http://dx.doi.org/10.24016/2020.v6n2.126

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Perceived Social Support in

Transgender People: A Comparative Study with Cisgender People

Apoyo social percibido en personas trans: Un estudio comparativo con

personascisgénero

Nuria

Vázquez López 1 *, María Fernández Rodríguez 2, 3, 4,

Elena García Vega 4 and Patricia Guerra Mora 5

1 Advisory Center for Women of the Mancomunidad

Comarca de la Sidra, Spain.

2 Gender Identity Treatment Unit of the Principality of Asturias (UTIGPA),

Spain.

3 Adult Mental Health Center I "La Magdalena", Health Area III, Avilés, Spain.

4 University of Oviedo, Spain.

5 Isabel I University, Spain.

* Correspondence: nuriavazquezlopez92@gmail.com

Received: April 28, 2020 | Revised:

May 24, 2020 | Accepted: June 14, 2020 | Published Online: June 14,

2020.

CITE IT AS:

Vázquez López, N.,

Fernández Rodríguez, M., García Vega, E., & Guerra Mora, P. (2020). Perceived social

support in trans people: A comparative study with cisgender people. Interacciones,

6(2), e126. http://doi.org/10.24016/2020.v6n2.126

ABSTRACT

Background: Trans people may find themselves in a situation of social

discrimination, reflected in their health and in the lack of scientific

research. The minority stress theory points out the importance of social

support for the stress of sexual or gender minorities. This study aims to

explore social support and its dimensions in this population. Method: 81

people participate, of which 36 are trans and 45 non-trans (cisgender), as a

control group. The Mos Social Support

Survey is applied to measure perceived social support and a questionnaire

with sociodemographic variables. Results: The results show that there

are no differences in the perceived social support between both groups.

However, sociodemographic variables such as having a partner, age, and

employment situation show change for the trans population in some dimensions. Conclusion:

These findings promote future lines of research that expand the knowledge of

these variables in this group.

Keywords: Transsexuality;

social support; gender dysphoria; mental health.

RESUMEN

Introducción: Las personas trans pueden encontrarse

en una situación de discriminación social, reflejada en su salud y en la escasa

investigación científica. La teoría del estrés minoritario señala la

importancia del apoyo social para el estrés de las minorías sexuales o de

género. En este estudio se pretende explorar el apoyo social y sus dimensiones

en esta población. Método: Participan 81 personas, de las cuales 36 son

trans y 45 no trans (cisgénero),

como grupo control. Se aplica The Mos Social Support Survey para medir el apoyo social percibido y un

cuestionario con variables sociodemográficas. Resultados: Los resultados

muestran que no existen diferencias en el apoyo social percibido entre ambos

grupos. Sin embargo, variables sociodemográficas como tener pareja, edad y

situación laboral muestran cambios para la población trans en algunas

dimensiones. Conclusión: Estos hallazgos promueven futuras líneas de

investigación que amplíen el conocimiento de estas variables en este colectivo.

Palabras

clave: Transexualidad; apoyo social; disforia

de género; salud mental.

BACKGROUND

Trans people are those whose gender identity and / or expression does

not match the gender expectations of a normative society. Two traditional

binary poles are differentiated (masculine and feminine), but between the two,

there is a range of gender identities and expressions (transsexual,

transgender, transvestite, non-binary, gender fluid and other gender variants).

People whose identity does not fit with the normative sex / gender

dichotomy may have their physical, mental and sexual health affected, due to

the situation of discrimination in a transphobic culture (Basar,

Gökhan and Karakaya, 2016; Nuttbrok et al., 2010; Trujillo, Perrin, Sutter, Tabaac and Benotsh, 2016). These

difficulties of social adaptation would systematically occur in all areas and

areas of their life, such as education, employment, home and health (Boza and

Nicholson, 2014).

Trans people are more likely to experience rejection, discrimination and

violence than non-trans people. In studies such as that of Lombardi, Wilchins, Presing and Malouf (2001) it is found that 60% of transgender people

have experienced violence or rejection, 26% have suffered some violent incident

and 37% have been economically discriminated against. More than 90% of all

trans people reported experiencing harassment or discrimination, compared to

80% of cisgender women and 63% of cisgender men. Similar results are found in

other comparative studies with a non-transsexual population. Nemoto, Bödeker and Iwamoto

(2011) in a sample of 573 transsexual women with a history of prostitution, it

was found that more than half had been physically assaulted,

In addition, these situations of discrimination, social rejection and

violence can affect the mental health of trans people. Both research and the depathologization movement coincide in pointing to the

oppressive social and family environment as a variable to take into account in

psychological distress (Nuttbrok et al., 2014). It

has been found that trans people show greater psychopathology, have a lower

quality of life and well-being with life than the rest of the population. In

general, the group of Lesbians, Gays, Bisexuals and Transsexuals (LGBT) are

more likely to suffer from a mental health problem, where social support can be

essential as a buffer, especially for young boys and girls (McConell,

2015). However, Claes et al., (2015) point out the importance of studying

transsexual people separately from the collective to differentiate the effects

of discrimination based on sexual orientation. However, there is a high trans

population that does not identify as heterosexual (between 38.4% - 61.9%) and

intersectional discrimination may occur, both due to their gender identity and

sexual orientation, the effects on mental health Boza and Nicholson, 2014).

To explain the consequences on mental health of groups that are socially

minority, the minority stress theory should be highlighted (Meyer, 1995). This

theory has been used for other types of minorities, but it has been found

particularly useful in the trans population (Trujillo et al., 2016). From it,

the perceived experiences, their mental, physical and psychological well-being

in general are related to discrimination, prejudice, vigilance and fears that

they may experience due to the socially minority situation (Meyer, 1995).

Stressors that influence minorities can act on health directly through chronic

stress mechanisms, lead to psychological distress or health-related behaviors

such as substance use or use of health services (Balsam, Molina, Beadnell, Simoni and Walters,

2011). In addition, minority stress can occur at the same time as other types

of daily stressors in the non-minority population, thus adding more stress to

the individual's mental health. It is suggested that a possible buffer against

psychological stress in sexual minorities, such as trans boys and girls, could

be social support (Meyer, 2003).

Social support has been shown to be helpful in coping with stress and

controlling the effects it may have on people's health (Schmitt, Branscombe, Postmes & Garcia,

2014). There is no unanimous agreement when defining social support in the

literature. Social support could be defined as the possibility of receiving

help, comfort, assistance or information from both individuals and groups (Earnshaw, Lang, Lippitt, Jin and Chaudoir, 2015).

Authors such as Sherbourne and Stewart (1991)

studied the influence on health of social support due to its different

dimensions. First, they make a dichotomous distinction between structural

support (number of social relationships and interconnectedness of networks) and

functional support (degree to which these interpersonal relationships serve

certain functions). The support a person perceives would be more important than

the support structure itself (Sherbourne &

Stewart, 1991).

In addition, taking into account the functions of social support, they

differentiate between five categories: emotional, that is, expression of

positive affect, empathy and expression of emotions; informational, referring

to advice, advice, information, guidance or feedback; instrumental, that is,

material aid or assistance; positive social interaction, availability of other

people for leisure and fun activities and; affective, expressions of love and

affection. The importance of the dimensions of social support is highlighted

due to its effects on health and not only what are its sources, or the amount

of support perceived in general (Jensen et al., 2014).

Davey, Bouman, Arcelus

and Meyer (2014) recommend that the study of social support in trans people

explore these dimensions. However, research on trans people is not very

abundant (Ellis and Davis, 2017). On the one hand, significant differences have

been found in the perceived social support of trans people compared to the rest

of the population, being trans people who perceived less support than non-trans

/ cisgender people (Basar et al., 2016; Boza and

Nicholson, 2014; Davey et al., 2014; Tebbe and Moraldi, 2016). Factor and Rothblum

(2008) find similar results, particularly in perceived social support from the

family, which was lower in trans people. Davey et al. (2014) in addition to

significant differences in perceived social support between trans and cisgender

people, find differences between trans and non-trans women. Trans women

reported lower levels of available support than cisgender women. Also, in

comparison with other minorities, such as gays and lesbians, less perceived

social support has been found in trans people (Botcking,

Huang, Robinson and Rosser, 2005).

Regarding differences by gender, research in the general population has

indicated that women use social support to a greater extent than men (Pflum, Testa, Balsam, Godblum & Bongar, 2015). In

the trans population, the results are uneven. If we compare trans men and

women, Claes et al. (2015) find that men perceive more support from their

family than women. Other authors, however, do not find that there are

differences regarding gender (Basar et al., 2016).

Regarding this issue, differences by gender in both the cisgender and the LGB

(lesbian, gay, bisexual) population have related the types of support to gender

stereotypes. Ellis and Davis (2017) point out that there are greater

differences regarding social emotional support due to the association with the

female stereotype, while other types of support such as instrumental, would not

have so many differences according to gender. The association of social support

with the feminine and gender socialization would play a relevant role in the

differences (Pflum et al., 2015).

On the other hand, looking at specific variables that may influence

social support, the literature that has taken trans people into account is

scarce. Meier Sharp, Michonski, Babcock and

Fitzgerald (2013) find that there is a significant relationship between having

a partner and high rates of support, in a sample of 593 trans men. In turn,

having greater support was negatively correlated with depression. In trans

women, Yang et al. (2016) point out an association between casual couples with

higher levels of anxiety in the Chinese population. The issue of affective

relationships in trans people has been questioned regarding its stability due

to possible ruptures or crises in the event of a physical transition. Research shows

that half of the relationships were maintained after the transition process

(Brown, 2010).

Regarding the influence of age on social support, if we generalize to

the LGBT population, we find changes in support with respect to being more or

less young. Snapp, Watson, Russell, Díaz and Ryan (2015) point out that for

young people, friends are more relevant than family since they would provide

concrete support towards their sexuality. Previous literature in the general

population shares the trend for social support, where the perception of it

decreases with age (Jensen et al., 2014).

Therefore, the general objective of this study is to evaluate social

support with its different dimensions in trans people and to make a comparison

with cisgender people. In addition, possible differences in social support and

its dimensions based on sociodemographic variables will be studied.

METHOD

Participants

This is a retrospective case-control study with a cross-sectional

descriptive component. This design allows evaluating perceived social support

as well as the influence of sociodemographic variables in trans and cisgender

people. The total sample consisted of 81 people. The group of trans people is

made up of 36, of which 94.4% (n = 34) are users of the Gender Identity

Treatment Unit of the Principality of Asturias (UTIGPA) selected by consecutive

non-probability sampling and 5 , 6% (n = 2) were recruited through snowball

sampling used to gather information from the control group. Of the trans

sample, 66.6% (n = 24) are trans men and 33.4% (n = 12) are trans women. The

mean age of this sample is 27.25 (SD = 11.36), with a range from 15 to 57

years.

A control group selected by snowball sampling was used, consisting of 45

cisgender (non-trans) people, of which 73.3% (n = 33) are men and 26.7% (n =

12) are women. The mean age for the control group is 27.82 years (SD = 8.59),

with a range between 17 and 60 years. No statistically significant differences

were found regarding age and sex / gender ratio (or gender) between both

groups. The only exclusion criterion used was defining oneself as a trans

person.

Instruments

Two instruments were used: The Mos Social Support Survey by Sherbourne and Stewart (1991) and a questionnaire of

sociodemographic variables.

The Mos Social Support Survey is a short, self-administered instrument

designed for the assessment of social support in a multidimensional way. It

consists of 20 items, the first of which reports the size of the social network

and the following 19 are answered on a Likert-type scale, from 1 (never) to 5

(always). Initially, the authors identified 5 scales in the instrument

(emotional support, informational support, instrumental support, positive

social interaction, and affective support). In subsequent validations, authors

such as Revilla, Luna, Bailón and Medina (2005) find

only 3 factors. In this study, three factors arising from the factor analysis

are taken as reference, which correspond to: Factor 1 “emotional /

informational support” (items 3, 4, 8, 9, 13, 16, 17, 19); Factor 2 “positive

social interaction and affective support” (items 6, 7, 10, 11, 14, 18, 20) and

Factor 3 “instrumental” (items 2, 5, 12, 15). The Bartlett sphericity test

(Bartlett = 1124.5; gl = 171; p = 0.00) and the

Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin coefficient (KMO = 0.885) assumed adequate values. The fit

indices of this model are: X2 / gl = 1.936; p = .00;

CFI = 0.89; NFI = 0.83; GFI = 0.99; AGFI = 0.99; SRMR = 0.0497). In our sample,

Cronbach's alpha reliability for the scale of 0.943 was found; 0.926 for factor

1, 0.890 for factor 2 and 0.853 for factor 3, values similar to other studies

carried out (Londoño et al., 2012; Revilla et al.,

2005). CFI = 0.89; NFI = 0.83; GFI = 0.99; AGFI = 0.99; SRMR = 0.0497). In our

sample, Cronbach's alpha reliability for the scale of 0.943 was found; 0.926

for factor 1, 0.890 for factor 2 and 0.853 for factor 3, values similar to

other studies carried out (Londoño et al., 2012;

Revilla et al., 2005). CFI = 0.89; NFI = 0.83; GFI = 0.99; AGFI = 0.99; SRMR =

0.0497). In our sample, Cronbach's alpha reliability for the scale of 0.943 was

found; 0.926 for factor 1, 0.890 for factor 2 and 0.853 for factor 3, values

similar to other studies carried out (Londoño et

al., 2012; Revilla et al., 2005).

The sociodemographic variables questionnaire collected the following

variables: gender, age, length of stay in the UTIGPA, current partner,

coexistence, nationality, employment status and educational status. With regard

to gender, no person was defined as an alternative gender, so two groups were

differentiated (trans men and women or cisgender). Age was subsequently divided

into two groups: 26 years or younger and older than 26. The current partner

variable was categorized dichotomously: yes or no. Coexistence was divided into

the following categories: family of origin, extended family, couple, alone and

with roommates. Nationality was divided into two dichotomous categories,

Spanish versus foreign. The employment situation was divided into three

categories: active, unemployed / retired / pensioner and student. Finally, the

educational situation variable was grouped into three categories: compulsory

education, high school or equivalent studies, and university education. The

variable length of stay in the UTIGPA for trans people was divided into two

categories: less than a year or more than a year.

Process

Data was collected in person with UTIGPA users. For this, scheduled

consultations with clinical psychology or endocrinology were used.

The control group was selected by snowball sampling. Informed consent

was applied, as well as the two instruments. It was applied mainly on paper (n

= 30) although the application was also facilitated through an online survey,

which was used in 33.3% of cases (n = 15). In this cisgender data collection

procedure, two subjects identify as trans and are included in the case sample

(trans people).

Ethical aspects

National and international ethical standards have been met.

Authorization was obtained from the Research Committee of the Health Service of

the San Agustín de Avilés

University Hospital and the informed consent of the users.

Statistical analysis

For data analysis, the statistical package SPSS version 22.0 and the

Factor 7.00 program were used. In the first place, a factor analysis was carried

out to establish the number of factors. Subsequently, internal consistency

estimates were made for the different scales with Cronbach's alpha. Descriptive

and frequency analyzes were performed for the sociodemographic data for the

sample and the control group. Comparisons of means were made using Student's t

tests for the comparison of social support and its dimensions in the sample and

control group, for various sociodemographic variables, as well as to evaluate

the differences in the size of the social network. Analysis of variance (ANOVA)

with post-hoc tests (Bonferroni) was carried out for the work situation,

coexistence, time in the UTIGPA and training situation. in the different

dimensions of social support and total social support in the sample. The effect

size was calculated using the formula of Cohen (1988).

RESULTS

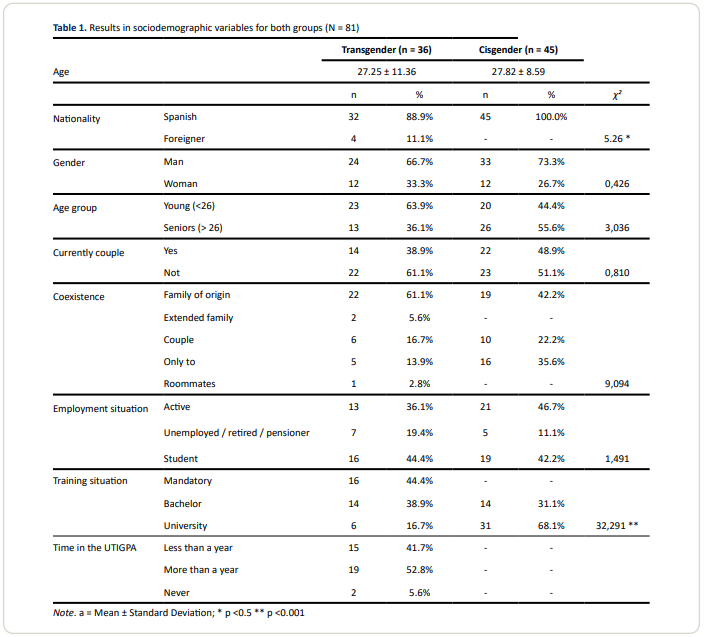

Sociodemographic data for the case and control sample are included in

Table 1.

Statistically significant differences were found in nationality and

educational status. All cisgender people have Spanish nationality, unlike trans

people. Regarding the educational situation, no cisgender person has only

compulsory training and the percentage of people with a university education is

much higher (68.1%) than in transgender people (16.7%).

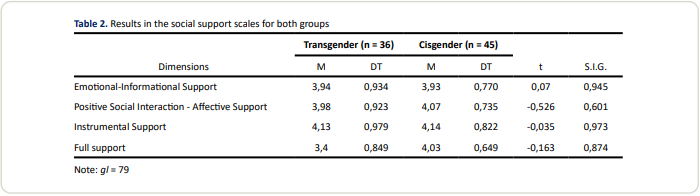

The results found for social support are included in Table 2. No

statistically significant differences were found either in the three dimensions

or in social support considered globally.

Nor are statistically significant differences found in the size of the

social network, that is, in structural social support (t (79) = -. 346; p =

.730), among trans people (M = 7.14; SD = 5.478) and cisgender people (M =

7.51; SD = 4.203). Nor were there significant differences regarding the size of

the social network in cisgender men (M = 6.89; SD = 3.98) and cisgender women

(M: 8.42; SD = 6.27). The different types of social support and total social

support in trans people were analyzed in relation to the sociodemographic

variables.

No differences were found in total social support (t (34.67) = .342; p =

7.34) between trans men (M = 4.034; SD = .675) and trans women (M = 3.97; SD =,

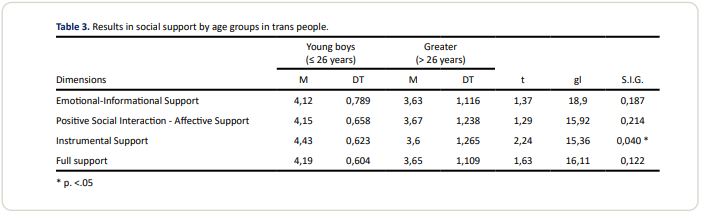

889) or in its dimensions. The results according to age groups are included in

Table 3. Differences were only found in the instrumental support dimension

between young people and those over 26 years of age. The effect size was medium

(r = 0.577). The same t-tests are carried out to check if the results by age

groups also occur in structural social support. No significant differences [t

(16.204) = -. 117; p = .908] were found between the social network of young

people (M = 7.04; SD = 4.13) and older people (M = 7.31; SD = 7.50).

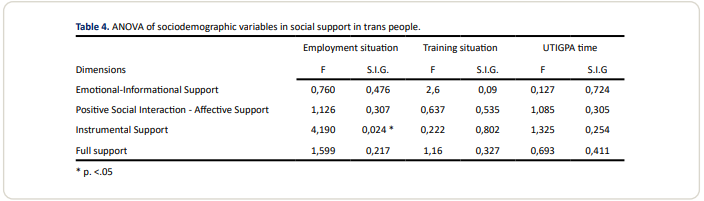

The analyzes of variance for the variables works

situation, training and time spent in the UTIGPA are included in Table 4.

Statistically significant differences were found in

terms of employment status in instrumental social support (F (2) = 4.190; p = .024).

Post-hoc comparisons showed that there were significant differences in

instrumental social support between active people (M = 4.38; SD =. 625) and

unemployed or retired and pensioners (M = 3.25; SD = 1.587); p = 0.34) and

between the unemployed and students (M = 4.312, SD = .6800) with a p = 0.41.

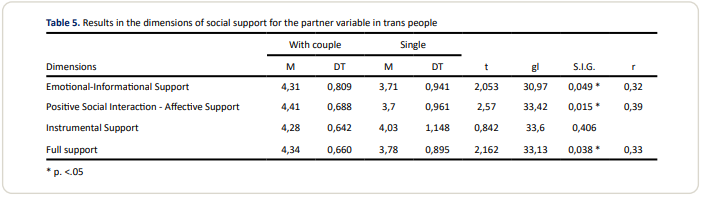

The results for the couple variable are included in Table 5.

Regarding the partner, statistically significant

differences have been found in social support and in several of its dimensions.

Specifically, in emotional-informational support and in positive social

interaction-affective support, both dimensions with a medium effect size.

To know if the statistically significant results are replicated in the

control group, the same tests are performed. No differences were found in

instrumental support by age group of young people (M = 4.22; SD: .595) and

older [M = 4.07, SD = .972; t (40.52) = .658; p = .51]. In the analysis of

variance, no significant differences were found with respect to the employment

situation in instrumental social support [F (2) = 1.36; p = .269] or in total

social support [F (2) = .37; p = .964]. Regarding having or not having a

partner in relation to the dimensions of social support, there are significant

differences in the dimension of positive social interaction-affective support

between people who have a partner (M = 4.30; SD = .697) and people who do not

have a partner (M = 3.85; SD = .715, t (42.98) = 2.157; p = .037). The effect

size in this case is r = 0.30.

DISCUSSION

The first objective of this study was to evaluate social support and its

dimensions in trans people and to make a comparison with the results in

cisgender people. No significant differences were found between the perceived

social support between both groups. The scarce previous literature did establish

differences between social support between trans and cis, where transsexual

people perceived lower levels of social support than the rest of the population

(Basar et al., 2016; Boza and Nicholson, 2014; Davey

et al. , 2014; Tebbe and Moraldi,

2016). Possible explanations for these results could be related to

characteristics of the sample. While in other investigations the surveys of the

broadest and most heterogeneous transsexual population are carried out (Budge,

Adelson and Howard, 2013), the present study is limited, almost entirely, to

people who attend a specific gender identity unit. Trans people who already

have health care probably have greater social support and other living

conditions than those who do not attend (Arcelus, Claes, Witcomb, Marshall and Bouman, 2016). Another possible explanation is that their

perception of support from their environment has increased based on less

discrimination in it. Improvements in visibility have been found in the period

from 2009 to 2012 in countries such as the United States (James et al., 2016).

Also, the fact that there are no differences between the perception of support

between people who attend a specialized unit and cisgender people, could

rethink the supportive role that this type of unit has in trans people.

Another objective was to analyze social support taking into account

different sociodemographic variables. No differences by gender have been found

in this work. Previous studies indicated that there could be differences

between men and women due to differences in gender socialization, the result of

which is that men perceive or have less social support than women (Davey et

al., 2014; Ellis and Davis, 2017). However, the

results of this study do not find differences by gender or in the comparison of

the cisgender population and trans or in the

population of trans people, according to the results of other research (Basar et al., 2016). Regarding other possible

characteristics that could affect social support, no differences have been

found for variables such as coexistence, educational situation and time in the

UTIGPA.

Other sociodemographic variables have shown significant differences in

dimensions of social support. Differences have been found between age groups

(people aged 26 or younger and older than that), having a partner or not, and

by employment status. In the first place, differences taking into account age

are reflected in instrumental social support, that is, in the perception they

have about the availability of material, instrumental or assistance help. In

this study, younger people perceive a greater amount of instrumental social

support than older people, only in the case of the trans population. Previous

literature in the general population shares this trend for social support, where

the perception of it decreases with age (Jensen et al., 2014). This specific

dimension of social support has been studied for populations in situations of

discrimination, but it has not been specifically found in trans people. Studies

of the population with social stigma, such as people with HIV, found that a

greater perception of material or assistance help was associated with a

reduction in stress due to stigma (Earnshaw et al., 2015). Differences have

also been found in instrumental social support depending on the employment

situation. Higher levels of social support have been found in active people

than in unemployed people, and higher in students than in unemployed people.

These differences are not thus found in instrumental social support in cisgender

people, nor are differences found in other types of support. No specific

literature has been found on instrumental social support in transgender people

or how the employment situation or age could affect their perception. Future

research could take these characteristics into account in its studies.

The couple variable has been the one that shows the most differences in

perceived social support in trans people. Higher levels of support have been

found if one has a current partner compared to not having a partner, for two

scales of social support (emotional-informational and positive social

interaction-affective support) as well as for total social support.

Social-emotional-informational support is a factor that includes two types of

emotional support (positive expression of affection, empathic understanding and

expression of emotions) and informative (receiving advice, information and

guidance). The second factor in the questionnaire that shows significant

results is positive social interaction (people for leisure / fun) and affective

support (expression of love and affection). In cisgender people there are only

differences in positive social interaction-affective support, but not in total

social support and emotional-information support, as in trans people. Although

scarce, these results are consistent with previous research. Meier et al.

(2013) also found higher levels of social support in transgender people with a

partner than in single people. The couple has been studied in other sexual

minorities, such as same-sex couples, not so for trans couples (Ellis and

Davis, 2017; Kurdek, 2006). One possible explanation

is that having an affective partner is intrinsically related to these

dimensions of support due to their content.

Taking into account the mental health consequences proposed by the

minority stress theory and how social support can be a buffer against

psychological stress, the results of this research seem encouraging. However,

it is necessary to take into account the diverse results in social support based

on the sociodemographic variables examined in subsequent studies.

Finally, it is worth highlighting the limitations of this research for

the correct interpretation of the results. In the first place, in this study

the sample size is limited due to the difficulties of access to the population

and the conditions of this work itself. In addition, it is a very specific

population of people who attend the services of the UTIGPA. On the other hand,

the trans population is not widely represented or investigated due to its

discrimination situation or other issues in the scientific literature (Factor

and Rothblum, 2007). While other minorities of the

LGBT community, such as gays, lesbians, there are a greater number of

publications (Russell and Fish, 2016), trans people have not been included too

much so far.

As it is an exploratory study and in view of the findings, topics of

interest can be established for further research. It would be convenient to

expand studies on social support for this population group and, in particular,

on its different dimensions. Also delve into characteristics such as age,

partner and employment situation, which in this study have been revealed of

interest. Considering previous findings on the influence of social support on

mental health, it is urged to continue in this line of research.

ORCID

Nuria Vazquez Lopez https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6403-8022

Maria Fernandez Rodriguez https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1123-8220

Elena Garcia Vega https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8754-9949

Patricia

Guerra Mora https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0083-6513

FUNDING

The present study has been self-financed by the

author.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

This study does not present a conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

Arcelus, J., Claes, L., Witcomb,

G., Marshall, E., y Bouman, W. (2016). Risk factors

for non-suicidal self-injury among trans youth. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 13, 402-412.

doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.01.003

Balsam, K., Molina, Y., Beadnell, B., Simoni, J., y Walters, K. (2011). Measuring mutilple minority stress: The LGBT people od color microaggresions scale. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority

Psychology, 17(2), 163-174. doi:10.I037/aO023244

Basar, K., Gökhan, Ö., y Karakaya, J. (2016). Perceived discrimination, social

support, and quality of life in gender dysphoria. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 13(7), 1133-1141. doi: 0.1016/j.jsxm.2016.04.071

Botcking, W., Huang, C., Robinson, B. y Rosser, S. (2005). Are

transgender persons at higher risk for HIV than other sexual minorities? A

comparison of HIV prevalence and risks. International

Journal of Transgenderism, 8(2),

123-131. doi: 10.1300/J485v08n02_11

Boza, C., y Nicholson, K. (2014). Gender-related victimization, perceived social

support, and predictors of depression among transgender Australians. International Journal of Transgenderism, 15,

35-52. doi:10.1080/15532739.2014.890558

Brown., N. (2010). The Sexual

Relationships of Sexual-Minority Women Partnered with Trans Men: A Qualitative

Study. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39, 561-572. doi:

10.1007/s10508-009-9511-9

Budge, S., Adelson, J. L., y

Howard, K. (2013). Anxiety and depression in transgender individuals: The roles

of transition status, loss, social support, and coping. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81(3),

545-557. doi:10.1037/a0031774

Cohen, J. (Ed.). (1988). Statistical power analysis for the

behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Claes, L., Bouman,

W., Witcomb, G., Thurston, M., Fernandez-Aranda, F.,

y Arcelus, J. (2015). Non-suicidal self-injury in

trans people: Associations with psychological symptoms, victimization,

interpersonal functioning, and perceived social support. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 12, 168-179.

doi:10.1111/jsm.12711

Davey, A., Bouman,

W., Arcelus, J., y Meyer, C. (2014). Social support

and psychological well-being in gender dysphoria: A comparison of patients with

matched controls. The Journal of

Sexual Medicine, 11, 2976-2985. doi:10.1111/jsm.12681

Earnshaw, V., Lang, S.,

Lippitt, M., Jin, H. y Chaudoir, S. (2015). HIV

Stigma and Physical Health Symptoms: Do Social Support, Adaptive Coping, and/or

Identity Centrality Act as Resilience Resources? AIDS Behavior, 19(1),

41-49. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0758-3.

Ellis, L. y Davis, M. (2017).

Intimate partner support. A comparasion gay, lesbian

and heterosexual relationships. Personal

Relationships, 24(2), 1-20. doi: 10.1111/pere.12186

Factor, R., y Rothblum, E. (2007). A study of transgender adults and

their non-transgender siblings on demographic characteristics, social support,

and experiences of violence. Journal

of LGBT Health Research, 3(3), 11-30. doi:10.1080/15574090802092879

James, S. E., Herman, J. L.,

Rankin, S., Keisling, M., Mottet,

L., y Anafi, M. (2016). Resumen Ejecutivo del Informe

sobre el 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. Washington,

DC: National Center for Transgender Equality.

Jensen, M., Smith, A.,

Bombardier, C., Yorkston, K., Miró,

J.y Molton, I. (2014).

Social support, depression, and physical disability: Age and diagnostic group

effects. Disability and Health Journal,

7(2), 164-172. doi:

10.1016/j.dhjo.2013.11.001

Kurdek, L. A. (2006). Differences between partners from

heterosexual, gay, and lesbian cohabiting couples. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68,

509-528. doi:

10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00268.x

Lombardi, E., Wilchins, R. A., Priesing, D., y

Malouf, D. (2001). Gender violence: Transgender experiences with violence and

discrimination. Journal of

Homosexuality, 42(1), 89-101. doi:10.1300/J082v42n01_05

Londoño, N., Rogers, H., Filadelfo, J., Posada, S.,

Ochoa, N.L., Jaramillo, M.A., Oliveros, M., Palacio, J.E. y Camilo, D. (2012).

Validación en Colombia del cuestionario MOS de apoyo social. International Journal

of Psychological Research,

5(1), 142-150.

McConnell, E., Birkett, M., y Mustanski, B. (2015). Typologies of social support and

associations with mental health outcomes among LGBT youth. LGBT Health, 2(1),

55-61. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2014.0051

Meier S., Sharp, C., Michonski,J., Babcock, J. y

Fitzgerald, K (2013). Romantic Relationships of Female-to-Male Trans Me: A

Descriptive Study. International Journal

of Transgenderism, 14, 75–85. doi: 10.1080/15532739.2013.791651

Meyer, I. H.

(1995). Minority stress and mental health in gay men. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 36(1), 38-56. doi: 10.2307/2137286.

Meyer, I. H. (2003).

Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual

populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674-697. doi: 10.1037%2F0033-2909.129.5.674

Nemoto, T., Bödeker, B., y

Iwamoto, M. (2011). Social support, exposure to violence and transphobia, and

correlates of depression among male-to-female transgender women with a history

of sex work. American Journal of

Public Health, 101(10), 1980-1988. doi:

10.2105/AJPH.2010.197285

Nuttbrock, L., Hwahng, S., Bockting, W., Rosenblum, A., Mason, M., Macri,

M., y Becker, J. (2010). Psychiatric impact of gender-related abuse across the

life course of male-to-female transgender persons. The Journal of Sex Research,

47(1), 12-23. doi:10.1080/00224490903062258

Pflum, S., Testa, R., Balsam, K., Goldblum, P., y Bongar, B. (2015). Social support, trans community

connectedness, and mental health symptoms among transgender and gender

nonconforming adults. Psychology of

Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 2(3), 281-286.

doi:10.1037/sgd0000122

Revilla. L., Luna, J., Bailón, E. y

Medina, I. (2005). Validación del cuestionario MOS de apoyo social en Atención

Primaria. Medicina de Familia, 6(1),

10-18.

Russell, S. y Fish, J. (2016).

Mental Health in Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Youth. The Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 12,

15.1-15.23. doi:

10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093153

Schmitt, M. T., Branscombe, N. R., Postmes, T., y

Garcia, A. (2014). The consequences of perceived discrimination for

psychological well-being: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 140(4), 921-948.

doi:10.1037/a0035754.

Sherbourne, C.,y

Stewart, A. (1991). The mos social support survey. Social Science & Medicine, 32(6),

705-714. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-B

Snapp, S., Watson, R.,

Russell, S., Díaz, R. y Ryan, C. (2015). Social Support Networks for LGBT Young

Adults: Low Cost Strategies for Positive Adjustment. Family Relations, 64,

420-430. doi: 10.1111/fare.12124

Tebbe, E., y Moraldi, B. (2016).

Suicide risk in trans populations: An application of minority stress theory. Journal of Counseling

Psychology, 63(5), 520-533. doi:10.1037/cou0000152

Trujillo, M., Perrin, P.,

Sutter, M., Tabaac, A., y Benotsch,

E. (2016). The buffering role of social support on the associations among

discrimination, mental health, and suicidality in a transgender sample. International Journal of

Transgenderism, 18(1), 39-52. doi:

10.1080/15532739.2016.1247405

Yang, X., Wang, L., Gu, Y., Song, W., Hao,

C., Zhou, J., Zhang, Q. y Zhao, Q. (2016). A cross-sectional study of

associations between casual partner, friend discrimination, social support and

anxiety symptoms among Chinese transgender women. Journal of Affective Disorders, 203,

22–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.05.051