http://dx.doi.org/10.24016/2020.v6n2.107

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Self-esteem and state-trait

anxiety in Lima's university adults

Autoestima y ansiedad

estado-rasgo en adultos universitarios de Lima

Alejandra Rodrich Zegarra 1*

1

Universidad San

Ignacio de Loyola, Peru.

*

Correspondence: alejandra.rodrich.z@gmail.com

Received: April 26, 2020

| Revised: May 20, 2020 | Accepted: June 10, 2020 | Published

Online: June 13, 2020.

CITE

IT AS:

Rodrich Zegarra, A. (2020). Self-esteem and state-trait anxiety in university

adults from Lima. Interacciones, 6(2), e107. http://doi.org/10.24016/2020.v6n2.107

ABSTRACT

Background: This study sought to determine the

relationship between self-esteem and anxiety in emerging adults from private

universities in Lima. Method: Cross-sectional and correlational in design, it was aimed at determining

the degree or strength of association between self-esteem, state / trait

anxiety in emerging adulthood, for this purpose, the Coopersmith Self-Esteem

Inventory (Form C) and the Anxiety Questionnaire State-Trait (IDARE) were

applied to 221 university students of both sexes, aged between 18 to 25 years. Results: In the hypothesis test, a statistically significant negative correlation

coefficient was obtained between self-esteem and state / trait anxiety, being

the size of the median effect in both cases. Regarding comparisons in

self-esteem and anxiety trait / state according to sex and age, no differences

were found. Conclusion: From the analyzes, it is concluded that there

are an inverse and significant relationship between self-esteem and state /

trait anxiety in emerging adults from Lima.

Keywords: Self-Esteem; State Anxiety; Trait Anxiety.

RESUMEN

Introducción: Este estudio buscó determinar la relación entre la autoestima y la ansiedad

en adultos emergentes de universidades privadas de Lima. Método: De diseño transversal y correlacional, se orientó a determinar el grado o

fuerza de asociación entre la autoestima la ansiedad estado/rasgo en la adultez

emergente, para ello se aplicó el Inventario de Autoestima de Coopersmith

(Forma C) y el Cuestionario de Ansiedad Estado-Rasgo (IDARE) a 221

universitarios de ambos sexos, con edades comprendidas entre 18 a 25 años. Resultados: En el contraste de las hipótesis, se obtuvo un coeficiente de correlación

negativa moderada y estadísticamente significativa entre la autoestima y la

ansiedad estado/rasgo, siendo el tamaño del efecto mediano en ambos casos. Con

respecto a las comparaciones en autoestima, ansiedad rasgo y ansiedad estado

según sexo y edad, no se hallaron diferencias. Conclusión: A partir de los análisis se concluye que existe una relación inversa y

significativa entre la autoestima y la ansiedad estado/rasgo en adultos

emergentes de Lima.

Palabras clave: Autoestima; Ansiedad Estado; Ansiedad Rasgo.

Within the life cycle,

youth is considered one of the stages of human development in which more

changes are experienced, this period, also called emerging adulthood, takes

place between 18 and 25 years, and receives this name because individuals at

this stage they cannot be considered neither adults nor adolescents (Arnett,

2004; Kail and Cavanaugh, 2011). There are economic, academic, social,

intimacy, autonomy and significant decision-making pressures, which are

experienced as overwhelming and could generate anxiety (Riggs and Han, 2009;

Schulenberg, Bryant, and O'Malley).

The World Health

Organization (WHO, 2017) has estimated that more than 260 million people in the

world are affected by this disorder. A recent study reported that the

prevalence of anxiety disorders in adults worldwide ranged between 3.8% and

25%, with important differences depending on the geographical area (Brenes et al., 2005) since, for Anglo-Saxon cultures, the

Rates ranged from 3.8% to 10.4%, while for Hispanic / Latino culture, the

prevalence was 6.2% and 3.2% for Central and Eastern Europe.

In particular, in the

case of Lima, the latest prevalence reports that were made by the Honorio Delgado-Hideyo Noguchi

Mental Health Institute of the Ministry of Health indicated that 10.5% of

adults suffer from anxiety (Honorio Delgado-Hideyo Noguchi Mental Health Institute, 2012).

Taking these data into

account, it can be seen that there is a significant prevalence of this

difficulty in adults in both countries around the world and in Lima, and it is

likely that in the case of emerging adults it will be triggered by all these

regulatory challenges demanded by society due to this, it will be essential to

have a good psychological adjustment, which is related to high self-esteem

(Cameron and Granger, 2018), since this is an important strength to face them.

It should be noted

that, in Peru, the population of people whose ages correspond to emerging

adulthood has increased considerably in recent years because, according to the

National Institute of Informatics and Statistics (INEI, 2016) as of June 30,

2017 it was registered the figure of 8 million 440 thousand 802 people between

15 to 29 years of age, which represents 27% of the total population; and it is

expected that by 2021, this population will amount to 8 million 512 thousand

764 people (INEI, 2017). Thus, the changes that occur in this period and the

increase in this population provide arguments, both at a psychological and

demographic level, for emerging adults to be an important sector of the

population that needs to be studied and cared for,

Self-esteem is defined

by Coopersmith (1981) as the assessment that the individual makes and maintains

with respect to himself, and reveals the extent to which he feels capable,

productive, important and worthy whose dimensions are: personal, social and

family; Research in emerging adult populations suggests that it has a positive

relationship with indicators of good psychological adjustment such as happiness

(Cheng and Furnham, 2004), positive affect (Orth et al., 2012), social skills

and acceptance (Cameron and Granger , 2018). Therefore, this construct has

positive consequences in the internal world (thoughts and perceptions) and

external of an individual (behavior) (Stinson, Logel,

Zanna, Holmes, Cameron, Wood and Spencer, 2008), that

is why, those who have high self-esteem, on average they are happier,

In contrast, low

self-esteem (Pu, Hou & Ma, 2015) is related to indicators of poor mental

health, such as alcohol consumption and depression (Diener et al., 2003).

Therefore, the scientific interest in addressing the development of self-esteem

and its predictive factors, in emerging adulthood, is due to its beneficial

value for psychological health in this period (Hutteman,

Nestler, Wagner, Egloff

& Back, 2015).

Regarding

the difference of

gender in self-esteem, the cross-cultural research of Bleidorn

et al., (2016) with participants from 48 countries, including Peru, found that

men reported higher self-esteem than women, in addition an increase in

self-esteem related to the age from late adolescence to middle adulthood.

Despite these broad cross-cultural similarities, cultures differed

significantly in the magnitude of the effects of gender and age on self-esteem;

These differences were due to variations in the socioeconomic, sociodemographic

and cultural value indicators of each country. Likewise, the meta-analysis by

Zuckerman, Li and Hall (2016) on gender differences in self-esteem (1,148

studies from 2009 to 2013, total N = 1,170,935) found a small effect, favoring

men; also,

While self-esteem is a

factor that contributes to mental health, anxiety is considered to be an

indicator of poor adjustment at this stage, since the authors agree that the

higher the anxiety (trait and state), the lower the ability. adjustment in the

functioning of an individual, (Durand and Cucho,

2015; Kuba, 2017; García, 2014; Medrano, 2017;

Gutiérrez, 2017 and Flores, 2017).

Spielberger and Lushene (1970) distinguish between state anxiety and trait

anxiety, the former being the way in which a person is at a given moment, is

modifiable over time, and is characterized by feelings of tension,

apprehension, uncomfortable thoughts and concerns, along with physiological

changes. Instead, trait anxiety is a stable and consistent predisposition of

behavior, that is, the individual tends to act in a similar way at different

times and in a variety of situations. Both concepts (trait and state) are

interdependent, since people with a high anxiety trait are more predisposed to

present high anxiety states when exposed to anxiogenic stimuli from the

environment. Therefore, physiological factors,

Studies carried out in

Peru in university students related anxiety with psychoeducational and

socio-emotional variables such as academic procrastination (Durand and Cucho, 2015), depression, irrational beliefs (Kuba, 2017 and García, 2014),

burnout (Medrano, 2017), academic performance ( Gutiérrez,

2017), finding that trait and state anxiety are located at moderate and high

levels. Based on the bibliographic review, it has been found that the factors

that could lead to high levels of anxiety in this population are: obtaining

good academic results, adapting to a new social life, establishing bases for

intimacy, living more autonomously and achieving economic independence, (Riggs

and Han, 2009 and Schulenberg, Bryant, and O'Malley, 2004), because according

to Papalia (2010) these development tasks are experienced as stressors for

emerging adults. The latter is one of the most relevant tasks at this stage, as

it provides a sense of satisfaction and value (Papalia, 2010), and to achieve

this it is necessary to be inserted in a labor system, this is evidenced in the

findings of Giannoni (2015 ) in Peru, who reported

that non-working university students had higher anxiety scores compared to

those who did work.

Regarding gender

differences, the literature has shown that women have higher levels of anxiety

than men, so in Peru Giannoni (2015) and Riveros et al. (2007) found that women obtained scores

higher in trait anxiety and college status. In the same way, in Brazil, Benevides and Rodrigues (2010), and in Spain Martínez-Otero (2014) and Balanza

et al., (2009) found significant differences in terms of sex, with higher

levels of anxiety in females with respect to the male in the same population.

In sum, the findings

highlight the importance of self-esteem and anxiety at this stage of

development, however, the nature of the relationship between these two

variables in this age group has not yet been ultimately established, as

demonstrated by the research carried out by Baumeister et al., (2003) in which

it is indicated that both descriptive and correlational studies have yielded

different results regarding the relationship between self-esteem and anxiety,

that is, the magnitudes of the correlations obtained differ between studies in

terms of the correlation coefficient obtained and the respective statistical

significance.

However, in Spain two

experimental studies have been identified, in which it was evidenced that

treatments to improve self-esteem with a cognitive-behavioral approach had the

effect of reducing anxiety in the participants (Narváez,

Rubiños, Cortés-Funes,

Gómez, Raquel and García, 2008 and Cardenal and Díaz Morales, 2000). It should

be noted that, considering other age groups, negative correlations have been

reported between self-esteem and anxiety in children in Peru (Peñaloza, 2015), in adolescents and adults in Spain (Núñez and Crisman, 2016; Núñez, Martín-Albo, Grijalvo and Navarro, 2006) and finally, in adults in

Anglo-Saxon countries (Lee and Hankin, 2009; Riketta, 2004; Watson, Suls and

Haig, 2002).

In conclusion, taking

into account that emerging adulthood is a stage of changes that could cause

anxiety (Papalia, 2010), self-esteem would be considered as a support factor to

face these changes since it is related to a good psychological adjustment.

Likewise, considering that international studies studied the relationship between

self-esteem and anxiety at this stage, they have yielded inconsistent results

(Baumeister, Campbell, Krueger, & Vohs, 2003),

and no antecedents have been identified that relate both constructs in emerging

university adults in Peru.

The main objective of

this research was to determine the relationship between self-esteem and trait

state anxiety with a sample of 221 students between 18 and 25 years old from

private universities in Lima.

METHOD

Design

The present

constitutes an empirical study with quantitative methodology, of the ex post

facto type, since it uses an associative strategy without manipulating

variables to verify the hypothesis raised (Montero & León, 2007).

Participants

The population

consisted of a sample of emerging adults who belong to private universities in

the city of Lima. The selection of the participants was non-probabilistic

(Hernández et al., 2014) and the sample size amounted to 221, a value

calculated through the G * Power 3.1 software (Faul, Erdfelder, Buchner & Lang, 2009), considering a minimal

correlation of .20 according to Cohen (1988), a probability of .05 and a power

of .85.

The sample was made up

of 221 students, however, three cases were excluded because they presented at

least one of the protocols applied incompletely, the analyzes were based on 218

participants among men (n = 90, 41.3.8%) and women. (n = 128, 58.7%) belonging

to three private universities in Lima (Peru). The ages ranged from 18 to 25

years, with the average age being 19 years and 7 months (SD = 1.99).

The inclusion criteria

were students from private universities in Lima between the ages of 18 and 25

who wish to participate in the research. The exclusion criteria were students

from private universities whose nationality is not Peruvian.

Instruments

Coopersmith Self-Esteem Inventory

Instrument created by

Coopersmith (1959) for the quantitative evaluation of self-esteem, being the C

format for adults (16 years and older) the one used in the present

investigation in the version validated by Lachira

(2013). This consists of 25 items to which the subject must respond according

to the identification they have or not with the statement in terms of true

(Like me) or false (Not like me), so each answer is worth one point, and the

total self-esteem score results from the sum of the total of the partial scores

by area.

The reliability of the

original instrument, was found by the test-retest and two halves, ranged

between .78 and .92, being satisfactory (Coopersmith, 1959). In Peru, this

inventory has been used by various authors, thus Tarazona

(2013) reported a Kuder-Richarson 20 coefficient of

.61 and a general Cronbach's Alpha of .79; and Yparraguirre

(2013) obtained a reliability of .605 according to Kuder-Richarson.

Regarding the evidence

of validity of the instrument, Panizo (1985) reported

a correlation of .80 between the original and form C, and a correlation

coefficient between .42 and .66 with self-concept and other self-esteem scales.

Tarazona (2013), evidenced the content validity

relying on the judgment of experts where the concordance index was higher than

.80. Yparraguirre (2013) also submitted the

instrument to the judgment of experts, where the qualifications granted by the

experts were subjected to the binomial test, obtaining a score of .012, therefore,

p <.05 it is established that the agreement between judges is statistically

significant.

State-Trait Anxiety Questionnaire (IDARE)

This questionnaire was

created and validated in Palo Alto, United States, by Spielberger,

Gorsuch and Lushene in 1970,

in order to measure, in a relatively brief and reliable way, anxiety traits and

states. The Spanish version of this inventory was published in 1975 by Spielberger, Martínez, González, Natalicio and Díaz (Spielberger, and Díaz-Guerrero,

1975). For this research, the version validated in the Peruvian context by

Domínguez et al., (2012) will be used.

The IDARE is made up

of 40 items separated into two self-assessment scales to measure state anxiety

and trait anxiety. Each scale has 20 items with a Likert-type response. The

Anxiety-Trait (A / R) scale is scored from 1 to 4 where 1 is not at all and 4

is a lot, while the Anxiety-State scale (A / E) is scored from 1 to 4 where 1

is almost never and 4 is almost always, both scales have inverse items.

In the original

studies, evidence of convergent validity was provided relating the IDARE with

the IPAT Anxiety Scale of Cattell and Scheier (r = .75), and with the Manifest Anxiety Scale-TMAS

of Taylor (r = .80).

Domínguez, Villegas,

Sotelo and Sotelo (2012) conducted a psychometric review of the State-Trait

Anxiety Inventory (IDARE) in a sample of university students from Lima (N =

133), obtaining evidence of validity by internal structure through exploratory

factor analysis ( AFE), reporting a factorial structure that explained 48.61%

and 42.11% of the variance for the Trait Anxiety (RA) and State Anxiety (AE)

scale respectively, with the factor loadings of the items in both cases greater

than. 40. It should be noted that the principal components method, Horn's parallel

analysis and an oblique rotation (Promax) were used for both analyzes. The

instrument presented a structure that reflects the construct to be evaluated

and that is correlated with the literature.

As evidence of

validity in relation to other variables, of the convergent type, Pearson's

correlation coefficients were obtained between the scores of the trait / state

anxiety scales and the state / trait depression inventory, which turned out to

be statistically significant (p <.01), direct and moderate (AE-Euthymia

state r = .698, AE, Euthymia trait r = .383, AE-Euthymia trait r = .618, AE,

Euthymia trait r = .422).

Regarding reliability,

in the original studies in university and pre-university students from the

United States (n = 484) they found an internal consistency by Cronbach's alpha

of .86 for IDARE-R. The test-retest reliability after 104 days was .77. In the

Peruvian context the IDARE has been used by several authors, among them, Arias

(1990) found that the analysis of reliability by the Cronbach coefficient was

.87 for the Anxiety-State scale and .84 for Anxiety- Feature. Likewise, Pardo

(2010) reported a reliability index of alpha coefficients of .806 and .857 with

respect to the Anxiety-Trait scale and State Anxiety, respectively, and the

item-test correlation of all items was adequate. Torrejón

(2011) obtained a Cronbach's alpha reliability of .881 y. 890 for the A-Trait

and A-State scales. In Oliden's research (2013), the

IDARE reached an internal consistency of Cronbach's alpha of .85 for the Anxiety-R

scale, reaching similar values to the previously mentioned study. Domínguez,

et al., (2012) found acceptable reliability indicators through the internal

consistency method, for Anxiety-State a total alpha of .908 was obtained and

for Anxiety-Trait the total alpha was lower, of .874.

Process

The instruments were

applied to university students from Lima belonging to 4 private universities,

for which the researcher presented, through interviews, the project to the

academic authorities of each university. Once the approvals were obtained, it

was coordinated with the administrative staff to carry out the applications

according to the schedule, in the classrooms and at the indicated times.

The instruments were

applied in groups before or after class hours, with the following protocol

being: presentation and information about the objective of the research,

requesting their participation through the signing of the informed consent,

then they proceeded to distribute the sociodemographic record, the Coopersmith

Self-esteem inventory and the State-Trait anxiety questionnaire for each

student.

Data analysis

Once the information

was collected, it was entered into the SPSS-22 Statistical Program (Stadistical Package for Social Sciences), where data

analyzes (descriptive and inferential) were subsequently carried out to reach

conclusions. The normality of the data was determined using the Shapiro-Wilks

(W) statistic, showing that both variables had distributions that did not

approach normality (p> .05), which is why, for the inferential analyzes for

the contrast of the hypotheses were used non-parametric statistics. The

association between the variables was estimated using Spearman's non-parametric

statistic (rs), while the differences of the

variables according to sex were estimated using the Mann Whitney U statistic

(U) and the Kruskal-Wallis was used for the comparison according to age. Once

the aforementioned statistics were obtained, the magnitude of the correlations

was interpreted, the empirical criteria (Hemphill, 2003) derived from a review

of 380 meta-analytical studies were applied instead of the conventional ones by

Cohen (1988). These values include the low level (rs

<.20), moderate (rs <.30) and high (rs> .30). To consider the difference between groups as

significant, the magnitude of rb was taken into

account: <.10 as insignificant; between .10 and .30, low, between .30 and

.50, moderate; and greater than .50, high. The empirical criteria (Hemphill,

2003) derived from a review of 380 meta-analytic studies were applied instead

of the conventional ones of Cohen (1988). These values include the low level

(rs <.20), moderate (rs

<.30) and high (rs> .30). To consider the

difference between groups as significant, the magnitude of rb

was taken into account: <.10 as insignificant; between .10 and .30, low,

between .30 and .50, moderate; and greater than .50, high. The empirical

criteria (Hemphill, 2003) derived from a review of 380 meta-analytic studies

were applied instead of the conventional ones of Cohen (1988). These values

include the low level (rs <.20), moderate (rs <.30) and high (rs>

.30). To consider the difference between groups as significant, the magnitude

of rb was taken into account: <.10 as

insignificant; between .10 and .30, low, between .30 and .50, moderate; and

greater than .50, high. between .30 and .50, moderate; and greater than .50,

high. between .30 and .50, moderate; and greater than .50, high.

Ethical aspects

The researcher

presented, through interviews, the project to the academic authorities of each

university, after obtaining the approvals, the application of the same was

coordinated with the administrative staff and the participation of each student

had the prior consent of each participant through consent. reported for participants

considering the American Psychological Association (APA) standards.

The instruments were

applied in groups before or after class hours, requesting their participation

by signing the informed consent, where the tests are anonymous.

The limitation of this

study is that the results cannot be generalized, since the sample with which we

will work will be a non-probabilistic sample. In addition, the relationship

that will be established between the two constructs will be a correlational

type, but not a causal relationship.

RESULTS

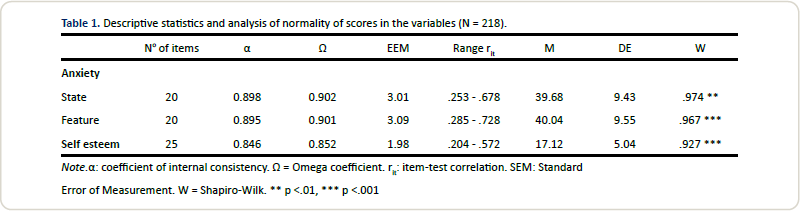

The results of the

analysis of the goodness of fit to the normal curve - carried out using the

Shapiro-Wilk (W) test - indicate that the scores on the self-esteem inventory,

and on the state and trait anxiety questionnaires obtained statistics with

significant values In other words, these variables present a form of

distribution that is not close to normal at the population level (Table 1). It

is due to these results that the inferential analyzes were performed using

non-parametric statistics.

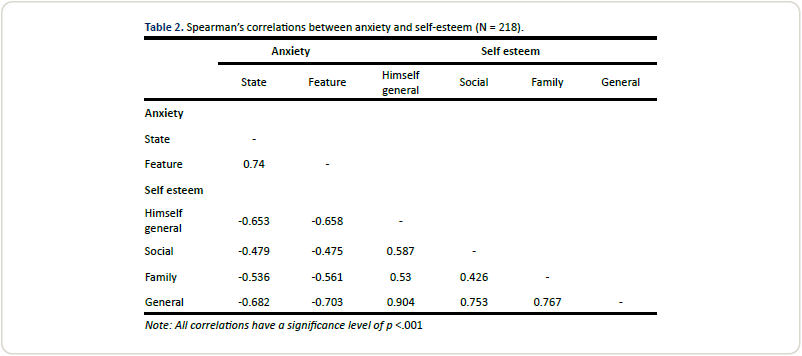

From the analysis, a

moderately negative and statistically significant relationship between

self-esteem and state anxiety was obtained, the effect size being high. It can

also be observed that there is a moderate negative and significant relationship

between self-esteem and trait anxiety (Table 2), with a high effect size.

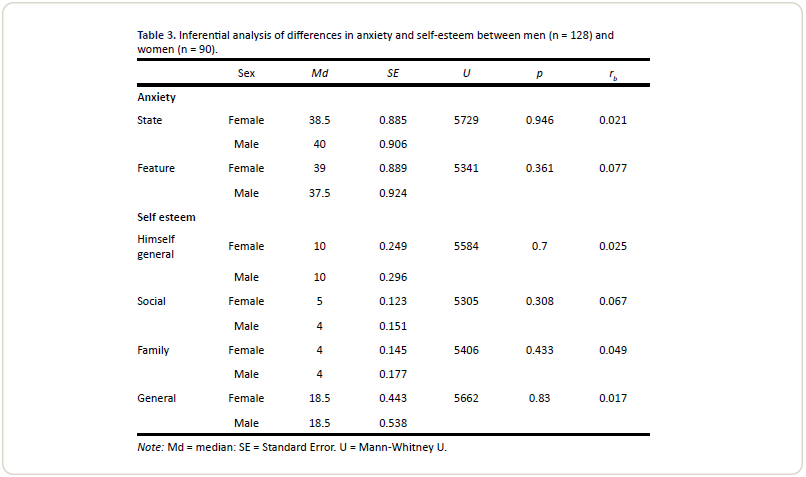

Table 3 shows the

comparisons in the study variables according to sex, finding that there are no

statistically significant differences in self-esteem (areas and global) or in anxiety

(state and trait), obtaining insignificant effect sizes in all contrasts (rb <.10).

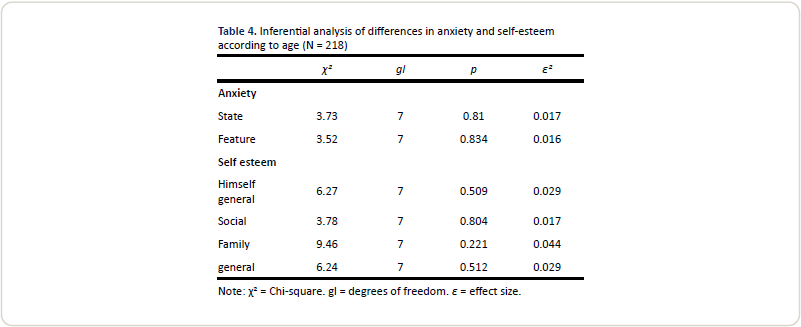

In the analysis

according to the age of the participants, it can be observed in Table 4 that

there are no statistically significant differences in self-esteem, state

anxiety and trait anxiety, with the associated effect sizes being insignificant

(ε² <.10).

DISCUSSION

The main objective of

this research was to determine if there is a relationship between self-esteem,

state anxiety and trait anxiety in emerging adult students from private

universities in Lima, this stage was considered since, according to Arnett

(2004), during it the professional exploration, search for personal identity

and autonomy, aspects that could affect levels of anxiety and self-esteem. From

the main objective, the following objectives were derived: to compare

self-esteem according to sex and age, to compare trait anxiety according to sex

and age, and to compare state anxiety according to sex and age.

When analyzing the

results, it is confirmed that there is a significant negative relationship

between self-esteem and anxiety (state and trait). Regarding this finding,

three explanations are proposed. In the first place, the most categorical

explanation for this relationship is due to the fact that both self-esteem and

anxiety depend on cognitive processes, which is why according to Polaino-Lorente (2010), the first is built with the

representations and cognitions that each person possesses of herself, and these

will interfere with how much or how little she esteems herself. In the same way

it occurs in anxiety, according to Clark and Beck (2012), cognitions or beliefs

exercise an intermediary function between the situation and the emotion, that

is, our way of thinking plays an important influence on how we feel in a

situation, if anxious or serene.

Therefore, our beliefs

and thoughts will have the consequence that self-esteem and anxiety are

affected, due to this McKay (1991) indicates that there are cognitive

distortions that cause the person to selectively base themselves on certain

negative facts of reality, ignoring the rest and causing self-esteem to be

affected, which agrees with Polaino –Lorente (2012), who mentions that a well-founded

self-esteem must be supported by reality. Likewise, it happens with anxiety

since one of the basic principles of cognitive theory is that dysfunctional

beliefs about the threat and errors in cognitive processing produce an

excessive reaction that is incongruous with the reality of the situation,

causing fear excessive (Clark & Beck, 2012).

Second, another

interpretation of the negative relationship between anxiety and self-esteem

found, is suggested by Moreno (2009), he mentions that good self-esteem

develops coping ability, therefore, the higher the self-esteem, the more likely

that the individual perform better coping to adapt to different circumstances,

and present less anxiety, as indicated by Kosic

(2006).

Third, inversely

Moreno (2009) also proposes that people who feel a certain type of anxiety in

certain circumstances perceive themselves as limited in this situation and

could develop low self-esteem, that is, the way a person faces a scenario where

experiencing anxiety will influence your self-esteem.

Due to these three

reasons Oblitas (2004) mentions that there are

interventions with a cognitive approach that address self-esteem, where the

therapist works with the patient's negative thoughts and with the cognitive

distortions that deteriorate self-esteem in order to reduce anxiety, this

remains evidenced in two Spanish experimental studies, in which it was shown

that treatments to improve self-esteem with a cognitive-behavioral approach had

the effect of reducing anxiety in the participants (Narváez,

Rubiños, Cortés-Funes,

Gómez, Raquel and García, 2008 and Cardenal and Díaz Morales, 2000).

In short, it is

highlighted that for emerging adults it will be relevant to have good

self-esteem, since this will be an important basis to face changes generating

less anxiety, since the pressures that are experienced in this stage make it

one of the most critical With respect to the other stages of development, due

to the fact that young people are subjected to vocational and academic

stressors (Fernández, 2009), likewise, social expectations regarding their

economic, labor, family and social responsibility, make up potential stressors

(Darling, McWey, Howard & Olmstead, 2007).

When analyzing the

descriptive results, it was found that there are no significant differences

when comparing the self-esteem scores between women and men, which differs from

what was found by Castañeda (2013), and Milicic and Gorostegui (2011) who

found that women have higher anxiety than males in samples of adolescents and

children respectively, however, it is important to mention that these

populations differ from the present study in the age of the sample. In the same

way, the cross-cultural research of Bleidorn et al.,

(2016) with participants from 48 countries, including Peru, also found that men

reported higher self-esteem than women, however, such a discrepancy may be due

to the fact that in the research of Bleidorn et al.,

(2016) it is also mentioned that countries differed significantly in the

magnitude of gender effects on self-esteem; due to socioeconomic,

sociodemographic and cultural value indicators, in addition, self-esteem was

only measured with a single item.

With regard to

anxiety, the present study also found that there are no significant differences

when comparing the trait anxiety and state anxiety scores between men and

women, this disagrees with what was reported in the background research, since,

in Peru, the studies by Cornejo (2012) and Olivo (2012) concluded that women

present greater anxiety than men between the ages of 18 to 30 and 16 to 18

years respectively, according to each study. Likewise, in the investigations of

Martínez-Otero (2014), in Spain, and Benevides and

Rodrigues (2010), in Brazil, higher anxiety scores were obtained in women than

in men, in a population of adolescents in both studies.

The discrepancies of

the results of this research with the findings of previous studies, in relation

to the fact that there are no significant differences in self-esteem, state

anxiety and trait anxiety between women and men, are due to the fact that the

aforementioned investigations (Martínez- Otero, 2014;

Bleidorn et al., 2016; Cornejo, 2012; Olivo, 2012; and Benevides and

Rodrigues, 2010) were carried out 4 years ago, where women probably still did

not play the roles of today, since according to the INEI (September 2017) to

the year 2016 indicates that the Gender Inequality Index is located at a value

of .391 which reflects that Peru is in a course of decreasing gender

inequality, ranking above 9 Latin American countries such as Colombia and

Brazil.

Therefore, development

tasks such as professional exploration, economic independence and the search

for personal identity (Arnett, 2004), which are some of the goals that could

cause anxiety (Papalia, 2010), and whose fulfillment would lead to a sense of

satisfaction and value (Rice, 1997), are objectives that both men and women

will want to achieve equally at this stage, which is why there are no

differences in the levels of self-esteem and anxiety. On the other hand, one of

the indicators of Gender Equality in Peru is the empowerment of women (INEI,

2017), which favors their self-esteem and, therefore, compared to previous

years, women have more tools to face the adverse situations that arise and

consequently your anxiety levels will be lower.

Finally, it was found

that there are no significant differences in terms of self-esteem, state

anxiety and trait anxiety scores between ages (18-25 years), results similar to

those of Zuckerman et al., (2016) who found that the difference of gender in

terms of self-esteem decreased throughout early and middle adulthood. These results

are based on the fact that, the so-called developmental tasks, which are

changes at both a professional and personal level, that generate a sense of

responsibility that can be overwhelming causing anxiety (Papalia, 2010) and at

the same time, meeting these challenges successfully leads to happiness and

good self-esteem (Rice, 1977) occur within this age range (18-25 years), this

would suggest that, for example, comparing the self-esteem or anxiety between a

young man of 20 with another of 22, there would be no differences since both

are struggling to achieve these tasks imposed by society, which will affect

their self-esteem and anxiety.

On the other hand, it

can be observed that the sample is made up mostly of young people aged 18

(34.7%), 19 (20.3%) and 20 (17.4%) years, therefore there would not be such an

equitable percentage by age for an important comparison. It should be noted

that the research focused on young people between 18 and 25 years of age, which

represents a limitation, since the results could only be generalized for this

age range and only in private universities.

ORCID

Alejandra Rodrich Zegarra https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4497-4697

FINANCING

The present study has

been self-financed by the author.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

This study does not present a conflict of

interest.

REFERENCES

Arnett, J. J. (2004).

Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through the twenties.

New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press

Balanza, S., Morales, I. y

Guerrero, J. (2009). Prevalencia de Ansiedad

y Depresión en una Población de Estudiantes Universitarios: Factores Académicos

y Sociofamiliares Asociados. Clínica y

Salud, 20(2), 177-187.

Baumeister, R. F., Campbell, J. D., Krueger, J. I., & Vohs, K. D. (2003). Does high self-esteem cause better

performance, interpersonal success, happiness, or healthier lifestyles?

Psychological science in the public interest, 4(1), 1-44.

Benevides, A. y

Rodrigues, J. (2010). Ansiedade

dos estudantes diante da

expectativa do exame vestibular. Paideía, 20(45), 57-62.

Bleidorn, W.,

Arslan, R. C., Denissen, J. J., Rentfrow,

P. J., Gebauer, J. E., Potter, J., & Gosling, S.

D. (2016). Age and gender differences in self-esteem—A cross-cultural window. Journal of personality and social psychology,

111(3), 396.

Brenes, G.A., Guralnik, J.M., Williamson, J.D., Fried, L.P., Simpson, C.,

Simonsick, E.M., Penninx,

B.W.J.H., 2005. The influence of anxiety

on the progression of disability. J.Am. Geriatr. Soc. 53, 34–39.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53007.x.

Cameron, J &

Granger, S. (2018). Does Self-Esteem Have an Interpersonal Imprint Beyond

Self-Reports? A Meta-Analysis of Self-Esteem and Objective Interpersonal

Indicators. Personality and Social

Psychology Review, 1–30. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868318756532

Cardenal,

V. y Díaz Morales, J. F. (2000). Modificación de la autoestima y de la ansiedad por la

aplicación de diferentes intervenciones terapéuticas (educación racional

emotiva y relajación) en adolescentes. Ansiedad y

Estrés , 6 (2-3), 295-306.

Castañeda, A. (2013). Autoestima, claridad de autoconcepto y salud mental en adolescentes de

Lima Metropolitana (Tesis de pregrado). Pontificia Universidad Católica del

Perú, Lima.

Cheng, H., & Furnham, A. (2004). Perceived parental

rearing style, self-esteem and self-criticism as predictors of happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 5(1),

1-21.

Clark, D.

y Beck A. (2012). Terapia Cognitiva para los Trastornos

de Ansiedad. Bilbao: Editorial Descleé de Brouwer S.A.

Cohen, J.

(1988). Statistical power analysis for

the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum

Coopersmith,

S. (1981). The antecedents of

Self-Esteem. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists.

Coopersmith, S. (1959). A method for determining types of

self-esteem. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 59, 87-94.

Cornejo, C. (2012). Control psicológico y Ansiedad Rasgo en una muestra clínica de adultos

tempranos. (Tesis de pregrado). Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú,

Lima.

Darling, C, McWey, L, Howard, S. & Olmstead, S. (2007). College student stress: the

influence of interpersonal relationships on sense of coherence. Stress and Health, 23(4), 215-229. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/smi.1139

Diener, E., Oishi, S.,

& Lucas, R. E. (2003). Personality, culture, and subjective well-being:

emotional and cognitive evaluations of life. Annual Review of Psychology, 54(1), 403–425

Domínguez,

S. Villegas, G., Sotelo, N. y Sotelo, L. (2012). Revisión Psicométrica del Inventario de Ansiedad

Estado-Rasgo (IDARE) en una muestra de universitarios de Lima Metropolitana. Revista de Peruana de Psicología y Trabajo

Social, 1(1), 35-45.

Durand, C., y Cucho, N. (2015). Procrastinación académica y ansiedad en

estudiantes de una universidad privada de Lima (Tesis de Licenciatura). Universidad

Peruana Unión.

Endler, N. S. (1997). Stress, anxiety and

coping; the multidimensional interaction model. Canadian Psychology, 38, 136-153.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., Buchner, A., & Lang, A.G.

(2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and

regression analyses.

Fernández, M. (2009). Estrés, estrategias de afrontamiento y

sentido de coherencia (Tesis de Doctoral). Universidad de León, León.

Flores, M. (2017). Los niveles de ansiedad en estudiantes de un

centro preuniversitario del Cercado de Lima (Tesis de Licenciatura).

Universidad Inca Garcilazo de la Vega.

García, S. (2014). Creencias irracionales y ansiedad en

estudiantes de medicina de una Universidad Nacional (Tesis de Maestría).

Universidad San Martin de Porres.

Giannoni, E. (2015). Procastinación crónica

y ansiedad estado-rasgo en una muestra de estudiantes universitarios.

(Tesis de pregrado). Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, Lima.

Gutiérrez, M. (2017). Bienestar psicológico y ansiedad en estudiantes de una Universidad

Nacional del Norte del Perú (Licenciatura). Universidad Privada del Norte.

Hernández, R., Fernández, C. y Baptista (2014). Metodología de la investigación (6ª ed.). México:

McGraw-Hill.

Hutteman, R., Nestler, S., Wagner, J., Egloff,

B., & Back, M. D. (2015). Wherever I may roam: Processes of self-esteem

development from adolescence to emerging adulthood in the context of international

student exchange. Journal of Personality

and Social Psychology, 108(5), 767–783. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000015

Instituto de Salud Mental Honorio Delgado- Hideyo Noguchi. (2012).

Prevalencia y factores asociados de trastornos mentales en la población adulta

en la ciudad de Lima y Callao. LIMA:

Instituto de Salud Mental Honorio Delgado-Hideyo Noguchi.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática (2017). PERÚ:

Brechas de Género 2017.Avances a la igualdad de mujeres y hombres. Recuperado

de https://www.inei.gob.pe/media/MenuRecursivo/publicaciones_digitales/Est/Lib1444/libro.pdf

Kail, R. y Cavanaugh, J. (2011).

Desarrollo humano. Una perspectiva del

ciclo vital. México: CENGAGE Learning.

Kosic, A.

(2006). Personality and individual

factors in acculturation. New

York: Cambridge University Press.

Kuba, C. (2017). Relación

entre creencias irracionales y ansiedad social en estudiantes de la facultad de

psicología de una Universidad Privada de Lima Metropolitana (Tesis de

Licenciatura). Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia.

Lachira, L. (2013). Risoterapia:

intervención de enfermería en el incremento de la autoestima en adultos mayores

del club “Mis Años Felices”. (Tesis de pregrado). Universidad Nacional

Mayor de San Marcos, Lima.

Lee, A.

& Hankin, B. (2009). Insecure Attachment,

Dysfunctional Attitudes, and Low Self-Esteem Predicting Prospective Symptoms of

Depression and Anxiety During Adolescence. Journal

of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 38, 219-231, doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/15374410802698396

Maínez-Otero, V. (noviembre, 2014). Ansiedad en estudiantes

universitarios: estudio de una muestra de alumnos de la facultad de educación. Revista de la Facultad de Educación de

Albacete, 29(2). 63-78.

Medrano, W. (2017). Ansiedad y síndrome de burnout en el personal del área de informática

de una empresa del distrito de Cercado de Lima – 2017 (Tesis de

Licenciatura). Universidad Cesar Vallejo.

McKay, M. (1991). Autoestima:

evaluación y mejora. Barcelona:

Martínez Roca.

Milicic, N. y Gorostegui M. (2011). Género y autoestima: un

análisis de las diferencias por sexo en una muestra de estudiantes de educación

general básica. Psykhe, 2(1). 69-79.

Ministerio de Salud del Perú. (2017). Lineamientos de Política de Promoción de la

Salud en el Perú. Documento técnico. Lima: MINSA.

Ministerio de Salud del Perú. (2017). Modelo de Abordaje para la Promoción de la

Salud. Lima:

MINSA.

Montero,

I., & León, O. (2007). A guide for naming research studies in Psychology. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 7(3), 847-862.

Moreno, P. (2009). Superar

la ansiedad y el miedo: un programa paso a paso (8a ed.). Boston

Descleé de Brouwer.

Narváez, A.; Rubiños,

C.; Cortés-Funes, F.; Gómez, R. y García, A. (2008). Valoración de la

eficacia de una terapia grupal cognitivo-conductual en la imagen

corporal, autoestima, sexualidad y malestar emocional

(ansiedad y depresión) en pacientes de cáncer de mama. Psicooncología , 5(1),

93-102.

Núñez, I. y Crisman, R. (2016). La ansiedad como

variable predictora de la autoestima en adolescentes y su influencia en el

proceso educativo y en la comunicación. Revista

Iberoamericana de Educación. 71(2), 23-45.

Núñez, J., Martín-Albo L., Grijalvo, F.

y Navarro, J. (2006). Relación entre autoconcepto y ansiedad en estudiantes

universitarios. International Journal of Developmental and

Educational Psychology, 1(1), 243-245.

Oblitas, L. A.

(2004). Psicología de la salud y calidad de vida. Mexico: International

Thomson Editores

Oliden, S. (2013). Propiedades

Psicométricas del Test de Orientación Vital Revisado (LOT-R) en un grupo de

universitarios de Lima Metropolitana. (Tesis de pregrado). Pontificia

Universidad Católica del Perú, Lima.

Olivo, D. (2012).

Ansiedad y estilos parentales en un grupo de adolescentes de Lima

Metropolitana. (Tesis de pregrado). Pontificia Universidad Católica del

Perú, Lima.

Orth, U., Robins, R. W., &

Widaman, K. F. (2012). Life-span development of

self-esteem and its effects on important life outcomes. Journal of personality and social psychology, 102(6), 1271.

Papalia,

D. (2010). Desarrollo Humano (11ª

ed.). México D.F.: Mc Graw Hill.

Pardo, F. (2010). Bienestar

psicológico y Ansiedad Rasgo- Estado en alumnos de un MBA de Lima Metropolitana.

(Tesis de pregrado). Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, Lima.

Peñaloza, L. (2015). Ansiedad y autoestima en la niñez intermedia en alumnos de primaria y

secundaria en San Isidro –Lima. (Tesis de pregrado). Universidad Femenina

del Sagrado Corazón, Lima.

Polaino-Lorente, A. (2010). En busca de la autoestima perdida (3a ed.). Bilbao: Descleé de Brouwer.

Pu, J., Hou, H., & Ma, R. (2015). The Mediating Effects

of Self-Esteem and Trait Anxiety Mediate on the Impact of Locus of Control on

Subjective Well-Being. Current Psychology,

36(1), 167–173. doi:

https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-015-9397-8

Rice, P. F. (1997). Desarrollo

Humano: Estudio del ciclo vital.

México: Prentice-Hall Hispanoamericana

Riggs, S. & Han, G.

(2009). Predictors

of Anxiety and Depression in Emerging Adulthood. Journal of Adult Development, 16, 39-52.

Riketta, M. (2004). Does

Social Desirability Inflate the Correlation between Self-Esteem and Anxiety? Sage Journals, 94,

1232-1234. doi:

https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.94.3c.1232-1234

Riveros, M.,

Hernández, H. y Rivera, J. (2007). Niveles

de Depresión y Ansiedad en estudiantes universitarios de Lima Metropolitana. Revista IIPSI, 10 (1), 91-102.

Schulenberg, J. E., Bryant, A. L., & O’Malley,

P. M. (2004). Taking hold of some

kind of life: How developmental tasks relate to trajectories of well-being

during the transition to adulthood. Development and Psychopathology, 16, 1119–1140.

Spielberger,

C.D. y Díaz-Guerrero, R. (1975). IDARE: Inventario de Ansiedad Rasgo-Estado. México: El Manual Moderno.

Spielberger, C. D., Gorsuch, R. L., y Lushene, R. E. (1970). Inventario

de la ansiedad rasgo-estado (IDARE, versión en español del STAI [State Trait – Anxiety

Inventary]: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Sowislo, J. F.,

& Orth, U. (2013). Does low self-esteem predict depression and anxiety? A

meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin, 139(1), 213-240.

doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0028931

Stinson, D. A., Logel, C., Zanna, M. P., Holmes, J. G., Cameron, J. J.,

Wood, J. V., & Spencer, S. J. (2008). The Cost of Lower Self-Esteem:

Testing a Self-and Social-Bonds Model of Health. Journal of personality and social psychology, 94(3), 412-428.

Tarazona, R. (2013). Variables Psicológicas Asociadas al uso de Facebook: Autoestima y

Narcisismo en Universitarios (Tesis de pregrado). Pontificia Universidad

Católica del Perú, Lima.

Torrejón, C. (2011). Ansiedad y Afrontamiento en Universitarios

inmigrantes. (Tesis de pregrado). Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú,

Lima.

Watson, Suls & Haig,

(2002). Global self-esteem in

relation to structural models of personality and affectivity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

83(1),185-197.

Zuckerman,

M., Li, C., & Hall, J.A. (2016). When Men and Women Differ in Self-Esteem

and When They Don’t: A Meta-Analysis, Journal

of Research in Personality, 64, 34-51. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2016.07.007