36, respectivamente); mientras

que, en los hombres sólo se asoció con Imposición paterna (rs = -.30). El CABS-Total se asoció con todas las

subescalas de las PPm en las mujeres (rango rs

= .22 a .36) y en los hombres solo con Comunicación, Control Psicológico y

Conductual (rs = .30 .35,

-.23). Conclusión: En los

estudiantes mexicanos de preparatoria –en las mujeres en mayor grado– a mayor

CAR mayor estilo agresivo (no asertividad), mayor control psicológico materno y

menor control conductual materno.

Palabras clave: Trastornos de la conducta alimentaria; asertividad; parentalidad;

adolescentes; salud mental.

BACKGROUND

In the biological dimension of any living

being, food is one of the most important basic needs of human beings, since

survival depends on it (González, Plasencia, Jiménez, Martín, & González,

2008; Martínez, & Pedrón, 2016). Regarding the psychosocial dimension of

food in human beings, affective, cognitive and behavioral aspects are involved,

it also represents a central point of socialization (Fleta & Sarría 2012;

Marmo, 2014; Musitu, Buelga, Lila, & Cava 2001; Ngo de la Cruz, 2012; Peña

& Reidl, 2015). In

this regard, when eating has significant alterations based on cognitions or

behavior, either with decreased or increased food intake to control body

weight, risky eating behaviors (CAR) arise and in extreme cases of frequency,

intensity and morphology of CAR can lead to disorders of eating behavior (TCA;

American Association of Psychology [APA], 2013; Bermúdez, Machado, &

García, 2016; Contreras et al., 20015; Cortez et al., 2016).

CARs are a complex entity because

biological and psychosocial factors intervene in their development or

maintenance with devastating consequences that can lead to significant damage

such as medical or psychiatric comorbidity and sometimes serious, even suicide,

for this reason it is a field of study from health psychology as it is not only

an individual problem but represents a national and international public health

issue that has gained importance mainly in women, but increasingly, cases of

men with these psychopathologies are reported (Gonçalves, Machado, & Machado,

2011; López &

Treasure, 2011; Martínez, Vianchá, Pérez, & Avendaño, 2017; Skemp, Elwood,

& Reineke, 2019).

At least five CARs linked to remedying

body weight are recognized: 1) excessive food intake (binge eating), 2)

inappropriate use of diuretics and / or laxatives (purging), 3) regular

practice of restrictive diets, 4) prolonged fasting or frequent and 5)

self-induced vomiting (Ortega-Luyando et al., 2015; Unikel, Díaz de León, &

Rivera, 2016). Some studies show that CARs can appear primarily at an early

age, however, it is in adolescence where this health problem prevails to a

greater extent (Gutiérrez et al., 2012; López

& Treasure, 2011; Miranda, 2012; Ortega et al, 2015;

Radilla et al., 2015). This can be explained, because it is known that

adolescence is characterized by various physical, cognitive and psychosocial

changes, which usually determine the actions of individuals in different social

contexts (Berger, 2016; Papalia, Feldman, & Matorrel, 2017); Therefore,

early, middle or late adolescence is considered to be a stage of vulnerability

to carry out behaviors that affect the physical and psychological health of

this population, such is the specific case of CAR, or other psychological

disorders (Campell & Peebles, 2014; Radilla et al., 2015; World Health

Organization [WHO], 2019).

Despite the large body of research

regarding CARs, data on its etiology or maintenance are still inconclusive. For

example, it has been suggested that the perception of parental practices,

understood as those beliefs, attitudes and behaviors that parents exercise over

their children, with the purpose of influencing, educating and guiding their

children for their social and emotional development, can have a negative effect

on various spheres of their patrons (Matalinares-Calvet et al., 2019;

Ruvalcaba-Romero, Gallegos-Guajardo, Caballo, & Villegas-Guinea, 2016).

That is whyEU, when the

interaction dynamics are not adequate, they could lead to the development of

CAR, (Espinoza, Ochoa de

Alda Martínez, & Ortego, 2007; Guttman & Laporte, 2002; Marmo, 2014;

Sánchez, Villarreal, & Musitu, 2010). On the contrary, it has been shown

that the family role around food is a protective factor against binge-purging

behavior (Valero, Granero, & Sánchez-Carracedo, 2019). However, it has also

been reported that there is no significant association between parenting

practices and CAR (Espina et al., 2007).

Some studies have shown that children's eating habits are the mirror of

their parents, since they adopt certain eating practices that can be negative,

such as those related to weight control, specifically, restrictive diets or

prolonged fasts, among Others, which if they occur with certain regularity and

intensity, can trigger patterns that escape the control or will of the children

and eventually develop CAR or TCA (Castrillón & Giraldo, 2014; Ventura

& Birch, 2008; Losada , 2018).

On the other hand, regarding the study of

social skills (HHSS) in adolescence, it is relevant due to the search for

identity that characterizes this population, these - despite the lack of

consensus in their conceptualization - are have defined as a set of social

skills emitted by the individual, which arise from feelings, attitudes and

emotions in certain situations and in certain contexts (Caballo, 2005; Caballo,

Salazar, Irurtia, Olivares, & Olivares, 2014); such social skills are

essential for appropriate interpersonal relationships, not only between peers,

but with people of legal age or younger. In addition, helping adolescents

internalize social norms, so HHSS can be a protective factor for their

psychological health or, on the contrary, when they are inadequate can be a

risk factor for their well-being (Betina & Contini de González, 2011;

Horse, Salazar, & Research Team, CISO-A Spain, 2018).

Because adolescents face various environmental demands, they often make

use of the psychological resources found in their behavioral repertoire,

putting into practice a fundamental component of the HHSS on a daily basis,

such is the case of the assertive behavioral social style or not assertive. The first is the most appropriate style of social behavior, because their actions show good social competence, so that an adolescent with an assertive style respects the rights of others and defends their own, thinks before he acts, values the pros and cons of situations and his own behavior (Caballo et al., 2014; De la Peña, Hernández, & Rodríguez, 2003; León & Vargas, 2009).

While, the second (not assertive), involves two subtypes; 1) passive,

which is characterized by not possessing social competence, therefore, it is an

obstruction in the development or maintenance of interpersonal relationships,

as well as in their own feelings since they tend to repress their way of

thinking and feel, this type of social ability, some researchers have called

inhibited style (Corrales, Quijano, & Góngora, 2017; De la Peña et al., 2003; Naranjo, 2008); and 2) aggressive

style, which is also regarded as inadequate social prowess, because people with

this kind of social behavior do not take into account the rights of others,

putting their own desires above others, regardless of the harm it may cause.

In summary, CAR, parenting practices and

assertive-non-assertive behavior can play an important role in the present and

future psychological health of high school students because they are in a

vulnerable stage, however, it is of knowledge of the authors that these

variables as a whole have received little attention, therefore, the objective

of this research was to evaluate the association between risky eating

behaviors, parenting practices and assertive behavior according to sex in

students of upper secondary education.

Research hypothesis: There is a statistically significant association

between Risky eating

behaviors, parenting practices, and assertive behavior in high school students

according to gender.

METHODS

Design

In the present

investigation, only the variables were evaluated at a given moment and there

was no deliberate manipulation of the variables, so the design is

non-experimental and cross-sectional. In terms of its scope, it is

correlational (Coolican, 2005; García et al., 2014; Ríos, 2017).

Participants

Through a

non-probabilistic sampling by availability (Universe), 200 students

participated (104 men [52%] and 96 women [48%]) from a public high school in

the State of Hidalgo, Mexico, with an average age of 16.52 (SD = 1.05, years)

and a range between 15 and 19 years.

Instruments

Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-26, for its acronym in English; Garner, Olmsted, Bohr, &

Garfinkel, 1982). Developed to assess risk eating attitudes and behaviors,

through 26 items with a Likert-type response option, which has three subscales:

1) Diet; 2) Bulimia and preoccupation with food; 3) Oral control and has a

cut-off point ≥ 20 which indicates a high risk of developing ED. The EAT-26 was

validated for the Mexican population by Franco, Solorzano, Díaz and

Hidalgo-Rasmussen (2016), a confirmatory factor analysis replicated the

original subscales and indicated high reliability (Alpha = .83). For this

research, an Alpha = .82 was obtained.

Parental Practices Scale for Adolescents (EPP-A) created and validated for the

Mexican population by Andrade and Betancourt (2010). It is made up of 80 items

with four Likert-type response options. It has two dimensions, one of these

assesses the perception of adolescents about the father's parental practices

(40 items) and consists of four subscales: 1) Communication and behavioral

control; 2) Paternal autonomy; 3) Paternal imposition and 4) Paternal

psychological control; while, the second dimension assesses the perception of

adolescents about the mother's parental practices (40 items) and consists of

five suebescales; 1) Maternal communication; 2) Maternal autonomy 3) Maternal

imposition; 4) Maternal psychological control; 5) Maternal behavioral control.

What the scales assess is briefly described below: Communication and behavioral

control, assesses the communication between the parent and the adolescent;

Autonomy, respect for the decisions of the children; Imposition, degree to

which parent / father impose beliefs and behaviors on the children;

Psychological control, the induction of guilt and excessive criticism towards

the children; Behavioral control assesses the knowledge about the daily

activities of the children. The two dimensions have good reliability, specifically

the one related to the father's parental practices has an Alpha of .88 with an

Alpha range between the subscales of .74 to .94; and that of the mother's

parental practices is .82, with an Alpha rank among its subscales from .66 to

.87. For the present investigation, adequate reliability was obtained for both

dimensions (PPm α = .82 and PPp α = .94), as well as for PPm subscales with an Alpha coefficient range

between .80 and .92) and PPp coefficients (Alpha between .94 and .96).

Assertive Behavior Scale for Children (CABS, for its acronym in English),

developed by Michelson and Wood (1982) with the objective of evaluating and

classifying the behavior of children and adolescents as assertive, passive or

aggressive. It consists of 27 questions with a Likert-type response option.

This scale was validated for the Mexican population by Lara and Silva (2002)

demonstrating adequate reliability (Alpha = .80) and for the classification of

social ability it derived the following cut-off points: 0-42 assertive: 43-50

passive; 51-135 aggressive. For the present investigation, a total reliability

of Alpha = .81 was obtained.

Process

Once the

investigation protocol was approved by the authorities of the institution of

assignment, the educational institution of upper secondary education was

contacted to present the protocol and request the necessary permits to carry

out the evaluation. Subsequently, in a group session the objective of the

research was explained, and they were invited to participate in the study, all

the parents present signed an informed consent and the students gave their

consent to be part of the study. In another 20-minute session, the participants

answered the battery of instruments inside the facilities of the educational

institution. At all times, trained personnel were present to resolve doubts and

avoid bias in the responses.

Analysis of data

Descriptive

analyzes were carried out, calculating the measures of central tendency and

dispersion. Because the data are not normally distributed: EAT-total

(Kolmogorov-Smirnov = 3.02, p = .001), CABS total (Kolmogorov-Smirnov = 1.40, p

= .04), and for the PPP subscales (range of p = .01-.04) non-parametric tests

were calculated; Thus, to assess the differences between sex, the Mann Whitney

U test was calculated. While, for the correlation analyzes between variables,

the Spearman Rho test was calculated. For both comparison and correlation, a

value of p <.05 was considered. Finally, to evaluate the effect size, the G

* Power program version 3.1 was used.

Ethical aspects

The present

observational research is considered without risk, because no intervention or

manipulation of variables was carried out, which was endorsed by the research

committee of the Autonomous University of the State of Hidalgo, for adhering to

the Code of Ethics of the Psychologist (Mexican Society of Psychology, 2010).

RESULTS

Sociodemographic descriptions

It was found that 56.3% of

the sample lives with both parents daily and 43.7% of the participants live

with their parents on the weekend since they move from their home to have access to an upper

secondary education, renting a room or living with a relative near the

educational institution; therefore, all participants have contact with both

parents. Thus, at the time of the evaluation it was found that, of the total

sample (n = 200), 112 (56.3%) participants lived with both parents, 66 (33.2%)

lived only with their mother, 14 (7.0%) with their mother. Dad and the

remaining percentage (3.5%) lived with another relative. Regarding occupation,

it was found that the majority of the sample, 164 (82.4%) only studied and 35

(17.6%) studied and carried out a paid activity.

Descriptive analysis of the risk of developing eating disorders

It was found

that 11 (5.5%) students exceeded the cut-off point (PC) of the EAT-26, with a

range of scores from 21 to 55, while the other 189 (94.5%) participants did not

represent a risk to develop eating disorders. Regarding the sex of those who

passed the CP of the EAT-26, seven (63.6%) are women and four (36.4%) are men.

When making the comparison between sex, regarding eating behavior, it was found

that there were no statistically significant differences between men and women

both in the EAT-26-Total, and in its subscales (Mann Whitney U; Z = 1.3, 1.1, 1.0,

1.4 respectively, p> .05).

Descriptive analysis of the perception of parenting practices

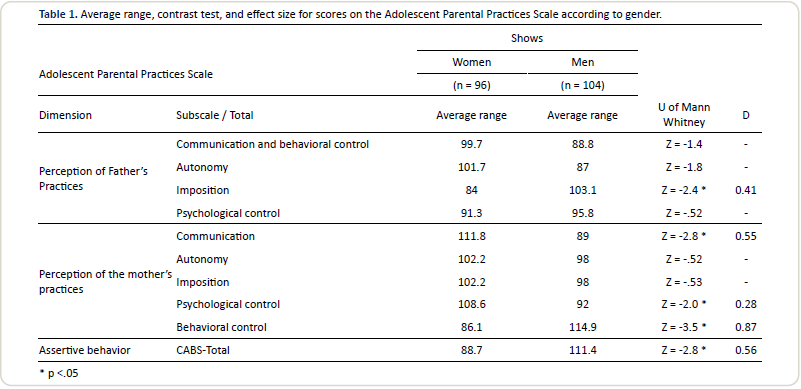

Regarding the perception of parental

practices, in Table 1, it can be observed that there are statistically significant

differences between men and women in the perception of: Parental imposition

with a higher average range in men (z=-.2.4, p < .05), with a recommended

minimum effect size for practical significance; Maternal communication

(z=-.2.8, p <.05), with a medium effect size; Maternal Psychological Control

(z = -.2.0, p <.05), with a minimum recommended effect size for practical

significance; and in Maternal Behavioral Control (z = -.3.5, p <.05), with a

large effect size, in these last three comparisons.

Descriptive analysis of assertive behavior

Regarding

assertive and non-assertive behavior evaluated with the CABS, a median = 53 and

a range width between (32 and 99) were found. According to the type of social

ability: 41 (20.5%) have an assertive style; 44 (22%) reported having a passive

style; and 115 (57.5%) participants are located in the aggressive type social

ability. Specifically, the participants who passed the CP of the EAT-26,

obtained in the CABS a mean of 67.3 (SD = 14.9), a median of 71, with a range

of scores between 51 and 99, therefore, they are located in the style

aggressive. While, in the comparison by sex, statistically significant

differences were found (Mann Whitney U; Z = -2.8, p <.05; d = .56), with a

higher average range in men compared to women (111.4 vs. 88.7, respectively)

and with a medium-effect size (see Table 1).

Correlations between the study variables of the total

sample

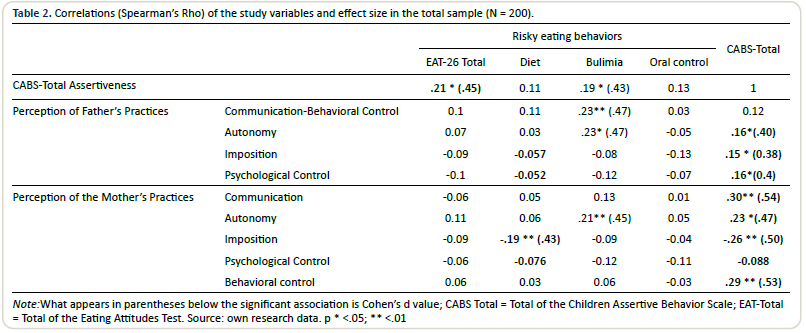

Table 2 shows

the associations between the study variables: EAT-26-Total and its three

subscales (Diet, Bulimia / Preoccupation with Food and Oral Control), with the

CABS-Total, as well as with the nine subscales of EPP-A (four towards the

father and five towards the mother) in the total sample. Regarding the association

between the EAT-26-Total and its subscales (total sample), it was only

significant and moderate with the CABS-total (rs=.21). Regarding the

three subscales of the EAT-26: Diet was weakly and negatively associated with

Imposition (paternal and maternal; rs = -.15, -.19, respectively)

and with Psychological Control (paternal and maternal; rs=- .14,

-.18, respectively); whereas, the Bulimia subscale was weakly and positively

associated with the CABS-total (rs=.19), as well as with Parental

Communication-Behavioral Control (rs=. 23) and with paternal and

maternal autonomy (rs=.23, .21, respectively). The effect sizes for

the significant associations ranged from weak to moderate. It should be noted

that Oral Control was not significantly associated with any of the study

variables.

Regarding the

CABS-Total, it was associated weakly and positively with paternal and maternal

autonomy (rs=.16, .23, respectively), but negatively with paternal

and maternal imposition (rs=-.15, -.26, respectively) , with paternal

and maternal Psychological Control (rs=-.16, -.20, respectively) and

positively with Father's Behavioral Control (rs=.29). The effect

sizes for the significant associations ranged from weak to moderate.

Correlations between the study variables according to

sex

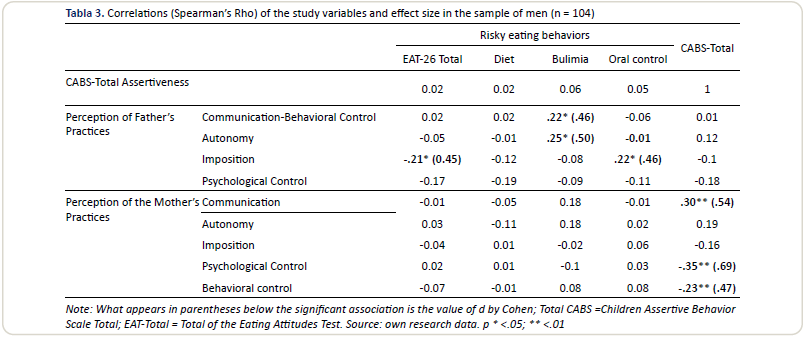

In order to

evaluate the association between the study variables according to sex, the

correlations were calculated independently for men and women. Table 3 shows the

associations for men and Table 4 for women. As can be seen, in the sample of

men, a lower number of significant associations was found compared to women (7

vs. 19, respectively). In the sample of men, the EAT-26-Total was only weakly

and negatively associated with paternal imposition (rs = -.21); the

Diet subscale was not significantly associated with any of the study variables;

while, the Bulimia subscale was weakly and positively associated with Parental

Communication and Autonomy (rs = .22, .25, respectively); Oral

control was only weakly and positively associated with paternal imposition (rs

= .22; see table 3). Regarding the CABS-Total, this presented

associations only with some of the variables of perception of the mother's

practices, associating positively with Communication and with Psychological

Control, but negatively with Behavioral Control (rs = .30, .35, and

-. 23, respectively). The effect sizes for the significant associations ranged

from weak to moderate.

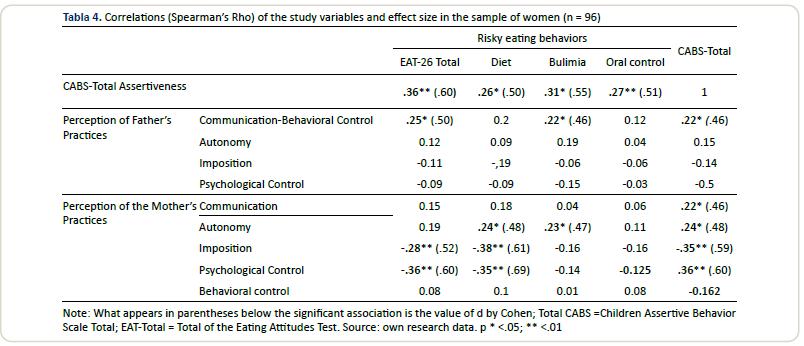

However,

regarding the associations in the sample of women, the EAT-26-Total was

moderately and positively associated with the CABS-Total (rs = .36);

with Paternal Communication (rs = .25) and with Maternal Imposition

and Psychological Control (rs = -.28, -.36, respectively). The Diet

subscale was weakly and positively associated with CABS-Total (rs =

.26) and with Autonomy, Imposition, but negatively with Maternal Imposition and

with Maternal Psychological Control (rs = .24, -.38, -.35,

respectively). While the Bulimia subscale was positively associated with CABS-Total

(rs = .31) and with Parental Communication-Behavioral Control (rs

= .22), as well as with Maternal Autonomy (rs = .23). Meanwhile,

Oral Control was positively associated with CABS-Total (rs = .27),

but negatively with maternal Psychological Control (rs = -.25).

Finally, the

CABS-Total was positively associated –with the same magnitude– with paternal

and maternal communication (rs = .22, respectively); Likewise, it

was associated with all the subscales of perception of maternal parental

practice: weakly and positively with Autonomy and Psychological Control (rs

=, 24 and .23, respectively), but negatively with Imposition and with

Psychological Control (rs = -. 35, -.34, respectively). Regarding

the size of the effect of the significant correlations, this was from weak to

moderate, all recommended of practical significance.

DISCUSSION

Even though it

was not objective to determine the presence of CAR due to the limited sample

size and specific type of population. It is important to highlight the low but

important percentage (5.5%) of male and female high school students who are at

risk for developing ED, due to the presence of CAR, specifically, for women it

is 3.5% and for men it is 2.0%. When these figures are compared at the national

level, they are higher, since in female adolescents (10 and 19 years old) it is

1.9% and for men of that age it is 0.8% (Gutiérrez et al., 2012). On the

contrary, they are lower compared to those of a study in which 22 states of the

Mexican Republic were included, since they reported an average prevalence of

CAR of 10.5% (Unikel-Santoncini et al., 2010). Specifically, studies on CAR in

high school students belonging to the State of Hidalgo, different prevalence

have been reported: 9.0% (Saucedo-Molina & Unikel-Santocini, 2010), 6.7%

(Unikel-Santoncini et al., 2010), 12.1% (Miranda, 2012), 12.0% (Bernal, Toxqui,

Alvarez, & Vega, 2018).

When

analyzing the trends in the presence of CAR, it can be observed that at the

national level the percentages of CAR are increasing. However, specifically, in

the State of Hidalgo the trend is variable. One possible explanation is that

the evaluation has been carried out with different evaluation instruments

(Ortega et al., 2015). But in any case, the current percentage of CAR, represents an alert, so it is imperative

to develop intervention programs in this population to contribute to their

mental health. Regarding gender, it has been proposed that the percentage of

men who practice CAR is increasing (Radilla et al., 2015); In the present

study, it was found that males represent 57% (4 of 7 participants) of the

students who passed the CP of the EAT, therefore, they are at risk of

developing an eating disorder, in this way it is evidenced that the CARs are

not a women's issue, but also men are affected.

On the other

hand, the type of social ability found in this research draws attention because

most adolescents tend to exercise aggressive behavioral styles, a fact that

coincides with what was recently reported in a study carried out with high

school students (González, Guevara, Jiménez, & Alcázar, 2018). This data

indicates the presence of social incompetence among early or middle

adolescents, this situation is especially important, because this type of non-assertive

behavior can be a risk factor for the physical, mental and social health of

this population, being able to lead to more complex alterations to your care.

It has been proposed that aggressive social behaviors are often accompanied by

physical and psychological violence, as well as intentionally causing conflicts

that can lead to physical aggression, therefore, adolescents with this type of

non-assertive (aggressive) behavior are not only at risk themselves, but also

those around them for being victims of aggression, due to that they spend a

good part of their life in the educational institution living with their peers

(Carrasco & González, 2006). In this regard, the United Nations Children's

Fund (UNICEF, for its acronym in English; 2017), has suggested that the

violence figures are alarming and that they are becoming more common, so that

society in general must play a central role for its eradication, therefore,

these data are a call to develop preventive programs at the primary and

secondary level. Adolescents with this type of non-assertive (aggressive)

behavior are not only at risk themselves, but also those around them for being

victims of aggression, because they spend a good part of their lives in the

educational institution living with their peers (Carrasco & González,

2006). In this regard, the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF, for its

acronym in English; 2017), has suggested that the violence figures are alarming

and that they are becoming more common, so that society in general must play a

central role for its eradication, therefore, these data are a call to develop

preventive programs at the primary and secondary level. Adolescents with this

type of non-assertive (aggressive) behavior are not only at risk themselves,

but also those around them for being victims of aggression, because they spend

a good part of their lives in the educational institution living with their

peers (Carrasco & González, 2006). In this regard, the United Nations

Children's Fund (UNICEF, for its acronym in English; 2017), has suggested that

the violence figures are alarming and that they are becoming more common, so

that society in general must play a central role for its eradication,

therefore, these data are a call to develop preventive programs at the primary

and secondary level. because they spend a good part of their life in the

educational institution living with their peers (Carrasco & González,

2006). In this regard, the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF, for its

acronym in English; 2017), has suggested that the violence figures are alarming

and that they are becoming more common, so that society in general must play a

central role for its eradication, therefore, these data are a call to develop

preventive programs at the primary and secondary level.

However,

passive-style social ability also deserves attention, since students with this

type of behavior are potentially susceptible to being attacked (Vargas, 2018);

The data from this study indicate that just under a quarter of high school

students do not express their opinions or needs, generating interpersonal

conflicts, therefore, they are at risk for their physical and psychological

health; In this regard, there is evidence that inadequate social ability can be

improved with an intervention program (Corrales et al., 2017). On the other

hand, it is important to note that one fifth of adolescents possess the social

ability of assertive type, this represents a protective factor for the

psychological well-being of this population because this style generates well-being,

sense of control and greater likelihood of solving personal problems (Prieto,

2011; Van der Hofstandt, 2005).

Clinically

interesting findings derived from this study is the fact that all students who

passed the CP of EAT-26 (presence of CAR) have an aggressive social ability,

even with extreme scores (99), in this regard, it has been It has been reported

that patients with ED have greater aggressiveness compared to people without

the disorder (Zalar, Weber, & Senec, 2011). Therefore, a timely approach is

required among adolescents, both from CAR and to develop or maintain healthier

HHSS.

Regarding

parenting practices, male high school adolescents perceive greater parental

imposition (imposition of beliefs and behaviors) and less maternal communication,

while women perceive greater psychological control (induction of guilt and

excessive criticism). It was recently reported that the greater the

psychological and behavioral control of the father or the mother, the greater

the behavioral problems with male or female partners (Méndez, Peñaloza, García,

Jaenes, & Velázquez, 2019). The psychological control perceived by

adolescents allows us to understand that the mother has a greater influence on

a cognitive and behavioral level, culturally it can be explained because the

mother spends more time with her children even when she also works outside the

home (Hernández & Lara, 2015 ).

Regarding sex,

the results of the present study are in line with that reported by

Ruvalcava-Romero et al. (2016) and Méndez et al. (2019) because they documented

that male adolescents perceive worse communication. In general, it has been

stated that parental practice based on adequate two-way communication, as well

as adequate autonomy and control, contributes to the health of adolescents and

prevents criminal behavior (Keijsers, 2015).

Now, regarding

the association between the study variables. Specifically, the positive

association between CAR (diet, binge-purge, and oral control) and social

ability in women (that is, the higher CAR, the higher the CABS [aggressiveness]

scores). Biology has explained that people who who practice CAR or those who

have ED, have high levels of Cortisol so they tend to aggressiveness (Warren,

20011) and recently, a positive relationship between this hormone and

aggressiveness has been found (Azurmendi et al., 2016; Pacheco, 2017).

Considering the psychological aspect, it has been found that people who carry

out CAR tend to have greater difficulty in emotional management and

socialization, which is why aggressiveness can be reflected with themselves and

with other people (Cruz-Sáez, Pascual, Extebarría, & Echeburúa, 2013;

Romero et al., 2015). Other researchers reported that 90% of patients with ED

and for obvious reasons with CAR present high scores in the passive or

aggressive dimensions of a personality instrument (Guillament & Canals,

2007). In this study, an association of greater magnitude was observed between

aggressive style and bulimia and to a lesser degree with diet, so these data

add to the postulate that aggressive behavior has a differential behavior for

restriction or for disinhibition (binge eating), these data coincide with what

was found by (Mioto, Pollini, Restaneo, Favaretto, & Preti, 2008).

Furthermore, it is known that in patients with ED, aggressiveness potentiates

or perpetuates eating psychopathology, while, assertive social behavior is a

significant predictor of short and long-term recovery from these disorders

(Behar, 2010). However, this is an open field to delve into populations with

CAR, TCA and their controls.

With regard to

the association between CAR and the perception of parental practices, the

results are consistent with some studies where it is reported that those

parents with little affection can lead to the adolescent having certain

mismatches that direct them to unhealthy behaviors, for example, CAR or the

development of an TCA (Marmo, 2014). This study yielded interesting findings

regarding psychological aspects of non-clinical adolescents, for example,

recently Losada and Charro (2018) reported that in a clinical sample of

patients with ACT, the restrictive diet in anorexia nervosa is linked to a

permissive parental style, while disinhibition (binge) in bulimia nervosa is

associated with an authoritarian parental style, the data found in this study, partially support this stance, because it

was shown that greater maternal imposition, increased dietary restriction,

increased presence of bulimic behaviors (binge-purging) and oral control

(calorie count). <br>In either

case (diet or binge), the family must provide its members with the resources

necessary for their personal, social and well-being development in general, so

that this social institution is a protective factor in adolescence, so it is

necessary to develop timely interventions from the psychology of health

directed towards parents. With regard to non-assertive (aggressive) behavior in

women, it is associated with maternal communication, autonomy, imposition,

psychological and behavioral control, In this way, it is observed that there are differential perceptions

according to sex, but emphasizes that in men the association between aggressive

behavior and maternal psychological control is less compared to women.

Conclusions

CARs are

altered eating patterns and empirical evidence reveals that almost a tenth of

high school students practice them frequently, thus, the importance of their

evaluation and timely detection lies in the fact that they are precursors to

the development of EDs and although, to a greater extent, they are observed in

women, just over half of men also perform them. Likewise, non-assertive

aggressive behavior occurs in more than half of late adolescents, however, 100%

of male and female students who present CAR present such behavior, in addition,

it is associated to a greater extent with the perception of inappropriate

parenting practices of the mother. Therefore, it is suggested to continue

investigating these variables to have a much broader foundation and generate

action plans, firstly, to help reduce the presence of CAR and secondly, to

promote assertive social behavior, the above not only in adolescents, it will

also be pertinent to include younger students and their parents to promote and

develop the behavior also assertive, promoting healthier eating behaviors,

based on the correct execution of parenting practices (communication and

autonomy). The aforementioned is socially relevant, because the next step that

late adolescents will take is to enter the professional level and they will

find themselves in constant situations to make decisions. Timely comprehensive

intervention will help make some of your HHSS more effective. In this way, the

development of interventions for the promotion of health and prevention of the

disease would allow adolescents to respond among their peers and with their

parents more positively, turning their social competences into protective

factors that improve favorable consequences and minimize unfavorable ones,

which will contribute to the physical and psychological well-being of this

population.

Limitations and suggestions for future studies

It should be

noted that the sample of this study was non-probabilistic, which limits the

generalization of the findings. Future studies should include the assessment of

parents in terms of CAR, behavioral styles and their own parental practices in

order to have a completer and more comprehensive overview.

ORCID

Maria Leticia Bautista-Diaz https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1154-1737

Ariana Ibeth Castelán-Olivares https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2758-585X

Armando Martin-Tovar https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1862-4340

Karina Franco-Paredes https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5899-3071

Juan Manuel Mancilla-Diaz https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7259-3667

AUTHORS

'CONTRIBUTION

María Leticia Bautista-Díaz:

Conceptualization, formal analysis, research, supervision, administration of

the project.

Ariana Ibeth Castelán-Olivares:

conceptualization, research, data curation.

Armando Martin-Tovar: methodology,

research, data curation.

Karina Franco-Paredes: Methodology, formal

analysis and visualization.

Juan Manuel Mancilla-Díaz:

Conceptualization, writing-review and editing.

FUNDING

Self-funded

research.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors

declare that there is no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors

thank the authorities of the educational institution for the facilities for the

development of this research and the adolescents for their generous

participation.

REVIEW

PROCESS

This study has been peer-reviewed in a double-blind manner.

DECLARATION

OF DATA AVAILABILITY

The authors of this manuscript are in favor of open science, however,

based on Article 61 of the Code of Ethics of the Psychologist, we store the

database to preserve the identity of the participants and the confidentiality

of the data, but it may be requested to the authors' emails.

DISCLAIMER

The authors are

responsible for all statements made in this article. Neither Interactions nor

the Peruvian Institute of Psychological Orientation are responsible for the

statements made in this document.

REFERENCES

Andrade, P. P. &

Betancourt, O. D. (2010). Evaluación de las

prácticas parentales en padres e hijos. En A. S. Rivera, R. Díaz-Loving, L. I.

Reyes, A. R. Sánchez y M. L. Cruz (Eds.). La

Psicología Social en México XIII, (pp. 137- 143). México: AMEPSO.

Asociación Americana de Psicología (2014). Manual Diagnóstico y Estadístico de los

Trastornos Mentales. México: Editorial Médica Panamericana.

Azurmendi, A., Pascual-Sagastizabal, E.,

Vergara, A. I., Muñoz, J., Braza, P., Carreras, R., Braza, F., &

Sánchez-Martín, J. R. (2016). Developmental trajectories of aggressive behavior in children from ages

8 to 10: The role of sex and hormones. American Journal of

Human Biology, 28,

90-97.

Behar, R. (2010). Funcionamiento psicosocial

en los trastornos de la conducta alimentaria: Ansiedad social, alexitimia y

falta de asertividad. Revista Mexicana de

Trastornos Alimentarios,1, 90-10. Recuperado de http://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/rmta/v1n2/v1n2a1.pdf

Berger, K. (2016). Psicología

del desarrollo. Infancia y adolescencia. España: Médica Panamericana.

Bermúdez, P., Machado, K., & García, I. (2016). Trastorno del

comportamiento alimentario de difícil tratamiento. Caso clínico. Archivos de Pediatría del Uruguay, 87(39),

240-244.

Bernal, G., Toxqui, M. J.G., Álvarez, I., & Vega, A. E.

(Noviembre, 2018). Conductas Alimentarias de Riesgo en Adolescentes. Sesión

cartel presentado en el XVI Coloquio Panamericano de Enfermería, La Habana,

Cuba.

Betina, A. & Contini de González, N. (2011). Las habilidades

sociales en niños y adolescentes. Su importancia en la prevención de trastornos

psicopatológicos. Fundamentos en Humanidades, 13(23), 159-182.

Caballo, V. (2005). Manual

de evaluación y entrenamiento de las habilidades sociales. (6° Edición).

Madrid: Siglo XXI Editores.

Caballo, V.

E., Salazar, I. C., Irurtia, M. J., Olivares, P., & Olivares, J.

(2014). Relación de las habilidades sociales con la ansiedad social y los

estilos/trastornos de la personalidad. Behavioral Psychology /

Psicología Conductual, 22(3), 401-422

Caballo, V.

Salazar, I. S., & Equipo de investigación CISO-A

España. (2018). La autoestima y su relación con la ansiedad social y las

habilidades sociales. Behavioral

Psychology/ Psicología Conductual, 26(1),

23-56.

Campell, K. & Peebles, R. (2014). Eating disorders in children and

adolescents: State of the arte review. Pediatrics, 134(3), 582-592.

Carrasco, M. A. & González, M. J.

(2006). Aspectos conceptuales de la agresión: definición y modelos

explicativos. Acción Psicológica, 4(2),

7-38. Recuperado de https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/3440/344030758001.pdf

Castrillón, I. & Giraldo, O. (2014).

Prácticas de alimentación de los padres y conductas alimentarias en niños:

¿existe información suficiente para el abordaje de los problemas de

alimentación? Revista de Psicología Universidad de Antioquia, 6(1),

57-74. Recuperado de https://aprendeenlinea.udea.edu.co/revistas/index.php/psicologia/article/view/21617/17804

Contreras, L., Morán, J., Frez H., Lagos, C.,

Marín, M. P., Pinto, M. A., & Suzarte A. (2015). Conductas de control de peso en

mujeres adolescentes dietantes y su relación con insatisfacción corporal y

obsesión por la delgadez. Revista Chilena de

Psiquiatría, 86(2).

Recuperado de http://dx.doi.org/10.10167j.rchipe.2015.04.020

Coolican, H. (2005). Métodos de

investigación en estadística y psicología. México: Manual Moderno.

Corrales, A., Quijano, N. K., & Góngora, E. A. (2017). Empatía, comunicación

asertiva y seguimiento de normas. Un programa para desarrollar habilidades para

la vida. Enseñanza e Investigación en

Psicología, 22(1), 58-65

Cortez, D., Gallegos,

M., Jiménez, T., Martínez, P., Saravia, S., Cruzat-Mandich, C., … Arancibia, M.

(2016). Influencia de factores

socioculturales en la imagen corporal desde la perspectiva de mujeres

adolescentes niñas. Revista Mexicana de

Trastornos Alimentarios, 7, 116-124 Recuperado de http://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/rmta/v7n2/2007-1523-rmta-7-02-00116.pdf

Cruz-Sáez, M.S., Pascual, A., Etxebarria,

I., & Echeburúa, E. (2013). Riesgo de trastorno de la conducta alimentaria,

consumo de sustancias adictivas y dificultades emocionales en chicas

adolescentes. Anales de Psicología, 29(3),

724-733.

De la Peña, V., Hernández,

E., & Rodríguez, F. J. (2003). Comportamiento asertivo y adaptación

social: Adaptación de una escala de comportamiento asertivo (CABS) para

escolares de enseñanza primaria (6-12 años). Revista Electrónica de Metodología Aplicada, 8(2), 11-25.

Espina, A., Ochoa de Alda Martínez,

I., & Ortego, M. A. (2007). Conductas

alimentarias, salud mental y estilos de

crianza en adolescentes de Gipuzkoa. España: Delikatuz.

Fleta, J. & Sarría, A. (2012).

Aspectos psicológicos y fisiológicos de la ingesta de alimentos. Boletín de la Sociedad de Pediatría de

Aragón, la Rioja y Soria, 42, 13-21.

Fondo de la Naciones Unidas para la Infancia (2017). Una situación

habitual. Violencia en la vida de los niños y los adolescentes, Autor.

Recuperado de https://www.unicef.org/publications/files/Violence_in_the_lives_of_children_Key_findings_Sp.pdf

Franco, K., Solorzano, M., Díaz, F., & Hidalgo-Rasmussen, C. (2016). Confiabilidad y

estructura factorial del Test de Actitudes Alimentarias (EAT-26) en mujeres

mexicanas. Revista Mexicana de Psicología

(Número especial), 30-31.

García, J. A., López, J.

C., Jiménez, F., Ramírez, Y., Lino, L., & Reding, A. (2014). Metodología

de la investigación bioestadística y bioinformática en ciencias médicas y de la

salud. México: Mc Graw Hill.

Garner,

D., Olmsted, M. P. Bohr, Y., & Garfinkel,

P. E. (1982). The Eating Attitudes Test: Psychometric features and clinical

correlates. Psychological

Medicine, 12, 871-878.

Gonçalvez, S. F.,

Machado, B. C., & Machado, P. P. P. (2011). O papel dos factores

sociocuturais no desenvolvimento das pertur baçôes do comportamento alimentar:

uma revisâo da literatura. Psicologia

Saúde de Do enças, 12(2), 280-297. Recuperado de http://www.scielo.mec.pt/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1645-00862011000200009

González, C., Guevara, Y., Jiménez, D., &

Alcázar, R. J. (2018). Relación entre asertividad, rendimiento académico y

ansiedad en una muestra de estudiantes mexicanos de secundaria, Acta Colombiana de Psicología, 21(1),

116-127. doi: 10.14718/ACP.2017.21.1.6

González, M., Plasencia, D., Jiménez, S.,

Martín, I., & González, T. (2009). Temas

de nutrición: Nutrición básica. La Habana, Cuba: Editorial Ciencias

Médicas.

Guillament, A. L. & Canals, J. C.

(2007). Perfiles

de personalidad en los trastornos de la conducta alimentaria en pacientes

jóvenes. Anales de Pediatría, 66(29),

219-224.

Gutiérrez, J., Rivera-Dommarco, J.,

Shamah-Levy, T., Villalpaldo-Hernández, S., Franco, A., & Cuevas-Nasu, et

al. (2012). Encuesta Nacional de Salud y

Nutrición 2012: Resultados nacionales. Cuernavaca, México: Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública.

Recuperado de https://ensanut.insp.mx/informes/ENSANUT2012ResultadosNacionales.pdf

Guttman, H. &

Laporte, L. (2002). Alexithymia,

empathy, and psychological. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 43(6), 448-455. doi: /10.1053/comp.2002.35905.

Hernández, M. A. & Lara, B. (2015).

Responsabilidad familiar ¿Es una cuestión de género? Revista de Educación Social, 21, 28-44.

Keijsers,

L. (2015). Parental monitoring and

adolescent problem behaviors: How much do we really know? International

Journal of Behavioral Development 40(3), 1-11. doi:

10.1177/0165025415592515

Lara, M. C. & Silva, A. (2002).

Estandarización de la escala de asertividad de Michelson y

Wood en niños y adolescentes: II (Tesis de Licenciatura).

México: Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo.

León, M. & Vargas, T. (2009).

Validación y estandarización de la Escala de Asertividad de Rathus (R.A.S.) en

una muestra de adultos costarricenses. Revista Costarricense de Psicología,

28 (41-42), 187-207. Recuperado de http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=476748706001

López, C., &

Treasure, J. (2011). Trastornos de la conducta alimentaria en adolescentes:

descripción y manejo. Revista Médica

Clínica Las Condes, 22(1), 85-97. Recuperado de http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S071686401170

3960

Losada, A. V., & Charro, A. (2018). Trastornos de la

conducta alimentaria y estilos parentales. Perspectivas Metodológicas,

21(1) 89-112. Recuperado de https://www.aacademica.org/analia.veronica.losada/28.pdf

Marmo, J. (2014). Estilos parentales y

factores de riesgo asociados a la patología alimentaria. Avances en Psicología, 22(2), 1-14. Recuperado de http://www.unife.edu.pe/publicaciones/revistas/psicologia/2014_2/165_Julieta_Marmo.pdf

Martínez, B. & Pedrón, C (2016). Conceptos básicos en alimentación.

España: Nutricia. Advanced Medical Nutrition.

Martínez, L. C., Vianchá, M. A., Pérez, M. P,

& Avendaño, B. L. (2017). Asociación entre conducta suicida y síntomas de

anorexia y bulimia nerviosa en escolares de Boyac, Colombia. Acta Colombiana de Psicología, 20(2),

178-188.

Matalinares-Calvet, M.L., Díaz-Acosta, A.G., Rivas-Díaz,

L.H., Arenas-Iparraguirre, C.A., Baca-Romero, D., Raymundo-Villalva, O., &

Rodas-Vera, N. (2019). Relación entre estilos parentales disfuncionales,

empatía y variables sociodemográficas en estudiantes de enfermería, medicina

humana y psicología. Acta Colombiana de

Psicología, 22(2), 91-111.

Méndez, M. P., Peñaloza, R., García, M., Jaenes, J. C.; &

Velázquez, H. R. (2019). Divergencias en la percepción de prácticas parentales,

comportamiento positivo y problemáticas entre padres e hijos. Acta

Colombiana de Psicología, 22(2),

194-205.

Michelson, L. & Wood, R. (1982). Development and psychometric properties of

the Children’s Assertive Behaviour Scale. Journal

of Behavioral Assessment, 4, 3-14.

Miotto, P., Pollini,

B., Restaneo, A., Favaretto, T., & Preti, A. (2008). Aggressiveness, anger,

and hostility in eating disorders. Comprehensive

Psychiatry, 49(4), 364-73.

Miranda, V.R. (Octubre/Diciembre, 2012). Trastornos de alimentación en estudiantes de secundaria y

bachillerato en Hidalgo. Gaceta Hidalguense de Investigación en Salud.

Recuperado de http://s-salud.hidalgo.gob.mx/wp-content/Documentos/gaceta/gaceta1.pdf

Musitu, G., Buelga, S., Lila, M., & Cava.

M. J. (2001). Familia y adolescencia. Madrid:

Síntesis.

Naranjo, M. L. (2008). Relaciones

interpersonales adecuadas mediante una comunicación y conducta asertivas. Actualidades

Investigativas en Educación, 8(1), 1-27. Recuperado de http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/447/44780111.pdf

Ngo de la Cruz, J. (2012). Alimentación en otras culturas y dietas no convencionales.

Madrid: Exlibris Ediciones. Recuperado de http://cursosaepap.exlibrisediciones.com/files/49-128-fichero/9%C2%BA%20Curso_Alimentaci%C3%B3n%20en%20otras%20culturas.pdf

Organización Mundial de la

Salud (2019). Adolescentes y salud mental. Autor. Recuperado de https://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/topics/adolescence/mental_health/es/

Ortega-Luyando M, Alvarez-Rayón G, Garner DM,

Amaya-Hernández A, Bautista-Díaz ML., &Mancilla-Díaz JM. (2015). Systematic review

of disordered eating behaviors: Methodological considerations for

epidemiological research. Revista

Mexicana de Trastornos Alimentarios, 6(1),51-63. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmta.2015.06.001.

Pacheco, J. L (2017).

Enfoque criminológico de la conducta agresiva y su etiología hormonal. VOX JURIS, 33(1), 159-165.

Papalia, D. E., Feldman, R. D., &

Martorell, G. (2017). Desarrollo humano.

México: Mc Graw Hill.

Peña, E. & Reild,

L.M. (2015). Las emociones y la conducta alimentaria.

Acta de Investigación Psicológica, 5(3),

2182, 2193.

Prieto, M. A. (Abril, 2011). Empatía,

asertividad y comunicación. Revista

Digital Innovación y Experiencias Educativas, 41, 1-8. Recuperado de https://archivos.csif.es/archivos/andalucia/ensenanza/revistas/csicsif/revista/pdf/Numero_41/MIGUEL_ANGEL_PRIETO_BASCON_02.pdf

Radilla, C.C., Vega, S., Gutiérrez, R., Barquera,

S. Barriguete, J. A., & Coronel, S. (2015). Prevalencia de conductas

alimentarias de riesgo y su asociación con ansiedad y estado nutricio en

adolescentes de escuelas secundarias técnicas del Distrito Federal, México. Revista

Española de Nutrición Comunitaria, 21(1), 15-21.

doi:10.14642/RENC.2015.21.1.5037.

Ramírez, J. M. (2006). Bioquímica de la

agresión. Psicopatología Clínica, legal y

Forense, 6, 43-66.

Ríos, R. R. (2017). Metodología para

la investigación y redacción. España: Servicios académicos

Intercontinentales S.L.

Romero, M., Pérez, J. J., Salazar, A. Ayala,

J. A., Amuedo, M., & Devesa del Valle, S. (2015). La emoción de ira en las

personas con trastorno de la conducta alimentaria. Biblioteca Lascasas, 11(1).

Recuperado de http://www.index-f.com/lascasas/documentos/lc0804.pdf

Ruvalcaba-Romero, N. A., Gallegos-Guajardo,

J., Caballo, V. E., &

Villegas-Guinea, D. (2016). Prácticas parentales e indicadores de salud mental

en adolescentes, Psicología desde el

Caribe, 33(3), 169-236. Recuperado de http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/psdc/v33n3/2011-7485-psdc-33-03-00223.pdf

Sánchez, J. C., Villareal, M. E., & Musitu, G.

(2010). Psicología y desórdenes

alimenticios. Nuevo León: Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León.

Saucedo-Molina, T.J. & Unikel-Santoncini, C. (2010a).

Conductas alimentarias de riesgo, interiorización del ideal estético de delgadez

e índice de masa corporal en estudiantes hidalguenses de preparatoria y

licenciatura de una institución privada. Salud Mental, 33(1),

11-19.

Sociedad Mexicana de Psicología (2010). Código Ético

del Psicólogo. Normas de Cónducta,

resultados de trabajo, relaciones establecidas. México: Trillas

Skemp, K., Elwood, R., & Reineke, D. (2019). Adolescent boys are at risk for body image

dissatisfaction and muscle dysmorphia. Californian Journal of Health

Promotion, 17(1), 61-70.

Unikel, C., Díaz de León, C.,

& Rivera J. A. (2016). Conductas

alimentarias de riesgo y correlatos psicosociales en estudiantes universitarios

de primer ingreso con sobrepeso y obesidad. Salud

Mental, 39(3), 141-148. doi: 10.17711/SM.0185-3325.2016.012

Unikel-Santoncini, C., Nuño-Gutiérrez, B., Celis-de la Rosa, A.,

Saucedo-Molina, T. J., Trujillo Chi Vacuán, E. M., García-Castro, F., &

Trejo-Franco, J. (2010). Conductas

alimentarias de riesgo: prevalencia en estudiantes mexicanas de 15 a 19 años. Revista de Investigación Clínica, 62(5),

424-432. Recuperado de https://www.medigraphic.com/pdfs/revinvcli/nn-2010/nn105g.pdf

Valero, S., Granero, R., &

Sánchez-Carracedo, D. (2019). Frequency of family meals and risk of eating disorders in adolescents in

Spanish and Peru. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 51(1), 48-57.

Van der Hofstandt, R. (2005). El libro de las habilidades de comunicación:

cómo mejorar la comunicación personal (2ª ed.). Madrid: Díaz de Santos.

Vargas, N. G. (2018). Relación entre las prácticas parentales en

las habilidades sociales y autoestima en niños escolarizados. (Tesis de Licenciatura).

Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo, México.

Ventura, A. K. y Birch, L. (2008). Does parenting

affect children’s eating and weight status? International

Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 5(15). Recuperado de https://www.aacademica.org/analia.veronica.losada/28.pdf

Warren,

M. (2011). Endocrine manifestations of eating disorders. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 96(2),

333–343. Recuperado de https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2009-2304

Zalar, B., Weber, U., & Sernec,

K. (2011). Aggression and impulsivity

with impulsive behaviors in patients with purgative anorexia and bulimia

nervosa. Psychiatria

Danubina, 23(1), 27-33.